ARTICLES OF LASTING INTEREST | ARCHIVES | RUSSIA DESK

![]()

ECONOMIC CRISIS

The situation as seen by one of Russia’s most insightful political analysts

(Originally published Monday 4 April 2011)

Deep-rooted changes have happened in Russia as a result of its embrace of neoliberalism. It seems to have affected the entire landscape of Russia, not only socio-political and economic but also all other facets of society. A very dramatic example is the forest fires that raged through much of the summer of 2010. It was reported that in August alone there were 554 fires in an area of more than 190,000 hectares (469,000 acres). Hopefully, in India it can serve as a dramatic lesson and warn people of the dangers of the state completely withdrawing itself and surrendering to market forces.

The forest fires of this summer were really in a way the moral and cultural turning point. They revealed the state of permanent disaster into which Russian society has moved in the past 17 to 20 years. It will be absolutely wrong to present these fires purely as a natural disaster, which, of course, the government tried to do. Interestingly, no one in Russia was prepared to accept it. Ultimately and ironically, even the government had to accept that it was a man-made disaster. The fires did not result from global warming or climatic change and higher temperatures. Forest fires are common and happen everywhere, but the fact that it spread on such a large scale and became uncontrollable was because of privatisation. Neoliberal legislation in the form of a new liberal forest code led to the privatisation of Russia’s forest resources. This also meant that the state or its agencies could not intervene in these forests.

As a result of the privatisation of forests, structures that existed to deal with such situations had been dismantled and the management structure, technology and equipment that existed earlier were no longer available. Worse, in the current privatised context the fire brigades and fire-fighting agencies under state control could not enter the forests unless invited by the private owners. So you had a situation where once the forest fires started they were not, and could not be, brought under control, a fact that was not at all highlighted in the international media coverage of the forest fires.

Whole villages were wiped out in the range of 2 or 3 km of the fires. People were simply running away and some of them crossed to the Belarus side of the border and discovered that on the Belarus side, where the climate was the same, the temperatures were the same, there were no forest fires and even if there were some incidents they were extinguished immediately, maybe even in minutes. This is because, people discovered, they had retained the old Soviet system of state control over forests, and this meant that the forests were being monitored regularly and managed by personnel from the state forest services, and a close watch was being kept on preventing any such disasters.

There was a famous satellite picture of the forest fires that showed on the western side fires everywhere and on the eastern side no fires; one could clearly see the frontier as the forest fires raged on the Russian side. That became very important in terms of revealing to the Russian public the total bankruptcy of the Russian elite-controlled state and the level of disorganisation of government at the local level. Even the Central government was shocked by the scale of corruption and insubordination at the local level. Putin then actually went to the villages that were destroyed and seeing the rampant corruption ordered that the reconstruction being done be recorded by video cameras and webcams to reduce the corruption and to ensure that the money given to the local authorities is actually used for the reconstruction of these villages. You know what happened next, most of the webcams and video cameras were stolen. So that was the end of the story. Both the forest fires and the attempts to control the situation became a huge scandal.

In your book “The Empire of the Periphery: Russia and the World System” you say that even before the collapse of the Soviet regime, under perestroika itself Russia was being reduced to a mere raw materials exporter and its economy was reduced to dependence on raw materials. This was because in the years leading up to the years of perestroika the Soviet Union had already been reduced to a very indebted country.

“The old Soviet system of state control over forests [performed better than the one in private hands]

READ MORE CLICK ON THE BAR BELOW

[learn_more] and…this meant that the forests were being monitored regularly and managed by personnel from the state forest services, and a close watch was being kept on preventing huge disasters like great forest fires. The forest fires of this summer were really in a way the moral and cultural turning point. They revealed the state of permanent disaster into which Russian society has moved in the past 17 to 20 years. It will be absolutely wrong to present these fires purely as a natural disaster, which, of course, the government tried to do. Interestingly, no one in Russia was prepared to accept it. [/learn_more]

[learn_more] and…this meant that the forests were being monitored regularly and managed by personnel from the state forest services, and a close watch was being kept on preventing huge disasters like great forest fires. The forest fires of this summer were really in a way the moral and cultural turning point. They revealed the state of permanent disaster into which Russian society has moved in the past 17 to 20 years. It will be absolutely wrong to present these fires purely as a natural disaster, which, of course, the government tried to do. Interestingly, no one in Russia was prepared to accept it. [/learn_more]

