By Merritt Clifton, Editor in Chief, Animal People

From ANIMAL PEOPLE, January/February 2010 http://www.animalpeoplenews.org/index.html

The struggle for animal defense has been difficult from the start because speciesism cuts deep and is for the most part unquestioned among humans. Also, pro-animal activists have often made serious mistakes, too many times exhibiting a tendency toward disunity instead of collaboration despite common goals. But after more than a century of agitation and work, has there been any progress? In this article, Merritt Clifton, editor of ANIMAL PEOPLE, provides a clear and comprehensive answer to that central question.

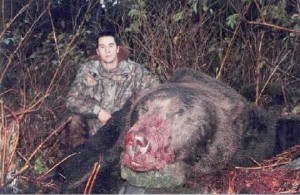

Besides the billions brutalized in factory farming, furs, biomedical, and other forms of exploitation, humans use animals for completely frivolous reasons, as in the depraved "sport hunting".

Comprehensive assessments of progress tend to be fewer–and can be discouraging, in view of frequent contradictory indicators. But the animal cause does not advance primarily through obvious “victories,” or fail through the unmentioned defeats, which most often result when legislation is proposed before sufficient groundwork is done to pass it, or when resources are inadequate to achieve an ambitious goal.

Fundraisers and campaigners like to evoke imagery suggesting that at some point a cause will “triumph,” perhaps after someone blows the right horn to bring all obstacles tumbling down. This is a tried-and-true appeal format, but reality is that if any “war” metaphor is appropriate to advancing the cause of animals, it is that of trench warfare.

We are pushing for change against deeply entrenched industries and cultural traditions, who try to choke every challenge with drifting clouds of poison gas-like propaganda. Quick advances tend to come at immense cost. Abrupt gains are often just as abruptly lost, after opposition mobilizes. For every new activist charging ahead, a veteran reels back in shellshock, having seen entirely too many horrors while experiencing too little progress.

Authentic victories are won by inches, by a process that no “war” metaphor accurately describes. Authentic victories come not through “fighting,” but through persuasion, when sufficient numbers of people who are not directly involved in the cause, and usually not directly involved in resisting it, either, decide to make changes in their lives and their voting patterns. They may decide to have a pet sterilized, stop chaining a dog outside, or–most important–to eat less meat. Or none. They may just quit hunting, or wearing fur, without even thinking much about why.

The choice to make a beneficial change does not come because the people are confronted by rhetorical bayonet charges. Shock tactics may get attention, but to be effective must be followed, immediately, by a positive message that people will internalize and accept, despite having been put on the defensive. Most often the choice of change is made because someone the person making the change knows or admires has already made the same choice, setting a heartening example. A comprehensive review of overall progress in the animal cause, accordingly, is a review of depth of influence.

Where enduring gains have been made, strings of political victories may follow, because public opinion and behavior have already advanced. Legislation, in those instances, codifies what the majority have come to believe. Recent victories of this sort include the reforms of farming practices approved by ballot initiative in California in November 2008, and the simultaneous abolition of greyhound racing in Massachusetts, also by ballot initiative.

Opinion polls indicate that the 2009 European Union ban on imports of seal pelts and byproducts was also such a victory, with broad-based public support throughout most of Europe, but Canada has appealed the ban to the World Trade Organization, contending that the EU had no right under international law to enact it. Should the appeal succeed, the ban would be overturned, and the real test of European opposition to the Atlantic Canadian seal hunt would revert to consumer choice.

Consumer choice can be a misleading indicator, because many of the most abusive industries survive through the participation and patronage of very small minorities: just 4% of Americans hunt, for example. Such industries may have hugely disproportionate political influence, through alliance with other industries, the involvement of well-placed lawmakers, and as a legacy of past popularity. The overwhelming majority of the public may not support the abusive activity, but until they are politically mobilized in opposition to it, as they were in the example of greyhound racing in Massachusetts, the activity will continue through the addiction of the devotees.

