|

Texas governor Rick Perry has unveiled, with suitable hoopla, his Presidential campaign’s tax plan. His new plan, released last week, differs on the details with the tax plans his rivals for the GOP nod had earlier offered up. But all the plans end up in the same place. They all generate huge tax savings for America’s rich.

A reporter asked candidate Perry if these windfalls for the wealthy — “millions of dollars” in savings for some taxpayers — bothered him at all. Perry shrugged. His response: “I don’t care about that.”

Those of us who do care about “that,” about policies that widen our already staggering economic gaps, now have two new resources. In this week’s Too Much, we review the first, a sprightly UK think tank online pamphlet that offers “ten reasons to care about economic inequality.”

The second, an engaging 17-minute video from the famed epidemiologist Richard Wilkinson, charts how inequality is eating away at how well — and how long — we all live. Rick Perry will likely never watch this video. The rest of us should.

GREED AT A GLANCE

|

America’s most unequal city? That dishonor, the Census Bureau revealed last week, falls to Atlanta. But Atlanta’s movers and shakers don’t appear quite ready to discuss their city’s shameful distinction. The day before the new Census data release, Atlanta city officials cleared out an Occupy Atlanta encampment and arrested dozens of occupiers. Nationally, meanwhile, the Occupy movement seems to be resonating ever more powerfully. By a 43 to 27 percent margin, a new New York Times/CBS News poll shows, Americans agree “with the views of the Occupy Wall Street movement.” Nearly a third of Americans say they still don’t know much about the Occupy movement, as of mid October. But most of these seem potential supporters. By a 66 to 26 percent margin, the new poll data relate, Americans want the nation’s wealth “more evenly distributed.”

Between the Occupy movement and a tottering global financial system, some households of means seem to be feeling a little spooked. The latest sign of their unease: the “paranoia portfolio.” Private bankers worldwide, notes the Swiss bank Wegelin’s Ivan Adamovich, are steering their worried clients into investment portfolios specially “designed to protect people’s wealth in the face of global catastrophe.” Other super rich are rushing to park their spare cash in luxury real estate, mostly in London and Paris, or timeless automobiles. Rolls-Royce last year sold 2,711 vehicles, a record, and this year is looking even better . . .

Bank of America has been making plenty of money lately — $6.2 billion in 2011’s third quarter alone — but precious few friends. So the bank has just launched a charm offensive that has bank execs breaking bread with local community leaders. These local leaders better feel charmed — or else. So suggests BofA CEO Brian Moynihan, who took in $10 million for his labors last year. Bank of America’s critics, Moynihan warned last week, “ought to think a little” about all the “good” the bank does before they ”start yelling at us.” BofA, meanwhile, continues to give America’s 99 percent more to think — and yell — about. Last month, the bank had a huge pile of risky assets shifted from one subsidiary to another, in the process gaining federal deposit insurance that guarantees BofA another bailout, at taxpayer expense, if the assets tank . . . Bank of America has been making plenty of money lately — $6.2 billion in 2011’s third quarter alone — but precious few friends. So the bank has just launched a charm offensive that has bank execs breaking bread with local community leaders. These local leaders better feel charmed — or else. So suggests BofA CEO Brian Moynihan, who took in $10 million for his labors last year. Bank of America’s critics, Moynihan warned last week, “ought to think a little” about all the “good” the bank does before they ”start yelling at us.” BofA, meanwhile, continues to give America’s 99 percent more to think — and yell — about. Last month, the bank had a huge pile of risky assets shifted from one subsidiary to another, in the process gaining federal deposit insurance that guarantees BofA another bailout, at taxpayer expense, if the assets tank . . .

Who decides how much CEOs like Brian Moynihan get to take home every year? Corporate boards of directors have that responsibility — and the directors who sit on them get paid generously for exercising it. In 2009, the annual pay of a typical Fortune 500 corporate director topped $200,000 for the first time. In 2010, the pay consultant firm Towers Watson reported last week, median director pay rose even higher, to $212,500. Not bad for a job that takes up an average 4.3 hours a week, according to a recent National Association of Corporate Directors study. Corporate directors hail largely from the executive suites of other corporations and the ranks of retired CEOs . . .

