CLASSIC REPORTAGE

Articles you should have read the first time around, but didn’t.

Report by Felicity Arbuthnot, a Freelance Journalist

At a time when the big professional press is almost entirely comprised of conformist careerists serving the lies that suit the corporate empire, it is independent journalists who carry on the task of bringing truth to the public.

We brought death and destruction on a mind-numbing scale, and brutally smashed an old civilization.

(Originally distributed 5 July 1999)

Felicity Arbuthnot is a freelance journalist, who has visited Iraq on many occasions since the end of the Gulf War. She has just returned to Britain from her eighteenth visit. In the first of a two-part interview she explained to Barbara Slaughter how she became involved. With the renewed explosion of violence in the Middle East—it actually never stops due to the innumerable tensions and forces the West has detonated and the presence of an imperialist shill, Israel—we thought this document was again worth examining.—Eds

A few months later I attended a press conference given by Magne Raundalen, a Norwegian professor in child psychology, and Eric Hoskins, a Canadian public health expert, on child trauma in Iraq. They were the first people to report what was actually going on.

Nothing was being done to help and I felt impelled to go to Iraq and see for myself. A week later I was in Baghdad and I was appalled by what I saw. It was a country which had, as James Baker had threatened, literally been reduced to a pre-industrial age; a country, which had been highly dependent on modern technology, was just being left to rot. What was unique was that this was done in the name of the people of the United Nations. It will go down in history as one of the great crimes of the twentieth century, along with the Holocaust, Pol Pot and the bombing of Dresden.

This was my 18th visit to Iraq since the Gulf War. The last four have been very close together: last October, January/February, I went back at the end of March and then again in May.

Each time I am struck by the deterioration. Each time there is another horror. In March it was the daily bombing of the infrastructure. The electricity has just died. Many people can’t afford candles and use makeshift lamps. People put a wick in a bottle with oil and quite often the bottle explodes. The injuries have soared. The burns are horrendous and there is no treatment, not even cling film as an emergency measure to cover the wounds. There are no painkillers. There is no plastic surgery.

There were two other things I noticed. Like with every embargo in history, there was a small amount of profiteering in money dealing. You have a fraction of the population at the top of the regime who have family abroad sending in dollars. There are restaurants springing up. You can get Christian Dior sunglasses, absolutely anything. Yet 98 percent of the population don’t have a way of sterilising burns.

The other thing that struck me was the breakdown in the spirit of these very brave people. They feel that it is never, ever, going to end. Yet when I became ill on this trip, they were so concerned. I suddenly collapsed in the hotel foyer in Mosul and was virtually unconscious. My interpreter and my driver kept letting themselves into my room, touching me on the head and saying: “Are you all right? Shall we get a doctor?” They were saying, “You keep coming back here and Iraq has made you

so ill.”

I was in and out of consciousness for about 18 hours. I don’t know what caused it. I just think the atmosphere is poisoned. The colleague I was with was also affected. She would be ill and I would do the interviews and then she would do the interviews the next day. We didn’t go to hospital because we felt that we would be taking medicines needed for other people, so we just battled on. It was a nightmare, but they were apologising to us because Iraq, where they had to live, had made us ill.

What we have done in Iraq, Syria, Libya, Yugoslavia and scores of other nations is nothing short of utter sadistic barbarism of the most revolting sort, paid for mostly with US taxpayer dollars, and underscored by the appalling ignorance and passivity in which Western propaganda maintains its home populations.

Another thing that struck me was the unique way they have of announcing a death in Iraq. They have these death notices, which are called naie. They take a large piece of black muslin and they write on it in white—the name, the age, the cause of death. Then they write the name in bright yellow. They put one outside the home and, if the person has died somewhere else, one there too. In March, if you were driving around for an entire day, you might see perhaps two. This time, in 13 blocks in one

area of Baghdad, I counted 18. It became a thing, to count them. In one very small square, there were three on one wall—so the whole family had died—and one on the opposite wall.