REGULAR ARTICLE RESUMES HERE

Actually, the huge debt was the turning point. Many people see perestroika as the turning point, but I am trying to show in my analysis that the turning point happened much earlier, in the second half of the 1960s and the early 1970s. In the 1960s it became very clear to society and to the leadership that the Soviet society was in a deep need of transformation, and my point of view is that, ironically, the Soviet system was facing challenges not because of its failures but because of its successes. The system was heading towards what seemed a collapse not only because of the lack of democracy and so on but actually because of its successes and achievements. This is the kind of dialectics of history.

The Soviet system was designed to develop the country rapidly into an industrialised society and economy. So, actually within less than two generations the Soviet society had been transformed from a rural, agricultural, backward and, in many ways, weak society into a tremendous industrial power. By the way, this achievement of becoming an important industrial power was also realised by investments in science and technology and important breakthroughs in this field, including, very interestingly, the successes of Soviet geological science, which was able to show how rich the country was in terms of minerals and raw materials. The latter happened precisely because under the conditions of the Cold War the former Soviet Union had to prioritise access to and supply of raw materials and mineral resources. In the period beginning with the 1930s and into the war period and especially in the 1950s, there was an enormous effort to turn the country into a rich country in terms of resources.

This, however, could not continue running on the lines similar to those of the 1920s. So, in the late 1960s the bureaucracy made a conservative choice to consolidate the system, which needed to be backed by some kind of material feasibility. It was the crisis in 1973 that changed the situation, with an increase in the price of oil and the growing demand for raw materials in the West and around the world. With the sudden income and short-term prosperity due to the oil resources available within the Soviet Union, the Soviet leadership believed it could buy everything the country could not produce. For example, in matters relating to Soviet science and technology outside of defence and the military, the policy of the government was: if there was a problem with technology, simply buy it from abroad for oil; if society is short of consumer goods, get them from abroad, and so on.

The problem at that point was that the Soviet Union was reintegrating into the global capitalist economy not as a successful industrial country with high scientific development, which it was, but as a producer of raw materials, which meant a semi-colonial type of reintegration.

In my book, I point to the fact that much of Russia’s history is imperial elite self-colonisation. The price that Soviet society paid during the elite self-colonisation period was very high. They were unconscious of the problem and did it spontaneously. But the problem was this logic of self-colonisation developed its own structures and outlook that reshaped the elites and their behaviour. So, by the end of the 1980s and in the beginning of the 1990s, it was a conscious effort of the elites who wanted to become a part of the global system and a part of the global bourgeoise, sacrificing much of the achievements of the Soviet period, in order to obtain a good position in the club of the global elites. As one Russian politician said, our dream is to become members of the board of directors of the company called ‘The World’.

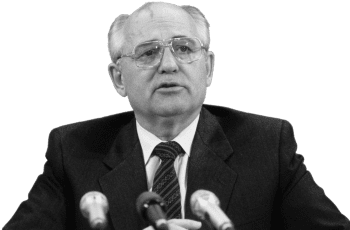

Did Gorbachev represent that elite?

Mikhail Gorbachev: Proceeding almost unconsciously, but representing a strong current in the elites, he dismantled the Soviet Union, only to deliver it into the hands of capitalist vultures and their figureheads, like Yeltsin. (click to expand)

Gorbachev was not conscious of what he was doing, but his entourage was truly conscious. Yeltsin was very conscious. That is why they had to replace Gorbachev. He was moving in that direction spontaneously, but not consciously. But what they had to sacrifice was not only some of the social achievements of the Soviet period, many of the achievements of industrialisation and the status of superpower, but the Soviet Union itself. So the country disintegrated.

The Collapse and after

You deal with that period of the collapse in your book. I am referring to the period of the collapse in 1991, especially the sudden and dramatic change in wage levels in Russian society compared with what they were in Soviet society. You provide figures in your book on the kind of differences in wage levels. The other important reference you make is on what was happening in the scientific world. As you mentioned earlier, in the Soviet period the scientific intelligentsia played a key role in knowledge power, in innovation power, within the constraints of the Cold War. In that very short period of less than a decade, two types of scientific intelligence emerged, one hooked to the West and privileged and the other completely cut off and impoverished. I see many parallels to India. I want you to elaborate about the collapse in 1991.

