Liberace: an affair to remember

Behind the Candelabra

An HBO production

The high camp of Behind the Candelabra conceals an old-fashioned love story, Duncan Wu writes

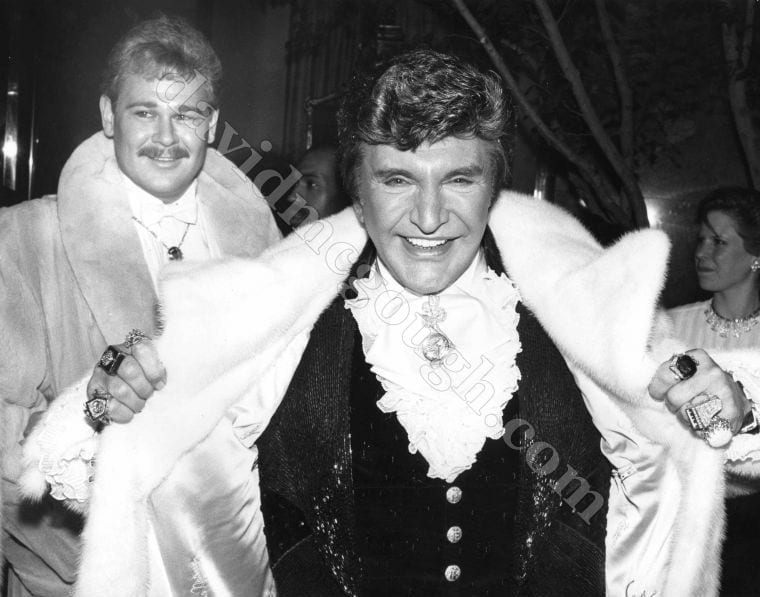

SOURCE: HBO FILMS

y Duncan Wu, Times Higher Education

Pink narcissus: as Scott Thorson discovers, the inevitable concomitant of Liberace’s self-love is his need to possess

Behind the Candelabra

Directed by Steven Soderbergh

Starring Michael Douglas and Matt Damon

Released in the UK on 7 June

I call this palatial kitsch,” Liberace (Michael Douglas) says to his new “secretary” Scott Thorson (Matt Damon) as they tour his mansion. “These are actual Roman columns! Ionic.”

There is as much self-awareness as wit in such remarks – which exemplify Liberace’s brand of camp. “Stare as long as you like,” Liberace declares while parading his sequinned tux in front of a Vegas audience. “You paid for it!” But then, what is camp if not self-aware?

“Oh my God!” screams Liberace while watching a porno film. “How does he get that whole thing down his throat? It’s bigger than his head!”

“It’s a freak show,” replies Thorson. The campest thing about Behind the Candelabra is that it teases out its subject’s potential as freak show and works brilliantly on that level, as all films that take us down rabbit holes should do.

To watch it is to enter a universe in which Liberace’s limp-wristed houseboy Carlucci (amusingly played by Bruce Ramsay) “rules the roost”, which is filled with hunky young men with names such as Billy Leatherwood wearing white bejewelled mankinis, mink trenchcoats or fur stoles so lengthy they require their own car and chauffeur. “Pig?” Carlucci says to Thorson when they first meet, as he holds out a tray of nibbles. “Pig in a blanket?” Which is exactly what Thorson will become.

[pullquote]‘Too much of a good thing…is wonderful!’[/pullquote]

Its outlandishness tips us off to the fact that, like most films about the rich and famous, Behind the Candelabra is voyeuristic and its visual style is manicured accordingly. The camera glides through the rooms of Liberace’s Vegas mansion, lingering on the gold lamé drapes, lurid soft furnishings and bulging crotches of the louche, blond young men sprawled on them. Yet its perspective is that of the outsider – doubly so, in view of the fact that its two protagonists are played by heterosexuals.

________________________________________________________________________

SIDEBAR

The Ugly Behind the Glitter

A man not terribly given to self-flagellating introspection when it came to personal ethics, Liberace was a good example of a slowly- dying world, the America of a thousand myths and thousand dreams, the blessed land of I Love Lucy and Leave it to Beaver and simpletonia that began to crumble after Eisenhower was gone and the Vietnam war injected the first doubts about our supposedly morally immaculate nature. It’s been a very protracted death.

Of course that was also the world in which meat eating, trophy hunting, wearing furs and other banal atrocities against animals were regarded as unquestionable, a human’s inherent birthright of unlimited dominion over “the other” by dint of ancestral sacred decrees. Animal rights did not exist as such, only mild forms of animal welfarism. Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation did not burst on the scene until 1975, although other equally formidable arguments on behalf of non-human beings would soon follow, some, like Tom Regan’s, tackling the even more theoretically demanding question of “animal rights”,

This cloying innocence that seemed to envelope so much of the American mind (and whose remnants still collect so much suffering) is however no valid refuge from excessive insensitivity for the sake of pure and unadulterated hedonism, which Liberace raised to industrial dimensions, indeed made it an integral part of his professional persona (for which he dutifully claimed tax deductions). His flamboyant fur coats, often made of endangered animal pelts (one had cost the lives of more than 150 arctic foxes), underscored the sheer conventionality of his mind since he was also a well-known solicitous pet lover.

An unrepentant self-absorbed decadent —devout Catholic by own admission—”Lee”, as his intimates called him, naturally harbored a pronounced dislike for all forms of socialism. In the manner of most once-poor self-made men, he despised “malcontents” and thought capitalism was simply peachy. And the more the better. As the HBO film reminds us, he thought Jane Fonda and Ed Asner were way out of line, were abusing their fame by being outspoken against the (Vietnam) War.