Iraq has been more or less at war for 20 years, starting with the Iran-Iraq war. It is a nation that has been starving for 10 years. The doctors say that more and more people are dying, particularly young men aged 30 to 35. These are young men who have had all their formative years under the embargo. Now they see middle age approaching and they just give up and die.

Mosul is in the “no-fly zone”. What a misnomer! The British and the Americans are bombing there every single day—with a two-week break in March and a four-day break in May. One day last week, there were 100 sorties. At night you can’t sleep for the sound of anti-aircraft guns.

I’d gone to the area near Mosul because I’d heard that they were bombing flocks of sheep. Middle Eastern friends told me that it was becoming like a target practice for the pilots. They are also bombing in Basra but I was in Basra in March. Mosul has the largest Christian population in Iraq. It has ancientChristian monasteries and wonderful buildings that go back to the time of Petra. I went in search of the flocks of sheep and found one in the middle of the plain, in the middle of nowhere, that had been bombed on April 13.

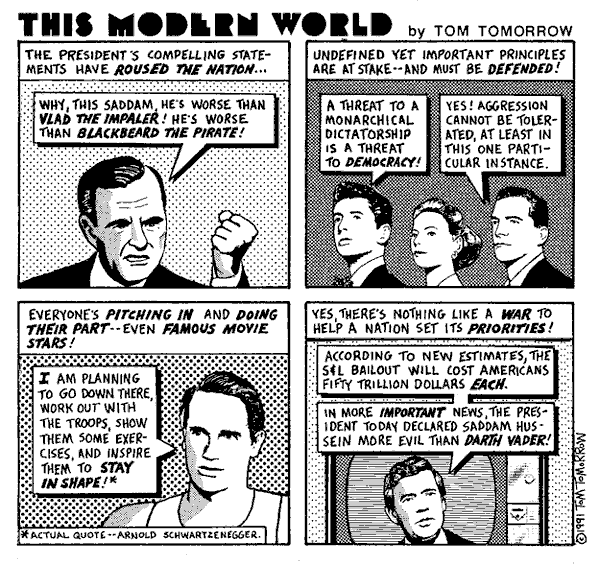

Antiwar protests against the first Gulf War. There were even more domestic and worldwide protests against the Bush 2 aggression, in 2003, but US propaganda won the day.

We went to the village where the family of the shepherds lived. A little, tiny, very poor, pastoral village of Christians and Muslims, with no oil installations and no military. The houses were built like the adobe houses in Arizona. These people had been living together in a mixed society of Muslims and Christians for centuries.

The bombing took place on a Friday, the Muslim Sabbath, and a very hot day. There were 105 sheep and goats. About 50 people had gone down to the plain with the shepherds. In the early dawn, before it got hot, they were having a kind of Sabbath celebration and sharing their food and drink. Then the villagers drifted off and the family of six were left. There was the grandfather, who was 60, the son who was 37, and the four children of whom the youngest was a boy of six.

As they left, the villagers heard a plane circling. It circled for about three hours, and they were listening because the area has been bombed so many times. Then they heard the bombing and they ran to see if they could help. They searched for the entire day, and by nightfall, they could only find enough remains to bury the family in two tombs instead of six. They could identify the torso of the old man, and that’s all they found. His head, his arms, his legs, were all blown off.

The six-year-old boy, Soultan, had just finished his second term in school. His marks had been very good and he was so proud of them. There is still this incredible adherence and passion for culture and education in Iraq. He had got a ballpoint pen (vetoed by the UN) and a piece of paper (also vetoed by the UN), and taken them down into the fields with the sheep to practice his writing and arithmetic.

The villagers couldn’t identify even one bit of him. One of his relations looked at me and grabbed my notebook. It was a very personal thing—almost like a sort of “witness”. He said, “I have to write not you. I have to write their names down in your book.” His hand was shaking and he had tears on his cheeks. When he wrote the name of the little boy he said, “What do they want from us? All he had was his pen. Is that what they want?”

