BY STEPHEN GOWANS, What’s Left

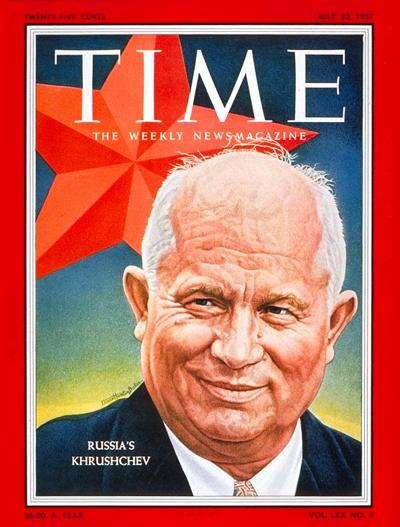

Khrushchev’s revisionism refers to claims by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev that:

Khrushchev’s revisionism refers to claims by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev that:

• Socialism can be brought about by peaceful, constitutional means within capitalist democracies.

• Socialist and capitalist countries can coexist peacefully.

Was he right? Did he really believe these claims?

Socialism, if it is understood as a publicly owned, planned economy, has yet to be brought about through peaceful, constitutional means within capitalist democracies, or elsewhere, and it is difficult to imagine conditions under which it ever could be. In order for socialism to be achieved at the ballot box, the wealthy and powerful who dominate the state, including its police, security, and military apparatus, would have to stand idly by as their private productive property—the basis of their wealth and privileges—was denied them and brought under public control. This is unrealistic. We cannot imagine slave owners peacefully standing by, as their slaves set themselves free, nor feudal lords peacefully accepting their serfs’ expropriation of their estates. Unless we believe that capital-owners are somehow unique, we should not imagine that they would be any less likely than other ruling classes to use the repressive apparatus of the state to preserve their privileges and beat back challenges from a subordinate class that seeks to abolish private productive property.

Did Khrushchev really believe what he was saying? Perhaps. But his arguments may have had less to do with what is true, and more to do with what suited the interests of the Soviet Union at the time (and some might also say what Soviet leaders believed was best for advancing the interests of the international working class given the formidable obstacles in its path.)

The USSR desperately needed space to develop its economy, free from the continual threat of military aggression from the United States and its NATO allies. For his part, Stalin had dissuaded communists in France and Italy from making insurrectionary bids for power at the end of WWII, when communism’s reputation was strong and war-torn Europe leaned toward socialism. He also refused aid to the Greek communists in their guerrilla struggle against British occupation. These efforts to put the brakes on communist advance in the West were taken in order to maintain friendly relations with the USSR’s wartime allies and also because Soviet-supported revolutions in France and Italy would likely have been crushed by the Americans and British, who would have then turned their guns on the Soviet Union. Stalin’s understanding was that a quid-pro-quo had been worked out with his wartime allies. He would not interfere in Western Europe and in return, they would allow him to establish friendly “buffer” states in Eastern Europe as a safeguard against another invasion of the USSR from the west. Likewise, Stalin exercised extreme caution in helping Kim Il Sung in the Korean civil war for fear of being drawn into war with the United States. The Soviet Union could ill-afford a war with the Americans, and Stalin therefore refused to support revolutionary movements in his allies’ sphere of influence and acted with caution in supporting revolutionary movements elsewhere. There is a considerable continuity in Stalin’s efforts to keep the hostility of capitalist powers at bay, and Khrushchev’s call for peaceful coexistence.

Since it was Khrushchev who proposed peaceful co-existence, he had to offer an incentive to interest the Americans. The incentive was the idea of a peaceful transition to socialism—in effect, a promise that communist parties in advanced industrialized countries would work within the rules of capitalist democracies, and renounce violent, extra-constitutional bids for power. To put it another way, they would surrender any possibility of being a threat. This was very much like the bargain Stalin tried to strike with his wartime allies. Refrain from interfering in my sphere and I will refrain from interfering in yours.

While it irked some communists in the West, peaceful transition was a concession of little significance. Most communist parties, most of all those in North America, Western Europe and Japan, were not in a position to make violent, extra-constitutional bids for power. Therefore, if the Americans took the bait, Khrushchev would get space to continue to build socialism for the small price of giving up revolution in the advanced countries, which was not on the radar anyway.