After 1991, the opening up of the economy was accompanied with the crass ideological belief that products that are not needed by the world market don’t deserve to exist at all. In a certain sense, if you extend that a bit further, what the Russian elite did was to say that people who are not in demand in the world market do not deserve to live at all. I am not exaggerating. The ruling elite, whether it be in government, the corporate executives, the oligarchs, thought and functioned exactly in this manner.

These goods were nevertheless needed by those people who used them and by the people who produced them, as they created employment and subsequently development. In that sense, when our products are not marketed at the global level, it does not mean that the products are not necessary. However, the complete opening up of the economy and the elimination of all sorts of protection for industry led to the destruction of much of the industrial capacity.

Further, much was achieved through the combination of open markets and a high exchange rate for the rouble. At first there was hyperinflation that led to the almost complete destruction of popular savings, while the elite faced no problem as their privatisation was not based on sales but on giving the assets away to their friends. The actual savings of the people were destroyed, but [this] did not damage the process. Then, the hyperinflation led to the elimination of competition from the bottom, in the process of privatisation and the opening up of the economy. People, apart from the elite, could not use the advantages of the open market policy though they were minimal; even within that approach people were at a disadvantage. After they wiped out the popular savings, they started increasing prices and stabilising the rouble, which meant that those who had accumulated resources and had started accumulating money/capital were now in a favourable position.

It was a very conscious policy of depressing a large section of society while creating good conditions for the newly emerging bourgeois-upper class to create a society that is more socially differentiated compared to the Soviet society, which was very egalitarian. However, the side effect of this policy with an open market alongside a currency that was overpriced was that industry was becoming less competitive, which meant that the only thing you could sell was natural resources such as minerals and oil, which had a worldwide demand. Other resources were facing losses. For example, during that time, coal mines were running at a loss and the World Bank gave Russia a $500-million credit to close the mines in Siberia. In 1998, just before the devaluation of the rouble, Russia was asked by the World Bank to buy coal from Australia, as it was cheaper, though Russia had large coal deposits. They gave the $500-million credit to shut down the Russian mining industry! But, fortunately for Russians, the World Bank money was stolen by some people in the Ministry or government and nothing reached Siberia where it had to be spent.

A few months later, the government asked for more money from the World Bank, but this time the Bank refused as it insisted on being told what happened to the initial credit provided. At that time the rouble crashed; it used to be six roubles to a U.S. dollar, but after the crash it was 12 roubles and a few months after that 24-30 roubles to the dollar. By the way, Moscow Times reported, with a glint of pride, that the Russian rouble was now the fastest falling currency in the world. Right after the crash, one suddenly discovered that Russian coal was competitive; the very same mines, workers and managers all of a sudden, given the devaluation of the rouble, became very productive and profitable.

When you say that particular people and products are not capable of competing on the world market, among other things, it is not about the products, people’s skills or the way they work, it is completely independent of its people. It is, on the contrary, how financial institutions operate, like how they fiddle with the exchange rate of the currency. So, the Russian economy suffered both from the open markets and from the policy of financial stabilisation, which inflicted even more damage. We ended up losing 40 per cent of the industrial capacity we had in the 1990s. A disastrous figure, it was one of the worst-known historical disasters in peacetime; to make matters worse, the lost industrial capacity was never recovered. Even though the first decade of the 21st century was considered a successful decade with a lot of economic growth, it did not lead to Russia recovering much of its industrial capacity.

Social compromise

The way in which Russian capitalism emerged, based on the Soviet Union’s managerial system, and the subsequent events of the 1990s and the emergence of an oligarchic capitalism are in a sense similar to the way in which oligarchic capitalism is developing in our societies also. This is true for much of Asia, including India, and we can see how Indian and Asian democracies have also become oligarchic democracies. In the context of the rise of oligarchic capitalism in Russia post the Soviet Union, can you briefly cover the transition from Boris Yeltsin and Victor Chernomyrdin to Yevgeny Primakov?