This area is in the middle of a huge plain, surrounded by mountains, with a tiny village nearby. The sheep would have stood out starkly. The family had a red tractor with them and a battered white Toyota pick-up truck pulling a water barrel for the sheep. All of this would have been clearly visible.

I spoke with a Dominican priest, who was from the Lebanon. He was 60 years old and very academic and measured, but he was incandescent with fury. He told me that the Iraqi people are very moral, and that they only had their dignity and their morality left. He said, “Just before you arrived, 24 people in a Christian village, a small pastoral community living totally off the land, were killed by an American bomb. It’s just the Americans and the British.”

I heard this repeatedly. “The planes take off usually from Turkish air bases,” he continued. “We keep reading in the western media that they are bombing legitimate targets—such as radar that is locked on to them. Why don’t they say that they are bombing just for the sake of it, because that’s what we see?

“Every day mothers are losing children, children are losing mothers and fathers, brothers are losing sisters, sisters are losing brothers. This is the cost of it.”

He made a very interesting point, which the Ministry of Defence and the Americans won’t talk about. He said, “They are bombing from a distance of fifteen kilometres, but our anti-aircraft guns only have a distance of five kilometres. So how can we be a threat to them?”

I rang the Ministry of Defence and said, “I’ve just come back from Iraq and I’ve seen evidence that you are bombing sheep. What are your comments?” The spokesman replied, “We reserve the right to take robust action whenever we are threatened.” I asked “Against sheep?” Then I just gave up and put the phone down.

Another question that has to be asked is whether they are continuing to use depleted uranium bombs? I looked for evidence, but didn’t find many pieces of the tractor and none of the bomb. The relatives told me that the authorities took the fragments away. They said it was a 500lb bomb, and the crater confirmed this. But I couldn’t get confirmation of what type it was. The senior spokesman at the Iraqi Ministry of Defence said, “We are not releasing anything on the bombing until we are one hundred percent sure, because everything we say is rubbished by the western press and the United Nations.” In my experience this is true.

I asked the Ministry of Defence in Britain whether depleted uranium missiles are being used in northern Iraq, but they refused to comment. I asked whether they were using them in Yugoslavia and were we going to see a crop of birth defects and cancer like we are seeing in Iraq? Are we going to see a rerun of Gulf War syndrome now the soldiers are on the ground? He replied, “Our personnel have been given the strictest instructions, handed down by the Minister for the Armed Forces, Douglas Henderson, to all the senior officers, that none of our personnel are to approach anything that might have been hit with depleted uranium—any burned out tanks—absolutely totally not. And if it is unavoidable they are to be issued with special instructions, special protective clothing, and special breathing apparatus.”

I then said, (and this applies of course both to Iraq and Yugoslavia), “Excuse me, but what about the people living there? What about the refugees?” He would only address Yugoslavia and he said, “That’s up to UNHCR”. So I asked if UNHCR had been informed. He didn’t know and I haven’t been able to contact anyone that does know.

One of the questions I’ve asked both in the west and in Iraq is why are they targeting sheep, and I really can’t come to a conclusion. It seems so irrational, but I wonder, is it just target practice, or is it their intention is to destroy the food chain? For these pastoral people, the sheep, the barley and the wheat they produce are everything. It’s so basic and nothing is wasted. They use the meat and they sell the excess. They use the leather. They use the wool. Every single bit of it is utilised. They boil down the bones for soup, for gelatine and for preserving. This is all they have.

After the Gulf War even the date crop went wrong. Dates are just dates. They sit on top of a palm tree and just grow. You don’t spray them with anything or fertilise them. But there was no date crop for five years. The date harvest in Iraq is a big thing. They have nearly 600 different kinds of dates and they were the world’s biggest exporter. But they killed the date crop.

Since then there has been the screwworm epidemic, foot and mouth disease, which are both non-endemic to that country. There are now reports of locusts—also non-endemic. It’s difficult to know what is going on, but what is certain is that there are diseases happening right across agriculture affecting flora and fauna, in Iraq that have never been seen before.

