Interview with Gaither Stewart

Conducted by Paul Carline.

GAITHER STEWART / Photo: A. Krynsky

Editor’s Note: With this interview we take pleasure in introducing our audience to the work of our European correspondent and senior editor Gaither Stewart as a novelist, and to Punto Press, a new publishing house affiliated with The Greanville Post. Its mission is to publish alternative voices not likely to be welcome at mainstream publishing houses, and to disseminate messages and ideas conducive to the deepening of authentic democracy and the dismantlement of the lies that support the current global status quo, which, as so many of our readers know, constitutes by now a gigantic edifice of hypocrisy and self-serving mythology. The Trojan Horse, the first volume in Stewart’s Europe Trilogy, is a very special—some might say unique—type of espionage thriller, a thriller with a serious message and a wealth of historical and political information. As Russian anthropologist Michael Korovkin has put it, the extraordinary value of this novel is not so much that it delves masterfully into thecomplexities of the human psyche, but that it focuses on a relatively little explored topic by the leading authors of our time, the uncomfortable issues of the terrorism hype permeating our consciousness and concomitant tension strategy.”

What is this “tension strategy”? Those familiar with Operation Gladio need no introduction to this rather disquieting and downright sinister topic (which is still very much alive). The Wiki, as usual, provides a terse but helpful summary:

The strategy of tension (Italian: strategia della tensione) is a theory that describes how to divide, manipulate, and control public opinion using fear, propaganda, disinformation, psychological warfare, agents provocateurs, and false flag terrorist actions.[1] The theory began with allegations that the United States government and the Greek military junta of 1967–1974 supported far-right terrorist groups in Italy and Turkey, where communism was growing in popularity, to spread panic among the population who would in turn demand stronger and more dictatorial governments. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategy_of_tension)

After 9/11 the strategy of tension received a huge injection of legitimation, thereby facilitating its spread and morphing, like a political cancer, into constant wars, destabilizations, and finally its crowning infamy, the rise of concepts like “homeland security” and the rapid erosion of Constitutional protections in the United States itself. Orwell himself could not have dreamed it up. If anything, due to the perfecting of modern propaganda tools, and the unquestioning of so much hypocrisy by the mainstream media (wanton accomplices in the crime), we live in a global society we could safely characterize as Orwellian alright, but on steroids. In this climate, which keeps worsening, we need more articulate voices to sound the alarm, and Gaither Stewart, via his Europe Trilogy, is one. In this interview, conducted by fellow editor Paul Carline, we get to know a bit more about Stewart, his background, and how he came to realize that an important part of his duty as a writer lay with focusing on the mechanisms by which the strategy of tension thrives in our midst.—P. Greanville

______________________________________________________________

The Trojan Spy

The Trojan Spy

Punto Press Publishing, 424 pp, 2012

Will be available for purchase in bookstores and online vendors by 20 April, 2012.

Address all inquiries or pre-publication sales to admin@puntopress.com

______________________________________________________________

Paul Carline: I’m curious about the man behind the stories – especially the three great stories which make up the “Europe Trilogy”. Great not just because they’re superbly accomplished as stories, with wonderfully interesting and engaging characters; but great – and also important – because they’re supremely relevant to the bizarre and dangerous world we’re living in. But to start on a lighter note: you have two most unusual first names: Gaither and Gwaltney, neither of which I’d ever come across before. What possessed your parents to give you such exotic names – and can you tell us where they come from?

G.S. My grandfather gave my father the names Gaither Gwaltney and he passed them on to me. Gaither normally only occurs as a family name in the US. I’ve never come across Gwaltney anywhere. In Italy, where I now live, Stewart is mostly used as a first name. The Italians had difficulty with Gaither and decided to turn it into Gaetano.

