| Everybody knows about the Fall of Berlin. You Russians will be out in the streets next week doing your Victory Day thing commemorating the capture of the Reichstag, Hitler eating Luger lead, and—on a sadder note—the end of the long, sweet rape-fest Russian soldiers enjoyed on their triumphant march through Prussia.

Yes, their happy thoughts of home and hearth were tempered, as the preachers say, by the realization that their big Woodstock of free, forced love was about to come to an end.

What most people don’t know is that the Red Army had another huge triumph still to come: a crushing strategic victory on a front 3000 miles long, with 1.6 million Soviets annihilating a force that, on paper at least, totaled more than a million battle-hardened Axis troops. I’m talking about Operation August Storm, the Soviet invasion of Japanese-held Manchuria on August 9, 1945—exactly three months after the surrender of the Nazis.

That date is no coincidence. Stalin was a smart shopper, with the gift of timing—if he’d been born a little later and Wester, he would’ve got rich on eBay, gotten into breeding Shih Tsu or something, and all those people wouldn’t have had to die. Anyway, Stalin made a deal with FDR and Churchill at Yalta (Feb. 1945). It was clear by that time that the Germans were finished, and now it was the Americans’ turn to demand a second front to ease their war burden, this one against Japan.

So Stalin signed on the dotted line: he’d invade Japan’s Manchurian colony within three months of the defeat of the Nazis. The deal was, he had to meet that yardstick—it was like one of these NFL contracts with incentive clauses, the ones they do when the draft choice has loads of talent and a massive coke habit. The Big Three, Stalin, FDR and Churchill, were all smiles at the photo ops, but not stupid enough to trust each other. So Churchill and FDR put in a sweetener for their Soviet pals: if the Red Army attacked Japan’s Manchurian colony within three months of the Nazis’ final defeat, the USSR would get permanent occupation of Sakhalin Island, a big long streak of icy forest north of Hokkaido, and the Kuril Islands, a string of fog-bound rocks looping from the North end of Hokkaido to the Southern tip of the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Not exactly Rodeo Drive in terms of valuable real estate, but those places meant a lot to Stalin: they’d been grabbed from the Russians by the Japanese in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05. It was one of those old disgraces that world powers tend to get all obsessive and unhealthy about, like Hitler forcing the French to surrender in the same lousy railroad car where they’d made Germany surrender in 1918. That was what pre-Abba Europe used to be like: never learned anything new, and never, ever forgot a grudge.

There was something kind of poetic-justice about the way the Americans were begging the Soviets to open up a second front against the Japs, because the Russians had been begging the Anglos to open a second front against the Germans for years—two-and-a-half years, actually, counting from Pearl Harbor (Dec. 7, 1941) to D-Day (June 6, 1944).For all that time, the Soviet armies had fought alone against the Wehrmacht, the finest land army since the Mongols. And all that time they were screeching, “Hey Allies, buddies, ol’ pals, how about a LITTLE HELP HERE!”

The Anglos had some pretty good excuses, like the fact that the US was gearing up as fast as it could, passing most of its industrial production directly to its allies while dealing with the Japanese in the Pacific—but to the Soviets, who lost at least 20 million people to the Germans, those years of waiting for the Normandy front to debut seemed like a real long time. I read somewhere that there was a joke making the rounds in wartime Moscow:

Q: What is the definition of an optimist?

A: Someone who believes in a second front.

Pretty lame, joke-wise, but I guess it wasn’t adaptive for Russians to make any really smart jokes while the NKVD was listening. Anybody who got any wittier than Yakov Smirnov was likely to win a free GULAG tour package. And at least the joke makes my point: for Russia, those three years were like trying to hold off a rabid grizzly while your allies kept saying in a cheerful-asshole voice: “Be there in a sec! Just hang in there, think positive!”