All over the area where the bombing happened there are monasteries going back to the period just after Christ. There is a Dominican monastery where it is said that St Matthew was buried. On the other side of the valley, there’s a mosque named after Jonah, who is reputed to be buried in the same place. We went to this wonderful Christian monastery on top of a mountain and I interviewed one of the priests. He was blind. He told me that St Matthew had powers of healing and people come for healing from all over Iraq, from all denominations and all religions, to this ancient little chapel.

While we were there an ambulance drew up. There aren’t many of them, so they must have been a relatively wealthy family. Inside was a wAmman who had been in a coma for eight months. Something had gone wrong with the anaesthetic she had been given. There are all sorts of problems with the stuff that’s going in. The wAmman was a Muslim and her father was a surgeon in the same hospital where she was being cared for. They were coming for healing from a Christian saint, and just down in the valley we were bombing pastoralists with their flocks of sheep.

On May 18, Tam Dalyel MP asked Tony Blair why the bombing was continuing. Blair replied, and I quote, “We are doing it for the protection of the people of Iraq.” When I told this to the Dominican priest, he said, “They are saying this in the British parliament? In the Mother of Parliaments they are saying this?”

The current claim from Blair and Clinton is that Iraq is withholding food and medicine—that the warehouses of Baghdad are overflowing. But even a spokesman for the UN has admitted that the logistical problems are an absolute nightmare. There are no refrigerated trucks; there are no phones outside Baghdad. You have to target these inadequate amounts very carefully. You have to know what Basra, which is seven or eight hours away, actually needs, You have to know whether they have a refrigerated warehouse. Well you probably know that they haven’t, because the electricity is off practically seven days a week now. So what are you supposed to do—commit medicines to an unrefrigerated truck, probably to arrive at a warehouse that has no refrigeration, then take it back when it’s going to be totally destroyed?

A few months ago a large consignment of medical equipment finally arrived in Baghdad that had been vetoed by the US since 1990. There were scanners, X-ray equipment and other sophisticated stuff. But what nobody at the UN had taken on board was that Iraq’s technical knowledge is so out of date now, that they are not able to install it. They also lacked the necessary materials for the job. For example, they need special cement, because if there is anything wrong in the cement it can interfere with the readings. So the equipment that is desperately needed in the hospitals is just sitting in a warehouse.

Al Mansour Hospital in Baghdad, was once one of the finest teaching hospitals in the Middle East. Most of the time it has no electricity. The temperature is about 125 degrees Fahrenheit; the heat is such that you are constantly in your own personal steam bath. There are children, mainly leukemia victims, dying in these impossible conditions. And the equipment needed for their treatment can’t be installed because they haven’t got the parts for the generators. When the electricity does come on you get a big surge in power, then it dies again, and then another surge. You can’t keep having these sudden great power surges without it affecting the machines. So they can’t be used.

Yet the bombing continues and has done every single day since the “cessation of hostilities” after the four-day bombing in December 1998. We’ve destroyed the entire infrastructure. And now our representatives stand up in parliament and in the Senate and blame Iraq for not being able to distribute stuff. It’s double standards on a scale almost impossible to comprehend.

I walked round the wards in hospitals in Baghdad and in Mosul, and I looked around at those kids who could be saved but were dying, for want of chemotherapy. I was with the doctors, who were trained to heal. If they had done everything they possibly could and a child died, it would be a disaster. But they hadn’t even got the necessary tools. I asked them, “How do you feel? How do you cope? How do you even get here?” Every time I got the same reaction. They almost cried and said, “You are the first person to ask me that. Everybody leans on me. How do I cope?”

One doctor told me how he’d got a job at Al Mansour hospital. He was a senior house officer and he was really proud, in spite of his problems. He thought “I’m young and I’ll survive the embargo. I still feel I have to put something back.”

