The “Stalin Question” lives on

THE STALIN QUESTION

=By= Steve Jonas

(with additional commentary by Michael Faulkner)

The truth about the Stalin period, still debated in the light of new historical findings, and the enormous accumulated weight of countless layers of hostile propaganda, is essential to the discussion of humanity’s options if it is ever to escape the clutches of capitalism.

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]irst let me say that I have never wavered in my belief that if a) the human species is to survive and b) the world is to be made a better place for all living things, the political/economic system called capitalism — based on the private ownership of the means of production, operated by the owners primarily for their own benefit with the principal focus being on the accumulation of profit and capital, must someday be replaced by some form of socialism — a political/economic system in which there is common ownership of the means of production, operated in order to produce the greatest good for the great number.

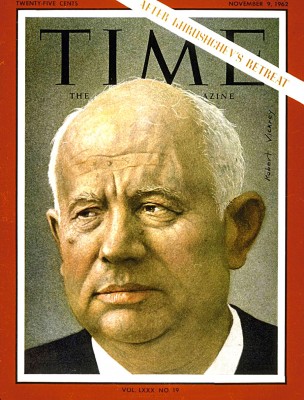

BELOW: Khrushchev’s denunciations shook the party’s rank and file around the world and gave ammunition to socialism’s class enemies, but some of his criticisms have also been questioned. The Soviet period between the two world wars is certainly one that refuses to accept black and white characterizations.

The mode of ownership of the means of production is key. This is because the human species is the only one which requires for its survival the conversion of elements found in the environment into goods and services of a different nature. It is the mode of ownership of the means of conversion, otherwise known as the relations of production, what is done with any surpluses that are produced, and who owns the outcomes of production in the first instance, which defines the nature of the society.

The mode of ownership of the means of production is key. This is because the human species is the only one which requires for its survival the conversion of elements found in the environment into goods and services of a different nature. It is the mode of ownership of the means of conversion, otherwise known as the relations of production, what is done with any surpluses that are produced, and who owns the outcomes of production in the first instance, which defines the nature of the society.

Now, there are many people around the world who generally agree with this proposition but look at, or have looked at, the Soviet experiment and have said something like “nah, it can never happen; Stalinism proved that socialism cannot work and never will.” Thus we have to think of something else {although except for various forms of anarchy and “self-determination” no one seems to have come up with anything that a) might have a chance of seizing the ownership of the means of production from the capitalists who are not, as they have displayed over-and-over again since 1917, not going to give up without one helluva fight, and b) might have a chance at operating an increasingly complicated advanced industrial society.

Well, first I say to such claims “let’s take a look at Oliver Cromwell and the English Civil War.” This was the first armed conflict in history that attempted to replace the feudal order of society with one based on mercantile capitalism. In short, the Cromwellians lost. Now one who liked the general idea of mercantile capitalism could have said, “Ah me, the war is lost; feudalism will never be replaced; we might as well just accept it.” Or they might have said, “you know, this was just the first step. I see another revolution coming [which would be the Glorious Revolution of 1688] and then perhaps mercantile capitalism will really take off.” It is unlikely that they would have, at that time, also anticipated the Industrial Revolution that began in the 18th century and directly led to industrial capitalism, but hey, you never know.

[box] The American media often mirrors accurately the attitude of US ruling circles toward specific subjects, leaders or political systems. In the covers below, Time Magazine, one of the nation’s pre-eminent opinion-shapers, cues the audience on its evolving views of Stalin. In the first cover, on the left (1933), the magazine is already characterizing Stalin as a cold-blooded mass murderer. In the center image (1942), during the short-lived WW2 antifascist alliance, the Soviet leader is depicted in neutral terms, with subtle admiration for his troops, clad in winter garb. By 1953, with Stalin recently deceased, the propaganda slant is back, depicting the Kremlin as a ruthless web of spiders. (Click on images for maximum resolution.) [/box]

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]hen I like to cite the famous quote from Leon Trotsky (nee Lev Bronstein) that “Stalin would be the grave-digger of communism,” and the Lenin Testament that warned against his takeover of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). [Communists never ascend to power by normal, rightful means, supported by the masses; in US propaganda playbooks, they always “take over”.—Ed]

…

Stalinism was NOT the inevitable outcome of the Russian Revolution. As suggested to me by my long-time English friend, colleague, and historian/political scientist with a special interest in 20th century Germany and the Soviet Union, Michael Faulkner, whose columns are now published regularly on The Greanville Post, in some of the many discussions/exchanges of opinion we have had on this subject: “the view that it is was held by both Stalinists and hard-line anti-communists. The former approve of it and accept it as true socialism and the latter excoriate it and warn that this is where all socialist revolutions must lead. The outcome of the debates in the Bolshevik party in the late 1920s was by no means a foregone conclusion.”

(LEFT) “Long live Stalin’s air force!”, proclaims this wartime poster, in 1943. The cult of personality was already an accepted fact of life.

(LEFT) “Long live Stalin’s air force!”, proclaims this wartime poster, in 1943. The cult of personality was already an accepted fact of life.

As detailed by Nikita Khrushchev in his very important book, Khrushchev Remembers, (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1970), Stalin committed many crimes. He did not believe in the Leninist principles of collective leadership and Democratic Centralism. He came to believe that in order to stay in power and see his politics through he had to silence anyone who disagreed with him. For one reason or another, by one means or another he was able to gather about him a body of armed men and back them up with a rigged “judicial” system, who/which would do his bidding no matter what. It is ironic that it was “special bodies of armed men” that Lenin described as central to state control for whichever class happened to have control of the state apparatus.