P.C. That’s fascinating. I love the resonance and the complementary oppositeness of those names – on the one hand Gaither the calm goatherder, alone on his peaceful mountainside, but having to cope with a bunch of sometimes ornery, individualistic goats (a bit like your characters), and on the other the fierce-eyed “battle hawk” or “wolf warrior of the plain” (two proposed meanings of the name, with a third possible connection with the famous knight of the Round Table, Sir Gawain). Do you feel the peculiar appropriateness of your names?

G.S. I’m not sure about appropriateness, but it’s a fact that when I was young I was ashamed of my names – precisely because they were so unusual. In later life I came to like them – for the very same reason.

P.C. But let’s go back to the beginning: where do you come from and what were your early influences?

G.S.I was born in Gastonia, North Carolina, but grew up in Asheville, which is where I really started out. Mine was a “working class” family, in old terminology I would say of the lower middle class, not poverty stricken, but not well off. My parents came from a semi-rural background; my favorite grandfather was a farmer and my father grew up in a family that produced everything it ate, except salt.

Knowing what is really important in your own childhood is no less elusive than establishing life’s turning points. But I can say with certainty that it is most significant that I come from a religious family. My parents too came from religious families, though their families were not as strict as my Southern Baptist parents became. How different things would have been for me if my mother had become a Methodist, as she nearly did—as she wrote in her memoirs, undertaken when she was ninety-three—because, as she said, of her fear of full immersion baptism. For a long time she believed being sprinkled would suffice for her spiritual needs. But in Mother’s words, the Lord helped her overcome her fears; she was baptised ‘properly’ and became a Baptist.

As time passed and I had contact with the Catholic Church in Germany and Italy, with Islam in Europe and the Near East, with Orthodoxy in East Europe and Jewish sects in New York, I concluded that it is best to stay as far as possible away from all organized religion. As a rule they cause chiefly suffering, war and pestilence.

That said, I consider myself a spiritual person, if that is the correct word. I often wonder if I am an unbeliever who wants to believe, or a believer who wants to disbelieve. In any case the concept of gods enters into my life. I use gods in the plural because I’m uncertain about monotheism, the cornerstone of our culture, for it seems the three monotheistic religions give mankind the most trouble. I was not at all put off by the polytheism of the ancient Mexicans I studied in Mexico; on the contrary, their images fascinated and comforted me. If life is an illusion, and maybe it is, then what are we to say about the gods of whom we are a part?

My battle between believing and disbelieving everything I ever believed I think created an atmosphere of unease in my life. I have always been unreposeful. The mother of an old friend in Frankfurt – when we were there together in the military – used to comment about the way I sit sideways at the table. She said I reminded her of her wayward husband, always on the point of jumping up and leaving. Yes, I am uneasy. Uneasy in life.

I still walk the cities we stay in, Amsterdam, Paris, Berlin, Buenos Aires, and peep into dark corners. Seldom do I pass by a passageway or a galleria without entering, looking for something, the something that can make a difference. My wife Milena says I am like a child, seeing mystery and magic everywhere. Though I deny it, it is probably somewhat true, for at my age I am still astonished. I don’t understand the world, but I still hope to.

I came to realize early that I didn’t want to exist only in relation to others. Being different became a goal for me, and also perhaps a mask, a costume. I have lost many things along the way but have also regained and reacquired others. Some people seem to be born rebels. I have always been a rebel who dreamed of being a revolutionary. I have come to detest and mistrust and resist authority and governments and directorates and control and command and leadership and hierarchy and their executives and bureaucrats and administrators and officials and clerks. For some reason I look down on the institutions of power and their executors and even hate myself for standing in one of their lines or for even being civil to them, so that I snow them with niceties just in oder to get away as soon as possible. I often think that Destiny could have dealt me other cards; I could have been born as Emiliano Zapata or Che Guevara and led the revolution in South America. In another time, in another link in the circle of life, maybe I will be Lenin. Borges believes we are everything and everybody in the circular life. Maybe this is childish nonsense – my immaturity again. Or perhaps I am expressing a repressed feeling common to everyone. I don’t know.

