[learn_more caption=”Revolutionary winds sweep over England”] The Diggers were a group of Protestant English agrarian socialists,[2] begun by Gerrard Winstanley as True Levellers in 1649, who became known as Diggers, because of their attempts to farm on common land.

real property) to reform the existing social order with an agrarian lifestyle based on their ideas for the creation of small egalitarianrural communities. They were one of a number of nonconformist dissenting groups that emerged around this time.

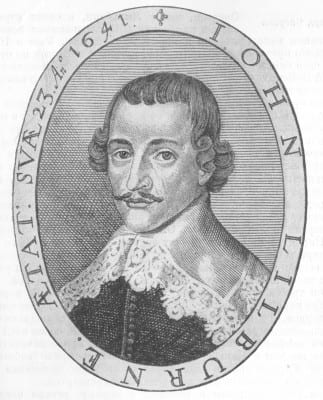

One of the greatest and bravest men of that turbulent age was John Lilburne (1614 – 29 August 1657), also known as Freeborn John. He was an English political Leveller before, during and after the English Civil Wars 1642–1650. He coined the term “freeborn rights“, defining them as rights with which every human being is born, as opposed to rights bestowed by government or human law.[1] In his early life he was a Puritan, though towards the end of his life he became a Quaker. His works have been cited in opinions by the United States Supreme Court. Why Hollywood has never found it in its collective imagination to make a film about a real life hero like Lilburne says, preferring comic book heroes or John Wayne type fantasies, says plenty about that industry’s self-imposed propaganda limits.

One of the greatest and bravest men of that turbulent age was John Lilburne (1614 – 29 August 1657), also known as Freeborn John. He was an English political Leveller before, during and after the English Civil Wars 1642–1650. He coined the term “freeborn rights“, defining them as rights with which every human being is born, as opposed to rights bestowed by government or human law.[1] In his early life he was a Puritan, though towards the end of his life he became a Quaker. His works have been cited in opinions by the United States Supreme Court. Why Hollywood has never found it in its collective imagination to make a film about a real life hero like Lilburne says, preferring comic book heroes or John Wayne type fantasies, says plenty about that industry’s self-imposed propaganda limits.

[/learn_more]

Though the Digger tradition has been celebrated by environmental activists in England, surprisingly little has been written about Winstanley’s ecology outside his native country.3Readers of Monthly Review will be familiar with the growing field of ecological Marxism, and the work of writers who argue for the fundamental incompatibility between a capitalist economic system and an environmentally sustainable human future.4 Winstanley and the Diggers also saw such an incompatibility, though from a distinctly rural and pre-industrial perspective during the development of agrarian capitalism in England. At a time when the enclosure of common lands threw vast numbers of peasants off the land and into wage labor and grinding poverty, Winstanley developed a radical philosophy that associated private ownership of land and wage labor with the exploitation and degradation of people and the earth.

Winstanley and the Diggers were unique among political groups in the English Revolution in their advocacy for the interests of the impoverished rural working classes; integral to this support was a unique concern with land use and the environment. In their constant emphasis on common access to resources for use over wasteful private consumption, True Leveller philosophy had, to use Derek Wall’s term, a “built-in ecological principle.”5 Ultimately, for Winstanley and the Diggers economic inequality and exploitation, state violence, and the destruction of the earth were deeply interrelated processes; a radical transformation in social relations—the abolition of private property and the establishment of a “free Commonwealth” based on reason and secular education—was required.

Inseparable from Winstanley’s communist philosophy, and what also helps to explain the Diggers’ continuing relevance and influence, was the group’s commitment to a specific form of praxis. The Digger communities that by the winter of 1650 had emerged throughout England were attempts to create autonomous agricultural communities for the landless poor, and their mission to reclaim the commons for the working classes has been likened to European squatter movements, the occupation of factories in Argentina and Italy, and the Brazilian MST (Landless Workers’ Movement).6 Though in some respects the experiments prefigure the utopian socialist movements of the nineteenth century in their emphasis on nonviolent social change, Winstanley’s call for a general strike in The True Levellers’ Standard Advanced (1649) and other works, and his blueprint for a communist commonwealth in The Law of Freedom (1652), demonstrate a Digger commitment to revolutionary action and transformation. Of the many radical groups that flourished during the English Revolution (including Ranters, Seekers, Anabaptists, Antinomians, Fifth Monarchists, and others), only Winstanley and the True Levellers theorized and attempted to put into practice an alternative social system not rooted in millenarian religious belief. As Winstanley put it in the summer of 1649: “Then I was made to write a little book called, The new Law of righteousnesse, and therein I declared it; yet my mind was not at rest, because nothing was acted, and thoughts run in me that words and writing were all nothing and must die, for action is the life of all, and if thou dost not act, thou dost nothing.”7

