By John Pilger

Source: John Pilger Website

Do actors ever reflect upon their moral responsibility for the ideological trash they help disseminate?

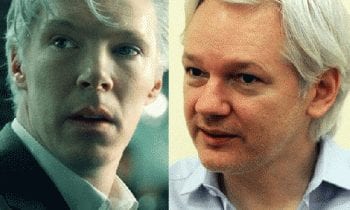

Cumberbatch and Assange: a smear job, sold as great acting.

It’s celebrity time again. The Golden Globes have been, and the Oscars are coming. This is a “vintage year,” say Hollywood’s hagiographers on cue. It isn’t. Most movies are made to a formula for the highest return, money-fuelled by marketing and something called celebrity. This is different from fame, which can come with talent. True celebrities are spared that burden.

Occasionally, this column treads the red carpet, awarding its own Oscars to those whose ubiquitous promotion demands recognition. Some have been celebrities a long time, drawing the devoted to kiss their knees (more on that later). Others are mere flashes in the pan, so to speak.

In no particular order, the nominees for the Celebrity Oscars are:

Benedict Cumberbatch. This celebrity was heading hell-bent for an Oscar, but alas, his ultra-hyped movie, The Fifth Estate, produced the lowest box office return for years, making it one of Hollywood’s biggest ever turkeys. This does not diminish Cumberbatch’s impressive efforts to promote himself as Julian Assange — assisted by film critics, massive advertising, the US government and, not least, the former PR huckster, David Cameron, who declared, “Benedict Cumberbatch — brilliant, fantastic piece of acting. The twitchiness and everything of Julian Assange is brilliantly portrayed.” Neither Cameron nor Cumberatch has ever met Assange. The “twitchiness and everything” was an invention.

Assange had written Cumberbatch a personal letter, pointing out that the “true story” on which the film claimed to be based was from two books discredited as hatchet jobs. “Most of the events depicted never happened, or the people shown were not involved in them,” WikiLeaks posted. In his letter, Assange asked Cumberbatch to note that actors had moral responsibilities, too. “Consider the consequences of your cooperation with a project that vilifies and marginalises a living political refugee …”

Cumberbatch’s response was to reveal selected parts of Assange’s letter and so elicit further hype from the “agonising decision” he faced — which, as it turned out, was never in doubt. That the movie was a turkey was a rare salute to the public.

Robert De Niro is the celebrity’s celebrity. I was in India recently at a conference with De Niro, who was asked a good question about the malign influence of Hollywood on living history. The 1978 multi-Oscar winning movie The Deerhunter was cited, especially its celebrated Russian roulette scene; De Niro was the star.

“The Russian roulette scene might not have happened,” said De Niro, “but it must have happened somewhere. It was a metaphor.” He refused to say more; the celebrity star doesn’t like giving interviews.

When The Deerhunter was released, the Daily Mail described it as “the story they never dared to tell before … the film that could purge a nation’s guilt!” A purgative indeed — that was almost entirely untrue.

Following America’s expulsion from its criminal invasion of Vietnam, The Deerhunter was Hollywood’s post-war attempt to reincarnate the triumphant Batman-jawed white warrior and present a stoic, suffering and often heroic people as sub-human Oriental idiots and barbarians. The film’s dramatic pitch was reached during recurring orgiastic scenes in which De Niro and his fellow stars, imprisoned in rat-infested bamboo cages, were forced to play Russian roulette by resistance fighters of the National Liberation Front, whom the Americans called Vietcong.

The director, Michael Cimino, insisted this scene was authentic. It was fake. Cimino himself had claimed he had served in Vietnam as a Green Beret. He hadn’t. He told Linda Christmas of the Guardian he had “this insane feeling that I was there … somehow the fine wires have got really crossed and the line between reality and fiction has become blurred.” His brilliantly acted fakery has since become a YouTube “classic”: for many people, their only reference to that “forgotten” war.

While he was in India, De Niro visited Bollywood, where his celebrity is god-like. Fawning actors sat at his feet and kissed his knees. Bollywood’s asinine depiction of modern India is not dissimilar to The Deerhunter‘s distortion of America and Asia.

Nelson Mandela was a great human being who became a celebrity. “Sainthood,” he told me drily, “is not the job I applied for.” The western media appropriated Mandela and made him into a one-dimensional cartoon celebrity tailored for bourgeois applause: a kind of political Santa Claus. That his dignity served as a facade behind which his beloved ANC oversaw the further impoverishment and division of his people was unmentionable. And in death, his celebrity-sainthood was assured.

For those outside Britain, the name Keith Vaz is not associated with celebrity. And yet this Labour Party politician has had a long and distinguished career of self-promotion, while slipping serenely away from scandals and near-scandals, a parliamentary inquiry and a suspension, having acquired the soubriquet Keith Vaseline. In 2009, he was revealed to have claimed 75,500 pounds in expenses for an apartment in Westminster despite having a family home just 12 miles from parliament.

Last year, Vaz’s parliamentary home affairs committee summoned Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger to Parliament to discuss the leaks of Edward Snowden. Vaz’s opening question to Rusbridger was: “Do you love this country?”

Once again, Vaz was an instant celebrity, though, once again, not the one he longed to be. He was compared with the infamous Senator Joe McCarthy. Still, the sheer stamina of his endeavours proves that Keith Vaseline is no flash in the pan; and is the Oscar Celebrity of the Year! Congratulations Keith, and commiserations, Benedict; you were only just behind.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Pilger grew up in Sydney, Australia. He has been a war correspondent, author and documentary film-maker. He is one of only two to win British journalism’s highest award twice, for his work all over the world. On 1 November, he was awarded Britain’s highest honor for documentary film-making by the Grierson Trustees, in memory of the documentary pioneer John Grierson. He has been International reporter of the Year and a recipient of the United Nations Association Peace Prize and Gold Medal. In 2003, he received the prestigious Sophie Prize for “thirty years of exposing deception and improving human rights.” In 2009, he was awarded Australia’s international human rights award, the Sydney Peace Prize, “for his courage as a film-maker and journalist in enabling the voices of the powerless to be heard “