P.C. Did you read much as a child? What kind of stuff?

In my family environment, education was left up to the schools. So I did not learn to read at home and in fact learned to read fairly late, I think at around 8 years old. But then I gradually became a reader, enjoying adventure stories, like those by Jack London, and at some point I read about Mexico and the Mexican Revolution, Zapata and Pancho Villa, who for a time were my heroes. Later I dabbled in writing for my high school newspaper, with no great success – mainly because my chief interests then were girls and sports, especially American football which I loved. I got my first two years of college locally on athletics scholarships. But soon my chief objective was to get out of the South. Among my subsequent universities were Georgetown (Jesuits), UC at Berkeley (where I took Graduate Slavistics), and Munich University (where my course wasTurkologie).

P.C. When did you start to get serious about writing? Was that something ‘in your genes’ or in any way inspired by your home environment?

G.S. No ‘genetic predisposition’ that I’m aware of, although my father could tell a good tale. From early readings in adventure I leaped into rather esoteric fields which I could not really absorb. At the same time I came to like Scott Fitzgerald, then Hemingway (whom I can hardly read today), some of Thomas Wolfe (chiefly because he was from Asheville but also because he roamed over everything in life). I claim that Dostoevsky is my favorite writer, though I am uncertain about that. I loved Chekhov’s stories, and spent one cold winter in Germany reading Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina in Russian – which I considered quite an accomplishment.

P.C. I’m sure most would agree with that. What about your obvious love of languages? How did you acquire so many of them?

G.S. I started with Spanish while I was still living in America. I’m of a generation which was subject to compulsory national service. I was posted to Germany – this was, of course, during the ‘Cold War’ in Europe and America’s ‘hot’ wars elsewhere. I was in military intelligence. I spent a lot of my time studying languages – first Russian, then German. from the moment I arrived there, I felt I was finally ‘home’. Rather ironic, for most of my ancestors were in fact from Germany. But I meant both Germany and Europe. And in fact I have remained in Europe since. And I was determined to learn all the languages: I’d had Spanish in school in America, then Russian and German in the military, to which I added French at Berkeley, Italian in Italy, Dutch in Holland; I also studied intensively and quickly forgot Polish, Turkish, and Portuguese, so that today I try to retain the others while I’m presently studying Serbian.

I must say that I do not have a good ear for languages and learn visually and by long study. I once had a good memory so could memorize quickly but unfortunately forget just as quickly. I could always prepare for a final exam by practically memorizing the chief points of an entire course, repeat them on the exam, get a decent mark, and then promptly forget. Therefore I have truly forgotten more of my languages than I have retained. My speaking ability, let’s say, in Argentinian Spanish, is far ahead of my comprehension – my bad ear…

P.C. English has become the new lingua franca, the new Latin. There’s an obvious advantage to writing in English, but do you see any disadvantages? Is English in a sense the language of capitalism? Are you concerned about the not-so-subtle invasion of Western – especially American – mass culture through the dominance of English? Is there perhaps a special responsibility on English-speaking writers to point out the downsides of Anglo-American culture (perhaps that’s actually happening though the Internet)?

G.S. I think there is something in that. As a very broad generalisation, French and German are the languages of socialism – it was largely in Western Europe that the ideals of social democracy took root. I have found, in Italy for example, that some people are turned off by English. I tried writing in other languages – German and Italian – but it didn’t really work.

P.C. As an Englishman I’ve always found it interesting that while everyone has heard of the French and Russian, and perhaps even the Chinese, revolutions, very few know that the first popular modern revolution took place in England – also the home of that wonderful group of people called the “Levellers”. But with great stupidity and lack of foresight we allowed the monarchy to be restored – and we’re still saddled with it, and with the awful class system to which it gives a continued false legitimacy. Britain then emerged triumphant in the age of imperialism/colonialism and in the nineteenth century produced its ‘philosophical’ justifications – in social and economic Malthusianism and Darwinism, among others – for what then evolved into “winner take all” capitalism. Socialism had a brief flowering after WWII before ‘old money‘, the City and class reasserted themselves aggressively with Thatcherism. But Britain also produced the likes of Dickens and Orwell, outspoken critics of the system.

