Nina Kouprianova | Center for Syncretic Studies

“There are no separate Russia or Ukraine, but one Holy Rus” – Elder Iona of Odessa

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he year 2014 saw an unprecedented surge of patriotism in contemporary Russia, which resulted in popularizing the notion of the Russian World. One reason for increased patriotic sentiment was Crimea’s return to the home port after the overwhelmingly positive vote by its majority-Russian residents in a referendum one year ago.

CLICK ON IMAGES TO EXPAND TO MAX RESOLUTION

.

The onset of the liberation war in Donbass from the West-backed Kiev regime was the other. This war truly delineated the stakes for the existence of the Russian World. The latter is not an ethnic, but a civilizational concept that encompasses shared culture, history, and language in the Eurasian space within a traditionalist framework. To a certain extent and despitethe obvious ideological differences, the Russian Empire and the USSR embodied the same geopolitical entity.

A particularly noteworthy aspect of the ongoing crisis in Donbass is the symbolism—religious and historic—that surpasses the commonly used, but outdated Left-Right political spectrum. In the Russian context, this also means overcoming the Red-White divide of the Communist Revolution. That this war pushed Russians to examine their country’s raison d’être is somewhat remarkable: for two decades its citizens did not have an official ideology, prohibited by the Constitution that is based on Western models. The emergence of a new way of thinking in Russia will become clearer once we refer to the meaning of religious insignia, wars—Russian Civil and Great Patriotic— as well as the question of ideology in the Postmodern world.

Background to the Ukrainian Conflict

Prior to examining these factors, let us recap the recent historic events that led up to them. Since 1991, NATO has been moving closer to Russia’s borders despite its promises otherwise at the time of the Soviet collapse. Western officialdom used project Ukraine—not without its oligarchic elites’ own volition—as project anti-Russia, based upon the negative identity of the Western Ukrainian minority. Large sums of money were invested into establishing aggressively anti-Russian cadres in the media and opinion-making in places like Kiev, where none existed before. Internally, post-Soviet Ukraine was a historically problematic entity from the onset. Indeed, it attempted to house two conflicting identities without much effort at reasonable cohesion: Russians left behind across the newly instituted border as well as eastern and central Ukrainians sharing roots with today’s Russia (historically, eastern Orthodox Novorossia and Malorossia) on the one hand, and Western Ukrainians, such as Galicians (Greek Catholics in the Austro-Hungarian Empire) seeking greater ties with Europe, on the other.

In February of 2014, these two identities came to a clash, when the country saw a West-backed coup d’état under the banner of European integration. A siren song, the latter was essentially meant to transform Ukraine into a large market for dumping European goods, economically, NATO bases, militarily, with a slew of other negative possibilities that surface whenever IMF credits are involved. The coup channeled a certain level of popular discontent with the Yanukovich government, expressed at the Maidan, to bring about the logical conclusion to project Ukraine. This was an ideologically anti-Russian state—based on the ethnic fundamentalist views of its Western minority—that ignored the wishes of eastern Ukrainian residents. Its violent inception led to another logical conclusion. When the Kiev government denied that region its basic rights of language and popular representation through federalization, and attempted to crush them by force, a liberation war in Donbass—historic Novorossia since the time of Catherine the Great—began as a response. Those that Maidan attendees called “slaves” sought to be free after all.

A year and 50,000 deaths later—if the German secret service is to be believed—this conflict remains on the lips of political analysts. The Donbass infrastructure is destroyed, 2.5 million refugees fled into Russia (including previous guest workers), Ukraine’s economy is collapsing, and half of its best farm lands had already been purchased by the oligarchs and foreign companies. There is even growing disagreement within Europe—over the questions of Ukraine and the consequent Russian sanctions—the atomization of which would benefit Washington’s ability to exert even greater influence in the region over increasingly un-sovereign states.

This civil-war scenario within the grand scheme of geopolitics was not a surprise for some. Lugansk author Gleb Bobrov, for instance, released what now seems to be a prophetic novel called Epoch of the Stillborn (Epokha Mertvorozhdennykh) in 2008 through a major publisher Yauza-EKSMO. The book described a hypothetical civil war in Ukraine. In 2014, it was republished five times for obvious reasons.

This civil-war scenario within the grand scheme of geopolitics was not a surprise for some. Lugansk author Gleb Bobrov, for instance, released what now seems to be a prophetic novel called Epoch of the Stillborn (Epokha Mertvorozhdennykh) in 2008 through a major publisher Yauza-EKSMO. The book described a hypothetical civil war in Ukraine. In 2014, it was republished five times for obvious reasons.

