APPRECIATION FOR THE POET

BY GAITHER STEWART

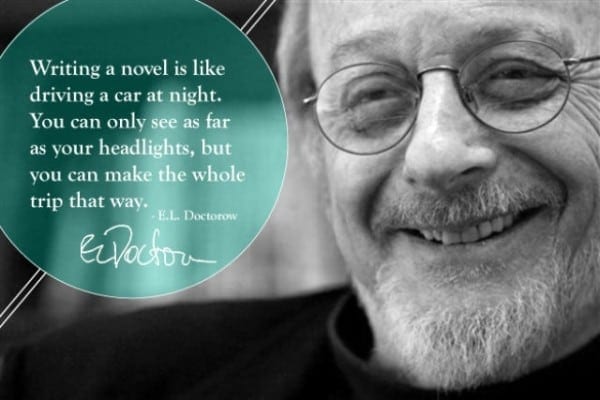

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]y most beloved poet, the American novelist with the Slavic name, E.L. Doctorow, a third generation Russian Jew, is gone. Edgar Lawrence (named after Edgar Allen Poe), was born in the Bronx in New York City just as he was supposed to. That inveterate heavy smoker Doctorow died of lung cancer at the age of 84 in Manhattan as I imagine he was destined to. In my estimation he was much too young, considering what he might have yet created in his remarkable style which if I could choose I would wholeheartedly emulate.

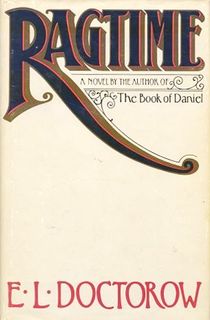

Although Doctorow was most well known for his novels Ragtime and Billy Bathgate, of the twelve he published and as much as I loved those two stories, I was struck by his use of real history mixed with creations of his imagination in his 1971 novel—as he was wont to in much of his work—The Book of Daniel, which was a fictionalized version of the arrest, conviction and execution of the Rosenbergs for allegedly passing vital atomic secrets to the Soviet Union. Like many of his novels, Daniel became a film directed by Sidney Lumet

In my mind Doctorow was a born Communist. Based on his books, I believe he considered himself a Communist which despite his legitimate (considered such by US liberals) activities as editor and professor, he hardly disguised his real identity in his literary production. Especially in this novel he expressed explicitly his undying hate for liberals.

This paragraph on the second page of The Book of Daniel, one of his first major works, shows his hate for the liberal establishment with which he mingled and lived his life while apparently maintaining his dignity, that quality today denigrated and its meaning distorted. He pronounced his hate in their faces and they facetiously ( as is their nature) praised him for it.

He (his father) didn’t like my marrying Phyllis, neither did my mother, but of course they wouldn’t say anything. Enlightened liberals are like that. Phyllis, a freshman drop-out, has nothing for them. Liberals are like that too. They confuse character with education. They don’t believe we’ll live to be beautiful old people with strength in one another. Perhaps they sniff the strong erotic content of my marriage and find it distasteful. Phyllis is the kind of awkward girl with heavy thighs and heavy tits and slim lovely face whose ancestral mothers must have been born in harems. The kind of unathletic helpless breeder to appeal to caliphs. The kind of sand dune that was made to be kicked around. Perhaps they are afraid I kick here around.

Although he was not Stephen King or Robert Ludlum, Doctorow was obviously widely read by the same liberal establishment he hated but on whose self-flagellation he thrived as a successful mainstream writer. Why? I suppose chiefly because he told good stories.

But on another level, a more psychological level, it is conceivable that liberals somehow are themselves both fascinated and satisfied by their inculcated or inherent minimum demands on society … and fuck the rest. Liberal masochism. Liberals’ see-how-we are-better-than-them phobias.

My second why? is directed at liberal-hating leftists. Why are we wary of the best of them? Of liberals? Of those who campaign and carry placards and organize sit-ins for social changes and sing inspirational songs? Of the ones who paint the rosiest of pictures of “change is possible”. Why?

E.L. Doctorow seemed to comprehend the answer. Do we?

Based in Rome, GAITHER STEWART serves as European correspondent for The Greanville Post and Cyrano’s Journal Today. As a senior editor for TGP he is also frequently involved in setting topical directions for the publication. His latest novel, Time of Exile, third volume of his Europe Trilogy, has just been published by Punto Press.

![]()

E. L. Doctorow, 1931-2015: A novelist who tackled American history

By Sandy English

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n July 21 the prominent American writer E. L. Doctorow died at the age of 84, from lung cancer. Doctorow belonged to the same postwar generation as fellow authors John Updike and Philip Roth. Even if not possessed of the most inspired artistic gifts, he represented something honest and principled in American literature. By all public accounts, he also seems to have been a thoroughly decent person.

Doctorow wrote a dozen novels, including The Book of Daniel (1971), Ragtime (1975), World’s Fair (1985), Billy Bathgate (1989) and The March (2005). He also authored a play, Drinks before Dinner, and three books of short fiction, and he published hundreds of articles and essays on literature and on political issues from a left-liberal standpoint.