Sleepless nights can come in bunches when you find yourself having to sell your home for a big loss, as millions of Americans now know first-hand. Larry Ellison, the CEO at Oracle business software, doesn’t have that problem. Ellison has just listed a 6.9-acre home and horse farm he owns in Northern California for $19 million. He paid $23 million for the property in 2005. But Ellison doesn’t figure to miss the $4 million haircut he’s now facing. That loss amounts to around one-hundredth of 1 percent of his $33 billion net worth. Where will Ellison sleep once he unloads his horse farm? Who knows? The Oracle kingpin owns at least 15 homes, including two in Southern California’s Malibu alone. Says Malibu mayor John Sibert: “One or the other of his yachts shows up here about four times a year, right off shore. Other than that, we don’t see him around town very much.”

|

Quote of the Week

“Everything is for the wealthy. This used to be a lovely country, but everything is sliding.”

Jo Waters, an 87-year-old retired hospital administrator from Pleasanton, California, New York Times, October 26, 2011

Stat of the Week

Nearly a century ago, in 1917, America’s top 0.1 percent took home 127 times the average income of the nation’s bottom 90 percent. In 2007, Yale political scientist Jacob Hacker noted last week, the top 0.1 percent took home 220 times the bottom 90 percent’s average income.

Email this Too Much

issue to a friend

|

IN FOCUS

|

Our Tilt to the Top: The Deepest Stats Yet

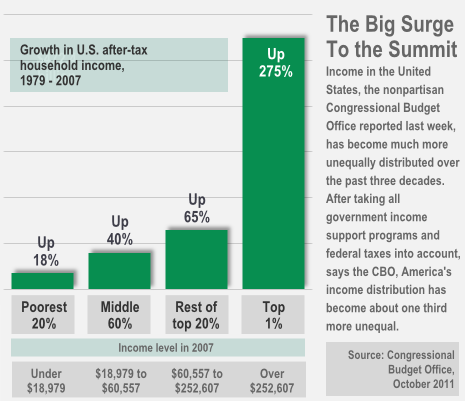

new report — from the buttoned-down number crunchers at the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office. And the portrait they paint essentially gives the Occupy movement’s most basic insight, that our top 1 percent has hijacked the nation, an official government imprimatur.

Over the past three decades, the new CBO study documents, the deep pockets who make up our top 1 percent have more than doubled their share of America’s after-tax income, “from nearly 8 percent in 1979 to 17 percent in 2007.”

What makes the new CBO figures so significant? Other federal agencies, after all, do regularly drop their oars into America’s income distribution waters. But the statistics these agencies report never quite capture the complete big picture.

The Census Bureau’s annual income surveys, for instance, don’t even attempt to cover what’s happening at America’s economic summit. And IRS statistical tallies only include Americans who make enough to have a file a tax return.

Analysts at the Congressional Budget Office neatly solve this statistical snafu. They massage Census and IRS data together. But they don’t stop there. Their new report also directly challenges the nation’s inequality “deniers,” those apologists for concentrated income and wealth who loudly claim that the United States hasn’t become nearly as unequal as the Census and IRS data suggest.

These apologists invoke a variety of objections. Income breakdowns, they insist, should take into account the dollar value of all the government services that go to poor people — and adjust for differences in household size as well. The new CBO report released last week, Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007, does all that and more.

The CBO’s expansive definition of income encompasses nearly every household revenue source imaginable — not just wages and salaries, but income allocated to 401(k) plans, not just Social Security and workers’ comp, but “the value of in-kind benefits,” everything from food stamps to free school lunches.

The CBO even counts as individual income what employers shell out for your Social Security, Medicare, and health insurance coverage. In other words, the CBO essentially tallies everything that impacts your economic well-being.

On top of all this, the CBO has adjusted all its income figures for inflation, for every year from 1979 through 2007. Why pick these two particular years? One practical reason: Some data streams the CBO taps only start in 1979.

The more significant reason: Both 1979 and 2007 rate as “economic peak years just prior to a recession.” By starting and ending at an economic peak, Congressional Budget Office researchers are comparing apples to apples — and giving a much more accurate sense of basic long-term trends.

These trends, the new CBO analysis finds, vary enormously by income level.

For households in the top 1 percent — households making over $352,875 before federal taxes in 2007 — the trend line goes steeply up. These households saw their after-tax incomes soar 275 percent between 1979 and 2007, quadruple the 65 percent increase for the rest of the households in the nation’s top 20 percent.

