Curbing the Right to Protest in Brazil

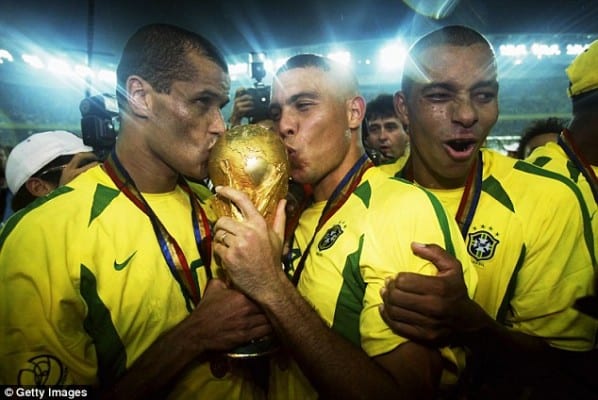

Football, for the Brazilian, is as natural in flair and living as water for fish. It shows: Brazil remains the most successful World Cup nation, winning five titles. When it exits the competition, there are sighs of remorse and tears of desperation. When it wins, natural order is affirmed. The story about the forthcoming tournament, to be hosted by Brazil, offers a very different picture.

Many matters have troubled the tournament from the beginning. There are construction issues – the Arena de São Paulo Stadium remains incomplete. “It’s not a good sign,” observed Marissa Payne of The Washington Post,[1] “when you give a news conference in front of what looks like plywood.” One end of the stadium remains distinctly unfinished[2], with ugly scaffolding very much present, and a notable absence of roofing. Brazilian clubs have been running ‘tests’ on the site, though only less than 40,000 could attend. Nerves are fraying ahead of the opener between the host country and Croatia.

This, however, seems to pall in comparison given the bad atmosphere that lingers after the million strong protests in over 100 cities during the Confederations Cup last year. Cities and streets were occupied. Violent clashes between the police and demonstrators ensued.

The protest book is filled with various grievances, but a few stand out. The World Cup, in what is virtually without precedent, is being seen as an undue extravagance. $4bn might well be invested on World Cup stadiums, but public services have been conspicuously left behind by the bookkeepers and accountants.

Infrastructure arguments have centred on efficiency for visitors, and urgency of completion, rather than such projects as housing and public transport. Indeed, it was the latter that got protesters irate in the first place when they were promised a dramatic increase in the cost of fares.

Since then, the protest platform has broadened, directed against instances of chronic corruption, issues of healthcare and education, and an emphasis on cutting funding to the World Cup itself. Like many such organizations of revolt, it has been characterised by inchoate strategies, seeking occupation and protest without firm direction. Groups and agendas vary. The support base was also affected in July last year when the more aggressive “Black Blocs” reaped the rewards of the protest by attacking banks and government buildings in the name of an anarchist, anti-capitalist credo.

Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff[3] has been rather glib about the protests, preferring to focus on the infrastructure challenges posed by the World Cup. Such is the price of democracy. “Nobody does a (subway) in two years. Well, maybe China.” The stress has been on reassurances about security, which will feature carved-up zones to enable better surveillance and population control. Protests may well be factored into the “cost” of democracy, but the police have things covered.

Research by Article 19 for a report titled Brazil’s Own Goal: Protests, Police and the World Cup[4], shows something a touch more serious than mild banter over infrastructure and policing. The right to protest is being clamped and clipped via policing and legislative channels. Evidence of this was already beginning in July last year, when the Pope’s visit saw police ban banners that could “offend the integrity of the pontiff and the nation”.[5]

The law is being used as a blunt instrument against broader protests of all kinds. The Ministry of Justice, in November, flagged the possibility of establishing “special courts” that would focus on “violators of order” with expediency during the World Cup. Laws have followed, including such laws as Draft Law 728/2011, outlining crimes and violations directly related to the World Cup. The strikingly draconian feature of the law is the terrorism offence which will have specific application to protests carrying terms of imprisonment ranging from 15 to 30 years.

Other bills make it clear what shape the harsh line on law enforcement is taking. Bill 5531/2013 targets those “threatening road transport safety”, an intended disincentive for those blocking transport. PL 6307/2103 proposes an amendment to the Criminal Code that would fine and imprison those engaged in damaging private or public property “by the influence of the crowd in an uproar.” Vague amendments to the definition of terrorism are also on the books, a boon for authoritarians keen to stifle social movements.

Thomas Hughes[6], Executive Director of Article 19, suggests that the World Cup’s arrival has shone a rather stark light on state authoritarianism, a sad state given Brazil’s recent record on civic progress. The formula of repression and violence is being used to target individual and collective freedom of expression. “Indeed, it seems that despite being led by President Dilma Roussef, who was herself tortured during the dictatorship, the state machinery still retains a military mindset, viewing even the most peaceful protest as a threat.”

On Wednesday night, 4,000 protesters[7], organised by the Homeless Workers Movement, marched in peaceful protest on the Arena, chanting for the provision of more low-income housing. Strikes are being promised during the course of the tournament. (The latest[8] is already taking place – an open-ended strike by subway workers in São Paolo.) Occupations of various office building are becoming a regular occurrence.

This promises to be a World Cup unlike any other, but that promise will say far more about state policy and protest than it will about football. The price for Brazilian democracy may well be a cost it is unable to sustain.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: bkampmark@gmail.com

Notes.

[1] http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/early-lead/wp/2014/06/02/sao-paulos-stadium-is-not-ready-at-all-for-the-world-cup/

[2] http://www1.skysports.com/football/news/11096/9334951/sao-paulo-world-cup-stadium-not-finished-sky-sports-news-geraint-hughes-reports-from-test-game

[6] http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/thomas-hughes/brazil-world-cup-protests_b_5416761.html?utm_hp_ref=tw

[8] http://time.com/2823698/sao-paulo-subway-workers-declare-open-ended-strike-days-from-world-cup/