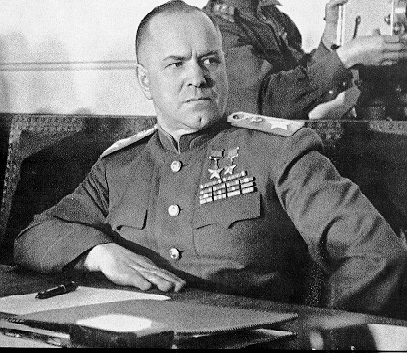

USSR’s Georgy Zhukov

So Stalin had every reason to turn the tables now, let the Americans bleed the Japanese in the Pacific up till the last moment possible, wait until the Imperial forces were a shell, then send in the T-34s. The fact that the Soviet invasion of Manchuria came exactly three months after the fall of Berlin, the maximum time allowed under the Yalta Agreement, might suggest to some of you cynical folks that the generalissimo was biding his time.

But you have to remember, Spring and Summer 1945 was a busy time for all concerned. The Russians were busy rounding up all the surviving Wehrmacht troops and allies (and the Wehrmacht had a lot more allies than anybody wants to talk about these days), maneuvering for position in postwar European power politics, and trying to deal with all the sheer destruction the Germans had visited on Western Russia. The Japanese had to watch their Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere wiped off the map, island chain by island chain. Even on the Home Islands there was a lot more than cherry blossoms falling that Spring. On March 9, the new B-29 Superfortresses dropped incendiary bombs that gutted Tokyo and killed more people, maybe—they’re still not sure but the estimates go up to 200,000—than the A-bombs that fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, just before the Soviets struck Manchuria.

The Japanese had a weirdly passive, almost hopeful attitude toward Stalin anyway, going way back to the early 1930s. Right up to the end, they kept hoping he’d let them alone, or even broker a peace deal that would keep the Americans out of Japan. They were all for fighting to the death against the Yankees, but they kept dreaming that Uncle Joe had a soft spot for them.

Bizarre, but then one thing you notice when you study Imperial Japanese “thought,” if you can even call it that, is that they weren’t much on cold-blooded analysis.

Actually their aversion to fighting the Red Army was a lot more reasonable than most of their other zany ideas. They got it the hard way, by getting crushed in battle against the Red Army in Mongolia back in the late 1930s. Back then there were two factions in the Imperial Japanese forces, the “Northerners” and the “Southerners.” Both sides wanted Japan to go forth and conquer; it was just a question of where. The Northerners shrieked that it was Japan’s destiny to seize Eastern Siberia from the Russians, whereas the “Southerners” wanted to grab SE Asia and the Pacific Islands from the US. Roughly speaking, the Imperial Navy favored the Southern strategy, and the Army favored the Siberian option, for the same reason Bush Sr. used to give for the first Gulf War: jobs, jobs, jobs. The Siberian strategy meant the Army would have the leading role; the Pacific plan would put the Imperial Navy in the driver’s seat.

The Army got its chance to show what it could do in a mainland-Asian war against the Soviets in 1938, with an indecisive bloodbath between Japanese and Russian troops at Khasan Lake. The Imperial Army didn’t take the Russians seriously enough, and they figured that bloody draw was a fluke. One more chance and they’d stomp the Russians like they had in Port Arthur and the Tsushima Straits a generation back. You can’t blame them too much; a couple years later, a guy called Hitler had the same idea about how easy it was going to be to stomp the Russians.

Not these post-Revolution Russians, baby. This wasn’t the Tsars’ clanky old family-mismanaged business, but the Red Army (didn’t switch to “Soviet Army” till 1946). Sure, Stalin had purged the officer corps in the Terror of ‘37, but he was smart enough to keep one very important man alive, even though this guy had once been a Tsarist officer: Georgi Zhukov. I understand there’s a statue of him on horseback in Moscow, and I’d appreciate it if some of you Russian readers would lay a wreath or something by it this weekend on my behalf. I’ll pay you the next time I’m in Moscow, promise. Spa-see-bo, if that’s how you say it.