And below that top 20 percent? After-tax incomes for America’s statistical middle class, the middle 60 percent of the nation’s income distribution, increased “just under 40 percent,” or a bit over 1 percent a year, barely enough to cover an average household’s rising utility bills.

Households in the bottom 20 percent fared even worse. Their incomes, after adding in federal “transfers” like food stamps and subtracting federal taxes, increased only 18 percent over 28 years, less than 1 percent a year.

All this “uneven income growth,” the new CBO report notes, has left the United States with a “substantially more unequal” distribution of income.

The new CBO numbers tell the same inequality story, no matter how you cut the data. Every category of income — from wages and salaries to dividends and capital gains — tilted more to the top 1 percent in 2007 than in 1979.

Has that tilting continued? The new Congressional Budget Office report doesn’t go beyond 2007. But all other signs, from CEO compensation to hedge fund manager pay rankings, point to even greater inequality today.

The latest sign comes courtesy of the Social Security Administration. SSA researchers reported earlier this month that half of America’s workers earned under $26,364 last year. The number of Americans making over $1 million, according to W-2 form payroll data, skyrocketed 18 percent.

|

New Wisdom

on Wealth

Glenn Greenwald, How the Rich Subverted the Legal System and Occupy Wall Street Swept the Land, TomDispatch, October 25, 2011. Inequality has been widening for decades. Why is the Occupy Wall Street movement growing so explosively right now?

Matt Taibibi, OWS’s Beef: Wall Street Isn’t Winning — It’s Cheating, Rolling Stone, October 25, 2011. A classic retort to the claim that Occupy Wall Streeters jealously “envy” the wealthy for their success.

David Cay Johnston, Beyond the 1 percent, Reuters, October 25, 2011. Inside the top 1 percent, the top 0.1 percent pay the lowest tax rates.

Sarah Anderson, The Costs of Wall Street Greed, The Nation, October 26, 2011. A look at how much the financial industry is costing average Americans on a monthly basis.

Kevin Drum, The Price of Plutocracy, Mother Jones, October 27, 2011. If everyone’s income, rich and poor alike, had grown at the same rate since 1979, the average top 1 percent U.S. household would be making nearly $600,000 a year less and the average middle class household would be making $10,100 more.

Charles Blow, America’s Exploding Pipe Dream, New York Times, October 29, 2011. On the new Bertelsmann Foundation social justice ranking of the world’s developed nations, the United States ranks 27th out of 31. Only two of the other nations, Mexico and Chile, rank lower on the ranking’s income inequality metric.

Gar Alperovitz, How the 99 Percent Really Lost Out — in Far Greater Ways Than the Occupy Protesters Imagine, Truthout, October 29, 2011.

|

IN REVIEW

|

Why Economic Gaps Matter: A New Intro

Faiza Shaheen, Ten Reasons to Care About Economic Inequality. A New Economics Foundation briefing paper, London. October 2011.

Inequality knows no borders. Grand concentrations of private wealth, wherever they amass, always have the same impact. They squeeze out hope. They frustrate what our future could be.

That’s why this fine new pamphlet — from the British New Economics Foundation — makes such a useful global contribution.

Economist Faiza Shaheen has distilled decades of social science research on inequality into a breezy checklist that focuses primarily on the UK experience. But all advocates for greater economic justice will find this pamphlet valuable, no matter where they might live.

Each of the ten reasons for caring about inequality that this new briefing paper spotlights comes with a pithy, well-referenced discussion, a time-saving starting point for folks who’d like to dig deeper into each area.

Some of the ten reasons for caring about inequality presented here will likely already be familiar to Too Much readers. Others break some unfamiliar ground.

Author Shaheen, for instance, devotes one checklist reason to the spatial segregation that naturally evolves whenever income and wealth start concentrating. The more unequal a society becomes, the more rich and poor “live in different neighborhoods, go to different schools, shop in different places.”

This increasing separation generates a “social distance” that plays out in distrust within communities and an unwillingness to help others — or engage in civic affairs. Eventually, communities rupture. In the streets, people may even riot.

Shaheen and the New Economics Foundation will be releasing a series of additional new publications in the months ahead on various aspects of inequality. Those papers figure to have, based on this teaser, an eager global audience.

|

Too Much,is a weekly publication of the Institute for Policy Studies | 1112 16th Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, DC 20036 | (202) 234-9382 | Editor: Sam Pizzigati. | E-mail: editor@toomuchonline.org

|