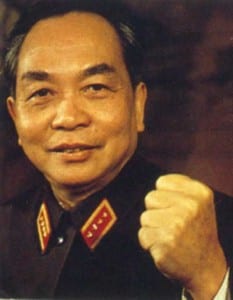

“I want to light a stick of incense to farewell my commander,” said war veteran Chu Van Hoan, one of thousands of mourners of all ages, many in tears, who queued for hours to pay their last respects at an altar inside the Hanoi home of General Vo Nguyen Giap who died on the evening of October 4. ‘Brother Van has left us’, lamented another old soldier using Giap’s wartime alias, in an online posting typical of the flood of sorrowful tributes that swept Vietnamese internet sites following news of his death.

There will be two days of national mourning for Giap who died in a military hospital in Hanoi a month after his 102nd birthday. He will be buried in his native village in the central province of Quang Binh. His long-awaited death – he had been hospitalised since 2009 – marks the passing of the founding generation of Vietnamese communist leaders and confidants of Ho Chi Minh.

Celebrated at home and abroad as a master military strategist, Giap played a key role in formulating a body of military thought centered on the use of a weaker force to defeat a stronger one through a combination of guerilla and regular warfare. He formed the Vietnam People’s Army in 1944 with just 34 recruits and even fewer modern weapons. Within two years he commanded tens of thousands of poorly equipped yet determined fighters ready to resist France’s attempt to reclaim its Indochina empire. Victorious after the eight-year war against the French, Giap remained at the centre of the subsequent 16-year campaign to expel the Americans and reunify the country.

[pullquote]Hugely outclassed in conventional weaponry, and not a professional soldier (he never attended a military academy) Giap, personally, represented among many other things, the superiority of correct political analysis in any conflict, and the role played by a courageous, determined population who understood what was at stake.[/pullquote]Giap’s gained his reputation as a great military leader despite his civilian background. A teacher and journalist, he seems not to have shouldered a weapon until well into his thirties. However victory in Vietnam would require more than feats of arms, Giap and his comrades believed. They were convinced the military outcome would rest on a political and social struggle to transform a feudal economy and society: that empowering the peasantry and overcoming illiteracy must go hand in hand with fighting the French.

Giap was born on August 25, 1911 in a small village in central Vietnam, a dirt-poor region that produced many of the early communist leaders. His parents may have chosen the name Giap, meaning armour, as a talisman; disease had taken their first three children in infancy. Giap’s upbringing was relatively comfortable thanks to his family’s small land holding. His mother was illiterate but his teacher-father introduced him to the Confucian classics and encouraged him to study.

Giap’s early life was a snapshot of the anti-colonial ferment that swept Vietnam from the 1930s. Fluent in French he read Marx, Lenin and a nationalist tract by one Nguyen Ai Quoc, a pseudonym of Ho Chi Minh. The writings of Clausewitz and Napoleon on war also provided inspiration.

Giap was expelled from school for organising a student strike but still managed to gain a degree at the University of Hanoi. He briefly achieved his ambition to become a teacher – an esteemed profession in the Confucian social structure – but writing for radical publications earned him 13 months in jail and ended that career. Though his surname ‘Vo’ translates as ‘martial’ Giap later adopted the nom de guerre of ‘Van’ (literature) reflecting a yearning for his missed civilian vocation.

When Giap got out of prison he married a fellow communist, Nguyen Thi Quang Thai. Only a few months later, on the eve of World War 2 the party leadership ordered him to southern China to link up with the exiled Ho Chi Minh. Giap and Quang Thai never saw one another again. She was arrested by French secret police and died under torture in Hanoi’s Hoa Lo prison (later nicknamed the Hanoi Hilton by US POWs). Their daughter survived and became a leading doctor. The French also executed Giap’s sister-in-law and killed his grandfather by dragging him behind a car.

Giap spent the war years building a resistance base in the mountains and caves of North Vietnam – the launch pad for a nationwide armed revolt. He went on to mastermind the epic 1954 siege and destruction of the French garrison in the valley of Dien Bien Phu. Giap’s peasant army dragged heavy artillery over mountains to surprise and trap French troops. It took 12,000 prisoners, toppled France’s empire in Indochina and inspired anti-colonial movements around the world.

With an independent state in North Vietnam the revolution now had a secure base for the struggle to reunite the country after a century of foreign control and territorial division. President Ho Chi Minh appointed Giap as Defence Minister – a post he held for a quarter century – and chose him as the public face of the party’s 1956 apology for the “excesses” of land reform – including mass executions of landlords and other “class enemies” – though others were directly responsible for the campaign.