The decline of greyhound racing in the U.S. offers some of the most encouraging comparative data from the beginning and end of the past decade: of 50 greyhound tracks operating in 2000, just 23 remain. Declining attendance and an aging clientele point toward the probable demise of the entire U.S. greyhound industry before the end of the new decade.

Greyhound racing may become the first of many forms of animal use in popular entertainment to collapse and disappear. Horse racing and animal use in circuses appear to be following the same trajectory to oblivion, worldwide. Wildlife SOS is cautiously optimistic that the last dancing bear act is off the road in India, and that the last dancing bear has joined hundreds of others at the Wildlife SOS sanctuaries. Rodeo, though still a big business in the U.S., is economically struggling and contracting. Spanish-style bullfighting has just been abolished in Catalonia, which a decade ago still had three of the five most prestigious bull rings in the world. Bullfighting and rodeo promoters continue to try to develop new venues and audiences in China, and elsewhere beyond their traditional bases of support, but with little evidence, so far, of success.

The decline of sport hunting is less obvious, but not less profound. The number of active hunters in the U.S. fell from 13 million in 2000 to about 12.5 million today, not nearly as steep a drop as the attrition of about eight million hunters over the two preceding decades. But most of the casual and occasional hunters dropped out earlier. Now we are down to the most dedicated hunters, most of whom are middle-aged or older, in the age brackets at which hunting participation plummets due to mortality and infirmity. Even very aggressive and well-funded recruitment efforts are not attracting new hunters as rapidly as old hunters die or quit.

Now U.S. sport fishing participation is also down, for the first time over an entire decade in the 70-odd years since the numbers of participants have been tracked–and the 15% drop is proportionately about three times larger than the drop in hunting participation.

The numbers of both hunters and fishers may be expected to continue to fall. With the decline will come a loss of hunter and fisher influence over wildlife policy, especially after opponents of consumptive wildlife use become as politically mobilized as hunters and fishers long have been.

Meat consumption

Hunting and fishing are rationalized by many participants as food-gathering, even though the meat thus obtained costs many times more than meat bought at a supermarket. In truth, hunting and fishing for personal and family consumption account for less than 1% of total U.S. meat production, and make even less of a contribution globally. Despite the importance of hunting and fishing to some small and relatively isolated communities, mostly in climate zones at the extremes of human habitability, hunting and fishing persist almost entirely as blood sports. Global meat production and consumption, unfortunately, have increased even faster than hunting and fishing have declined: from 36 kilograms per person per year in 2000 to 42 in 2009, a rise of 14%. Global meat slaughter has increased 25%, from 42 billion animals killed in 2000 to 56 billion in 2009. Chicken slaughter alone has risen from 13.5 billion to 17 billion, despite the impact on farmers and consumers of the H5N1 avian flu and several other major poultry disease outbreaks.

Yet some encouraging trends lurk among the numbers. Most significantly, U.S. per capita meat consumption has not increased, even as the post-World War II “Baby Boom” generation passed through the age bracket where meat consumption peaked among previous generations. Moreover, per capita meat consumption continues to drop among younger people. Some surveys indicate that up to 18% of U.S. university students are vegetarians or “meat avoiders,” who eat little meat without actually declaring themselves to be vegetarian. Even if this number is three times too high, the percentage of vegetarians among Americans between 18 and 25 appears to be about triple the percentage of vegetarians among their elders.

Similar tendencies are evident in Europe. Meat consumption is actually rising almost entirely in the developing world, especially India and China, among people who have historically been unable to afford to eat as much meat as they wanted, and are now indulging themselves. Dietary disorders once rare in India and China, including obsesity and diabetes, are correspondingly becoming recognized as national problems.

Per capita meat consumption in India is still less than 10% of U.S consumption, and in China is about 40% of U.S. consumption. How long the trend toward increased meat consumption will continue in India, China, and the rest of the developing world is an open question, but the environmental costs of the increase, both globally and locally, are much more apparent today than when U.S. meat consumption spiked upward toward the present rate several decades ago.