So out of choice as well as ‘destiny’ (military service) you came to Europe – first of all Germany. You said you finally felt “at home” there. Can you say why? What was it about Europe that felt so ‘right’ to you?

G.S. Yes, Germany was my first country, chiefly during the Cold War. But I loved all of Europe; Italy and France especially fascinated me. But already then East Europe interested me, especially Russia. I thought constantly about Russia and how to get there even in that Cold War atmosphere. That desire got me into hot water more than once in later years.

I became interested in the idea of a united Europe quite early – so you can imagine my disappointment when it turned out to be not a union of people but of one of banks, finance, and capitalism. I had become quite Eurocentric and began thinking of escaping from that – one of the reasons my Italian wife, Milena (a second marriage), and I moved to Mexico in the 1990s with the idea of abandoning my beloved Europe and staying there as “emigrants” – this emigrant thing again! But also I was writing a novel, half of which is set in Mexico. After 18 months, Mexico had not worked out; we had chosen the wrong place to live. So we moved to New York, where we had a very small apartment on Central Park! I went with the idea of rediscovering America but ended up in a Russian-Italian environment and hardly got to know any Americans. There I finished the Mexican-Italian novel, Walks of Dreams, still unpublished, and wrote a dozen or so short stories about Mexico, most of which were published in my short story collections and/or in online literary publications. Milena began missing Italy; I missed Europe. And we returned “home”.

P.C. Your interest in socialist/Marxist theory and practice … where does this come from, and when did it become really important to you? Was there a conscious sense of going against your American roots?

G.S. After my interest in the Mexican Revolution I became interested in the Russian Revolution, and from there straight into Marxism/Leninism. That developed more finely in Europe. I have done wide readings and study in the field

And most definitely in this time I was conscious of the anti-Americanism in the world, in me. Much of this is because of the wars; I am very anti-war in any form. Not to be confused with the idea of violence, about which I have rather confused ideas. I don’t believe the capitalist system will ever back down to non-violence, though I fear where violence can lead.

Moreover, I do not like the insipid so-called American way of life. I detest backyard barbecues, fast foods and little green, yellow, red and blue flags waving over mile after of mile of gas stations, used car lots and fast food stops, pledges of allegiance and all that crap.

P.C. Even ‘socialism’ is a ‘dirty word’ in America – never mind ‘Communism’. The propaganda message that ‘capitalism’ won – that the socialist experiment failed – is still very strong. The ‘Old Left’ seems increasingly irrelevant; they even reject the fact of state-sponsored terrorism, which is a major theme in your trilogy. At the same time it is abundantly clear to many that predatory global capitalism has failed as an ideology – but it is still able to cling to power because it controls the levers, despite being terminally rotten at the core. Do you see any green shoots of a new form of socialism which can overcome the stain of the Stalinist, Maoist and other failed forms of socialism – which for many Europeans are very recent still? Is it possible to reconcile individualism and socialism – perhaps in a purer version of the French revolutionary ideal of liberté, égalité, fraternité, which is still waiting to be realised?

G.S. The social/welfare state arrived in Europe after 100 years of labour struggles. Over the past decade especially, we have seen the new Europe (the expanding EU) encroaching on this legacy. It’s indicative that the first ‘reforms’ implemented as a response to the current debt crisis hit the ‘soft target’ of welfare provisions i.e. the poor are always held to blame (while the rich get ‘bailed out’ and still get their bonuses).

In the US, the word ‘socialism’ is in cautious use again. There are ‘socialist’ candidates in some states – but I’m not sure what the label really means.