He said that when he came to work there he had a car and now it has collapsed. The hospital is about twenty minutes drive from the centre of Baghdad, but the public transport system has also collapsed. When he leaves work to go home he has to walk to the main road, which takes him about an hour. Then he has to hitch hike and wait until a car stops. And because of the collapse of the social fabric, he is not even sure that the person who picks him up isn’t going to mug him for the few dinars he has on him. Then, at maybe four or five o’clock the next morning, he has to walk back on to the main road, hitch a lift and then walk an hour back to the hospital. This is how the doctors survive.

I spoke to a senior charge nurse whom I’ve known for years. She was one of the few nurses left in the hospital and again her salary wouldn’t buy you a bus ticket back into town. But she is committed because she has been there for 27 years, and she told me how proud she was in her job and her passion for these children.

She encourages them to draw pictures, if there is anything for them to draw with. She took me round the wards and said, “This is Jasmine’s picture, this is so-and-so’s picture”. Then she looked at me and at these beautiful pictures, of birds and trees and stars—one had a lovely person in a wedding dress, you know, children’s pictures with sunshine and so on. She told me all their names and ages and said, “She died yesterday. He died last week. He died three months ago.” Then she looked at herself in what I thought was a very neat, white uniform and said, “Look, look. I would have been so ashamed to come out like this, but now I don’t care anymore.” What had been her tights she had cut down and down as they had split round the back and got more and more tattered and she was now wearing them as sort of pop socks.

Then she said to me “I’ve only water to offer you, but it’s clean.” She explained how difficult it is, because her monthly salary wouldn’t even buy three bottles of clean water. But she and her sister had found a way of filtering the water that they thought was ok. “You know I wouldn’t offer it to you if I thought it would make you ill,” she said. She explained to me in this hundred and twenty-five-degree temperature how, about three weeks before, her refrigerator had finally died. A refrigerator costs three million dinars and her monthly salary is three thousand. She

explained that in this great heat they somehow needed the water to be cold. The refrigerators in the hospital do sometimes work, at least when the electricity is on. So having found a way of filtering the water, she takes what she knows is dangerous ice from the hospital refrigerators and adds it to her drinking water—this is the crazy upside down world that is Iraq.

Second Part of the Report

Members of the 101st Airborne. Armed to the teeth, but purveyors of a McDonald’s culture.

[I] think the biggest disaster is what we are laying down in the Middle East. There’s this sort of bewilderment, particularly about Britain. They have all written off the US as a maverick crazy state.

But they say, “You know, all the ties we have with Britain. We know about colonialism, we know about the spying that went on over the years, we know about the manipulation. But deep down we have had cultural ties, trade ties, historical ties. So many families have had somebody who came to Britain for postgraduate study.” And now there’s both bewilderment and a sort of hate, that a country, with which they have had these historic ties—and history is very strong in Iraq—has just

trashed them and abandoned them.

You wonder about the number of educated people who tell you in different ways, how their children repeat at night how much they hate Britain. How are these children going to grow up? How are they going to lay this thing to rest?

There is talk about lifting the embargo. Britain and Holland have put a motion to the UN, which the US has agreed to. But basically it turns Iraq into a mandate state. The big powers will be able to keep financial control, virtually forever. If Iraq doesn’t comply with whatever conditions they impose, however unreasonable they are, the plug will be pulled again. It also puts the onus on Iraq to prove that they haven’t got weapons, rather than UNSCOM having to prove that they have. It really is a New World Order that is being imposed by Britain and the US.

The parallels are so stark between Yugoslavia and Iraq, whether it’s the weapons used, whether it’s Rambouillet, which again meant the complete takeover of the country, making Yugoslavia into a mandate state. The Vienna Convention states that no treaty is valid if people are threatened and coerced into it. At Rambouillet, Britain and the US said, “If you don’t sign we are going to bomb you!” so it was an invalid treaty. They have imposed totally impossible conditions on both countries. When the Gulf War started the British parliament was in recess and so was the equivalent in the US. George Bush announced the war when he was on a fishing trip. When they decided to bomb Iraq last December, there was absolutely no discussion in parliament.