The most likely forecast, based strictly on present trends and demographics, is that U.S. and European meat consumption will drop during the next decade, while consumption in the developing world will peak and level out. Global animal slaughter will probably rise to 70 billion before falling–unless climatic, economic, and cultural factors intervene. Rising concern for animal welfare worldwide may change the trends in meat consumption sooner, especially in India and China, where women are enjoying unprecedented political and economic emancipation, and are driving unparalleled growth in pro-animal activity.

Vivisection

There is as yet little antivivisection activism in India, though there has long been some, and is almost none in China. Historically little animal-based biomedical research was done in either nation, and even if much had been done in China, most Chinese people had little way to know about it and no opportunity to protest. This has hugely changed in all respects during the past decade. The rise of strong Indian and Chinese antivivisection movements may follow, but will most likely grow out of pro-animal activism initially organized around other issues. By contrast, public demonstrations of vivisection were among the flashpoints for the rise of organized pro-animal political activity in the western world, more than 200 years ago–along with animal fighting and misuse of working animals.

In the west, laboratory use of animals and animal advocacy have grown approximately parallel to each other ever since. There has never been a time in the history of the U.S. and European biomedical research industries when antivivisectionists were not monitoring their activity and trying to rally opposition to the practices most cruel to animals. Therefore laboratory animal care is relatively strictly regulated in the U.S. and Europe, if not what is done to animals in actual experiments, and U.S. and European researchers have long at least rhetorically accepted the premise that animal use should be reduced, refined, and replaced as much as possible.

The markets for advanced biomedical procedures and pharmaceutical products have rapidly expanded in the newly affluent nations of Asia. Many of these nations already trained scientists who went on to staff laboratories around the world. Now governments interested in keeping their best-educated scientific talent at home are pouring billions of dollars into building their own biotech industries–and are luring western companies to relocate research and developent from the west to Asia.

This has coincided with increasingly violent antivivisection protests in the U.S. and Europe, including arsons, bombings, home invasions, and threats of worse.

The number of nations involved in advanced biomedical research has approximately tripled since 2000. Many of them–like China–have no requirements for public disclosure of information about animal use, little public awareness of animal use in laboratories, young animal advocacy sectors, and restricted though expanding freedom of speech and assembly.

Estimating trends in laboratory animal use, always difficult, has accordingly become more problematic than ever. Working from a variety of sources, including a five-year-old estimate by the British Union Against Vivisection and other numbers wherever available, ANIMAL PEOPLE projects that global use of animals in labs has probably risen from the BUAV figure of about 115 million circa 2000 to nearly 200 million in 2009, with more than half of the total use now occurring in Asia.

British use of animals in labs increased from 2.8 million to 3.7 million during the same years. U.S. lab animal use probably followed the same trend, but since the U.S. does not require laboratories to report use of rats, mice, and birds, there is little way to know for sure. What we do know is that the available data shows several different trends.

U.S. lab use of species other than rats, mice, and birds actually fell from 1,286,412 in 2000 to 1,027,450 in 2007, the latest year for which data has been published. Farm animal use dropped from 159,711 to 109,961. Cat use remained virtually identical, going from 22,755 to 22,687. Dog use increased slightly, from 69,5126 to 72,037. But–though use of chimpanzees in experiments all but stopped–lab use of nonhuman primates jumped from 57,518 to 69,990, reportedly driven by monkey use in bioterrorism research.

The good news, if there is any involving laboratory animals, is that the number of scientific procedures reported in journals has increased at about six times the rate of estimated animal use. Thus the numbers of animals used per experiment are continuing a long downward trend, with progress especially evident in product safety testing.

Dogs & Cats

While laboratory animal use occurs mostly out of sight of the public, dogs and cats live in or near most human homes worldwide, and are so ubiquitous that few people go a day without seeing one or the other. Even feral cats, furtive as they often are, have became widely enough recognized to be mentioned by late-night TV comedians with the expectation that their audiences will know what they are talking about.

The only relatively invisible aspect of the lives and deaths of dogs and cats is what becomes of the 5% or thereabouts who are deemed problematic, or just too numerous, and are delivered to animal shelters in the U.S. and most other developed nations, or are simply poisoned on the streets in much of the developing world.