P.C. When did you first begin to realize what was happening with (Anglo)-American imperialism? Did you study the origins of WWI and WWII, for example – not the ‘official’ story, of course?

G.S. Oh, yes, I think I became aware of this early. Especially in Italy and France, but I remember too the Rote Armee Fraktion in Germany in that respect, I mean Vietnam affected all our lives and still does today. America has still to admit that the Vietnamese beat the shit out of them.

Yes, I have read widely, and studied the origins of both world wars. The awareness that false flag operations were employed then and have been used forever is a lesson for everyone. A hard lesson for Americans and Europeans, too.

P.C. What about spies and spying? Does your writing on this come from direct personal experience? Where does the character of Nikitin come from? When did the idea for a spy story emerge – did it just crawl out of the Berlin ‘woodwork’?

G.S. In Rome I got to know a real spy in the US Embassy. He was rather absurd but entertaining, not especially literate but no mercenary soldier as are many today. His easy-going character you find in my character Robert, Nikitin’s first contact in Munich. I really don’t remember what sparked the idea of Nikitin, but at a certain moment I began imagining such a person – and he is completely imaginary. I saw him immediately as a man first of all uprooted, but without firm allegiances, a freewheeler, who nonetheless was concerned about the question of loyalty – even though he was uncertain as to loyalty to what. In the end he is not even loyal to Masha, though he loves her.

Yes, again, the idea of a long spy story emerged from the stories in Once In Berlin. However I knew immediately that my heroic spy – Nikitin- was a sensitive, thinking man and that his real story would be introspective. He was homeless, truly a heimatloser Auslaender, as was Karl Heinz and subsequently Cliff and finally Elmer. They all, I see now, I believe: they all reflect my own rootless character, deraciné, with little sense of belonging. And therefore my concern with questions of uprootedness vs fixedness. That people who stay in one place are flat characters, as E.M. Forster writes in his Aspects of the Novel. While the uprooted become rounded characters, but infected with big doses of nostalgia, unbelonging, unknowing, and full of bewilderment at the miracle of life.

P.C. Your love of and feel for place … what fostered that? Europe as a fascinating patchwork in contrast, for example, to the uniformity of large parts of America? Do you, like Cliff, immediately ‘go walkabout’ in any new city you visit? It feels as if you have definitely been to every place that features in your stories. I’m guessing you like maps ….

G.S. Most definitely. As I mentioned earlier I am an urban walker. A hiker; once in the mountains too but now chiefly in cities. Everyplace I have gone in my life, my first act is to walk it. I love to walk big cities. Methodically. Using maps to do it. Rome, Paris, Munich, New York, Buenos Aires. I once walked the length of Broadway from the Battery to the top of Manhattan. I walked most of its crosstown streets from the Hudson to the East River. I have walked every arrondissement of Paris, every barrio of north Buenos Aires. Each systematically, with a plan.

P.C. Re the Trilogy: was it always your plan – or did the idea come first simply to write a sequel to The Trojan Spy? In the development of the plot through the three books we come more and more into the present political reality (even the future!). Was there a growing sense – when? – that there was an urgent need to inform and warn a wider public about what’s really happening … and that you could do this better through a novel than by writing ‘political’ articles?

G.S. No, I did not plan a trilogy any more than I plan a novel as such. The characters grew, the plot broadened, one thing led to another, and voilà, I was into Lily Pad Roll: the idea and the title came to me suddenly, all in one day, shortly after the Trojan Spy ended. From that it was a short step to the exile of Elmer, who in his uprootedness is emblematic of most of my characters.

I suppose I have wanted to inform – to that extent my writing could be labelled ‘didactic’. But that is not really my intention, even if such things need to be said. All in all, I hope any kind of illumination emanating from here comes from the development of the characters themselves; that is, that (their) internal, interior, loneliness, seeking, unknowing, deracination illuminate the external, the exterior of the bewildering, false, misleading, mendacious events of our times.

