Poor, Poor Pitiful Me

[P]ity Hillary. Evicted from her home, jobless, and, as she evocatively put it to Diane Sawyer, “dead broke.” Such were the perilous straits of the Clinton family in the early winter months of 2001, as they packed their belongings at the White House, and scurried away like refugees from Washington toward a harsh and uncertain future.

“We came out of the White House not only dead broke, but in debt,” Hillary recalled. “We had no money when we got there, and we struggled to, you know, piece together the resources for mortgages, for houses, for Chelsea’s education. You know, it was not easy.”

Hillary was on the cusp of middle age and, at this point, for all practical purposes a single mother. She hadn’t had a paying job in years and the prospects of resurrecting her law career were dim. She was emotionally drained, physically debilitated and hounded wherever she went by the dark forces of the right. All in all, her prospects on that cold January morning were grave.

With no life-ring to cling to, Hillary was forced to work furiously to save her family from a Dickensian existence of privation and destitution. Though she spared Sawyer the harrowing details, we can recreate some of her most grueling tasks. This meant giving several speeches a week to demanding audiences for $200,000 a pop, burning the midnight oil to complete her book so that she wouldn’t have to return her $8 million advance, booking Bill’s speeches at $500,000 an

appearance and scrutinizing Bill’s $10 million book contract for any troublesome pitfalls. There were also those tedious documents to sign for Bill’s $200,000 presidential pension and her own $20,000 annual pension for her term as First Lady.

appearance and scrutinizing Bill’s $10 million book contract for any troublesome pitfalls. There were also those tedious documents to sign for Bill’s $200,000 presidential pension and her own $20,000 annual pension for her term as First Lady.

There was also that rather irksome request from the Banker’s Trust that Hillary authorize them to accept for deposit $1.35 million from a certain Terry McAuliffe to secure the Clinton’s loan for the purchase a five-bedroom house in Chappaqua, New York. She was also tasked with itemizing the $190,000 worth of gifts for the family’s new home that flooded into the White House during the last cruel weeks of the Clinton presidency and arranging moving vans for the $28,000 of White House furnishings the family took with them to their humble new digs in New York.

But Hillary put her nose to the grindstone. She didn’t complain. She didn’t apply for unemployment compensation or food stamps. She simply devoted herself feverishly to the tasks at hand and over the course the next few months the Clinton’s fraught condition began to improve rather dramatically.

By the end of 2001, the Clintons owned two homes: the $5.95 million Dutch Colonial in Chappaqua and the $2.85 Georgian mansion in DC’s bucolic Observatory Circle neighborhood. Her deft management of the family finances, a feat worthy of Cardinal Mazarin himself, allowed the displaced couple’s bank accounts to swell to more than $20 million. A carefully nourished blind trust also fattened to more than $5 million. In twelve short months, their net worth rose from “dead broke” to a fortune of more than $35 million. Thus was the Clinton family was saved from a life of poverty.

The Clintons’ rapid reversal of fortune was almost as stunning as Hillary’s miraculous adventures in the commodity market in the 1980s, when with a little guidance from broker (and professional poker player) R.L. “Red” Bone, she shrewdly turned a $1000 investment in cattle futures into a $100,000 payday.

One might call the Clintons’ economic odyssey an American morality tale. It is the story of how a besieged family, staggered by the loss of a home, suddenly without an income and pursued by creditors, can pull themselves up from the gutter through persistence, hard work and a goal-oriented plan for success.

This exemplary narrative of self-salvation must have confirmed in HRC’s mind the righteousness of her decision in 1996 to run interference for Bill’s drive to demolish the federal welfare system. In that fateful season, Hillary assiduously lobbied liberal groups, including her old outfit the Children’s Defense Fund, to embrace the transformative power of austerity for poor women and children.

Over the next four years, more than six million poor families were pitched off the welfare rolls, left with only their own ingenuity to keep them from being chewed apart by the merciless riptides of the neoliberal economy. Politicians cheered the shrinking of the welfare state. Hillary boasted of moving millions from a life of dependency toward an enchanting new era of personal responsibility and economic opportunity.

But what really happened to those marginalized families, did the village rush in to help rear those millions of destitute kids, suddenly deprived of even a few meager dollars a month for food and shelter? Hardly. In 1995, more than 70 percent of poor families with children received some kind of cash assistance. By 2010, less than 30 percent got any kind of cash aid and the amount of the benefit had declined by more than 50 percent from pre-reform levels. During the depths of the current recession, when the poverty level nearly doubled, the welfare rolls scarcely budged at all and even dropped in some states.

More savagely, most of those “liberated” from the welfare system didn’t ascend into the middle class, but fell sharply into the chasm of extreme poverty, trying desperately to live on an income of less than $2 a day.

Still $2 a day is better off than being “dead broke.” Indeed, those forlorn mothers can always put down their last few bucks on the futures market. After all, as HRC reminds us, children are the future.

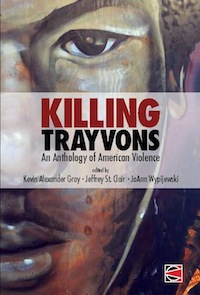

Jeffrey St. Clair is editor of CounterPunch. His new book Killing Trayvons: an Anthology of American Violence (with JoAnn Wypijewski and Kevin Alexander Gray) will be published in June by CounterPunch Books. He can be reached at: sitka@comcast.net.