ANIMAL PEOPLE extensively reviews U.S. animal shelter data every summer, in our July/August edition. Those numbers are less encouraging than we thought they might be by now, a decade ago. Total U.S. shelter killing of dogs and cats has dipped from 4.5 million to 4.2. million, according to our 2009 findings, but the numbers have wobbled up and down within a narrow range throughout the decade.

The only clear indication of progress is that because the U.S. human population has markedly increased, the numbers killed per 1,000 Americans have fallen from 16.6 to 13.5.

Feral cats, typically defined by shelter staff as cats who cannot be handled, ten years ago accounted for 35% of the U.S. shelter death toll. Pit bull terriers accounted for 15%–30% of the dogs. Feral cats are today 43% of the U.S. shelter death toll; pit bulls are 23%, including 58% of the dogs in 2009.

The problem once defined as “pet overpopulation” now has two distinctively different major components.

Feral cats reproduce almost totally beyond any direct human influence. Many feral cats are the offspring of free-roaming or abandoned pet cats, but the pet cat matriarch may have been several cat generations ago. The pet cat sterilization rate has increased from about 70% twenty years ago, nationwide, to 83% today. The pet cat reproduction rate is now well below replacement, with pet cat population replacement and growth occurring in large part through adoptions of feral kittens. This has helped to stabilize feral cat numbers. So has neuter/return, wherever it is conscientiously done.

Nonetheless, further reduction of the feral cat population–and death toll–will require finding more effective ways of sterilizing about three million feral mothers who presently have little or no human contact. A breakthrough may come through the development of affordable and easily deployable non-surgical contraception. Unfortunately, the most promising methods that were in the research and development process a decade ago have not worked in cats. Found Animal Foundation founder Gary K. Michelson, M.D. in October 2008 offered incentives of $75 million to help encourage the discovery and introduction of effective methods of non-surgical dog and cat contraception. This has stimulated scientific effort. What may come of it remains to be seen.

In contrast to feral cats, pit bull terriers are almost entirely purpose-bred. Like the purebred dogs who make up about 15% of shelter intake, according to ANIMAL PEOPLE shelter surveys done in 2008, the overwhelming majority of pit bulls are bred by someone who hopes to profit from selling them. Most pit bulls, like most purebreds who come to shelters, are bought by someone, and flunk out of at least one home before being surrendered or impounded.

Altogether, purpose-bred dogs now make up about 40% of the shelter dog population. Accidental litters are still born, and dogs of unidentifiably mixed ancestry still come to shelters, but they are now a minority in much of the U.S., and may soon become a minority elsewhere. Significantly reducing shelter dog intake will accordingly require significantly reducing intentional breeding.

Strengthened legislation against “puppy mills” has increased impoundments from abusive and negligent breeders more than fourfold, from just over 2,000 in 1999 to nearly 10,000 in 2009. More than 25,000 dogs have been seized from puppy mills just since 2007. This may cut into the volume of badly reared purebreds coming to shelters in the next several years. Pit bulls, however, appear to be coming mainly from backyard breeders, who are far more numerous than puppy millers, and are more difficult to identify.

The only big U.S. cities to have reduced pit bull intakes and shelter killing over the past decade are a few that have either banned pit bulls entirely, like Denver and Miami, or require that they must be sterilized, like San Francisco.

The humane and animal control communities have mostly responded to the pit bull influx by escalating efforts to adopt out pit bulls, after behavioral screening and sometimes after remedial training. In consequence, about 16% of the dogs who were adopted out in 2009 were pit bulls, compared to about 5% of the dogs who were bought from breeders through classified ads. If pit bulls were still killed at the rate they were 10 years ago, the annual toll of a million pit bulls killed in shelters per year would have increased to about 1.3 million.

But whether behavioral screening adequately protects the public from adoptions of dangerous dogs is a question that the courts, adopters, and public opinion are beginning to reconsider. In the first decade that ANIMAL PEOPLE editor Merritt Clifton logged dog attack fatalities and disfigurements, only two shelter dogs made the list. Both were wolf hybrids. None made the list in the next decade. In the past decade, however, 24 U.S. shelter dogs have killed or maimed someone, 16 of them in the past three years and eight in 2009 alone.