Zhukov is one of the 20th century’s great commanders. The Russians gave him the same title the Mongols gave Subotai and the Greeks gave Alexander: “the one who never lost a battle.” Weird, but I never heard much about him growing up. I knew who he was, of course, but those Cold-War books were a little stingy handing out praise to Soviet generals. Me, I’m not political. I celebrate Zhukov for what he was, a genius at combined-arms attacks. He reminds me of Alexander more than anybody else, and you can’t get higher praise than that. Too bad he was serving Stalin, sure, just like it’s too bad that magnificent Wehrmacht was serving Hitler. But I still salute the Wehrmacht and I still salute Zhukov. Hey, getting yourself a war to command is even tougher than getting a movie to direct, takes even more capital and cooperation from all kinds of prima donnas. A general’s got to go where the work is, and one thing you can say for those 1930s wacko dictators, they gave the generals plenty of chances to showcase their skill sets. Zhukov is one of the 20th century’s great commanders. The Russians gave him the same title the Mongols gave Subotai and the Greeks gave Alexander: “the one who never lost a battle.” Weird, but I never heard much about him growing up. I knew who he was, of course, but those Cold-War books were a little stingy handing out praise to Soviet generals. Me, I’m not political. I celebrate Zhukov for what he was, a genius at combined-arms attacks. He reminds me of Alexander more than anybody else, and you can’t get higher praise than that. Too bad he was serving Stalin, sure, just like it’s too bad that magnificent Wehrmacht was serving Hitler. But I still salute the Wehrmacht and I still salute Zhukov. Hey, getting yourself a war to command is even tougher than getting a movie to direct, takes even more capital and cooperation from all kinds of prima donnas. A general’s got to go where the work is, and one thing you can say for those 1930s wacko dictators, they gave the generals plenty of chances to showcase their skill sets.

Zhukov, like a lot of the great 20th century commanders, started out as a cavalry officer. Not a great career choice in most parts of the world in the early 20th-century, but in the Russian Civil War, where Zhukov played his rookie season, cavalry was still important—lot of ground to cover, mostly flatland, no roads worth mentioning. The machine gun and barbed wire looked like they were finishing off cavalry forever on the Western Front during WWI, but a few smart horse officers realized that you could use these tank thingies not just as screens for infantry advance but as bulletproof cavalry, doing the same old dashing advances J.E.B. Stuart would have recommended. The only difference was in logistics: the new cavalry advance had to be a way more carefully prepared business than the old saber charge, with logistics assuming a huge role.

When Zhukov assumed command of the Soviet forces in Mongolia (June 1939), there’d already been two months of straggling border skirmishing, escalating from a proxy fight between the Russians’ Mongolian allies and the Japanese’s Manchurians, to full-scale armored engagements between the Japanese and the Red Army.

What Zhukov did way back in 1939 set the pattern not just for the Red Army’s successes against the Germans but for that final, perfect campaign against Japan in Manchuria in 1945. First, Zhukov dealt with his logistical problems, something the Japanese were too mystical and transcendental to take seriously. Next, he made sure all arms were in total coordination: air force, armor, infantry, artillery. That was another thing the Imperial Japanese were too snotty and quarrelsome to do: from 1919 to 1945, one of the constants in Japanese conduct in Manchuria is that the services hated each other, fought among each other all the time. In 1945 that meant that the Navy refused to lift a hand to help stranded Japanese troops evacuate the Asian mainland; back in 1939, it meant that when the Japanese air force launched a successful attack on Soviet airfields in Mongolia, jealous local commanders ordered their pilots to halt all attacks.

In August 1939—you Russians must like hot weather, you seem to do a lot of your big attacks in August—Zhukov had all his ducks in a row, and gave the word to attack. Remember, attacking wasn’t something most commanders in 1939 did easily. They’d learned in 1914-1918 that the advantage was with the defenders. Only a few guys like Patton, Rommel, de Gaulle and Zhukov realized that that wasn’t necessarily so any more. Zhukov showed how it was done by encircling and annihilating the Imperial Japanese forces in Eastern Mongolia. And I do mean annihilating, because as usual, Japanese troops just didn’t surrender, so after Zhukov’s pincer attack surrounded them and they’d turned down a trip to the GULAG, Soviet artillery wiped them out.

|

Zhukov crippled Japan’s Imperial Army, much as this photo-caption is crippled with tasteless irony. |

Another little preview of 1945 during this battle was the way Japanese troops dealt with the inevitable, as in “total denial,” aka: “brave but stupid.” One Japanese officer supposedly led his men on foot in an attack against Soviet tanks, with his Samurai sword on high. That was a pattern you were going to see again and again, in Saipan, Okinawa, the Philippines, everywhere Japanese troops were defeated: they thought way too much of arranging glorious deaths for themselves, and not nearly enough about arranging the same thing for the enemy.