Despite their ultimate defeat, a brief exploration of the Digger movement can demonstrate how some working-class English men and women responded to the ravages of early modern agrarian capitalism, and how organic intellectuals like Winstanley rooted a critique of existing social relations in a radical plebeian ecology. In so doing the True Levellers can contribute to the growing historical literature on ecosocialism, and at the same time provide inspiration and ideas to new generations of activists. At a time when the appropriation of the earth and indigenous knowledge for private profit is accelerating, and the global working classes are struggling to construct viable socialist alternatives, it is worth revisiting the theory and practice of what was the first organized anti-capitalist movement in history.

Origins and the English Revolution

In the spring of 1607, thousands of people in the Midlands of England rose to prevent the enclosure of their common lands. Participants (mainly rural laborers, artisans, and small farmers) referred to themselves collectively as “diggers” and “levellers”—up to that time terms of elite derision and contempt.8 Anti-enclosure riots were not, however, new to the early seventeenth century. Large-scale popular opposition to enclosing (the privatization of common lands) and engrossing (the amalgamation of two or more farms into one) dated to the fifteenth century. The conversion of arable to pasture land with the expansion of the cloth industry, a rapidly growing population, and changing class relations in the sixteenth century signaled the rise of agrarian capitalism in the English countryside.9 It is often forgotten that Thomas More’s Utopia (1516) was in large part a work of social criticism aimed at landholders who enclosed the commons for the production of woolens. The idle English nobility and gentry enclosed all land possible, leaving nothing for food production. Former tenants whose labor was no longer needed in the fields were forced to wander, beg, or steal for their survival, and many found themselves unemployed in “hideous poverty.”10 Though More himself was no revolutionary, popular rebellions were a constant feature of Tudor society, as a new class of capitalist yeomen emerged at the expense of the traditional nobility and peasantry.11 The revolts of 1607 were part of a long tradition of peasant protest in England; four decades later the Diggers would take this tradition in a dramatically new direction.

The English Revolution was a complicated affair. Most traditional accounts emphasize the political and religious conflict between Parliament and King Charles I, with the execution of the king in 1649 followed by a period of political instability that ended with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Yet the century preceding the outbreak of war witnessed dramatic economic and religious change in England. King Henry VIII’s establishment of the Anglican Church in 1536 was accompanied by the dissolution of the monasteries, which led to the systematic transferal of property that benefitted large landowners and the royal state.

Between 1580 and 1620 the enclosure movement resulted in a massive upward redistribution of wealth, while the 1590s and 1630s were decades of severe subsistence crises. The years 1646–1650—the period that witnessed the creation of the Digger movement—saw the worst run of bad harvests of the seventeenth century, as well as the lowest real wages for working people; starvation was reported in the north of England.12 Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England saw the unprecedented creation of nationwide laws that legislated wages, apprenticeship, and poor relief; over the same period numerous petty crimes against property were made punishable by death.13 By the middle decades of the seventeenth-century England’s social, economic, legal, and religious landscape had been profoundly transformed.

The first Diggers’ colony appeared on St. George’s Hill near Cobham, Surrey at the beginning of April 1649, seven years after the outbreak of civil war and two months after the beheading of Charles I. Though initially just five Diggers began to plant “parsenipps, and carretts, and beanes” on the admittedly barren commons, their numbers grew thereafter. From such modest beginnings it was envisioned would emerge a revolutionary movement, for the ultimate goal of the Diggers on St. George’s Hill was no less than to make the earth a “Common Treasury” for all, through shared agricultural labor on commonly held land. The Diggers would thus till the commons and wastes of England collectively; withdrawing their labor from commercial society they would decommodify social relations and establish the True Levellers’ relationship with the earth. Once the common people saw the success of the Digger experiment, they would refuse to labor for wages any longer, and would work to create free associations of communist commonwealths in England and throughout the world. By “labouring in the Earth in rightousnesse together,” the True Levellers intended to “lift up the Creation from that bondage of Civill Propriety, which it groans under.”14

