By Rodolfo F. Acuña

“The consciousness of a worker is not a curve that rises and falls with wages and prices; it is the accumulation of a lifetime of experience and socialization, inherited traditions, struggles successful and defeated . . . It is this weighty baggage that goes into the making of a worker’s consciousness and provides the basis for his behavior when conditions ripen . . . and the moment comes.”– E. P. Thompson

In talking about the working class as of late I feel like Solomon “Sol” Roth in the futuristic movie, Soylent Green (1973): “There was a world, once, you punk.” Det. Thorn: “Yes, so you keep telling me.” Sol: “I was there. I can prove it.” Det. Thorn: “I know, I know. When you were young, people were better.” Sol: “Aw, nuts. People were always rotten. But the world ‘was’ beautiful.”

History is about feelings, and in order to understand it, you have to understand people. British historian E.P. Thompson had a love affair with the working class (not classes); he believed it was the motivating force behind most economic and social progress. Thompson could have easily been Sol except for the fact that his love affair was with the English working class.

In my case, I try not to romanticize the working class; at the same time, I consider many workers my teachers. I was very fortunate in the 1980s to have been part of the Keep GM Van Nuys Open campaign.

I will never forget an auto worker who told me that the thing that he would miss most if the plant shutdown was the feeling that he got after his shift was done and thousands of workers would pour into the parking lot. He felt overwhelmed, he was powerful, and he had a union.

Few areas of labor reflect more racism, ignorance and misunderstanding than the treatment accorded migrant workers.

During the GM struggle, I attended many meetings where I mostly listened. At one meeting at the International Association of Machinists Union Hall in Burbank, I sat next to my friend, Eloy Salazar, who was a member of the Machinists. He was proud of his hall and how Mexican Americans had played a leading role in the union. After the meeting he asked me, “Rudy, you got a minute?

I want to show you something.”

We went out into the lot where his new car was parked. It was a Cadillac, which he pointed out was an American made car, white with white leather seats. It kind of took me aback because in my world of so-called “cultural” workers there would have been instant criticism such “bourgie”. I reflected how Eloy who had worked hard as a machinist was proud of the product of his labor, and how in contrast I was apologetic for my Ray-Ban sunglasses. My world was one of theory; Eloy’s was one of the praxis.

My research put me into contact with labor leaders. Exploring the Great San Joaquin Valley Cotton Strike of 1933, the name that kept popping up was that of Pat Chambers, the lead organizer for the strike. Pat had done oral interviews for the Bancroft Library, but if he was alive I wanted to see him. It was forty years after the fact so I sent out numerous emails.

One day he showed up at the Cal State Northridge campus and asked for me. When I heard he was there I was excited. Pat was a short man, 5” 6”, rotund and balding. He apologized for taking so long but he had to check me out, and it was important to him that I was an activist. In the next several years he would just show up, and was clearly emotional to see so many Chicanas/os in college.

[pullquote]“Caroline Decker, who had dropped out of school to help organize oppressed workers, was a communist because she was anti-fascist, and the Party was the only organization doing something about it, according to her. Years later when interviewing strikers, they would ask about Caroline Decker.”[/pullquote]Chambers was a pseudonym; he was a communist who at the time were hounded. Pat did not like the party leadership, saying that they caused too many problems and cost resources to hide them. It was clear that he was not an ideologue; he got into the party because he admired the Wobblies.

The strike involved 18,000 cotton pickers and their families; 80 percent were Mexicans. It was a violent strike that saw three Mexican workers assassinated on picket lines at Pixley and Arvin. He described the Mexican women as the warriors who picketed and kept worker camps such as the one at Corcoran operating. The growers in collusion with the American Farm Bureau and the Chamber of Commerce kept the sheriffs and the elected officials pro-grower. To break the strike county and state officials denied workers relief and pressured the women to go back to work. Growers purposely starved at least nine infants to death.

There were few organizers other than Chambers and 4’ 8” Caroline Decker who was in her late teens or early 20s. Caroline was from a middle-class Jewish family; she dropped out of school to help organize oppressed workers. She was a communist because she was anti-fascist, and the Party was the only organization doing something about it, according to her. Years later when interviewing strikers, they would ask about Caroline Decker.

The strike drew celebrities such as Ella Winters and Langston Hughes. John Steinbeck interviewed Chambers and others about the bitter Taugus Ranch and the Cotton strike. Steinbeck modeled the protagonist after Pat.

Yet although the overwhelming majority of the strikers were Mexican and a minority black, Steinbeck decided much as in The Grapes of Wrath to whiten the characters and make them White Oklahomans because he did not believe that his readers would be sympathetic to Mexicans or blacks.

In 1934-5, the growers and their minions finally broke the union. Chambers and Decker among others were charged and tried for Criminal Syndicalism: “Any doctrine or precept advocating, teaching, or aiding and abetting the commission of crime, sabotage or unlawful acts of force and violence or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing a change in industrial ownership or control, or effecting any political change.”