P.C. You mentioned earlier your fascination with Russia. What do you think is happening in Russia? Can it be a bulwark against American expansionism/imperialism? Has it lost the plot and become a mafia state – or can it rediscover its soul?

G.S. Most certainly I count on Russia. As you see in Lily Pad Roll. Of course my hope placed in Russia expresses also my damned Eurocentrism and ignores Asia, the future of which I can’t grasp. But America’s fear of Russia and the Russian idea of Socialism, in fact of any messianism that does not come out of ignorant America, underlines Russia’s important role as a brake on American greed. I still find it curious that Russia has seldom had troops stationed abroad – here I’m not counting its occupation of the Baltic States or the post WWII events in Eastern Europe. But Russia today? It has no troops abroad. The US? Troops in 147 countries.

P.C. Your deep interest in, even fascination with human psychology …. when did that start? Likewise your obvious need to create believable characters (rather than stock stereotypes – the rogue CIA officer/politician etc.) and to explore their motivations and reveal their human soul-searching – even with your ‘nasty’ Raymond character (in Lily Pad Roll)! Also your interest in the possibility of change and ‘redemption’ in a human being (Cliff, Nicola, Masha and others).

G.S. The idea that the human being can change remains fixed in my own psychological makeup. Many of my characters seek redemption though seldom do I explain clearly the reasons for their search. Perhaps simply because they are human beings. I suppose Dostoevsky stimulated my literary interest in the topos. I’m really less a storyteller than a seeker of understanding of what our lives are all about. This must reach back to my childhood, the Church I came to despise, the hypocrisy within it and in many of its people.

My parents, whose religion I rejected, however bestowed on their three sons much love. And if my mother at 100 years of age still prayed for my soul and my personal redemption, she accepted my unbelieving; she accepted me. Since it all seems to be about love, that is not a bad foundation.

P.C. Gaither Stewart … thank you so much for this interview. May I wish your trilogy the success – and the psychological and hopefully also political effect – it deserves.

__________________________________________________

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWER (in his own words)

Paul Carline, vintage 1944. English, but have hopefully by now acquired honorary Scottish citizenship, having spent more than half my life there. Currently resident in southern Scotland. Writer, translator, musician; passionate about truth and justice – which involves making the effort to identify truth and separate it from half-truth, fiction and outright lies. Given that most common understandings about the nature of reality, history, politics, society, economics etc. are false and serve mainly vested interests, the task of exposing the lies and abuses of power is more than a full-time job. Fortunately, there are many who feel called to the same mission.

Gaither Stewart’s The Trojan Spy, second edition, is scheduled to appear this Spring.

BEGIN HERE

_______________________________________________________________________________

¶

ADVERT PRO NOBIS

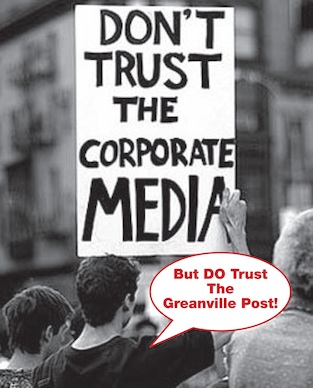

IF YOU CAN’T SEND A DONATION, NO MATTER HOW SMALL, AND YOU THINK THIS PUBLICATION IS WORTH SUPPORTING, AT LEAST HELP THE GREANVILLE POST EXPAND ITS INFLUENCE BY MENTIONING IT TO YOUR FRIENDS VIA TWEET OR OTHER SOCIAL NETWORKS! We are in a battle of communications with entrenched enemies that won’t stop until this world is destroyed and our remaining democratic rights stamped out. Only mass education and mobilization can stop this process.

It’s really up to you. Do your part while you can. •••

Donating? Use PayPal via the button below.

THANK YOU.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

One Response to Interview with Gaither Stewart