Officials and writers were unsure what to make of the small group of radicals digging on St. George’s Hill. The Royalist newsbook Mercurius Pragmaticus made fun of “Prophet Everet’s”—a reference to William Everard, an early leader of the Diggers—intention to convert “Oatlands Park into a Wildernesse, and preach Liberty to the oppressed Deer,” while implicitly acknowledging the group’s potential threat to social order.15 Though officials of England’s New Model Army concluded the Diggers were not at that time a serious threat, some local residents commenced attacking the group almost immediately. Local lords like Francis Drake and freeholders organized gangs to attack the commune, and Winstanley responded in writings addressing the persecution and specious arrests for trespassing leveled against the Diggers. Despite incarcerations, the pulling down of houses, and the destruction of their spades and hoes, Digger numbers continued to grow. Yet finding local courts on the side of their oppressors, the group was forced to abandon St. George’s Hill in August of 1649, just five months after the digging commenced.16

The Diggers then moved to nearby Little Heath in Cobham, where they cultivated several acres of land, a number of houses were built, and new pamphlets were composed. Local hostility at Little Heath was less marked than at St. George’s Hill, as a number of Diggers had ties to the community and the parish of Cobham, and a history of local social tensions may have contributed to popular sympathy for the True Leveller colony. Yet official repression was more pronounced in Cobham than at St. George’s Hill; in October the community was harassed by local officials, and in the following month Digger houses were again pulled down by soldiers and organized thugs. Though local gentry, supported by justices of the peace, the county sheriff, and detachments of soldiers led a highly organized campaign against the group, they were unable to mobilize local commoners against the colony. As Digger communities in other parts of England sprouted into existence, the Little Heath group began to thrive—despite repression and a particularly brutal winter in 1649–1650. Yet their financial resources were dwindling, and in March 1650, as the Commonwealth government became increasingly concerned over the revolutionary social experiments being conducted by Diggers, the Council of State sent a military detachment to disband the community at Cobham, while other True Leveller colonies were also suppressed. In the midst of numerous legal actions against the Little Heath Diggers—including indictments for riot, trespass, illegal assembly, and the illegal erection of cottages—the radicals at Cobham disbanded in the summer of 1650.17

Winstanley’s most important works were composed under substantial duress over the short period of 1649–1650. Despite severe persecution, the True Levellers paradoxically sought a restoration of humankind’s natural equality by engaging in a dramatically new social experiment. As Winstanley formulated his unique vision, Diggers attempted to establish autonomous agricultural communities on the commons of England, to sustain themselves free of market relations, and to demonstrate to the laboring classes throughout the world that the power to emancipate themselves from slavery existed in this world. Whatever the practical limitations of the communities (and there were many—not least their mistaken belief that the ruling class could be persuaded voluntarily to relinquish its dominion), the Digger colonies show how common people could, through direct action and cooperation, formulate a radical alternative to existing social relations.

Winstanley’s Ecology

Though the Digger experiments were in large part a response to profound socio-political and religious crises, Winstanley’s ideas were formulated during a period of unprecedented cultural and intellectual ferment. As official censorship of the press in England lapsed in 1640 (only to return with the monarchy in 1660), common people for the first time were able to publish criticisms of the state and the official Anglican church, while interpreting religious doctrine in new, more egalitarian, ways. Although critics like the Puritan supporter of Parliament Thomas Edwards denounced the “Ecclesiasticall Anarchy” resulting from “all sorts of illiterate mechanick Preachers, yeah of Women and Boy Preachers,” what were traditionally subterranean anti-clerical beliefs among the common people were nonetheless expressed openly for the first time during the 1640s.18 In addition to the anti-hierarchical religious views of groups like Anabaptists and Seekers, anonymous early Digger petitions like Light Shining in Buckinghamshire (1648) would influence the development of Winstanley’s thought—particularly the notion that “inclosers” had historically monopolized the earth’s natural bounty, creating inequality and class oppression among humankind.19 Winstanley, however, diverged from other radicals of the revolution in his novel interpretation of the relationship between the environment, property, social relations, and how to remedy the injustices that pervaded the world.

