JT White

(CLICK ON IMAGES TO EXPAND)

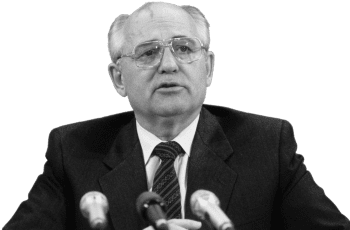

Gorbachev, with plenty of encouragement from American leaders, implemented the dismantlement of the Soviet Union, basing himself, with almost criminal naiveté, on promises the West never intended to keep.

LONDON—

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]f we wish to understand today’s Russia we have to look at the way the Federation emerged from the tumultuous collapse of the USSR. Not simply a mindless KGB thug (as he is often portrayed) Putin supported Gorbachev against his superiors and opposed the Communist attempt to overthrow Mikhail Sergeyevich and turn back the tide in 1991. The possibility of a new order was realistic in those days. Gorbachev had initiated a modicum of reform. The bloody war in Afghanistan was over. It looked as if the US might actually want a settlement on missiles. Bush had promised the Soviet leader that he wouldn’t expand NATO any further eastwards. No wonder then that the majority of Russians, along with Putin, were on the side of glasnost and perestroika.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Russian President Boris Yeltsin used this to his advantage. Fittingly, he was the right man for the time, and the wrong man for Russia. Meanwhile the Bush administration was busy backing nationalists in Yugoslavia and had adjusted its aid policy to back secession efforts, thus breaking up Tito’s dream of a state for all Southern Slavs. George HW Bush followed suit by taking the side of Russian nationalism in order to break up the Soviet Union. The “great reformer” Gorbachev had become a hindrance to be thrown on the wayside as the Bush administration aligned itself with Boris Yeltsin. The Russian people flocked to the Moscow mayor after he became a political centre of gravity for democrats in the aftermath of the botched coup. It wouldn’t last. The real agenda had little to do with democracy.

Yeltsin was as bad and as phony as Reagan for the American population. But while most Russians now see who Yeltsin was and represented, many Americans have yet to recover from the Reagan hangover.

The preference was for a selection of tiny, fractured states to succeed the USSR which could easily be picked off and subjected to economic underdevelopment. This matched Yeltsin’s personal aims for power and grandeur in the post-Cold War era. In a series of manoeuvres Yeltsin cut deals with the various leaders of Soviet republics, including Leonid Kruvchak of Ukraine, and saw the Soviet Union dissolved. Yeltsin could do this because Gorbachev had guaranteed a policy of non-intervention towards Eastern Europe. Signalling just how much the balance of power had shifted after the attempted coup, Gorbachev’s resignation was accepted pre-emptively.

This is one of the ironies of the present crisis in Ukraine. The coalition of neoliberals and ultra-nationalists who seized power form Viktor Yanukovych have done so to pull Ukraine out of Russia’s orbit and closer to the EU and NATO powers. Yet it was nationalism, followed by neoliberal prescriptions for social change, which have led to this convulsion of uprising and invasion in the first place. Recent history is evidence enough that the people of Ukraine will not ultimately benefit from events as they continue to evolve.

Shock Therapy

Gorbachev’s resignation marked the end of the Soviet era and allowed for a completely new direction. The Russian Parliament gave the President free reign to implement an economic programme of rapid deregulation and privatisation known as ‘shock therapy’. Yeltsin had the advice of economist Jeffrey Sachs and such lovers of the free-market as Larry Summers. The plan was to establish the conditions for a market society as fast as possible.

First, price controls were eliminated. The resulting hyperinflation quickly ate through the savings of most Russians. This was soon followed with a rapid privatisation of over 200,000 state-run companies. The Russian people suffered greatly for this and the rouble was tremendously devalued. Millions fell into unemployment and even those working were not guaranteed a wage as living standards plummeted. Every Russian was given vouchers to buy shares in the newly private companies. Desperate for cash, most people sold their vouchers cheaply to ruthless businessmen who began to organize the early phases of “mafia rule.” But it was just the beginning.

After a year of ruling by decree, Yeltsin’s struggles with wresting government controls from Parliament and state institutions reached a head. Apart from their effect on citizens, the privatization program had also led to a credit crunch and heavy taxes, which caused a prolonged depression. Legislative-executive tensions peaked with the 1993 constitutional crisis, when Parliament presented its own draft constitution.

The introduction of a savage, free-for-all capitalism did what the beast always does: By the end of the 1990s, 74 million Russians (more than half the population) had plunged into poverty, with 37 million of them ranked as ‘desperate’.

This quickly led to a general repeal of ‘shock therapy,’ with which Yeltsin responded by dissolving Parliament and suspending the Constitution. The Clinton administration backed Yeltsin’s decision to shell the Russian Parliament with tanks when it was occupied in protest.

