Colorado, in June

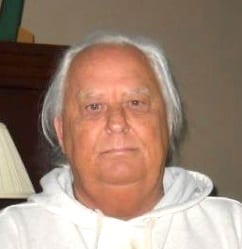

Mike Ingles

I was twenty-three, Danny was twenty-four. It was just a June from the ‘Summer of Love’ and just a June until ‘Woodstock’. It was 1968.

It was a Monday in June, we left Ohio for California in a 1962 Impala. States went flying by, we counted how many empty beer cans it would take to cross each state, we would throw the empties into the backseat, and when we crossed a state line we would stop and count them. Ohio was the fewest, only twelve. Colorado was the most, thirty-six, because we had to stop often just to take in all the beauty. The envious green mountains collided with red hues of glaciated canyons, were countered by blue and white waterfalls here and there. Danny said he wouldn’t live in Colorado, it is too special. He often said, Colorado is a place no one should be allowed to live; there should be a law – you can only enter Colorado on a three-day pass.

Danny had a gregarious personality, he smiled and talked fast because he was so excited, his presence was as big as Colorado. We left Ohio on a Monday, he just received his MA in Journalism, and I had dropped out, giving up on three and a half years of college. I had learned all I wanted from the university, not all I could have learned, but enough. I had written a play. “Cornbread and Pumpkin Pie”. We were going to be rich and famous. I would write, Danny would handle the production and script. We stopped in Vegas, we dressed up in the only suits we owned, and we drank martinis and pinched every cocktail waitress we could lay our hands on. They didn’t mind. They knew we were from Ohio and would leave a nice tip. It was the first time I had seen a woman in black hose and white lace. To this day I remember her. It was a wet dream, until I was thirty or so, now it’s just a peaceful remembrance, it’s a fantasy I cherish, I keep it tucked away, and it is pristine, like Colorado.

It took us a week to land in Hollywood. All glitter and grease. The hippies strode up and down Vine Street. Colorful vagabonds by day, but at night they hid in doorways and whispered, we could see the glow of their cigarettes reflecting the dark. They were honest and happy, until the night and then they became harsh and talked of hate and ideological change. They listened to Dylan, they thought he was a kind of God. They envisioned a world free of war, pain and suffering. They were naïve, they did not understand the human condition, and we were naïve, Danny and I. We moved into a one bedroom flat, on Locum Street. Seventy bucks a month, no hot water. I bought a used Underwood typewriter and started the revisions. We called every agent, every producer and every studio in Southern California. I took a job as a short order cook. Danny tutored Southern Cal undergrads. We dated two girls from Iowa; they were going to be stars. The ‘pill’ had just been introduced, so we made love almost every night. Sheila was my girl’s name. I have forgotten the name of Danny’s girl. I bought Sheila black hose and a white lace garter belt at some sex store on Vine Street, but she wouldn’t wear them. She was a very liberated lady, she asked me to wear them. They were too small. It was on a Monday in September, I had a response from a small studio in Palo Alto, they did not like the play, but would I be interested in writing commercials for television? One hundred and fifty bucks a week! Sheila had given up; she was going home to Iowa, black panty hose and all. She was heavy into acid and she was scared. So was I, so was Danny.

Months went by. Danny started working as a chauffeur for a limousine company. I wrote jingles. Want to hear a famous one?

If you want fun with all your shoes, Get Keds, Kids, Keds.

It took three of us almost four months to come up with that little ditty. I got a fifty-buck bonus for that one. I was rolling in dough and writing at night. Danny drove famous people at night and did lesser drugs during the day. He worked diligently for a cause. Any cause. He spoke endlessly of civil rights and voter registration. In the fall he worked on the campaign for Robert Kennedy. I wrote TV commercials and in my spare time I wrote terrible poetry, trying to emulate Jackson Pollock. Danny drove Sean Connery to the Oscars; he waited for the great man in the parking lot and got high. Sean did not win. On the way home Danny ran a red light and hit a cab. Everyone was all right, no one was injured. But Sean had to make a big shit and called Danny a ‘hopeless idiot!’ Danny refused to allow the ruling class to belittle him; he punched Sean in the belly. 007 doubled up in a tight ball, lying on the concrete. Danny’s career in California was through. Within a month he went back home to Ohio and got a job with the Columbus Dispatch. He has two children and four grandchildren now. They don’t know about our California odyssey. I wrote a book and then another and then another. I think it’s eight now. My books are not released in hardback; I am a paperback writer. In 1986 they made a movie out of one, I no longer own the rights, so I am unable to give you the title. They wouldn’t let me do the screenplay. I had no experience. The critics dumped it, rightfully. Danny has won several prizes for his newspaper writing. He has had his own column since 1981. They want to make a movie about my latest novel. I have agreed, but only if I do the screenplay. They said they would get back to me. You may never see the film; I won’t let them make it unless I do the work, or I get a lot of money. It’s a story about a cross-country trip; it’s a coming of age story. I called Danny, I asked him, if I flew out to Ohio would he consider driving to California with me? I would buy a 1962 Impala and buy the first case of beer. We could just drive along in a time zone called 1968, in some kind of 60’s time warp, we had plenty of time to watch the miles go by. He said he didn’t think he could make it past Colorado. I said it’s a nice place to stop. “Yeah,” he said, “It would be a great place to stop.” I had a friend of mine back home in Columbus; I called him and asked if he would find a restored 1962 Impala. The best he could do was a 1963. They are practically the same, or at least they seem so.