There are two stages, the first was when Yegor Gaidar and the most extreme free marketers ran the country for less than two years and were forced to leave. Their political positions started weakening even before the conflict of October 1993. Chernomyrdin emerged earlier, but Chernomyrdin initially didn’t have enough power to change the logic of the transition. So by 1994, a new compromise was made between the industrialists/managers and the new financial oligarchy that emerged out of the party structures and the Youth Communist League [Komsomol] structures, and they managed privatisation together. While the party people ran the show in general, specific financial structures were often devolved by junior partners from the former Komsomol. Both groups of people were extreme free marketers and neoliberals, while the industrialists were a bit more moderate as they did not want the destruction of the industries.

In the period between 1993 and 1998, when privatisation was achieved, the property was divided between the new oligarchs and the party managers, but the permanent looting of the country’s resources led to an economic crisis of tremendous scale and left the country in a bad shape. And in 1998 the rouble crashed, and that led to a sudden forced shift to some kind of Keynesian policy that Primakov and the others tried to represent. [It was] a social compromise involving the most realistic, progressive elements of the Russian managerial class to try and save as much of industry as possible, and they succeeded in doing it.

So, the Primakov government was the most successful government in post-Soviet Russian history as it managed to reverse the trend and the economy started growing. However, it was like any other reformist, social democratic government that did not have a strong power base in the trade unions, in the labour movement. Immediately after they technically fixed the capitalist system or did their jobs, the capitalist system did not need them anymore. So Primakov was fired and after an interim period, an interregnum, Putin was made the new top manager.

Putin’s Bureaucracy

Putin tried to give neoliberalism a bureaucratic face, not a human face but a bureaucratic face, trying to use with maximum efficiency the traditions and methods of Russian bureaucracy to manage the transformed economy, which became neoliberal. It can be perhaps called neoliberalism with a bureaucratic face.

Talking of Putin, why the bureaucracy was important must be understood. A powerful bureaucracy was required as the oligarchs were becoming dangerous to themselves. Just as children when they are playing with matches or scissors or knives, and when you take it from them they get upset, the oligarchs behaved in a similar fashion when Putin was actually protecting them from their own stupidity and irresponsibility.

The Russian elite largely understood this and backed Putin, while some individuals disapproved. Those who continually misbehaved were thrown out. Specifically [Boris] Berezovsky, [Vladimir] Gusinsky and [Mikhail] Khodorkovsky, continued to strongly disapprove. They managed to force Bereszovsky to leave the government and go into exile. Gusinsky was arrested, released within days, and forced to go to Israel as he was running a propaganda campaign against Putin. As for Khodorkovsky, who was very aggressive and desired to become the Prime Minister and was trying to organise a coup d’état, he was arrested. However, it was not for his political intrigues or for an attempted coup d’état but for not paying taxes, like Al Capone.

When you talk of the technocratic elite in the policy sense… and your reference to the scientific intelligentsia that it believes that if you privatised, liberalised and took away the so-called yokes of government we will be moving fast… On the other hand, the technocratic elite thinks that with technocratic reforms (bringing in greater digitisation of government services and so on) things would happen. In this context, in your book you say that “the scientific intelligentsia saw themselves in the 1990s as a potential counter-elite”. You also quote Alla Glinchinova, senior researcher at the Institute of Philosophy of the Russian Academy of Sciences, which is so apt in our Indian context. She is quoted as saying, “Some perceived the liberal slogan of privatisation in the name of freedom, progress and the overcoming of stagnation as a path to weakening and doing away with informational and administrative inequality and privileges. Both elites put their stake on economic and technological change, expecting positive results for themselves.” Can you tell us about the scientific intelligentsia in the Russian context?

There was some sociological research done in the remaining scientific development centres of Russia, like Dubna and Chernogolovka. The research shows the deep concerns of the researchers themselves and that the scientific and technical intelligentsia was deeply divided into two segments. The people who are involved in a kind of marketisation drive and who think that marketisation will let them have a chance to get more money for their creativity and intelligence, and the others who are deeply opposed to that kind of approach.