Symbols of Tradition…and Beyond

The iconography of the liberation struggle in Donbass fuses various layers of shared Russian-Ukrainian history. It attempts to overcome its conflicting points and give birth to a new synthesis of the Russian World that surpasses the specificity of Enlightenment-based ideologies, channeling older traditions or finding positive focal points.

One prominent aspect of Donbass resistance is the usage of religious insignia. Post-Maidan protests in eastern Ukraine—before Kiev initiated an “anti-terrorist operation” against civilians in the region—frequently used eastern Orthodox images at the barricades. These were protective icons like those of the Virgin and Tsar Nicholas. Orthodox insignia, unifying eastern Slavs, remained a significant part of the Donbass liberation war since.

Tanks head into battle featuring Mandylion banners, as do road blocks and individual commanders. Igor Strelkov explicitly had the Slavyansk volunteer-battalion flag blessed in a church and paraded it through that town in mid-2014. Perhaps, subconsciously, such acts underscore the even more ancient Indo-European roots—here, the social and political leadership of warriors and priests, which stand in stark contrast to the salesman-politician within mass democracy.

Orthodox Christianity has, of course, been the thousand-year-old religious tradition in Kievan and Muscovite Rus, the Russian Empire, and, today, both in Russia and eastern and central Ukraine. And, whereas the USSR was officially atheist, as per Marxist ideology, religion never fully left the private sphere, particularly outside urban centers; at times, it was even officially sanctioned, as was the case with Stalin in 1941. Indeed, historians have pointed out that by the 1930s, the USSR turned into a neo-traditionalist state—albeit with a Communist economy—in which socially conservative values, like pro-natalism, were reintroduced in a top-down manner.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap] significant role played by Orthodox Christianity in the Donbass conflict is also evident from the fact that over 70 churches had been deliberately damaged or destroyed in this region by the West-backed Kiev forces. Novorossia’s spokespeople stated that they had no strategic military positions nearby, and that generally nothing else was hit next to the churches. Targeting religious architecture and communal centers should not be surprising, considering that Orthodoxy provides powerful cultural links between today’s Russia and Ukraine.When it comes to the Red-White schism, the official reading of history in the Soviet Union denounced many aspects of late imperial Russia on an ideological basis. In the 1990s, the pendulum swung far in the opposite direction—this time the target was the entire Soviet period—with more balanced views of history emerging in the next decade. These views are socially unifying rather than divisive, with the latter often exploited by certain outside forces looking to destabilize Russia. Whereas some polarization remains, most Russians have grown to surpass ideology and interpret the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union as the variations of the same geopolitical entity. Furthermore, many families contain these seeming contradictions within: while some of their ancestors were well-positioned during the imperial era, or were purged in the 1930s, others were farmers, laborers, and soldiers in the Red Army.

For this reason, the participants of the Armed Forces of Novorossia exhibit a variety of symbolism, the synthesis of which indicates the emergence of a balanced view of one’s past: in it, no single period is wholly positive or negative. For instance, in the spring and summer of 2014, the media paid much attention to Igor Strelkov’s interest in historic reenactment, primarily focused on the Russian Army in the First World War and the White Movement during the 1917-21 Civil War.

Donetsk’s current leader, Alexander Zakharchenko, was elected in November of 2014, choosing to be inaugurated to the sounds of the Petrine-era Russian imperial March of the Preobrazhenskii Regiment.

[dropcap]Z[/dropcap]akharchenko’s inauguration also involved Cossack participation. Prior to the artificial political division into southern Russia and eastern Ukraine, this region housed the same peoples (narod), including the Don Cossacks—a soslovie (estate) that was autonomous, but fiercely loyal to God and, often, the tsar. Dormant during the Soviet period, Cossack traditions are reemerging. They, too, came to play a prominent role at the front lines of Donbass liberation.

Cossack heritage underscores the historic complexity of Donbass. A hundred years ago, the Russian Civil War polarized the population in this region primarily on the basis of ideology between the White Movement and the Bolsheviks. Indeed, the current civil-war aspect of Donbass liberation generates this comparison. After all, many of the soldiers drafted by Kiev are actually ethnic Russians from cities like Dnepropetrovsk fighting against other ethnic Russians further east.