Edgar Lawrence Doctorow was born in 1931 in the Bronx, the child of first-generation Americans of Russian-Jewish ancestry. (He was named after Edgar Allan Poe, a favorite writer of his father’s, who spent the last several years of his unhappy life, 1846-49, in a cottage in the Bronx).

Doctorow came of age at a time when a socialist milieu was very much part of life in New York City, particularly among Jewish workers and intellectuals. In 1948 the Stalinist-influenced American Labor Party elected a Congressman from the Bronx, its second from New York City.

The future writer was a voracious reader as a child. He remarked later in life how influenced he had been as well by New York City’s theaters, museums and concert halls, and the city’s cultural climate as a whole: “As I grew up I was a beneficiary of the incredible energies of European émigrés in every field—all those great minds hounded out of Europe by Hitler.”

Doctorow attended the Bronx High School of Science, where he began to write, and then Kenyon College in Ohio, where he was a student of the conservative Southern poet and founder of the New Criticism school of literary criticism, John Crowe Ransom.

In 1960 Doctorow published his first novel, Welcome to Hard Times, set in a small settlement in the Dakota Territory in the late 19th century. A sociopath comes into town and commits terrible crimes, leaving the place in smoking ruins. The survivors have to make the effort to rebuild before the marauder returns. An “anti-Western,” the novel, which presumably alludes not only to the lawless American frontier, but to traumatic world events of the mid-century, takes a relatively dim view of humanity. Critic Douglas Fowler points to the book’s “pessimistic” argument in favor of “the human instinct toward violence and revenge.”

His first major critical success came with The Book of Daniel, centered on a fictionalized account of the trial and execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in 1953 for allegedly passing information about the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union. That horrifying event must have had a powerful impact on Doctorow as a 22-year-old.

His novel takes place during the student protests of the late 1960s. Its central character, Daniel, the son of the Isaacsons (characters based on the Rosenbergs) gives vent to the anger and political confusion of the time. He is drawn alternately to “revolutionary” gestures and to attempts at a more sober consideration of the first half of the 20th century, which never proceeds very far. Daniel’s sister meanwhile makes an attempt to end her life. Toward the end of the book Doctorow includes a harrowing description of execution by the electric chair.

The novelist told an interviewer that once he started The Book of Daniel he discovered he “could hang an awful lot on it—not only the explicit and particular story of two people…but also the story of the American left in general and the generally sacrificial role it has played in our history.” The writer explained, “Certainly in the history of this country, the radical is often sacrificed and his ideas are picked up after he himself has been destroyed.”

Doctorow suggested that he had been “fully sensitive to the McCarthy period generally,” but that the Rosenberg story “didn’t propose itself to me as a subject for a novel until we were all going through Vietnam.” Ragtimebrought Doctorow widespread recognition and, one might add, respect and affection, which is not something one could say about very many of his contemporaries. It his perhaps his greatest achievement, despite some of its storyline extravagances and implausibilities. The novel is set in the first years of the 20th century and employs both fictional characters as well as significant historical figures such as magnates J. P. Morgan and Henry Ford, the anarchist Emma Goldman and black educator and author Booker T. Washington.

The novel in its best sections leaves a genuine imprint on the reader’s imagination. For example, when one of the central characters, the Eastern European immigrant Tateh, goes to Lawrence, Massachusetts seeking work, he ends up involved in the great textile strike of 1912, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). After the strike leaders have been arrested,Ragtime describes the arrival of the new IWW leader, William “Big Bill” Haywood:

“He was a Westerner and wore a stetson which he removed and waved. A cheer went up. Haywood raised his hands for quiet. He spoke. His voice was magnificent. There is no foreigner here except the capitalists, he said. The place went wild.”

At the time Doctorow’s novel was criticized for the liberties the author took with historical facts. While he may play a bit fast and loose with certain details—the influence of new and increasingly fashionable postmodern trends is perhaps already at work here—the general thrust of Ragtime is an attempt to get at more important truths about the past, including the ones excluded in the official narrative of American history.

What is weaker about Ragtime is the unworked-through and sometimes ahistorical approach to the early years of the 20th century. For example, another lead character in the work, the African-American musician Coalhouse Walker (inspired by the protagonist of Heinrich von Kleist’s 1811 novella Michael Kohlhaas), somewhat improbably forms an organization of black workers to terrorize racists—with the active sympathy of some whites—and ultimately seizes Morgan’s mansion, where he is assassinated. The tone of these scenes seems contrived and stage-managed.

World’s Fair (1985) was Doctorow’s most autobiographical piece, and recreates the world of New York City, again during the Depression era. It is narrated by a boy named Edgar and centers on the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows, Queens. World’s Fair unquestionably succeeds in evoking the period. It brings to mind a different type of memoir, Alfred Kazin’s A Walker in the City, set in Brooklyn in the 1920s.

Billy Bathgate won the National Book Critics Circle Award and a PEN/Faulkner Award. It concerns a teenager, Billy Bathgate, who becomes an apprentice to Jewish-American mobster Dutch Schultz in 1932. Billy narrates and, although he makes keen observations about the nature of the gangster business, there is little sense of the world beyond this lowlife existence, one in which an economic depression is taking place. Nor is Billy overly shocked by Schultz’s killings and cruelty, even though they appear designed to affect the reader. Billy never seems transformed by his own experiences, let alone the conditions of his era. The author seems to be suggesting that homicidal violence is intrinsic to the national character, a view that is both lazy and untrue.