The idea that God had given mankind dominion over the earth and its creatures, and that the fall of man destroyed the natural equality of Eden,20 were truisms for most people in early modern Christian Europe. Though Winstanley, like many radical Protestants of the time, drew on these beliefs, his religious views were highly unorthodox, and would have been punished as heretical in earlier periods. His use of the Bible was often allegorical, and his allegories were filled with natural imagery; the Garden of Eden, for example, was the inward spirit of humanity which had been filled with weeds—pride, envy, covetousness, and hypocrisy.21 From his earliest pre-Digger writings Winstanley also displayed a tendency towards a pantheism that would significantly shape his ecological outlook in later writings. These initial leanings were influenced by the belief in some radical circles (notably among Seekers, whose beliefs foreshadowed those of the Quakers) that God—or Reason, Winstanley’s substitute for God—dwelled within all human beings and throughout the natural world. In the pre-Digger work The Breaking of the Day of God (1648), Winstanley stressed that humankind was part of “one flesh, or one earth,” and that heaven was not to be sought in the skies as the histories had written. Rather, heaven could be found wherever God dwelled—which was to say, in every part of the material world.22 Early in 1649, prior to the establishment of the Digger colony on St. George’s Hill, Winstanley wrote that before the existence of private property and hierarchy “every creature walked evenly with man, and delighted in man, and was ruled by him; there was no opposition between him and beast, fowls, fishes, or any creature in the earth.”23

Winstanley’s Digger writings nonetheless diverged in important ways from his early works. Most importantly, his increasingly materialist orientation brought about a rethinking of humans’ relationship with each other and the earth—which necessarily led to the idea that liberation must come in this world. The foundation of these ideas were laid in the first Digger manifesto in 1649, The True Levellers’ Standard Advanced. Here it is revealed that in the beginning of time the “great creator Reason” made the earth to be “a common Treasury of relief for all, both Beasts and Man.” With the invention of private property, classes were created, establishing societies in which the majority labored in servitude and slavery for a minority that monopolized the land and goods it produced. Utilizing biblical evidence and symbolism, and dividing history into seemingly millenarian epochs (with great emphasis on the Norman conquest of England in 1066), Diggers declared their intention to liberate both humankind and the earth from the oppression of the ruling order: “we have now begun to declare it by action in digging up the common land, & casting in seed that we may eat our bread together in righteousnesse.” The figurative way in which Winstanley used the Bible, and the extent to which ecology informed Digger belief, was demonstrated in the Standard’s injunction to honor thy father and mother.24 Father here symbolized the “Spirit of Community,” while Mother was “the Earth, that brought us all forth.”25 Religion was by this time useful largely as an educative device; community and the earth had taken primacy in Winstanley’s now thoroughly materialist philosophy.

Traditional religious belief also stressed that with the Fall and the expulsion from the Garden of Eden the curse of labor was inflicted on humankind by a vengeful God.26 Though a popular belief in the dignity and virtue of honest labor had existed for millennia, Winstanley turned many traditional Judeo-Christian beliefs regarding labor on their head. For the Diggers the physical act of labor was no longer a painful reminder of humankind’s sinful fall from grace. On the contrary, “labouring the Earth in righteousnesse” collectively, without wages, would liberate humans and the earth from oppression and the bondage of individual ownership. More radical still, the Standard recognized labor’s contribution to wealth/value, stressing that “the poor by their labour lifts up tyrants to rule over them,” as riches were transferred from producers to the thieves of labor’s produce. Winstanley therefore called on all those who labored for wages to refuse to work any longer, in effect demanding self-emancipation of the laboring classes through a general withdrawal of their labor (i.e., a general strike).27 At the root of this critique and call to action was the materialist notion that as Mother Earth brought forth all creatures, so all, “according to the Reason that rules in the Creation,” had an equal right to the fruits of the land. The True Levellers were self-consciously attempting to put into practice a program of liberation based on challenging deprecatory traditional beliefs regarding the “curse” of labor. Laboring in common for subsistence and comradeship was in fact “righteous,” and was associated with “universall Liberty and Freedome,” rather than with human sin and punishment.28