But this time, in a rare moment of reason, the Imperial Armed Forces learned their lesson: after meeting Zhukov and getting slaughtered next to that frozen Mongolian river, they lost all appetite for a land war against the Soviets. Now, the Japanese were all for headin’ south, to the sea and sun, to those balmy Pacific beaches, starting with Pearl Harbor.

That little shift in Japan’s business expansion plan kept them pretty busy. So now we can fast-forward all the way to 1945 without losing much, because while the whole rest of the world was exploding, in the meantime, the USSR-Japanese borders in Manchuria/Siberia didn’t so much as flicker from 1939 to 1945. Nothing, zip, nada going on for all that time. Stalin kept 40 divisions there (remember, a Soviet division was only 11,000 troops), but thanks to Richard Sorge’s Tokyo spy ring, he knew the Japanese weren’t interested in another big fight in Manchuria, which made planning for the German front a lot easier.

So now it’s May 1945: “Hey Comrade Stalin, you’ve just won the Super Bowl! Where are you going?” Well, it wasn’t Disneyland; “I’m goin’ to Manchuria!”

And like I said earlier, he was in no hurry to get there, because every day the Japanese were weaker. The B-29s ran the Tokyo route more often than commuter flights from SFO to LAX. The last of the island fortresses were falling—and instead of reinforcing the Manchurian Front, the Japanese Imperial Command, in its usual psychotic state of total denial about the Soviet threat, was actually sucking every decent infantry and armor unit away from the Kwantung Army in Manchuria and feeding them into the hopeless war against the US advance toward the Home Islands.

I came across an amazing story of this one cool Japanese officer who was caught in that transfer. Actually, there are a lot of amazing stories in this Manchurian campaign, but this guy is a classic: Takeichi Nishi, also known as “Baron Nishi” when he used to hang out with the stars in Beverly Hills. Nishi was a child of the Japanese elite, a nobleman and a famous Olympic horse-riding star, and he spent a lot of pre-war time going to snooty horse-riding tournaments in Hollywood, driving his convertible around waving to all those silent-movie stars.

He was also a cavalry officer in the Imperial forces, which wasn’t so much fun, especially when his unit was transferred from Manchuria to Iwo Jima in 1944. His unit didn’t even make it to Iwo: they were torpedoed en route and all their tanks are still rusting somewhere on the Pacific sea floor, condos for the hagfish. Nishi and his men survived the sinking, all but two of them, and made it to Iwo Jima, even got new tanks. But they were ordered to bury them up to the turrets. Not much chance for maneuver warfare; this was going to be one of those suicide stands Showa-era Japan loved so much.

The Americans were all for that, usually: “Here, we’ll hold the bayonet and you run onto it!” but—and I have to admit, this is kind of touching even for me—they knew that their old Hollywood buddy “Baron Nishi” was on the island and they didn’t want to hurt him. So they actually sent guys with bullhorns around the island saying, “Paging Baron Nishi, paging Baron Nishi! Please surrender at the front desk, you can have your horse back and everything! Free tickets to the new Clark Gable flick! C’mon, don’t be a sore loser!” But the dude was an Imperial Japanese officer; they weren’t always smart but they were hardly ever chickenshit. Eventually they found him: crisped by a flamethrower, still wearing his riding boots.

So that, in a crispy-fried nutshell, is what happened to the best units of the Kwantung Army while it waited with its head down in bunkers all along the 2000-mile front facing the Red Army: all its best troops were gone, dead in pointless outpost defenses, and all its armor was gone. The Soviets were going to have a wonderful time of it. They were going to do this like a victory lap, a tour de force, a training video.