The deaths and injuries by shelter dogs were inflicted by 14 pit bulls, two chows, two German shepherds, two Labrador retrievers, a Presa Canario, a Doberman, a Great Dane, and a hound. Nine of the victims were children. These are not huge numbers, but just 27 deaths in 10 years from exploding gasoline tanks destroyed the reputation and sales of the Ford Pinto, once among the most popular cars ever made, promoted and defended by a public relations machine much larger than the animal sheltering community.

Progress in reducing dog attacks in general has gone rapidly backward. Fourteen Americans and Canadians were killed by dogs in 2000; a record 33 in 2007; and 30 in 2009. Pit bulls killed seven of the victims in 2000; a record 22 in 2009. Pit bulls disfigured 40 Americans and Canadians in 2000; 78 in 2009. But Rottweiler attacks have declined, from three deaths and 24 disfigurements in 2000 to four deaths and nine disfigurements in 2009. Rottweiler shelter intake also appears to be coming down, peaking circa 2005.

Dogfighting arrests dropped from 297 in 2000 to 87 in 2009. Fighting dog seizures slipped from 896 to 750.

As there seems to be no indication that dogfighting is actually reduced, and efforts to expose and prosecute dogfighting have intensified since the high-profile arrest of football star Michael Vick in April 2007, the explanation might be that dogfighters are becoming much more sophisticated about evading arrest. The same might be said of cockfighting. 1,508 alleged cockfighters were arrested in 2000; just 656 in 2009.

Yet gamecock seizures barely changed: 7,995 in 2000, 7,917 in 2009.

Abuse & neglect

Strengthened laws and greater public interest in prosecuting animal cruelty and neglect cases have markedly increased the numbers of arrests and convictions resulting from most offenses against animals.

At the rarest extreme, more people have been brought to justice for dragging animals behind cars in each of the past four years, an average of 18 per year, than in the entire decade of the 1990s. More people (22) have been brought to justice for bestiality in 2009 than in the entire decade of the 1980s. At the most common end, animal hoarding convictions, exclusive of puppy mill cases, have nearly doubled in 10 years. But convictions of recognized animal rescuers for neglect are also up 175%, as was discussed more extensively in the November/December 2009 ANIMAL PEOPLE editorial.

Horse neglect and abandonment cases have not increased during the past decade, somewhat surprisingly in view of the amount of media notice focused on alleged horse dumping since the last U.S. horse slaughterhouses closed in 2007. In truth, more horses were impounded due to neglect or abandonment in 1996 (2375) than in any year since, and the numbers since 2007 have remained below 2,000.

But horse slaughter in North America is not reduced. In the year 2000, U.S. slaughterhouses killed 50,449 horses; Canadian slaughterhouses killed 62,000. The Mexican horse slaughter industry was just starting. In 2008, when no horses were slaughtered in the U.S., 77,063 were killed in Canada; 56,731 were killed in Mexico.

Among the pretexts often cited for resuming horse slaughter in the U.S. is the expense of holding increasing numbers of wild horses impounded from leased grazing land by the Bureau of Land Management. An estimated 39,500 wild horses roamed public land in the U.S. west in 2000, while 9,807 horses had been impounded and offered for adoption. Currently, according to the BLM, there are 37,000 wild horses still on the range, and 32,000 in captivity. As obviously unviable as this situation is, the BLM is continuing to capture wild horses at an allegedly unprecedented rate.

Fur & whaling

U.S. retail fur sales, as of 2007, the most recently reported year, came to $1.3 billion, exactly the same as in 2001. This, in inflation-adjusted dollars, meant the fur industry really had not recovered from the crash of 1988-1991, when retail sales bottomed out at $950 million. After two consecutive winters of apparent steep losses, the U.S. retail fur trade may be close to another contraction phase.

