Cairo

Instead of passion and hope, all there is left on the streets of Cairo is depressing defeatism, frustration and hate.

Once there were heads and hands raised high, and the Egyptian flags flew proudly in the wind; there were fiery speeches, dreams of social justice, of a brand new country with an enormous heart and a distinct place for every citizen. Once it all was not unlike what has been taking place all over Latin America for more than a decade.

But it now appears to be over, burned down and in ruins. These days it is hate that has replaced hope, and there is so much of it, so much hate, all over the capital and all over the country!

And it is not a healthy, constructive hate pointed at savage capitalism or imperialism. It is a depressing hate, a defeatist hate; a hate that Egyptians are now showing towards each other. There is hardly any ideology left, except in the ranks of the Socialist Revolutionary Organization, and very few other groups and movements that are still fighting for the essential values of the 2011 Arab Spring.

There is still a core, a skeleton of the “Movement of the 6th Of April” – the organization that stood at the vanguard of the Revolution. But even that suddenly appears to be too weak – not strong enough to halt this depressing reverse trend.

As I look down from the bridge at Bulak neighborhood, the citizens are engaged at finder-pointing and loud shouting. Men and women are insulting each other, and soon there are skirmishes and fistfights. This is some sort of local-level settling of scores between the supporters of The Muslim Brotherhood and the followers of the military – that very same military which overthrew the moderate but inept Islamic government in July 2013.

Soon I am spotted and several fists are raised towards me, fingers pointed. One minute later, stones are flying my way.

“Get into the car!” My Egyptian friend shouts at me. “Get inside! If even one person attacks you, the crowd will get here in no time and they will take you apart… They will kill you.”

“But why?” I wonder naively.

“These days they don’t need any reason”, he explains. “They hate foreigners. They hate each other. Don’t you see what is happening in my country?”

I see. And what I observe, I don’t like at all. The hope is over. What is left is a terrible hangover and a bad, dark mood.

But many rich urban dwellers are trying to convince each other that things will get better soon. The upper and upper-middle classes are openly supporting the military, not unlike in Chile, after the 9-11-1973 military coup’ d’état in which the pro-Western faction of the army led by General Augusto Pinochet overthrew the progressive government of Salvador Allende.

Of course the Egyptian Islamist President Morsi and his Muslim Brotherhood had nothing in common with la Unidad Popular, but the willingness of the elites in the two countries to back the Western-supported military, is truly striking and revealing.

***

As I am photographing the ruined headquarters of the Muslim Brotherhood in Cairo, a black limousine stops, the back window is open, and the upper class-looking woman begins shouting at me: “Morsi was a criminal! And I am forbidding you to photograph this building!”

“Who are you?” I wonder. “Do you have any authority to forgive anything, in this public place?”

“I am an Egyptian woman!” She spits at me with scorn.

“That is great”, I say. “But I still don’t understand what gives you the authority to prevent me from working?”

She begins calling someone frantically on her mobile phone. She is obviously reporting me, asking for reinforcements in her sacred fight against a dangerous foreign element.

“There is so much fear”, my friend, a psychiatrist Mohammad Shafik, told me. “I love photography, but these days I don’t even dare to take pictures of scenic spots in and around my own city – Cairo.”

There is clearly something wrong with Cairo’s residents. As supporters of General Sissi exchange punches with supporters of Morsi and his Muslim Brotherhood, women are running around and shouting frantically. Nile Street is blocked, as there is yet another bomb threat. Four people have already been killed recently, not far from here.

Vigilantes are controlling traffic. It looks like a state of siege in front of Sadat’s old palace; there are tanks and sandbags everywhere, the military and police are pointing guns in all directions.

It is 6th October, Victory Day in Egypt, the day when, 40 years ago, the Egyptian military recaptured the Sinai Peninsula from Israel. Here it is known as the October War, or as the Yom Kippur War in Israel.

In 2013, this anniversary is the moment to show support for the Egyptian army apparatus. Never mind that the Egyptian armed forces have been getting 1.3 billion dollars annually from the United States. Never mind that for years and decades, it had been backing the brutal pro-Western regime of Mubarak. No matter that now it was clearly getting back into power.

“Prophet Mohammed said that the Egyptian army is the best in the region”, reads one of the posters.

Even as the people are cheering the army, the canons on top of the armored vehicles point suspiciously at the crowd. Tanks are blocking all the streets leading to Tahrir Square. F-16 fighter jets are flying over the capital, and so are combat Apache helicopters.

There are slums are all over the capital, and more than 70% of the people of Cairo live in misery, as a sociologist Maher Abdelmalek tells me. But the misery is, suddenly, not on the agenda of either side. It is not discussed and it is not what people are fighting against.