This was a campaign between two great empires—both gone now, it occurs to me—but one, the Soviet, was at the absolute top of its game, and the other, Imperial Japan, was dying and insane. There were still about 700,000 Japanese and Korean troops holding the line in Manchuria, but they weren’t exactly Samurai-quality. A full 25% of the Kwantung Army’s strength was guys who’d been drafted in the two weeks preceding the Soviet attack. We’re talking about an army that looked like John Bell Hood at Atlanta, missing an arm and a leg and not top-drawer material to start with. The amazing thing is that the Japanese troops knew it themselves. They were the dregs, dragged out of junior-high classrooms and old-age homes and shelters for the hopelessly useless, and they called themselves names that sound like a Heavy Metal amateur night at your local bar: “human bullets,” “Manchurian orphans,” “Victim Units” and “The Pulverized.” (If you don’t believe me, check out Philip Jowett’s book,The Japanese Army 1931-1945, page 22.) Their official strength was 24 divisions, but that translated to about eight divisions of effectives, with only about 1200 light armored vehicles.

Against that was a force that God would have made excuses to avoid facing in the Octagon: 1,600,000 battle-hardened Soviet troops with 28,000 artillery tubes and 5000 tanks—and more than 3000 of those were T-34s, the best tank in the world at that time. (You tank nuts who disagree with that assessment can send me all the King Tiger sites you want; it was a nice blueprint but they tried it against the T-34s and it LOST, and I kinda go by success in battle, not bluebook-style stats.)

The Red Army had learned a lot about logistics since 1941, and some of the moves they made to prepare for the assault on Manchuria were pretty amazing. Instead of trying to transfer thousands of tanks across the whole Eurasian landmass from Eastern Europe to Manchuria, the Russian armored units like the 6th Guards Army, one of Zhukov’s best, left their tanks in Czechoslovakia before the engines even had time to cool down, hopped into troop trains and crossed the continent to meet up with fresh new tanks, shipped from factories east of the Urals, when they arrived on the Manchurian front. By August 1945, the Russian supply lines were running so smoothly that they could ship pretty much anything anywhere it was needed. Like Soviet armies always did, they took logistics and surprise both dead seriously, so they ran up to 30 trains a day across Asia, but I should say “a night,” because to keep tactical surprise they ran all those trains at night. (If you want a great detailed account of the prep the Soviets took, read Col. David Glantz’s book The Soviet Strategic Offensive in Manchuria, 1945.)

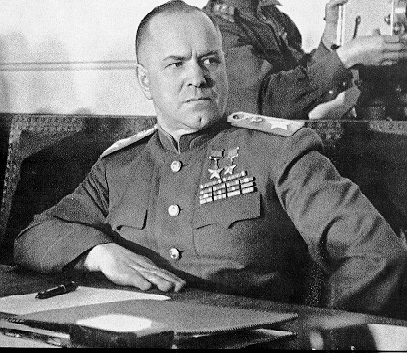

Erwin Rommel—A great military commander, but, like Robert E Lee, his tragedy is that he served an evil regime.

The combination of logistical superiority and tactical surprise gave the Red Army commanders a lot of flexibility when they looked at the maps of Japanese-held Manchuria. First, a little geography: Manchuria is sort of like a box, with high mountains and big rivers along the borders, sloping down to flatland in the middle. The middle part of the province was the prize; that’s where the fertile land, the population and the industry was concentrated. Most of the Japanese defensive forces were concentrated on the east side of the box, where they faced off against the Soviets along a north-south line following the Ussuri River from Khabarovsk down to Vladivostok.

The Kwantung Army commanders expected the Russian push to come from the east, and what defenses they had were concentrated there, especially around a town called Mudanjiang—tiny place by Chinese standards, only three million people in it even today.

The whole western border, butting up against Mongolia, was left all but undefended. To attack from that direction you’d have to cross the Gobi Desert, which the Japanese considered impossible, then go over the Khingan Mountains, which hit about 5500 feet and are what BLM would proudly call a “roadless area.” The whole western border, butting up against Mongolia, was left all but undefended. To attack from that direction you’d have to cross the Gobi Desert, which the Japanese considered impossible, then go over the Khingan Mountains, which hit about 5500 feet and are what BLM would proudly call a “roadless area.”