They are now operating an entirely illegal war against Iraq. George Robertson and others have said, “We were not at war with Iraq last December and we are not at war with Iraq now”. And Robertson and Blair say the same about Yugoslavia; “We are not at war.”

In both countries the entire infrastructure has been destroyed. Yugoslavia relies on the bridges over the Danube and all the tributaries, for international trade, commerce and travel. They have bombed all the bridges. In Iraq also, just like Yugoslavia, they have cut the country in two, by bombing all the bridges. All this is prohibited under the Geneva Convention. But they bombed five electricity stations, whilst preaching about human rights.

At a press conference on May 3, Jamie Shea made this extraordinary statement:

“The fact that the lights have gone out over seventy per cent of Yugoslavia shows that NATO has its finger on the light switch and we can turn off the power whenever we need to and whenever we want to.”

The lights have gone out all over Iraq and the lights have gone out all over Yugoslavia and with it the jobs, the normality. They bombed the telecommunications. Again it’s illegal, under the Geneva Convention. They used Iraq as a blueprint and went further in Yugoslavia. If you remember, Wesley Clark said that if the media didn’t run six hours a day of western propaganda, they would bomb the broadcasting centre and they did. The western journalists were warned not to file their reports from the television centre that night. But nobody warned the Yugoslavs.

When I was in Baghdad this time I went to what is called the Reconstruction Museum, which is in a huge, very beautiful Ottoman building beside the Tigris. They have minutely reconstructed every public building, from Mosul in the north to Basra in the south, that was damaged in the Gulf War. Then they show how they have been reconstructed. I was stunned to see that in every city the television station was bombed.

In Yugoslavia they bombed every radio and television centre. We heard about a couple of them, but in fact there were 27.

They also targeted education. In every single town in Iraq, the

educational establishments were targeted. On the same day the stores that provided educational materials were also targeted. This can only be described as a kind of cultural or historical cleansing

During the Gulf War I remember a report from a Spanish journalist going round with a very old man who was an expert on the historic sites of Iraq which appeared to have been deliberately targeted. The old man was saying, “Even during the Iran-Iraq War, with all its carnage, we had this common heritage. We respected each other’s history. There were real efforts made to avoid these sites.”

In Yugoslavia again the NATO spokesmen were actually boasting that they would teach them a lesson about history if that’s what they wanted. In Iraq this meant destroying the ancient monasteries, the ancient sites, the world heritage sites listed by UNESCO. It’s an attempt to destroy the country’s psyche, its historic soul.

There are allegations that new weapons are being used, which they simply don’t know the end result of yet. Maybe they will run on down the generations.

Another parallel is the unprecedented environmental degradation in both Iraq and Yugoslavia. We have seen the terrible toll in Iraq of the use of depleted uranium weapons—the spiralling birth deformities, the up-to ten-fold cancer increases amongst children, the toxicity which has been released and all the things that we don’t know about yet.

On the way back from Mosul we visited hospitals and found the same sort of deformities that you see in Basra. One wAmman was there with an incredibly deformed child and she had two others at home equally deformed. They had been born since the Gulf War. The doctor said that in her whole family, even the extended family, there had never ever been a deformity. What we were seeing was acute lymphoblastic leukemia, which very often results in horrendous growths behind the eyes. You see these children, who had previously been beautiful kids, who look as if

their eyes are literally going to pop out of their heads because of the pressure behind them. The doctors can’t treat them and these kids just die in agony.

Given the intensity of the bombing of Yugoslavia, we are going to see birth deformities there within a year, amongst the people and amongst the animals, and very quickly the cancer rates will rises. All these things are parallels and future generations if they survive, are going to have to live with them and with the consequences.

