“The focus of the restructuring of the economic system … is to allow the market [forces] to play a ‘decisive role’ in the allocation of resources.”

That’s it? The whole world was breathlessly waiting – and this is what the world got: an enigma enveloped in a riddle inside a Chinese box, in the form of a cryptic communique issued by the long-awaited Third Plenum of the 18th Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s Central Committee.

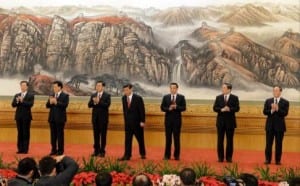

To know who is ultimately responsible for this – the first serious policy blueprint unveiled by the new Chinese leadership of President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang – one just needs a glimpse at the photo: these are the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee, the men who really rule China.

And what’s at stake could not be more serious; no less than the strategic choices addressing China’s inevitable ascension to the status of world’s number one economy.

One should always remember how the CCP works. The Plenum was supposed to “forge consensus” among the CCP elite and set the tone for the next stage of China’s breakneck development.

And yet anti-climax seems to have become the operative concept here. The media frenzy in China, pre-Plenum, had been relentless – of a “change we can believe in” variety (no, nothing to do with American-style billion-dollar political campaigns). After all, the number 4 in the Politburo Standing Committee, Yu Zhengsheng, had publicly promised “unprecedented” reforms, leading to a “profound transformation in the economy, society and other spheres”.

The frenzy was mostly generated by a reform road map published by the State Council’s Development Research Centre – the so-called “383 plan”. In trademark Chinese numerology, the road map delineated the “three-in-one train of thought, the eight key areas and the three projects of reform”. The secret of a successful reform would be “the proper handling of the ties between the government and the market”.

One of the authors of the report, Liu He, director of the Central Leading Group on Financial and Economic Affairs and a deputy director of the National Development and Reform Commission, actually became a superstar. And just before the Plenum, President – and CCP general secretary – Xi Jinping stressed, “reform and opening up are a never-ending process”.

I want my glasnost with ice, please

So what will this glasnost with Chinese characteristics really amount to? Chinese public opinion still has not had access to the details of the dragon enigma inside the riddle – or vice-versa – although everything about these reforms directly impacts the lives of 1.3 billion people. Actually the box containing the enigma is hidden inside a pyramid – reflecting a decision process monopolized by a wise and benign party elite. “Transparency”, here, does not even qualify as a mirror image.

Everyone was expecting party pledges to increase the independence of the Chinese judiciary system and to keep fighting corruption and social injustice.

Everyone was expecting a softening of the 33-year-old one-child policy – allowing more couples to have a second child; that’s natural, considering the CCP aims for a consumer-based economy just as the Chinese population is aging.

Everyone was expecting the tackling of land reform, directly linked tothe new urbanization drive.

And for the record, this is the first time the CCP acknowledged that “both the public and private sectors are the same important components of a socialist market economy and the important bases of our nation’s economic and social development”.

In practice, this will mean the CCP breaking up state-sector monopolies in a few strategic industries. Private investment would be allowed, for instance, in banking, energy, infrastructure and telecommunications. This will also mean that many state-owned enterprises will cease to operate like arms of the government bureaucracy. In this case, expect fierce opposition from the proverbial entrenched interests – as in regional political elites fighting Beijing.

The CCP’s master plan is to expand the Chinese middle class to more than 50% of the population by 2050 (it’s currently at 12%) – equalizing more consumption with social stability. For the moment, the public sector accounts for 25% of China’s GDP. Most businesses in China are public/private enterprises already – but with 25% of all private enterprises having state-owned parent companies. Only 1.3% of Chinese workers are private entrepreneurs. Two-thirds of them previously worked in the party-state system. And 20% held a leadership position in their government or local party system.

The central role of the state should not be altered by the coming reforms. After all, 40% of entrepreneurs are members of the CCP. They made a handsome profit from housing privatization. They offer no political opposition to the CCP – and will certainly profit from the reforms. What they want most of all is a more efficient system and more social justice. They harbor no regime change ideas.

Watch these comrades rip

In the end, the absolute key problem for China’s next drive can easily be formulated Chinese-style; how to tweak the economy without any political reform. Even the Little Helmsman Deng Xiaoping – arguably the greatest statesman of the second part of the 20th century – repeatedly stressed that economic reform in China would not go very far without a political system reform.

In the short to medium term, it’s hard to see the CCP allowing the caprices of the Goddess of the Market to shake, rattle and roll the Chinese economy at will. More “market”, Western-style, will inevitably accentuate regional inequality to prohibitive levels – exactly when the CCP is trying very hard to ramp up the development of the poorer interior provinces.

The cryptic communique is of course only an abbreviated road map. It will take days, weeks and even months for its detailed implications to sink in. What’s certain is that the “decisive role” of market reform implies the CCP at the helm, monitoring every step of the process.

It’s like a ninja trying to tame a very powerful dragon non-stop. It will be an epic battle for the ages, to watch the CCP – an immense structural bureaucracy inbuilt in the Chinese government – perform this balancing act; matching its instincts for even stronger centralized control (not much glasnost allowed in the Internet, for example) with an explosion of social Darwinism caused by these “irrational” forces who couldn’t care less about employment and social stability.

Gweilos – or foreign barbarians in general – will underestimate Chinese resolve at their own peril. When the Little Helmsman launched his own economic reform – and brand of glasnost – in 1978, he turned the CCP upside down, all around, and squared the circle; breakneck economic development providing leeway to manage political problems, and some political changes allowing for even more breakneck economic development.

So what if Xi and Li come up with a Deng remix – like inventing a new concept of market with Chinese characteristics? The sky – or China back to where it was for 18 of the past 20 centuries – is the limit.

Pepe Escobar is the author of Globalistan: How the Globalized World is Dissolving into Liquid War (Nimble Books, 2007) and Red Zone Blues: a snapshot of Baghdad during the surge. His new book, just out, is Obama does Globalistan (Nimble Books, 2009). He may be reached at pepeasia@yahoo.com.

This column originally appeared on Asia Times.