So if you’ve read any military history you can guess where the Soviets put their biggest forces: yup, due west, ready to storm across the Khingan Mountains. Of course this put a huge strain on their supply lines, but that was nothing for a force as tough and experienced as these dudes.

Oh, that wasn’t their only attack front. In fact, they attacked everywhere. Like I said, when you study this campaign you get the sense that the Red Army was putting on a show, doing a demonstration of Suvorov’s old line, “Train hard, fight easy.” They’d sure trained hard, and lost a whole generation doing it; but the survivors seemed like they were almost having fun with it, running a clinic.

On August 9, just in time to claim Comrade Stalin’s prizes (Sakhalin Island, the Kurils, Korea), the conductor waved his baton and the whole magnificent slaughter ballet started up. They attacked EVERYWHERE. They attacked from the southwest, right across the Gobi, and one column even came up through Kalgan, in rock-throwing distance of Peking (hey, it was still Peking back then). They rushed south from Khabarovsk, and west from Vladivostok. That was the one place they ran into trouble, at that little town of Mudanjiang, where the Japanese had dug in like gophers expecting the Rapture. The Red Army had 11,000 casualties, one third of its total for the whole campaign, in the attack on Mudanjiang.

I mean, it was like they were showing off. They dropped paratroopers on Harbin, the big prize, in the dead center of the Manchurian plain, and other parachute units on Mukden. Best of all, they dropped in on Port Arthur and Darien, site of Russia’s big humiliation in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-5.

Everything went right. It’s too bad we’re too stubborn to give a little appreciation to ex-enemies, because if people knew more about this campaign they’d enjoy the Hell out of it, just for the sheer beauty of the plan and execution.

Like all advances that work better than they’re supposed to, this one stalled because it literally ran out of fuel. Those T-34s got so far inside Kwantung Army lines in the first few days that the Soviet Air Force had to use DC-3s to bring in gas. By that time, it was pretty clear that the cannon fodder the Japanese had left to man the trenches had had enough, so the problem wasn’t so much defeating the Axis forces as beating the American naval task forces down to the Korean Peninsula, the one big strategic objective the Red Army hadn’t yet overrun. They made it about halfway down the Peninsula, and then had to stop because a US force had made a landing at Inchon—yup, the same Inchon that MacArthur was going to make famous a few years later. That’s how the Korean Peninsula came to be divvied up halfway down, like an Xtreme circumcision: because that’s as far as the Red Army’s tanks got before the US Navy’s landing crafts started unloading the USMC. We were still “allies,” of course, but we were already the kind of allies who playfully go for the carving knives when there’s a piece of chicken still on the table, chuckling all the way. Or as Pol Pot said of the Vietnamese in the early 70s, “Friends, but friends with a conflict.”

The Red Army still had jobs to do, because Stalin’s armies were always about more than just conquest. For one thing, they had to dismantle the whole industrial infrastructure of Manchuria—pretty considerable, too—and ship it back to the USSR “for safekeeping.” Then they had to corral the 600,000 surviving soldiers of the Kwantung Army. Most resistance was over by August 14, 1945, but a few units held out longer, until the Emperor’s surrender broadcast—which most of the Japanese alive in 1945 still remember as the most crushing event in their lives—filtered down to the bunkers and foxholes all along that 3000-mile front. When they were all rounded up—well, this IS Stalin we’re talking about, so you can’t get too sentimental; what do you think he did with them? Nah, didn’t kill ’em—too wasteful. Instead all 600,000 Japanese POWs were herded into cattle cars, the cars were boarded up, and the whole of what used to be Imperial Japan’s proudest army ended up in freezing prison camps.