On the way back from Mosul, I realised that if we made a small diversion there was Hatra, which was built at the same time as Petra in Jordan—the “rose red city half as old as time”—and Baalbec in the Lebanon. It was one of the great historic sites in an area that has been consistently inhabited for the past six thousand years.

I said to the driver, “We’ve got to go to Hatra, we absolutely have to.” So we went off the road and we arrived there at five in the morning, with this azure blue sky. And there were these great columns like the Parthenon in Athens. It’s almost untouched and it is so incredible with this golden stone. We walked round in the early morning and everything was absolutely still. It was like travelling back in history. It was beyond anything you can imagine.

If the Nuremberg Tribunal precedent did not exist, it would have to be created to accommodate the crimes of the Anglo-American alliance.

An archaeologist came running out. He had been looking after this remote site for 10 years, all on his own and he was just steeped in it. And he was so proud to have people there and to show us round. At the very end he asked if we could take a photograph so that he could believe that people had actually come to see it again. Then this man, who had come out at five in the morning, with his immaculate white shirt and his pressed trousers, said, “But please don’t take a photograph of my shoes.” His shoes were so battered, because shoes cost about two years salary. This proud and educated man, who spoke five languages and is a world acknowledged authority in archaeology, said, “Don’t take a photograph of my shoes.”

As we walked round he told us that there had been a bombing nearby, but Hatra hadn’t been affected except for the vibrations. We saw this beautiful statue, about three feet high. It was like something in the Uffizi Museum in Florence, but from the original time when Hatra was built, and it had lost its head in the bombing. I just stood there in the wonderful early morning light and I thought of Flecker’s poem about the British Museum, which of course has robbed countries all over the world.

Flecker wrote:

There is a hall in Bloomsbury

That no more dare I tread,

For all the stone men shout at me

And swear they are not dead.

And once I touched a broken girl

And knew that marble bled.

In that dawn light in Hatra, a place that screams at you, “This is the cradle of civilisation”, I thought, “That’s what this statue says, that the Americans have blown the head off.”

I don’t know where it all unravels, where we go from here. The Iraqis are not going to accept this new mandate that the UN is proposing. So we have reached an impasse, where 7,000 children a month are going to continue to die until the country is bereft of its youth, bereft of its future, bereft of its hope, of its education.

The bus journey out of Iraq to Amman takes 26 hours. People who have got the money to go there for proper medical treatment sometimes die on that bus. Iraqis have to pay a huge exit fee because there is such a haemorrhage of talent from the country. Everybody who gets themselves on the bus has a story. We talked to two Shia women in their black garb—very elegant, very beautiful. They had this two-year-old boy with them, in a baseball cap and little shorts and a tee shirt. It looked very odd to see the two traditions meeting. They were actually mother and daughter and they were travelling to Jordan to look for work because the little boy’s mother had died of burns. She had been lighting one of these makeshift lamps and it had exploded. She burned to death in front of the little boy.

The other person we spoke to was a sheikh, with large horn-rimmed glasses, dressed in long white robes. He spoke better English than you or me. He told us that half his family lives in Kuwait and the other half in Iraq and there are no phone links between the two countries. He said he was fortunate because he has a little money, so every six weeks he makes the 26 hour journey on the bus, to telephone his family in Kuwait and then gets back on the bus for another 26 hours.

These are just two examples of the human cost. What has happened to the UN Declaration of Human Rights that we were trumpeting last year? What has happened to the Declaration on the Rights of the Child? And what has happened to our common humanity? It seems to me that if anybody is charged with war crimes at the International Criminal Court at the Hague, it should be the leaders of NATO, the leaders of Britain and the United States.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Felicity Arbuthnot is a print and broadcast journalist specialising in the environment and the Middle East and is cited as an expert on Iraq. Author, with Nikki van der Gaag, of “Baghdad” in the Great City series for World Almanac books, she has contributed to many anthologies on Iraq and been Senior Researcher for Award winning documentaries. She is Human RIghts correspondent for The Centre for Research on Globalisation.