After the violence, the economic reforms went further. Even more price controls were removed (going as far as to remove controls on basic food stuff like bread), state expenditure on social services was slashed, and the rate of privatization was increased dramatically. Yeltsin found his real constituents in the emergent bourgeoisie – later to be dubbed ‘the oligarchs’ – who, with his help, were wiring approximately $2 billion out of the country every month. He also undersold enormous industrial assets and resources to these people at sometimes less than 2% of their actual value.

What was the end result of all this? By the end of the decade, 74 million people had plunged into poverty, with 37 million of them ranked as ‘desperate’. Meanwhile, Moscow became the home city to more billionaires than any other city in the world.

Just like some right-wingers like too depict Obama as a communist, some Ukrainians see him as a Nazi.

By 1999, Yeltsin was a barely functioning figurehead with a coterie of close advisors and cronies around him known to the press as ‘the family’. It included oligarchs like Roman Abramovich and Boris Berezovsky. It would be this same coterie which selected Putin to succeed Yeltsin. It was appealing as the Kremlin was wracked with corruption scandals and Putin was the head of the FSB, the successor to the KGB. The oligarchs thought they could control him and use him as a battering-ram against their enemies who were looking to crack down on corruption. Putin was soon made Prime Minister. Terror attacks in Russia gave Putin the opportunity to wage war on Chechnya and boost his popularity, along with legitimizing his push for Orthodox Christian nationalism.

Putin’s Wager

Yeltsin’s resignation was secured in 1999. However, the oligarchs underestimated Putin. Rather than simply rubber-stamping the extraction of Russia’s wealth, he consolidated his position and turned on them. Putin became President in 2000 and shortly afterwards, Boris Berezovsky fled to London to escape arrest. He was soon joined by other oligarchs.

Putin smashed his old allies and set out to strengthen his position as a Hobbesian force of order and stability after the disarray of the 1990s. He has aligned himself to subservient oligarchs running the energy industry. The role of the state would now be reasserted and buttressed with tough populist appeals to chauvinism. Putin stands as the man who can flush out all the “problems” facing Russian society, whether it’s Chechen terrorists, corrupt oligarchs, or more recently homosexuals. He will also keep the factories running on schedule as an added bonus.

Now with Putin in the Kremlin the West is much more nostalgic for the days when Boris Yeltsin ran a money laundering operation out of that very building. There was never much scorn in Western governments for Russia for its savagery towards the Chechens and their bid for independence. Instead the Russian state is to be demonised for its incursions into Georgia in 2008 and, of course, Ukraine in 2014. Yet the killing of tens of thousands of people in Chechnya, since 1994, on and off, hardly gets substantive coverage in the Western media. The real problem Putin’s Russia poses for the EU and NATO is that Moscow is much less willing to accept the expansion of NATO outposts to border-states. The Russian Federation has a “rough” government, [by Western liberal propaganda ideals] but it is not feared or loathed because of its [putative] brutality, it is despised because it stands as an abandonment of Yeltsin’s market reforms and an opponent to US influence in its old backyard.

The evaporation of Viktor Yanukovich’s government was welcomed by many in Ukraine and in the West. It was not welcomed in Russia for reasons any military historian would easily grasp. Russia has long been vulnerable to Western crusades and lost 26 million people the last time the Germans went on the march. Stalin’s whole motivation to construct the Eastern bloc was to create a buffer-zone between the motherland and the Western powers. As Gorbachev’s policy of non-intervention had allowed the Eastern bloc to collapse, and had led to the chaos of the Yeltsin years, the crisis in Ukraine can only be understood as decisively post-Soviet. This is not Hungary in 1956 or Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Putin no doubt recognises what the EU wants, and how that differs to what the US wants, from Ukraine given the level of interdependence at the level of gas pipelines. The future possibility of NATO expansion to Ukraine would be completely intolerable for Putin’s government. EU membership for Ukraine may be much less outrageous, especially with Crimea as an enclave of the Russian body national. It seems plausible that the governments of Western Europe could accept the loss of Crimea to bring Ukraine into the European orbit. The American government and the German government are not going to tear apart the world economic order for Ukraine’s sovereignty. It would seem the long-term objective may be to divide the European Union from NATO.

JT White is a frequent contributor to the Third Estate and other political blogs. Founded by a group of writers and activists who met at Cambridge in the early 2000s, The Third Estate aims to offer a progressive, irreverent and atypical perspective on politics and current affairs.

NOTICE: YOUR SUBSCRIPTIONS (SIGNUPS TO OUR PERIODICAL BULLETIN) ARE COMPLETELY FREE, ALWAYS. AND WE DO NOT SELL OR RENT OUR EMAIL ADDRESS DATABASES.