Putin tried to give neoliberalism a bureaucratic face, not a human face but a bureaucratic face…

There are some people who research on certain things that are marketable, but who consider it wrong to do scientific research only for the markets. But now, with the launch of a new scientific project by the government [called] ‘Skolkovo’, a letter was sent to about 700 Russian scientists abroad urging them to come back to Russia alongside offers of a lot of money if they came back. Initially many scientists were interested, but not a single scientist has agreed. A Russian Nobel Prize winner, Dr. Game Novoselov, responded for all those who refused by saying, “All you’re saying is about money and we are not interested in the money, we are interested in science. If you offered us real scientific opportunities to achieve something for the country or for humanity, we could be interested/attracted.”

This difference of vision shared by the people shows that the government does not care about science or research; they just want a few famous scientists back in Russia, a form of public relations exercise. They think that you can buy anybody by just offering money. This is a turning point for much of this community who are saying, “If we are scientists, it is about science, not money.” The Skolkovo project is clearly failing, and its failure reveals an important point about what is happening to the intelligentsia with the shift towards research of some substance, away from the market.

China and the US

Turning to the world economy, I want to draw your attention to China. What is China’s role in propping up the U.S. economy, as it seems to be playing a major role?

Jayati Ghosh made a very important point recently, that China and to a certain extent India are becoming hostages of their own export-oriented economies given the lack of new markets. Their market space is actually shrinking. They are reaching a situation when to continue exporting to the West they have to start subsidising the West directly or indirectly. China can look technically as being in good shape. However, the problem is that it is actually not, and to continue moving in its current economic path China has to do a lot to save the American economy, unless there is a structural change. All the current measures to save American consumption will be short-term and will not solve the problem in the long run.

Ferguson, a conservative English historian, coined the term ‘Chamerica’ and said that it was a marriage of convenience. It is like a marriage between a hardworking man (China) and a lazy but prestigious woman (America) who spends the hardworking man’s money. Ferguson thinks that this marriage will last. I, however, have my doubts.

How much global economic clout do you think China has, and how much of this clout will it use to ask for changes in the global economy and in the global system?

The problem is that China does not seem to want major changes in the global system. China is looking to get a higher status within the current global system and not [seeking] the transformation of the global system. China, as far as I understand, is not interested in the role of a hegemon, not because it is not ambitious but because the Chinese look at the world in a different way. They consider it unnecessary to accept all the problems, pains and difficulties connected to the role of hegemony. They are satisfied with the role of regional dominant power and being at the same time an increasingly important global economic power. Why should China try to imitate American takeovers, it is not of interest to its national elite to become a global hegemon.

China is not trying to shape or change the global system, but is just improving its status, position and role within the system. That is exactly the contradiction. Having a higher role within a system that is going down is a very dangerous strategy because it means more trouble with a higher status in the system. This is slowly happening, as China has to spend more money on certain issues it is not interested in, as it cannot avoid them.

In your book, you make the distinction between orthodox Marxism’s analysis of what is happening to the global capitalist economy and the world systems approach, while indicating that both are important. Can you elaborate on where you see the difference between the two?

This has been developed further in my next book From Empires to Imperialism. Capitalism can be defined in two ways, either it is a mode of production or it is a system. For example, if it is a mode of production then the key aspect of it is the possibility of exploiting wage labour. If it is a system where the key element is accumulation (and, by the way, Karl Marx gives enough material for both definitions), you can accumulate through exploiting non-wage labour, slave/serf labour.

It was a very important correction that was made by Michael Pokrovsky, a great Russian historian, that there are two types of capital as well: production/industrial capital and trade capital. Trade capital has a model of accumulation that does not necessarily need much of wage labour, while industrial capital can only exploit wage labour, otherwise it is not capital. In that sense, the real division is within capitalism, because there are two types of capital.

Today they are interconnected; we do not have corporations that are purely trade corporations and purely production corporations, there are both. But still, even within these corporations, one or the other function is dominant. In that sense, neoliberalism is exactly the domination of the trade function of capital. And my point of view is that this contradiction just reflects the reality. It is not the contradiction within Marxist analysis; it is the contradiction within the reality of capitalism that Marxist analysis reflects. The only point is that we have to make it conscious. So we have to say there is a contradiction within these two aspects.

Where would you see the role of global finance capital in this?

The aspect that was absent in Pokrovsky’s analysis, which I tried to fix and recently came to the conclusion which I am still working on, is that finance capital makes alliances with one or another type of capital, thus making this particular kind of capital dominant. So, at one point, when trade capital is dominant and doing well then financial capital goes into trade capital, disinvesting the production side, very often.