But these numbers do not include the use of cheap fur trim on garments, mostly imported from China as byproducts of killing rabbits, dogs, and cats for human consumption. Though importing dog and cat fur into the U.S. and Europe is illegal, detecting it in small amounts is sufficiently difficult to make enforcing the laws difficult.

The rapid rise of animal advocacy within China may significantly reduce consumption of dogs and cats. Meanwhile, encouraging consumer rejection of fur trim remains essential to keeping the fur trade from attracting new customers.

Innumerable issues might appear at a glance to have gone backward abroad, with a second look showing reason for optimism. For example, the self-set Japanese and Norwegian whaling quotas have increased from 560 and 549 in 2000, respectively, to 985 and 885 at present–but neither nation appears to have killed the full quota in either 2008 or 2009.

As a second case in point, the destruction of Zimbabwean wildlife and the Zimbabwean humane sector that began with the land invasions of 2000 has continued. Yet Zimbabwean animal advocates and organizations still exist, and from recent communications, seem optimistic about soon being able to rebuild and resume their work.

History may show that the growth of animal advocacy in the developing world during the first decade of the 21st century was a turning point toward a changed relationship with animals throughout human culture, away from the attitudes which have prevailed since the beginning of agricultural animal husbandry. Among the milestones were that India, Turkey, and Costa Rica adopted national dog sterilization programs; the indigenous Kenyan organizations Youth for Conservation and the Africa Network for Animal Welfare repeatedly rebuffed the well-funded efforts of Safari Club International and others to restart sport hunting, halted in 1977; and the number of active animal advocacy organizations outside the U.S. and Europe appears to have increased at least tenfold.

Among the animal advocacy organizations enjoying the greatest economic growth during the past 10 years, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals more than doubled donation receipts, from $14.5 million to $31.2 milion; the Humane Society of the U.S. also more than doubled donations, from $36.6 million to $87.2 million; PetSmart Charities nearly tripled receipts and disbursements to other animal charities, from $3.5 million to $10 million; the Best Friends Animal Society sextupled donation receipts, from $6.2 million to $37.5 million; and the World Society for the Protection of Animals increased donation receipts sevenfold, from $5.9 million to $44.6 million.

Four of these five organizations, with PetSmart Charities the exception, markedly escalated investment in overseas programs during the decade. PetSmart Charities is not structured to work outside the U.S., but–via ANIMAL PEOPLE and Best Friends–was a significant contributor to relief efforts after the December 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

Barely existing at the beginning of the 21st century, the Animals Asia Foundation is now raising $4 million per year in support of humane work in China, South Korea, and Vietnam. The number of active U.S. affiliates of humane societies in the developing world, as of 2000, could have been counted on one front paw of a six-toed cat. There are now many dozens.

ANIMAL PEOPLE helped to inspire the explosive growth of humane work abroad, by sending free subscriptions to every humane organization; by reporting about overseas issues, beginning before most of the U.S.-based big organizations were much involved abroad; by helping to organize and fund the Asia for Animals and Middle East Network for Animal Welfare conferences; by relaying funds from U.S. donors to foreign animal charities; and by walking many of the foreign animal charities through the steps required to incorporate U.S. affiliates to raise funds for them.

We receive some complaints from readers and donors about allegedly devoting too much page space to international issues, but far more often we hear from readers who are relieved and excited that at last there are open channels enabling them to become directly involved in helping animals in some of the neediest parts of the world.

The stasis of World War I trench warfare ended after help arrived from abroad. Much as we dislike war metaphors, a fast-growing global alliance of animal advocates is enabling the animal cause to challenge entrenched forms of exploitation along a broader front than ever before. Not long ago international networking could be done only by big businesses and governments. Now animal advocates are networking quite routinely across all national and cultural boundaries. Animal use and abuse remain as bloody as ever, but new hope and energy have become as ubiquitous as e-mail.

MERRITT CLIFTON is a veteran journalist specializing in animal issues. He is editor in chief of ANIMAL PEOPLE, the most respected independent monthly devoted to these topics. This article was adapted from the publication’s January-February 2010 editorial.