Furthermore, despite imperial Russian symbolism, Novorossia’s leadership explicitly sees itself as the heirs of the short-lived and transitional Donetsk-Krivoi Rog Soviet Republic (1918). And, in an industry-heavy area, primarily focused on coal mining, class-based Soviet references cannot be avoided. Novorossia’s banner is based on St. Andrew’s cross and reads, “Will and Labor”; Donetsk Republic flag, too, uses a color scheme borrowed from that period.

However, the issue of labor has more continuity between these two seemingly polar Red-White camps than one would think. Whereas the Soviet Union attempted to institute social equality in a top-down manner, some industrialists in the late Russian Empire were pious Orthodox Christians, who believed in providing charity on a personal level. They created good working conditions for their employees prior to any labor legislation, including kindergartens and women’s hospitals in the case of Abrikosov & Sons, or schools and pensions in the case of Einem, to name some.

World War Two All Over Again?

Yet it is the Second World War that maintains the greatest Soviet legacy and—the central role in the Donbass conflict. The English-language mainstream media narrative, even including the initially rare sympathetic pieces, describes Donbass residents being duped by Russian television into thinking that they are reliving the Second World War by fighting fascism. Considering that many of them are miners by profession, the derogatory implication is that these working-class people are too uneducated to know better or to think for themselves. There are two issues of note here: one of the Second World War, in general, and the other—of ideology, specifically.

First, just about every family in the former Soviet Union was touched by what in Russia is referred to as the Great Patriotic War (1941-45) with the total loss estimated at approximately 26 million. (As if the entire population of Texas and California during WW2 had been wiped out in the war.—Eds.) People are aware of their parents’ and grandparents’ experiences, some of whom are still alive. On an ideological level, this war was the great solidifier for the USSR following the turbulent years of Lenin’s Revolution and Stalin’s consolidation (1917-41). But it is far more than that. The entire geography and topography of Novorossia replicates well-known battles of the Red Army in this region, making it difficult to avoid comparisons.

The town of Slavyanoserbsk outside of Lugansk, for instance, was named after the Serbian officers at the service of Russia’s Empress Elizabeth in mid-18th century. The town was under Nazi occupation in 1942-43—with Soviet partisans active in the area—until the Red Army’s liberation in September of that year. Representatives of the Armed Forces of Novorossia emphasized how the geographic positioning between the Soviet and Nazi troops mimicked that of their own and Kiev forces. To top that off, Serbian volunteers are rumored to have liberated the town from their opponents in August of 2014.

Saur Mogila (Grave), a strategic height in Donetsk region, served as the location for one of the most fierce battles of the Great Patriotic War, with the Soviet troops recapturing it in August of 1943. This level of intensity seemed like a déjà vu in the summer of 2014, when Saur Mogila went back and forth between the Kiev troops and Armed Forces of Novorossia. The latter ultimately recaptured it in August of that year. In fact, the 1963 memorial obelisk to the Great Patriotic War was destroyed as a result of this battle.

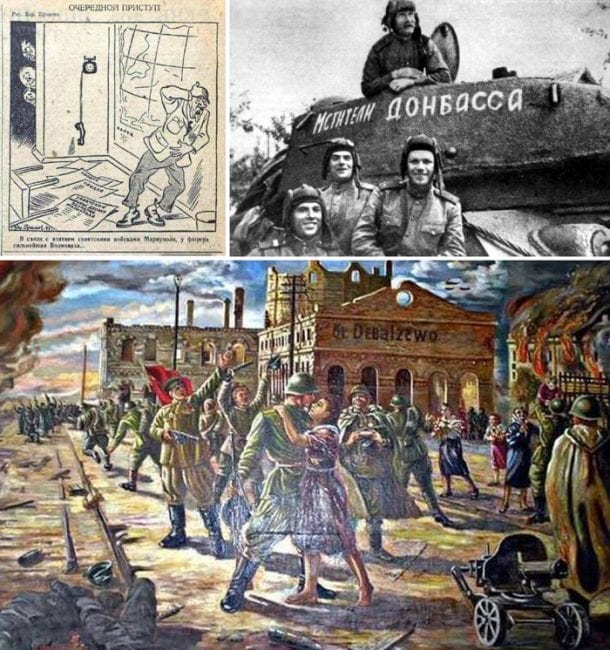

Thus, it seems that every inch of this landscape could tell a similar story. There is a caricature of Hitler “worrying” (play on words with nearby Volnovakha) about Soviet retaking of Mariupol, a 1945 photograph of a T-34 tank labeled “Donbass avengers”—including two brothers and a cousin, and an early postwar painting of the train station in Debaltsevo by a local school teacher.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]here even are numerous museum T-34s that were resurrected by the resistance fighters, like this Lugansk-area tank early in 2015.