Michael Faulkner has added the following thoughts on this matter: “I don’t think that Stalin was deeply interested in a vast accumulation of personal power and therefore I don’t think it is appropriate to think of him as a dictator in that conventional sense. He was (or at least regarded himself as) a Marxist and a dialectical materialist, for whom what he called “Marxism-Leninism’ was the ideology determining his existence. As you know, he invented the phrase. [Functionally] he was a dictator nevertheless. By the early 1930s at the latest he had probably come to regard himself as the ultimate guardian and trustee of the October Revolution. He may have kidded himself that he operated a system of ‘collective leadership’ but by the end of the 1930s, after the purges, he had eliminated all real and imagined opposition. He had come to believe that through his superior grasp of the theory and practice of ‘class struggle’ the destiny of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ rested entirely on his shoulders.”

For Stalin, of course, “silencing” his opponents eventually came to be killing them. Thus Stalin, over the years, killed off many of the best potential civilian and military leaders of the CPSU and the nation as well as many of the best rank-and-file members of the Soviet Communist Party. So the killing was not just a horrendous crime in itself, but it was also a crime in terms of the future of the nation.

Stalin’s other major crime was his failure to prepare the nation for the Nazi invasion in 1941, for which he was given ample warning, both by his own intelligence services and by deserters from the Wehrmacht build-up that was taking place along the then-border between the Soviet and Nazi German “General Gouvernement” portions of Occupied Poland. Because of this he was responsible for many unnecessary deaths, both civilian and military, and much destruction in the Soviet territory that would eventually be occupied by the forces of the Third Reich.

However, unlike the other Great Dictator of the period, Adolf Hitler, for one reason or another, Stalin was able to delegate enough of the major military decision-making to the generals of his who survived the Purges of the late-30s, so that the equivalent of the series of disastrous military mistakes that Hitler made from the time of the Battle of Moscow in December, 1941 onwards, was avoided.

At the same time, it is impossible to know whether or not without Stalin’s control of the Party and the Government in the 1930’s, the forced farm collectivization which was absolutely necessary for the forced industrialization which was absolutely necessary for the military build-up which did, along with the heroism of the Soviet military and civilian populations, eventually lead to the total victory of the allies over Nazi Germany, would have occurred.

Michael Faulkner adds: “He believed totally in ‘socialism in one country’ and also in the inevitability of capitalist encirclement and the eventual invasion by one or more capitalist powers. In 1931 he predicted that ‘We are 50 to 100 years behind the advanced capitalist states of the West; we have 10 years to catch up. We shall either succeed or go under.’ That was meant in earnest. . . If Stalin had not been in power, would there have been a forced march of collectivization and industrialization at all?

“Under an alternative leadership (e.g.) Nikolai Bukharin, could there have been collectivization and industrialization either without force, or at least without the tyrannical use of force which characterized the Stalinist method? If such an alternative had been adopted, could it have achieved similar results in the 10 years available before the Nazi invasion of 1941? Questions like this, hypothetical though they may be, are important. If the answer is that there was no alternative to the Stalinist forced march (and let’s not forget what the enormous cost was in human lives, political terror and the decimation of a whole generation of Bolsheviks), then we have to admit that without Stalin and Stalinism there could have been no victory over Nazi Germany. However, if that was the price that had to be paid it is not easy to accept that the regime that triumphed over Nazism was in any sense that we might want to recognize, a socialist regime.”

Finally, in understanding the failure of the Soviet experiment in general and Stalinism in particular, one has to understand that Stalin, his predecessors and his successors, were all operating within the context of the “75 Years War Against the Soviet Union,” led before World War II by the United Kingdom, France, and Nazi Germany, during the War by Nazi Germany, and after the War by the United States. It is highly unlikely that in that context, regardless of the leadership, once the United States had decided in the early 1960s not to accept any form of Khrushchev’s offer of “peaceful co-existence,” any form of the Soviet Union could have survived.

One major task for future socialists, having assumed the leadership of the political/economy of a given country, is to figure out how to make sure that individual dictatorship, even socialist individual dictatorship (which is different from the Marxist concept of the “dictatorship of the proletariat”), with the potential concomitant development of the Cult of Personality (which happened in China too), does not occur. That is of course a task for another time and space. But one can establish the principles of government on which the outcome would be based. There needs to be an enforceable Constitution with meaning. The Soviet Union had one, but no one in the government or the Party paid much attention to it. There has to be a means for the prevention of the concentration of power in the hands of one person, which means that there has to be true collective leadership on the Leninist mode (much easier said than done, in a revolutionary or immediate post-revolutionary situation). Finally, under overall Party leadership, there still, at some meaningful level, has to be separation of powers (I think). MUCH easier said than done, and I shall thus leave it here.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Both Steve Jonas and Michael Faulkner, men with a multidisciplinary background ranging from medicine to academia, serve as senior contributing editors to The Greanville Post. Besides The Greanville Post, their articles are also published widely on several other prominent political blogs, including OpEdNews, TPJ, and Buzzflash. Further details about their background can be read on our editors bios page.

What is $1 a month to support one of the greatest publications on the Left?