Chambers and Decker along with other union organizers were convicted. Chambers spent two years in San Quentin, and Decker two at Tehachapi Women’s Prison before the convictions were reversed on appeal.

After this point Chambers dropped out of the Party and he went to work as a laborer. His last years were in the Local 51, San Pedro, California, of the International Pile Drivers Union.

Pat thought he had been forgotten. He was excited about the gains made by the farmworkers under César Chávez. In summer 1971, as Marc Grossman, a Chávez aide, tells it, Chambers went to the UFW’s headquarters just outside Delano. Chávez’s secretary informed Chávez that “an old guy” was in the lobby, asking to speak to someone about times past, Chávez answered, “I’m busy, have him talk to one of the organizers.“

About three hours later the secretary said the old man hadn’t left. “What’s his name?” Chávez asked. “Pat Chambers.” Chávez’s face lit up. Chambers, Chavez, and the UFW driver spent the rest of the afternoon driving around Delano.

Chambers had avoided visiting Delano during the five-year grape strike out of fear Chávez would be redbaited because of CAWIU’s Communist ties.

The Moment had arrived for workers in the 1930s. This was especially true of Mexican women who produced outstanding leaders such as Emma Tenayuca who I met at an activist reunion in San Antonio in 1989. At the age of 16, she began organizing workers. Emma was the lead organizer in the San Antonio Pecan Shellers’ Strike. Jailed and hounded, “when conditions ripen . . . and the moment” came she rose to the occasion, and we learned from her “struggles successful and defeated . . .” form our consciousness.

_______________________________

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

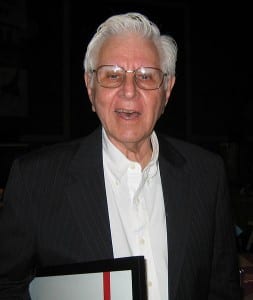

Rodolfo Francisco Acuña, Ph.D., (born May 18, 1932) is an historian, professor emeritus, and one of various scholars of Chicano studies, which he teaches at California State University, Northridge. He is the author of Occupied America: A History of Chicanos, which approaches the history of the Southwestern United States that includesMexican Americans. It has been reprinted five times since its 1972 debut. The sixth edition was published Dec. 1, 2006.[1] He has also written for the Los Angeles Times, The Los Angeles Herald-Express, La Opinión, and numerous other newspapers. His work emphasizes the struggle of the Mexican American people. Acuña is also an activist and he has supported the numerous causes of the Chicano Movement.

Rodolfo Francisco Acuña, Ph.D., (born May 18, 1932) is an historian, professor emeritus, and one of various scholars of Chicano studies, which he teaches at California State University, Northridge. He is the author of Occupied America: A History of Chicanos, which approaches the history of the Southwestern United States that includesMexican Americans. It has been reprinted five times since its 1972 debut. The sixth edition was published Dec. 1, 2006.[1] He has also written for the Los Angeles Times, The Los Angeles Herald-Express, La Opinión, and numerous other newspapers. His work emphasizes the struggle of the Mexican American people. Acuña is also an activist and he has supported the numerous causes of the Chicano Movement.

His mother Alicia Elías was from Sonora, and his father from Cocula, Jalisco. His academic counselor advised Acuña to teach “Spanish” or “Physical Education” because “Mexicans don’t have a history”. This infuriated him, an outrage that led him to pursue a doctorate in history. His specialty was northern Mexico and the Mexican origin of people in the United States. His study led to his participation in the movement to begin Chicano studies, giving a voice to Mexican Americans in education and history. Through research and action he evolved into a Mexican American historian.

Illustrations:

Google images are becoming like an archive of links to digital photos

The following are selected links:

http://www.farmworkers.org/strugcal.html

http://www.ourhistoryasnews.org/lc-1933-cotton-strike

http://as.sjsu.edu/steinbeck/teaching_steinbeck/index.jsp?val=TEACHING_In_Dubious_Battle_Homepage

http://www.democraticunderground.com/discuss/duboard.php?az=view_all&address=367×33561

http://www.flickr.com/photos/usnationalarchives/sets/72157625426044774/

http://www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu/calcultures/ethnic_groups/subtopic3b.html

http://www.oac.cdlib.org/institutions/UC+Berkeley::Bancroft+Library

_________

Peanuts and Oranges: Support Scholarship Fund

For those who have an extra $5 a month for scholarship, the For Chicana/o Studies Foundation was started with money awarded to Rudy Acuña as a result of his successful lawsuit against the University of California at Santa Barbara. The Foundation has given over $60,000 to plaintiffs filing discrimination suits against other universities. However, in the last half dozen years it has shifted its focus, and it has awarded 7-10 scholarships for $750 per award on an annual basis to Chicana/o and Latina/o students at California State University-Northridge (CSUN). The For Chicana/o Studies Foundation is a 501(c) (3) Foundation and all donations are deductible. Although many of its board members are associated with Chicana/o Studies, it is not part of the department. All monies generated go to fund these scholarships.