Was this a betrayal of the working class outside the Soviet sphere? It depends on what you think the chances of revolution were in the advanced, industrialized countries. After the failure of a revolution to come off in Germany following the Bolsheviks’ seizure of power in Russia—a revolution Lenin and his followers had fervently hoped for and expected, even depended on—the Soviets were never again sanguine about the prospects of the working class in the West overthrowing its capitalist masters. Therefore, beginning with Stalin, the Soviet Union redefined the idea of internationalism to recognize this depressing reality. Moscow would refrain from vigorously supporting working class struggles in the West, first because the pay-off was likely to be slim to non-existent, and second because the costs were too high, namely the risk that Germany, Britain and France, and later the United States, would retaliate and threaten the USSR’s very existence.

Instead, the Soviets turned their gaze to seemingly more promising and safer horizons, one on their periphery and the other in the national liberation movements. They would expand socialism gradually, by drawing more and more of these countries and movements into their orbit. Meanwhile, the appeal of socialism in the industrialized countries would be heightened by creating within the Soviet Union a living, breathing, example of socialism. If the Soviet Union could overtake the United States economically, and produce a society of plenty with a growing array of publicly provided goods and services delivered according to need, workers in the West might be galvanized to overthrow the capitalist class, which stood in the way of their achieving the same. However, the only way that this could be brought about would be to set the US-USSR relationship on a footing of peaceful co-existence and economic, rather than military, competition, allowing Moscow to divert capital and manpower from the military to the civilian economy so that it could advance toward a society of plenty.

Khrushchev’s revisionism, then, can be seen as a clever detour around hazards that blocked the Soviet Union’s path toward building a stronger socialism, and eventually, socialism on a global scale. Clever as it was, it had a fatal flaw: it was too successful. Peaceful co-existence and detente gave the Soviets space to do two things:

• Beat the United States into space.

• Produce economic growth so rapid that the United States believed it would be overtaken economically.

Alarmed, the Americans resolved to deny the Soviet Union the space it needed to continue along this path. Eventually, Washington used an arms race to severely retard growth in the Soviet economy, and force the USSR into submission.

To sum up: There is no substance to the idea that capitalism can be abolished within capitalist institutions while capitalists stand by idly and allow their property to be expropriated. Nor is it reasonable to suppose that capitalist powers are prepared to co-exist peacefully with socialist ones on a permanent basis. They may do so for a time, if the costs of war are too high, but they will be forever driven to capture the economic space socialist countries deny them. All the same, Khrushchev’s peaceful co-existence proposal was less a statement of fact and more a proposal for a modus vivendi—you let us be, and we will let you be. The merits of the proposal can be evaluated on the grounds of whether it achieved what it was supposed to achieve. It did, for a time, reduce tensions between the two powers, but failed inasmuch as the United States eventually abandoned detente. Still, we need to ask whether the alternative—allowing tensions to escalate and trying to foment revolutions in the West—would have worked out better. This seems unlikely. While the Soviet military was formidable, the economy of the USSR was still smaller than that of the United States and was therefore incapable of supporting Soviet participation in the Cold War indefinitely. Eventually the Cold War took a heavy toll on the Soviet economy. Moreover, workers in the West showed no strong inclination to overthrow their capitalist masters.

We should be clear, too, that Khrushchev represented no discontinuity with Stalin. Stalin too was interested in a live-and-let-live foreign policy if it contained tensions and allowed the USSR breathing room to grow stronger. There were, then, good reasons why the Soviet Union should have worked for detente, and Moscow’s demanding that communist parties in advanced industrialized countries adopt a non-revolutionary politics for non-revolutionary times was hardly a high price to pay.

A final point. The problem with the idea of “non-revolutionary politics for non-revolutionary times” is that revolutionary times can creep up unannounced, creating missed opportunities for parties that are contingently practicing non-revolutionary politics, or have institutionalized them. The trick, obviously, is to avoid either of the following errors:

• Practicing non-revolutionary politics in revolutionary times.

• Practicing revolutionary politics in non-revolutionary times.

Of the two, the first, of course, is the gravest error. It could be said that Khrushchev’s revisionism guaranteed that if any error were to be made, it would be this one.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Srephen Gowans is a Canadian activist and political analyst. He is the founding editor of What’s Left.