Giap’s public appearances in the wake of a backlash over land reform was seen as a move by Ho Chi Minh to direct the spotlight on his protégé preparatory to making him party general secretary, in place of the disgraced Truong Chinh. However the top post eventually passed to a third figure, Le Duan (who may have owed his life to Giap’s wife Quang Thai. Fluent in French, she is said to have interceded with prison authorities and saved Duan from imminent execution).

As Defence Minister Giap was nominally in charge of the 1968 Tet offensive, another battle of global significance. The extent of his control over that campaign remains in dispute, however. Tet ‘68 seems to have been a project of the party’s southern leadership and it is doubtful whether Giap fully supported it. After fierce internal debate it was adopted by Hanoi but main force troops from the north were withheld from most of the fighting.

The spectacular simultaneous attack on more than 100 cities and towns throughout South Vietnam failed in narrow military terms – most captured territory was soon abandoned – but succeeded in its aim of turning US public opinion against the war in an election year. Television covering of marines battling guerillas in the grounds of the American embassy in Saigon exposed the spurious claims of US commanders that they were winning the war and broke the US will to fight.

Giap initiated and oversaw construction and operation of the “Ho Chi Minh Trail” which proved crucial to the struggle for the south. This 3000km network of roads, tracks, fuel pipelines, depots and hospitals was cut through jungle and over mountains. It survived as an unbroken link between northern bases and southern battlefields, via Laos and Cambodia, despite 15 years of incessant bombing.

Official Vietnamese accounts of the war traditionally downplay the roles of individuals – Ho Chi Minh’s excepted. This is in keeping with the party’s customary emphasis on group responsibility (portraits of living leaders are exceedingly rare). While Giap was being lauded as a military genius in the West, the party leadership sought to minimise his contribution to the liberation of the south. This went beyond the need to reinforce a collective ethos.

Having lost his patron with the death of Ho Chi Minh in 1969, Giap fell victim to an internal struggle over power and ideology. Despite his many talents other leaders had superior “class credentials”. Giap had read politics at a French-run university while most of his elite comrades were getting their political education through long stints in French prisons. That this could count against a man who endured years of hardship in the cause while the enemy put to death his closest relatives, speaks volumes about the ferocity of the struggle all were engaged in.

Soon after the liberation of the south, army commander Van Tien Dung, Giap’s deputy at Dien Bien Phu, was given main credit for the 1975 offensive which expelled the Americans. Dung replaced Giap as Defence Minister in 1980 and Giap lost his Political Bureau position soon after, leaving him with the junior job of deputy premier responsible for science and, for a time, family planning. Some low-level party cadres in Hanoi, where I then lived, could not disguise their disappointment and embarrassment at Giap’s humiliation.

Giap apparently argued against a prolonged Vietnamese military presence in Cambodia following Vietnam’s overthrow of the Chinese-backed Khmer Rouge in January 1979. He is believed to have proposed an early withdrawal rather than the 10-year occupation which sapped the already-weakened Vietnamese economy.

In his final years Giap lent his stature as a national hero untainted by scandal to the emerging environmental movement. In 2007 a Hanoi newspaper published the general’s open letter urging the leadership to preserve the old National Assembly building (they went ahead and demolished it). In 2009 Giap called on party leaders to reverse their approval of a proposed bauxite mine in Vietnam’s central highlands. The Political Bureau had sanctioned the project without consulting the increasingly assertive National Assembly. Giap’s letter objected to the Chinese-invested project on environmental and social grounds and reflected broad public opposition to the scheme.

It is most unlikely he was exploited as an unwitting figurehead for these causes. Foreign dignatories who called at Giap’s colonial villa in Hoang Dieu Street – near his former command post and underground bunker in the old citadel of Hanoi – found the then 97-year-old physically frail but still mentally sharp. Drawing on his credentials as an early champion of the environment, Giap’s letter reminded the party leadership he had overseen a study into bauxite mining in the central highlands in the early 1980s. Experts including Soviet scientists had advised Giap against it because of the “risk of serious ecological damage.”

Despite his criticism of the authorities recent official publications have acknowledged Giap’s position in the pantheon of the revolution, calling him one of history’s great generals. He was a key figure in 2005 ceremonies to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the liberation of Saigon, his 100th birthday saw the publication of several books hailing his contributions and a state-funded biopic is in production. Soon Vietnamese streets and parks will carry his name, joining those of other dead commanders who resisted a series of invaders stretching back to antiquity.

Chris Ray is a Sydney-based Asia analyst and journalist. He worked for the Vietnam News Agency in Hanoi from 1976–78.