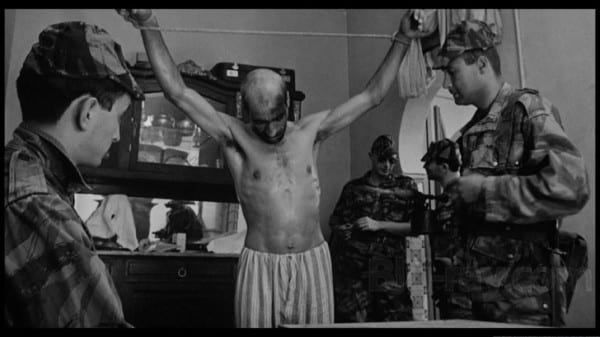

The French “paras” arrive to settle the insurrection in Algiers, by any means necessary. (Screen grab from The Battle of Algiers, 1966, by Gillo Pontecorvo.)

Aussaresses in his prime. (French Wikipedia). The caption reads: “Paul Aussaresses, (1918-2013), général de l’armée française. Parachutiste, il est connu pour son utilisation de la torture pendant la guerre d’Algérie, en particulier lors de la bataille d’Alger.”

Aussaresses stated that the French government insisted that the French military in Algeria “liquidate the FLN (Front de Liberation Nationale) as quickly as possible.” Following the controversy fueled by his statements, he was stripped of his rank, the right to wear his uniform and his Légion d’honneur. (See special section below)

Don’t miss the classic film The Battle of Algiers, directed by Gillo Pontencorvo, in the Appendix. The best reconstruction in the history of cinema of a revolutionary insurrection against colonialism.

SPECIAL: READ THE WASHINGTON POST OBIT OF GEN. AUSSARESSES, NOTABLE BECAUSE THE WRITER CLEARLY STATES THAT THE ALGERIAN REBELLION WAS SPARKED BY THE BRUTAL COLONIAL ABUSES OF THE FRENCH.

The account however does not dwell at all on the role played by Aussaresses as an adviser to Latin American dictatorships in the use of “dirty war” methods. Still, the admission that the rebels were acting as a result of legitimate grievances is something of a novelty and is not exactly normal for American media, especially the WaPo, a cynical instrument of US imperial policy. Click on the bar below.

THE WASHINGTON POST

Paul Aussaresses, a French army general who in the final years of his life dispassionately revealed the torture techniques he employed during the Algerian war for independence and defended them as appropriate measures in the modern age of terrorism, has died. He was 95. His death was announced Dec. 4 by a French veterans’ association. No details were provided.

Paul Aussaresses, a French army general who in the final years of his life dispassionately revealed the torture techniques he employed during the Algerian war for independence and defended them as appropriate measures in the modern age of terrorism, has died. He was 95. His death was announced Dec. 4 by a French veterans’ association. No details were provided.

Gen. Aussaresses spent nearly his entire career in the service of his country’s military. He was described as a hero of World War II and fought in the French Indochina War before being posted to Algeria at the outset of the anticolonial rebellion there in 1954. The insurgency raged on until Algeria gained its independence in 1962.

Five decades later, the war and its prosecution remain the subject of intense soul-searching in France, much as the Vietnam War continues to weigh on the American psyche. Gen. Aussaresses was chief of French military intelligence during the Battle of Algiers, the uprising in the Algerian capital in 1956 and 1957. Working under French Gen. Jacques Massu, he helped put down the guerrillas who had been radicalized by past abuses perpetrated by their colonial rulers.

The rebellion continued in other regions, however, and the French victory in Algiers came to represent the folly of winning a battle but losing the war. In 2001 — long after his retirement — Gen. Aussaresses made international headlines with the publication in France of a memoir later translated in English as “The Battle of the Casbah: Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism in Algeria 1955-1957.” The book detailed the torture and summary executions in which he had taken part, and they provoked an uproar in France.

Then-President Jacques Chirac said in a statement at the time that he was “horrified” by the book’s contents. “The methods I used were always the same: beatings, electric shocks, and, in particular, water torture, which was the most dangerous technique for the prisoner,” Gen. Aussaresses wrote. “It never lasted for more than one hour and the suspects would speak in the hope of saving their own lives.” He wrote that he was “indifferent” to the executions of his adversaries and that some deaths were concealed as suicides. “If I myself went on to carry out these summary executions,” he had once told an interviewer, “it was because I wanted to assume personal responsibility. I didn’t want to make someone else do the dirty work.”

Gen. Aussaresses contended that French government officials, including then-justice minister and future president François Mitterrand, were aware of and condoned the use of torture in Algeria. Confronted by international outcry, Gen. Aussaresses insisted on the rightness of his actions. “I express regrets, regrets, regrets,” he told the Associated Press. “But I cannot express remorse. That implies guilt. I consider I did my difficult duty of a soldier implicated in a difficult mission.”

Writing in the New Republic, the human rights and international affairs scholar Michael Ignatieff argued that the book was notable not for its specifics but for the author’s perception of their meaning. “What was distinctive about Aussaresses,” Ignatieff wrote, “was his jaunty impudence about the whole issue, his insistence that he had no regrets and that he would do it again in the context of the contemporary war on terrorism.” Months after the release of the book, and amid intensifying national outrage, Gen. Aussaresses was charged in a French court with “complicity in justifying war crimes.” He stood trial for having been an apologist for the torture techniques — not for having used them, as long-standing amnesty legislation protected French veterans of the Algerian conflict. Gen. Aussaresses was convicted and fined the equivalent of about $6,000. His publishers were fined about twice that amount. He was stripped of his Legion of Honor award.

Amid the drama of the trial, Gen. Aussaresses was interviewed by “60 Minutes” newsman Mike Wallace. Wallace asked him if Zacarias Moussaoui, a conspirator in the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, should be tortured for information. “It seems to me,” Gen. Aussaresses replied, “it is obvious.”

Gen. Aussaresses was born on Nov. 7, 1918, in Saint Paul Cap de Joux, in southern France, and trained at the Saint-Cyr military academy. He was an officer cadet in Algeria during World War II before joining the Free French Forces and parachuting to the aid of French resistance fighters in German-occupied territory in Europe. Gen. Aussaresses wore a patch over his left eye. At least one newspaper over the years reported that he had lost the eye during the war. At the time of his death, however, the Associated Press reported that the cause had been a failed cataract surgery.

After his assignment in Algeria, he was a military attache in Washington and lectured U.S. Army Special Forces at Fort Bragg, N.C., according to the Encyclopedia of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency. He later was an adviser to Latin American governments.

Gen. Aussaresses was reportedly married twice and had several children. A complete list of survivors could not be confirmed. He acknowledged that many observers wanted him to display repentance but said that he could not. “If tomorrow and every day bombs went off in Paris stadiums, cafes, or elsewhere, do you think the government and police would fight back with classic means?” he said. “When one has seen, like I have, civilians, women, children, dismembered or nailed to a door, you are marked for life.”

Emily Langer is a reporter on The Washington Post’s obituaries desk. She has written about national and world leaders, celebrated figures in science and the arts, and heroes from all walks of life.[/learn_more]

APPENDIX