Furthermore, there are international brigades on both sides of the conflict, apparently mimicking the Spanish Civil War of the same period. Kiev’s troops have Swedes, Spaniards, Americans. The Armed Forces of Novorossia also include Spaniards, Brazilians, Frenchmen, Serbs. If anything, the miners of Donbass could be blamed for knowing their homeland’s history too well, in drawing these Second World War-era comparisons.

Then there is the question of fascism in Ukraine that the Western media avoids, while the Russian counterpart emphasizes.

.

During the Second World War, some in Ukraine initially welcomed the Nazis over the Soviet Communists, but quickly grew to despise their colonization. Ukraine experienced varying degrees of collaboration, from the Galician SS to the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) that despised and fought everyone—Germans, Poles, Russians, and Jews—and was complicit in ethnic cleansing in Volyn region.

Donbass fighter showing Nazi-emblemed helmet belonging to one of the neonazi battalions sent by Kiev to punish the rebels.

Current Ukrainian fundamentalist ethno-nationalists, the Right Sector, the Social National Assembly, and the Azov Battalion, see themselves as the heirs of UPA’s leaders, Bandera and Shukhevich, and explicitly subscribe to the “third way,” including Second World War-inspired insignia. And it is their reading of history that was effectively established after the coup in February of 2014. That these are not simply marginal figures is evident from the complete negation of federalization and Russian-language rights to President Poroshenko calling Odessa a “Bandera city”—particularly insulting to many residents of this Soviet-era Hero City and the site of the Trade Union House massacre in May of 2014 at the hands of Maidan activists.

Don’t Throw Ideology out with Bath Water

Yet however tempting it is to think that history repeats itself, it is important to note the vast ideological differences. As some theorists pointed out, on a philosophical level the Second World War comprised the battle of three ideologies in order to determine which one best represents Modernity on a global scale. As a result, Communism (USSR) and Liberalism (U.S.) triumphed over Fascism. Subsequently, the Cold War served as the confrontation of the two remaining Modern ideologies, in which the collapse of the USSR (1991) signaled the victory of Liberalism. With Liberalism as the sole remaining representation of Modernity in the historical process—rendering the accepted 20th-century Left-Right paradigm obsolete—the period of Postmodernity commenced. Some analysts call this ideology “neo-Liberalism,” others—“post-Liberalism.” Both, however, describe the same historic trajectory, in which this set of ideas developed into its current form: the individual—with all his traditional ties removed—at the center of history, financial capital with its faceless transnational corporations as well as mindless consumerism and infotainment for the masses, the false belief in infinite economic progress (and expansion), and the secular religion of “human rights” as a tool of foreign policy that is often less than humanitarian, to name a few characteristics.

Of course, the other 20th-century ideologies did not disappear completely. But it is post-Liberalism with its global hegemony that allows them to exist and serve its own purposes. And it is the purveyors of this ideology, the elites in the official West, that sanction the existence of the self-described fascists in Ukraine, much as they do the so-called “moderate” rebels in the Middle East. Thus, the elites’ mouthpiece, mass media, whitewashes the former as “nationalists,” the “far right,” or simply “controversial.” In contrast, those that challenge its dominance ideologically, even in the most modest manner, undergo reductio ad Hitlerum. This is the case with any political party, for instance, Front National, exhibiting a semblance of traditionalism (anti-globalism), as modest as asserting national sovereignty over supra-national bodies, like NATO.

In fact, post-Liberal ideology is one of the factors that blinds many Westerners to the realities of the liberation war in Donbass. The current Western model of citizenship is an abstract one: it centers around a set of principles in which individuals are interchangeable—as long as they adopt “European values” or the “American way of life”—instead of the more traditional notions of rootedness in the landscape, cultural and linguistic ties, and ancestral bonds. Thus, those who subscribe to this abstraction have difficulty understanding how belonging to the same people (narod) overrides living in two different states—contemporary Russia and Ukraine—haphazardly formed at the time of the Soviet collapse, and why they seem so attached to their language, culture, religion, history, and land that they are willing to die for them. But even for those Russians that lean toward more traditionalist thought, it took this war—the war that was meant to separate—to ideologically and spiritually unite them with others like them across the border, to begin questioning who they really are, uncertain, but hopeful, forging the idea of the Russian World. Beyond Left and Right, Beyond Red and White.

* Originally published here.

[printfriendly]