In contrast to his flamboyant stage presence, Liberace was a conservative in his politics and faith, eschewing dissidents and rebels. He believed fervently in capitalism and was also fascinated with royalty, ceremony, and luxury. He loved to hobnob with the rich and famous, acting as starstruck with presidents and kings as his fans behaved with him. Yet to his fans, he was still one of them, a Midwesterner who had earned his success through hard work—and who invited them to enjoy it with him.[25]

Rotten as the world is today with its media-abetted, sick fascination with celebrities, and slavish admiration for wealth and power, it’s unlikely we will see the emergence of another Liberace. Perhaps the closest we can muster is a bloated Donald Trump. And that’s more than enough.

— Patrice Greanville

_________________________________________________________________

(Main body of article continues here)

And that gives me pause: is the casting of two actors alien to the culture of which they must pretend to be habitués a failure of nerve or a canny business decision? Perhaps both, but clearly the film’s producers won’t lament the fact that with Damon and Douglas, audiences are unlikely to be deterred by scenes of snogging, soaking in the hot tub and post-coital grooming.

According to its director Steven Soderbergh, Behind the Candelabra failed to secure funding from major Hollywood studios because it was considered “too gay”, prompting its producers to turn to a cable television station, HBO. Having been transmitted in the US, it now receives a theatrical release in the UK. (Given the choice, I would prefer to see it on the big screen.) HBO is aware its stars will attract a sizeable audience but that would mean nothing were they unable to give life to the drama. As it happens, Damon and Douglas are completely persuasive as two characters drawn into a hopeless affair – although it has to be said that the film as a whole cannot help succumbing to the temptation of depicting homosexuals as psychological cripples.

“Why do I love you?” Liberace remarked famously in his cabaret act. “I love you not only for what you are but for what I am when I am with you. I love you not only for what you have made of yourself but for what you are making of me.” As Douglas intones this sick-making tosh, the camera gazes at Damon’s ringed fingers and chauffeur’s uniform, which are designed to complement Liberace’s sparking tuxedo. It is the beginning of their relationship and there is a sense of the characters beginning to merge, an impression cultivated by the intercutting of the stage act (of which Thorson was part) with them having sex.

SOURCE: HBO FILMS

Excess passion: ‘I can’t stand it when you have a face like that. Especially when I’ve paid for it!’

“Oh my Christ, I look like my father in drag!” Liberace says as he watches himself on television. He is too in love with himself not to resort to plastic surgery.

“I would say a full facelift, with silicone implants to prevent the return of lines round the mouth,” says the creepy, whisky-drinking Dr Jack Startz (Rob Lowe), his face locked in a permanent rictus thanks to numerous botched surgeries. “My feeling? Why go through the money and the work just to have it all fall down within a year?”

Some of the film’s funniest scenes concern the facelift. Immediately prior to his operation, Liberace removes his toupee, complaining: “I just do not understand why I can’t keep my hair on during the procedure!” And afterwards, when he has healed, he asks Dr Startz: “Will I ever be able to close my eyes?” (The answer is “no”.)

The least attentive witness to his own emotional needs, Liberace perceives Thorson’s love like the narcissist he is, reciprocating with the demand that Dr Startz “make Scott look like me”.

“I guess I should be flattered,” Thorson tells a mutual friend. “But won’t it be weird? Looking in a mirror and not recognising myself?”

It is a sharp piece of dialogue, because submission to Liberace’s impulse can only lead to dissolution of Thorson’s own identity. And before he knows it he is hideously overweight, snorting lines of coke in gay movie theatres, looking fruitlessly for his lover in the dark and throwing up.

The inevitable concomitant of Liberace’s narcissism is his frustrated desire to possess. “I can’t stand it when you have a face like that,” Liberace says during one of their tiffs. “Especially when I’ve paid for it!” He wants to control Thorson’s moods and his inability to do so dooms their relationship. As in other films about failed affairs, the best lines come in the third act. “I have an eye for new and refreshing talent,” Liberace says. “You have an eye for new and refreshing dick,” Thorson replies.

“I don’t want to be remembered as some old queen who died of Aids,” the ailing Liberace is made to say on his deathbed. And one reading of Behind the Candelabra would be as a tale of damnation. It has nothing to say about his promiscuity, however: its criticism is directed at other things, such as Liberace’s view that the point of life is “to entertain the world and to sell drinks and souvenirs”. (His contempt for Jane Fonda’s pursuit of “causes” is not something with which the film has any sympathy.)

Behind the Candelabra is honest, too, about Liberace’s ruthlessness: when finished with Thorson he pays him off and legally restrains him from speaking publicly about their relationship – as he did with his predecessors.

But this is not Liberace’s film, it’s about Scott Thorson and his eventual understanding that to have loved someone, however disastrous the outcome, is better than not to have loved at all. “He’s my whole world,” it has him say as the relationship falls apart, “he’s better than a father. Nobody ever took care of me the way he did.” All of which makes this a full- bloodedly romantic and quite old-fashioned story.

Soderbergh’s films can suffer from glibness, but not this one. For one thing, it has the ability to laugh at itself, and not in a way that diminishes its characters. Best of all, its final scene defies the tyranny of naturalism to offer an apotheosis seen within Thorson’s imagination, in which Liberace is allowed to say what seems most faithful to his unrepentantly hedonistic nature: “Too much of a good thing…is wonderful!” Those undeterred by men who wear eyeliner will find Behind the Candelabra an enjoyable combination of glitz and silliness, with a truthful and compelling drama at its heart.

PRINT HEADLINE:

Article originally published as: ‘Too much of a good thing…is wonderful!’ (6 June 2013)

AUTHOR:

Duncan Wu is professor of English, Georgetown University.