I go to the slums and photograph there, but another set of vigilantes tries to prevent me from working. The same in Giza, where I attempt to film the clogged waterways.

There are insults and more insults, and there are threats. To be a foreign correspondent or a filmmaker working in Cairo, feels much more dangerous than working in DR Congo or in any other war zone.

***

Bombs go off at regular intervals. People are dying. The military has already murdered perhaps 2,000 people since the coup, but the numbers are not confirmed or trustworthy, and are most likely much higher.

Fear is now so potent that even members of the revolutionary movements and organizations do not dare to meet each other during the day, or at night. Several of my encounters are cancelled, despite the fact that I am not working for any Western media outlets – I am making a film for the Venezuelan television network “TeleSur”, and reporting for RT and CounterPunch.

Nobody trusts anybody. Two of my main contacts are in hiding somewhere in the countryside. Members of several allied parties are now refusing to communicate with each other. It is impossible to plan anything, as all trust is broken and fear reigns over the capital.

But ask the elites and they will tell you that everything is great. I ask the General Manager of one of the major luxury hotel chains, whether things have really improved after the coup.

“What coup?” he looks at me in bewilderment. Then he gives me a big smile: “Oh, you mean after Egypt got liberated? Now things are fantastic! And they will soon get even better… Much better.”

My driver laughs when I tell him that Egypt is doing well. He tells me about inflation and about him leaving his teaching position at a public school and becoming a driver: “I couldn’t pay tuition for my two sons.”

We drive to Giza, to the Pyramids, just to see what I had already suspected. The entire area is empty and there are only touts in front of the Sphinx. I see only one tourist bus, with somehow lost looking and confused Spanish visitors. And there are rumors of serious looting. The tourist industry has basically collapsed, but this is also not discussed openly, it is totally hidden. An insurgency is flaring in Cairo, in the Suez area, Alexandria, even in the Sinai Peninsula, which is the main center of the Egyptian tourist industry.

By 2:30PM on the 6th October, there is fighting all over the capital. But fighting is also not called fighting here. These are ‘incidents’, and there are some instances of ‘terrorism’. ‘Public order is being disrupted’. Again, the terminology is similar to that used in Chile in and after 1973, or in Indonesia after 1965. Except that in Chile, the great majority of the people had been aware of the situation and of cynical lies.

***

Clouds of teargas hang over the city. Once in a while, explosions resonate, from various directions.

The situation is becoming extremely confusing. There is so much shouting and so little information. I ask my driver to turn on the radio, but all we can hear are some militaristic and patriotic songs.

But everyone is aware of what will be happening after 15:30, when the Muslim Brotherhood cadres begin leaving their mosques.

It all looks grotesque: little children and women holding photographs of high army officials, even kissing their portraits for the cameras; the military pointing their cannons at civilians, as they have been doing for decades… They are aiming even at those who adore them.

Then some people begin to charge and the teargas canisters start exploding. There are several rounds of live ammunition fired into the air.

At 15:30, exactly as expected, the Muslim Brotherhood joins those Sinai celebrations, in its own – in its predictably heavy-handed way.

The battle begins. I see people climbing the walls, holding children to their chests. I see hard-core Islamists with green ribbons encircling their heads, slings in their hands. I see the armed forces charging, and shooting. I see people falling. Not for the Revolution, not for social justice, not for a better Egypt. I see people dying, on both sides, out of spite, from hate. I see human lives wasted. And I see the end of the Arab Spring nearing.

Battles on the 4th.

Brotherhood in Action at the side streets.

Celebrating Sinai.

Egyptian upper class family.

Hate in the streets.

How the how majority lives.

In front of the National Museum.

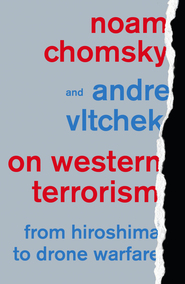

Andre Vltchek is a novelist, filmmaker and investigative journalist. He covered wars and conflicts in dozens of countries. His discussion with Noam Chomsky On Western Terrorism is now going to print. His critically acclaimed political novel Point of No Return is now re-edited and available. Oceania is his book on Western imperialism in South Pacific. His provocative book about post-Suharto Indonesia and market-fundamentalist model is called “Indonesia – The Archipelago of Fear”. He just completed feature documentary “Rwanda Gambit” about Rwandan history and the plunder of DR Congo. After living for many years in Latin America and Oceania, Vltchek presently resides and works in East Asia and Africa. He can be reached through his website or his Twitter.