It was a Monday, the summer equinox, the longest day of the year. I packed light, so did Danny. But we had a lot of medicines to carry and that damned oxygen tank. We placed it in the back seat, he didn’t need it all the time, just when he lungs started burning he said. Danny had asked his doctor about the trip and the Doc advised against it. Danny’s wife of twenty-nine years said to hell with doctors, the fresh air will do you good. Her name is Dee, I think I am in love with her. She is the most compassionate and loving person I have ever known. Before we pulled out of her driveway, she kissed him through the rolled down window. It was a long kiss. She touched his head and ran her fingers through what was left of his hair. They whispered something to each other. It would be their last kiss and they knew it. I popped the first can, but Danny did not feel like a beer. He had lost over sixty pounds. He was the same person inside, but outside the years and the cancer had taken their toll. I made him promise me he would at least drink a beer at every state line. We hit Indiana and he sipped a Miller Light until it was warm. He fell asleep. I stopped at a roadside rest and went into the restroom and wondered about this crazy excursion, I wondered if I shouldn’t just turn around and go back. Take him back to the people who loved him and could care for him. To be honest, when I called and asked him to go on the trip I never figured he would go. Danny always surprised me. I sat on a toilet and cried.

We passed the Illinois line. I shouldn’t have been driving. I brought along some CD’s of The Stones, The Rascals and of course Dylan. Danny would sleep most of the time, but when he was awake we would reminisce. When we got to the Missouri line, I suggested we take a detour north to Iowa and try to find those farm girls, but Danny said no. He was with the only woman he had ever really wanted. I asked, just out of curiosity, what was the Iowa girl’s name? Denise, he whispered, we called her Denny, remember? Ah, that’s right I remember. Just outside Missouri we stopped at a Holiday Inn. He didn’t feel like eating out, so I ordered room service. He waved his fork across the plate a few times, but he ate almost nothing. The thing was, he never smoked. Me on the other hand, I smoked all the time, I still do, and I can’t write a sentence without one burning in the ashtray. In the morning he was not doing well. Sometime during the night he had attached the oxygen tank. I was up at seven, but I wouldn’t wake him; it would have been cruel. At about 11:00 am I heard a faint gurgle and his eyes opened. I held his hand and his eyes swore into mine. “Let’s go to Colorado,” he said in a culminating garble. “All those mountains, all those mountains.” He tried to say something else but I couldn’t understand him. There was this great sigh and his chest inflated air, I didn’t hear him exhale, and then he was gone. I had promised Dee, if anything were to happen along the way I would call her. That would have been the right thing to do, I guess. Call Dee and then the authorities. I sat for awhile thinking out loud. If I tried to take him to Colorado I would probably be breaking some law. It wouldn’t be fair to Dee to take a dead man five hundred miles. But the bottom line was, I wanted to see Colorado again, I wanted to see it with my friend. We left just after twelve. I stopped and got a case of Coors. We drove through Kansas with the CD player set at full blast. ‘Get Off Of My Cloud,’ ‘A Girl Like You,’ ‘Like a Rolling Stone.’ Danny reminded me of our little flat on Locum Street, “Nothing but cold-ass water.” He laughed insistently. We talked about the hippies and how I thought he might be one. I told him about buying the black stockings and white garter belt. I was so ashamed buying them at that pervert store on Vine Street. He said Dee had an outfit like that, but he only got to see it about twice a year. He was drinking way too much. I told him to slow down or we would run out of beer way before Colorado. He said to hell with it, stop and buy some more. We stopped somewhere in Kansas, I bought another case of Coors. ‘Grooven,’ Lady, Lay, Lay,’ ‘I Can’t Get No Satisfaction,’ I counted the empties, twenty-four for Kansas, they lay all over the back seat.

Colorado! I got off the interstate and took back roads. We talked about the great Sean Connery. Danny said he would do it all over again, I believed him. We talked about sweating in a tiny apartment with no air conditioning. I wanted this ride to last; I had waited an eternity for it. We got to the canyons, it was nearly dawn, and the canyons were blue and orange. Danny read the map, and then suddenly he became very still. We had driven all day and all night. The Sun was breaking a new day just over the green mountains. I helped him from the car. We sat alone by some unknown highway, our backs against a stone from a million years ago. I drank a beer and put my arms around him. He was cold. I could hear the music playing in the car “It’s a Beautiful Morning.’ I sang along- “I think I’ll go outside for a while, and just smile, for awhile.”

© 2003 Mike Ingles

Mike Ingles is a freelance writer living in Ohio. He has a degree in American Literature from Franklin University, Columbus, Ohio.

duckrun2@aol.com