But then, once this model goes into crisis, the financial capital that is the most flexible element moves back into alliance with production/industrial capital, and thus fluctuates. In that sense, financial capital can become hegemonic; it controls and shifts the alliances.

My understanding of the current crisis is that at some point the alliance between the trade function of capital and financial capital will be somehow weakened. And financial capital will move back to supporting more productive forms of capital, which will also mean a return to some kind of neo-Keynesian approach. However, the point is whether it will work out. When you move from one form of capitalism to another, opportunities open up for an attempt to go beyond capitalism; it is not just about transforming the world but to propose and successfully practise some non-capitalist or post-capitalist solutions.

They appear repeatedly during specific moments of crisis when the balance of forces within capitalism fades, such as the Russian Revolution, the situation after the Second World War, and later specifically in Latin America when the revolution happened in Venezuela. It was possible because the crisis started in Latin America before it started elsewhere. Latin America, however, was left alone because the United States was busy dealing with the geopolitics of the Middle East [West Asia]. So, these are specific moments where the balance of forces shifts and alternatives are needed anyhow. The model currently running is unsustainable and needs change. There is always an opportunity that during this change you can go beyond capitalism.

What is the special emphasis that you place on [Nikolai] Kondratiev’s analysis, what is commonly referred to as Kondratiev waves or cycles in looking at the periodic crisis of world capitalism, with reference to the current context?

The idea of Kondratiev that I find the most exciting is the idea of reconstruction. That at some point capitalism goes through a process of reconstruction, so the model changes. He does not specify why and how it changes, but at some point you are going to come to some kind of a break where you have to build a new model, and he says this is the period when there are wars and revolutions. So I think this idea of reconstruction is more interesting than Kondratiev cycles as such.

Economists still debate whether Kondratiev cycles continue and on the length of the cycle. Ironically, Kondratiev cycles are the more problematic aspect of his theory and the less developed aspect of his theory than the concept of reconstruction as a necessary stage of development when one model is replaced by another. Therefore, to me the concept of reconstruction is central in my reading of Kondratiev.

Why does it figure so little in the analysis of the world system?

That is exactly the weakness of the world system analysis. In my new book, the introduction will be devoted mostly to the crisis of the world system theory or world system analysis because I think there are big problems with the world systems analysis, partly reflected by the last works of Andre Gunder Frank (ReOrient) and Giovanni Arrighi (Adam Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the Twenty-First Century). In my opinion, these are very bad as scholarly works; they reflect the weaknesses within the world system theory, which was actually moving away from Marxism and gradually dropping its links to the more traditional Marxist analysis, for which at the moment they have to pay the price intellectually.

This kind of analysis was essential to correct some of the shortcomings of classical Marxism, but it was in no way a methodology to replace Marxist analysis, but rather to supplement it. Once the world system theory tried to replace Marxism rather than supplement it, it discovered many of its own weaknesses, contradictions and gaps within itself, which it failed to refill. That was the decline of the world systems analysis, which is now the problem, and intellectually it is declining, is producing less and less material of value to understand and respond to the current crisis in global capitalism.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Boris Yulyevich Kagarlitsky (Russian: Бори́с Ю́льевич Кагарли́цкий; born 29 August 1958 in Moscow) is a Russian Marxist theoretician and sociologist who has been a political dissident in the Soviet Union and in post-Soviet Russia. He is coordinator of the Transnational Institute Global Crisis project and Director of the Institute of Globalization and Social Movements (IGSO) in Moscow.

From Frontline, Wednesday, January 12, 2011. Boris Kagarlitsky’s ZSpace Page: http://www.zcommunications.org/glob...

International Viewpoint is published under the responsibility of the Bureau of the Fourth International. Signed articles do not necessarily reflect editorial policy. Articles can be reprinted with acknowledgement, and a live link if possible.

Note: The Greanville Post publishes articles originating with Trotskyist sources but is not affiliated with any organization connected with the Fourth International.

••

NOTICE: YOUR SUBSCRIPTIONS (SIGNUPS TO OUR PERIODICAL BULLETIN) ARE COMPLETELY FREE, ALWAYS. AND WE DO NOT SELL OR RENT OUR EMAIL ADDRESS DATABASES.