I know a lot about what happened to these guys, and you can too, if you read this amazing site I came across called “The Notes of Japanese Soldier in USSR”:

I read it in the English version (you can get it in Russian and Japanese too), kind of badly translated but illustrated with these great drawings made by one of the “Pulverized” Kwantung Army POWs, who was shipped all over the Soviet empire, and ended up in Hungary riding horses with Mongolian POWs. The best thing about his story and his illustrations is that they’re about the happiest things you’ll ever see. The good old Japanese sense of humor is all over the place: jokes about baseballs smashing into the catcher’s nose in a POW-camp pickup game, jokes about “unfunny injections” from gorgeous Russian-lady doctors (the dude can draw women, let me tell you) and jokes about the fun of dying of dysentery in the Russian winter. It’s amazing. You expect some gloomy Solzhenitsyn shit and you get like Tom Sawyer in the GULAG. I can’t remember when I’ve enjoyed reading anything as much as I did this site.

But as much as I love the Imperial Japanese forces, I have to do my job here as the War Nerd and say the final lesson I take away from all the research I’ve been doing. For awhile now, I’ve been saying that the two great Axis powers had the finest soldiers of that war. Well, I was wrong. I’d say the Japanese may have had the bravest soldiers, but that’s not the same thing as “best.” Like the Lt. who charged those Soviet tanks on foot, with a sword; brave, but stupid and a waste of fine troops. Better to scatter and hope some of your men reach base than walk into machine guns like that.

When all’s said and done, I have to say, and it’s kind of sad, the Russians and the Germans divide first place between them—the Wehrmacht and the Red Army, tied for first and, unfortunately, locked in a death grip. Nobody else comes close. Third, a distant third, to the US; fourth—who even cares? The rest don’t even count. All creds, props, whatever to you Russians, and though you might not like me saying it, to those Germans too, because you two were Ali and Frazier, man. You were the twin towers, the best of the best. So bask in that; your grandparents earned it. Glug some vodka for me and pour a Roman-style libation at the foot of Zhukov’s statue for me…comrades.

Gary Brecher’s book The War Nerd is now available on Amazon and other bookstores.

|

Zhukov is one of the 20th century’s great commanders. The Russians gave him the same title the Mongols gave Subotai and the Greeks gave Alexander: “the one who never lost a battle.” Weird, but I never heard much about him growing up. I knew who he was, of course, but those Cold-War books were a little stingy handing out praise to Soviet generals. Me, I’m not political. I celebrate Zhukov for what he was, a genius at combined-arms attacks. He reminds me of Alexander more than anybody else, and you can’t get higher praise than that. Too bad he was serving Stalin, sure, just like it’s too bad that magnificent Wehrmacht was serving Hitler. But I still salute the Wehrmacht and I still salute Zhukov. Hey, getting yourself a war to command is even tougher than getting a movie to direct, takes even more capital and cooperation from all kinds of prima donnas. A general’s got to go where the work is, and one thing you can say for those 1930s wacko dictators, they gave the generals plenty of chances to showcase their skill sets.

Zhukov is one of the 20th century’s great commanders. The Russians gave him the same title the Mongols gave Subotai and the Greeks gave Alexander: “the one who never lost a battle.” Weird, but I never heard much about him growing up. I knew who he was, of course, but those Cold-War books were a little stingy handing out praise to Soviet generals. Me, I’m not political. I celebrate Zhukov for what he was, a genius at combined-arms attacks. He reminds me of Alexander more than anybody else, and you can’t get higher praise than that. Too bad he was serving Stalin, sure, just like it’s too bad that magnificent Wehrmacht was serving Hitler. But I still salute the Wehrmacht and I still salute Zhukov. Hey, getting yourself a war to command is even tougher than getting a movie to direct, takes even more capital and cooperation from all kinds of prima donnas. A general’s got to go where the work is, and one thing you can say for those 1930s wacko dictators, they gave the generals plenty of chances to showcase their skill sets.

The whole western border, butting up against Mongolia, was left all but undefended. To attack from that direction you’d have to cross the Gobi Desert, which the Japanese considered impossible, then go over the Khingan Mountains, which hit about 5500 feet and are what BLM would proudly call a “roadless area.”

The whole western border, butting up against Mongolia, was left all but undefended. To attack from that direction you’d have to cross the Gobi Desert, which the Japanese considered impossible, then go over the Khingan Mountains, which hit about 5500 feet and are what BLM would proudly call a “roadless area.”