Dustin Hoffman and Nicole Kidman in Billy Bathgate (1991)

He then turned his attention to one of the most titanic events in American history, the Civil War. The March, which won another PEN/Faulkner Award as well as the National Book Award, follows the Union army of General William Tecumseh Sherman in his “march to the sea” through the South in late 1864 and early 1865. Its characters are freed slaves, Union and Confederate soldiers, doctors in the Union army and Southern civilians. Doctorow recreates the blood, hunger and death, the pillage carried out by the Union army and the virtual destruction of the South.

Fellow writer John Updike noted in a review in the New Yorker: “Sherman’s march is conjured up as a human entity as large as the weather, a ‘floating world’ that destroys as it goes and carries along some living fragments. It is a revolution in motion—‘On the march is the new way to live.. .. The world was remade, everything become something else.’”

The novel was written during some of the bloodiest days of the American invasion and occupation of Iraq. It is unquestionably Doctorow’s commentary on the Iraq War and on the evolution and possibilities of the United States as a society. Reading the work, one senses that Doctorow felt obliged to find an episode of justice and progress in American history, portrayed realistically in the midst of an event as violent and ruthless as Sherman’s march.

One senses as well that these are the aims of someone who does not believe that genuine historical progress is still in operation in the 21st century. It would seem that, for all of his attention to history, Doctorow, like many other artists of his generation, was unable to make sense of the great events of the first half of the 20th century, particularly the Russian Revolution, Stalinism, the causes of two world wars.

The Cold War and the McCarthyite onslaught on socialist thought no doubt had a chilling effect on him, creating a certain defensiveness and lack of political confidence in a left-wing perspective that never entirely went away. The eventual collapse of the USSR (which he referred to as the end of a totalitarian dictatorship) strengthened the view that no alternative to capitalism was possible. Doctorow’s art took on the character of a moral stance against all odds, but not one imbued with much hope for the future.

One feels that something is missing in many of his works. There is considerable technical expertise and command of structure and story, but no single novel is entirely satisfying or breathtakingly illuminating. Ragtime ends on a note of unlikely radical terror, Billy Bathgate fails to examine convincingly the connection between the 1930s and the world 60 years later, and The March leaves us wondering why Doctorow has raised the topic of the destruction of the South in the context of the eruption of American imperialism.

Several of Doctorow’s novels were turned into films: Henry Fonda and Janice Rule starred in Welcome to Hard Times (1967, directed by Burt Kennedy) and in 1983 director Sydney Lumet made a film version of The Book of Daniel, simply entitled Daniel, featuring Timothy Hutton. Ragtime (Milos Forman) was adapted for the screen in 1981 and a Broadway version appeared in 1988, winning four Tony Awards. A version of Billy Bathgate (Robert Benton) was released in 1991 starring Dustin Hoffman as Dutch Schultz.

Doctorow was legitimately critical of contemporary literature. In a 1990 interview with Bill Moyers, he commented, “I don’t believe we’re doing work equivalent to our nineteenth-century or even to some of our early twentieth-century novelists. …We have given up the realm of public discourse and the political and social novel to an extent that we may not have realized. We tend to be miniaturists more than we used to be…I think it’s true that we’ve constricted our field of vision. We have come into the house, closed the door, and pulled the shade.”

Doctorow was a defender of Constitutional rights, an opponent of censorship and a prominent critic of the Iraq War. In one of his last pieces of political commentary in April 2012, published in the New York Times, he identified state surveillance, the use of torture and mass incarceration as among those features of life that were rendering “the United States indistinguishable from the impoverished, traditionally undemocratic, brutal or catatonic countries of the world.” tribute

Sandy English is a political writer and cultural analyst for wsws.org.

![]()

FACT TO REMEMBER:

IF THE WESTERN MEDIA HAD ITS PRIORITIES IN ORDER AND ACTUALLY INFORMED, EDUCATED AND UPLIFTED THE MASSES INSTEAD OF SHILLING FOR A GLOBAL EMPIRE OF ENDLESS WARS, OUTRAGEOUS ECONOMIC INEQUALITY, AND DEEPENING DEVASTATION OF NATURE AND THE ANIMAL WORLD, HORRORS LIKE THESE WOULD HAVE BEEN ELIMINATED MANY YEARS, PERHAPS DECADES AGO. EVERY SINGLE DAY SOCIAL BACKWARDNESS COLLECTS ITS OWN INNUMERABLE VICTIMS.

![]()

REBLOGGERS NEEDED. APPLY HERE!

Get back at the lying, criminal mainstream media and its masters by reposting the truth about world events. If you like what you read on The Greanville Post help us extend its circulation by reposting this or any other article on a Facebook page or group page you belong to. Send a mail to Margo Stiles, letting her know what pages or sites you intend to cover. We MUST rely on each other to get the word out!

And remember: All captions and pullquotes are furnished by the editors, NOT the author(s).