Winstanley continued to develop the ideas first expressed in the The True Levellers’ Standard Advanced over the following year, despite the severe repression experienced by the Diggers on St. George’s Hill and at Little Heath.29 The most complete expression of Winstanley’s evolving materialist philosophy was published in 1652, however, after the successful elimination of the Digger communities. The Law of Freedom was a blueprint for what Winstanley termed a “free Commonwealth,” in contrast to the “Kingly Government” that still prevailed in England, despite the execution of Charles I in 1649. Many Digger themes were evident in the work: the rich had obtained their wealth through the oppression of the laboring classes, after the appropriation of the earth had led to the establishment of class society and legalized domination. Official religion and ideas about heaven and hell were the creation of a national ministry designed to keep the people in ignorance and fear. The communist commonwealth would restore true freedom, and this freedom was rooted in Digger earth ecology: “True Freedom lies where a man receives his nourishment and preservation, and that is in the use of the Earth.”30 Since private property had created oppression and exploitation, as one part of an interrelated ecological system the liberation of human society required the deliverance of the earth from the bondage of individual ownership. And, though his treatise was famously dedicated to Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England, Winstanley stressed that with the abolition of private property the people would be sovereign; the Commonwealth’s leader (at the time of the Rump Parliament) was vividly reminded that “The Earth wherein your Gourd grows is the Commoners of England.”31

The originality of the Law of Freedom lay in its program for a secular society characterized by equality, democracy, and a spirit of free inquiry. The work is also a complex mixture of hope and despair—the Digger communities had been destroyed, and Winstanley stressed to Cromwell that now “I have no power.” Though scholars have pointed to the patriarchal and harsh disciplinary measures evident in the work, it should be kept in mind these were rational, if severe, responses to anticipated criticisms from a dominant culture obsessed with “idleness” and social order.

In contrast to social convention, in the free Commonwealth women would marry whom they desired, and throughout his writings Winstanley, like the Quakers after him, was far more radical than most contemporaries in arguing for woman’s natural equality with man.32Although in the free Commonwealth those unwilling to labor would be forced to work, the “idle” from the popular perspective were not the poor and unemployed; they were traditionally the “rich men” who lived at ease, “feeding and clothing themselves by the labors of other men.” Production in the free Commonwealth would be organized along uniquely democratic lines. Regulators of crafts and agriculture would oversee a system of apprenticeship, and these overseers would be annually elected by the workers themselves, “to prevent the creeping in of Lordly Oppression.”33 If an earlier Digger call for working-class self-emancipation was necessarily absent, Winstanley’s consistent hostility to class society and exploitation were expressed in a new blueprint for a society based on equality and democracy.

Similarly revolutionary was the Law of Freedom’s educational system, which was rooted in experimental science, human reason, harmony with nature, and the widespread dissemination of knowledge. Private property and the exploitation of natural resources were in fact linked to the historical suppression of knowledge. If “the Earth were set free from Kingly Bondage,” and all were guaranteed a livelihood, the wonders of nature “would be made publike” instead of being monopolized by professors; with the establishment of the free Commonwealth knowledge will “cover the Earth, as the waters cover the Seas.” In keeping with Winstanley’s uncompromising anti-authoritarianism, a class of educated professionals was anathema, for the gatekeeper of information was “he who puts out the eyes of man’s knowledge, and tells him he must believe what others have writ or spoke, and must not trust to his own experience.” “Ministers” (like the overseers of trades and agriculture) would be elected annually; they would deliver secular lectures on history, law, and the sciences—though all would be free to address topics involving knowledge of the earth and movement of the stars and planets. Understanding of the material world was fundamental, for in nature “all true knowledge is wrapped up.”34 Winstanley’s plan for a communist commonwealth combined an absence of private property and exploitation, respect for the natural world, and an educational system whose focus was rational scientific inquiry rather than superstitious speculation. Rooted in his radical ecological vision, the True Leveller’s last published work sought to lay out a vision based on substantive social and environmental justice.

The Diggers’ Contemporary Relevance

In 2010 the World Peoples’ Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth adopted the “Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth,” and submitted it to the United Nations for consideration.35 Though the English Revolution occurred prior to the emergence of eighteenth-century Enlightenment discourses regarding natural rights, many of the issues emphasized in the Declaration resemble in fundamental ways ideas articulated by Winstanley and the Diggers in the late 1640s. The interrelatedness and interdependency of all living things, and the fundamental incompatibility of capitalist social relations with a sustainable and peaceful future for humankind emphasized in the Declaration’s preamble, would not have sounded strange to True Levellers. In contrast to a dominant view in early modern Christian Europe regarding human’s dominion over the earth and its resources, the Diggers, like the People’s Conference, recognized that “Mother Earth is the source of life, nourishment and learning and provides everything we need to live well.” Diggers’ call for the recognition of the earth as a common treasury, and for the “Birthright” of “universall Liberty and Freedome” among all peoples, presaged modern rights ideas in ways worth revisiting.36

C.B. Macpherson wrote that what distinguished Winstanley and the True Levellers or Diggers from the Levellers was “Winstanley’s utopian insight that freedom lay in free common access to the land. For Winstanley that was the key to freedom, for that was the only way to assure freedom from exploitation of man by man. The only natural right of the individual that Winstanley recognized was the natural right of men to labour together and live together, governing themselves according to a natural law of self preservation.”37

The Digger experiments and the ideas of Winstanley are also relevant in their call for self-organization among the working classes, and for emphasizing the intelligence and dignity of commoners often portrayed by elites as needing guidance and discipline. Liberation, as Winstanley frequently claimed in his Digger writings, would only come when working people throughout the world (not just in revolutionary England) withdrew their labor from market society, and set up a social system in which exploitation and poverty no longer existed. Winstanley frequently responded to elite criticisms regarding the emergence of “mechanick preachers” during the 1640s by noting that the biblical scriptures were written by “the experimentall hand” of shepherds, farmers, fishermen, and others of the laboring classes.38With the Law of Freedom, Winstanley made clear the radical democratic elements of his philosophy in his call for a secular education for all citizens of the commonwealth. In their revolutionary ideology, rooted in a radical ecological vision and centered on the self-emancipation of the oppressed through “righteous” collective labor and the sharing of knowledge, the Diggers have much to offer modern ecosocialist theory and practice.

Notes

- ↩The scholar whose work is most associated with the Diggers is the great British Marxist historian Christopher Hill, though in recent years John Gurney has done much important research. For the anarchistic elements of Winstanley’s philosophy see George Woodcock, Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (Cleveland: Meridian, 1962).

- ↩Diggers’ influence on environmental activists in England is summarized in Ariel Hessayon, “Restoring the Garden of Eden in England’s Green and Pleasant Land: The Diggers and the Fruits of the Earth,” Journal for the Study of Radicalism 2, no. 2 (2008): 9–10, though despite its title this article fails to seriously engage with Winstanley’s ecology.

- ↩The work of John Bellamy Foster, Brett Clark, Richard York, Fred Magdoff, Paul Burkett, and Chris Williams is essential.

- ↩Wall, The Rise of the Green Left: Inside the Worldwide Ecosocialist Movement (London: Pluto Press, 2010), 58.

- ↩Paul Chatterton and Stuart Hodkinson, “Why We Need Autonomous Space in the Fight Against Capitalism,” http://trapese.clearerchannel.org.

- ↩Gerrard Winstanley, The Complete Works of Gerrard Winstanley, 2 vols., edited by Thomas N. Corns, Ann Hughes, and David Lowenstein (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 2: 80.

- ↩Thomas More, Utopia, in Stephen Greenblatt, et. al., eds., Norton Anthology of English Literature, 9th revised edition, (New York: W.W. Norton, 2012), 531-32.

- ↩Christopher Hill, Liberty Against the Law: Some Seventeenth-Century Controversies (New York: Penguin, 1996).

- ↩Winstanley, Complete Works, 2: 10, 13–14.

- ↩Quoted in Gurney, Brave Community, 122.

- ↩Gurney, Brave Community, 166–96.

- ↩Thomas Edwards, Gangraene (1646), preface, http://archive.org.

- ↩Light Shining in Buckinghamshire (1648), http://marxists.org.

- ↩Genesis 1:26, and Genesis 3:1–24.

- ↩Winstanley, Complete Works, 2: 172.

- ↩Ibid, 1: 118, 177, 421.

- ↩Ibid, 1: 478, 489, 92.

- ↩ Exodus 20:12.

- ↩Though Winstanley was clearly the author of The True Levellers’ Standard, Advanced it was signed by fourteen other Diggers, suggesting possible collaboration in the project. Winstanley,Complete Works, 2: 1, 4–5, 15, 18.

- ↩ Genesis 3:17–19.

- ↩Winstanley, Complete Works, 2: 9, 10, 13.

- ↩Winstanley, Complete Works, 2: 295.

- ↩Ibid, 2: 280.

- ↩Ibid., 2: 288–89, 302–3, 325–27.

- ↩Ibid., 2: 340–44.

- ↩For the entire text of the “Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth” in English, see http://climateandcapitalism.com.

- ↩ C.B. Macpherson, The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962), 157.

-