Tragedy & Farce: Reconsidering Marxian Superstructural Analysis of Heterodox Social Movements

Tragedy & Farce: Reconsidering Marxian Superstructural Analysis of Heterodox Social Movements

Part I: Utopia vs. Myth, the Poetry of the Past, and Social Revolution – a general introduction to this series

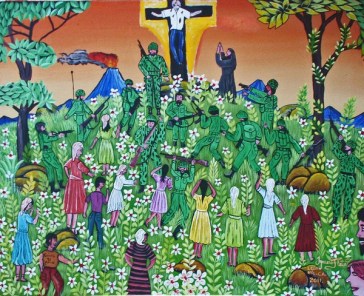

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]et us begin by resolving that there were three socio-political ideologies of modernity – liberalism, communism, and fascism; the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd political theories, respectively. New developments in the global arrangement of socio-economic, ideological, and geopolitical forces in recent years force us to examine these with fresh eyes. On the one hand, we need to recognize the common philosophical heritage of all of these three ideologies in modernity, and thereby reveal the instances in which they consciously or unconsciously collude, while on the other hand delineating between their respective understandings of their roles as ideologies. In particular, the aim of this series is to reconcile the Marxian analytical framework with the base and super-structural features of new and syncretic socio-political movements, in their purely aesthetic form, as well as in their deeper ideological aspects.By J. Arnoldski and Joaquin Flores![]()

The starting point of our investigation is the recognition that we live in a highly ideological time, and yet it appears to many that we do not. That many in the West believe we live in a ‘post-ideological’ period is in fact a testament to the total saturation of liberal ideology. Since the victory of the liberal West over the Soviet Union and the proclamation of the liberal “end of history” (in the words of F. Fukuyama), liberalism has become so tightly woven into every facet of life to the point that it is indistinguishable from every-day life itself. As such has proven to be the most effective totalitarian ideology hitherto created by mankind.

‘

Liberalism & Marxism

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]iberalism appeals to our innate individual instincts, but does so in such a way as to make a war upon our equally innate collective instincts. Both of these innate instincts – the individual and the collective – are integral parts of the human experience. A foremost instance of the harsh atomization imposed by liberalism can be seen in the fact that sex seems to be a particular focus of contemporary liberal ideology, pushed forward in standard form as a wedge issue between progressive liberal and conservative liberal media-political groups.[1] To formulate a comprehensive critique of liberalism as the ideology of capitalism means to re-examine how we understand radical anti-capitalist movements today. This means, first and foremost, endeavoring to reconsider and distinguish the base and superstructure in Marxian theories about heterodox (and apparently non-leftist) social movements. On this basis we can proceed with a renewed understanding with which to analyze and then transcend (in theory) particularly divisive wedge issues.These divisive issues are indeed not fundamental per se, but rather are super-structural issues which mainly exist in the realm of discursive traps; the types and forms of language used which direct us to associate these with other distinct realms of thought and activity. These are modes and realms which hitherto are considered by Marxists to be hostile to the historical and material class interests of the proletariat; they have been associated with the politics of reaction, pre-modernity, and/or the bourgeois or petit-bourgeois class forces in a mode of crisis. Other issues are ethnic, gender and sex, which divide proletarian class forces. The ossification of a politically correct neo-liberal ‘globalist’ culture surrounding these can justify “human rights imperialism”: these represent crucial examples of the permutation of otherwise “anti-liberal” theories ( they are not formally open for debate) by the liberal paradigm of modernity itself.

The utopian elements in liberalism found expression in its branch of ‘progressivism’, and the Marxists like the utopian socialists before them, found a common ground with liberals. The futurist strain of Fascism, also appealed to this progressivism, and radical republicans, anarchists, syndicalists, as well a red republicans in Italy were among the founders of this 3rd political theory on the Italian plane. The progressivist framework, which allowed for and engendered cross-semination between the three political theories, situates them all as modern political theories. However, the kernel for future political theories exists in the second and third – both of these pose the question of what will follow the modern, i.e capitalist (liberal) order.

Thus, there is an inherent error in thinking of the three ideologies of modernity in static form; of thinking of them as structures which stand alone. It is then erroneous to contrast these with ‘syncretic’ ideologies, or to consider the third political theory as distinctly syncretic as opposed to the first and second. All three political theories of modernity influenced each other; each was created out of ideas not only of those which preceded it, but concretely emerged from the real-existing material world and everything inherited from it. Each political theory did not emerge in complete form, and so for example liberalism today has features within it of both communism (i.e Marxism) and fascism. Likewise, Marxism was born not only out of Liberalism and its contemplation of Feudalism and pre-modernity, but was simultaneously interacting with; subsuming here and rejecting there, the ideas from radical-liberalism, nationalism, existentialism, and anarchism that are, not just incidentally, all together the foundations of fascism.

‘

A key given by Marx: The Eighteenth Brumaire

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]o many who understand the trajectory of historical development through a Marxian lens, few things seem more at odds with Marx’s own views this than his “correction” of Hegel in the opening lines of The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. The essay in itself remains one of Marx’s best descriptions of his theory of the capitalist state. The analysis of the Marxians is intellectually honest when it operates with an understanding of the objective and subjective conditions in which historic transformation is effected, according to the analytical framework of historical or dialectical materialism. Moreover, it exhibits a distinct fidelity to the proposed science when it looks objectively and without emotive prejudice at the super-structural forms which said historic transformations take on.The identifiable problem then, when applying the same Marxian analysis to the present, that is, when it relies on short-hand super-structural cues and gives into the pressure of activist culture, it may fail particularly when looking at contemporary, i.e. early 21st century social movements in the post-modern era. A key to understanding this problematic area, as a suitable introduction to our inquiry, may lie in a revised reading of the first chapter of Eighteenth Brumaire.

Thus it will be important for us to examine not only how this correction is misinterpreted by Marxists, but perhaps also where Marx himself might be corrected – or better perhaps, brought into alignment with his own proposed science. This will raise the question of what this means in the context of the super-structural realm of aesthetics, culture, words (or discursive traps), ideas, and symbols. If Marx appears to contradict himself, it may be important to turn him right-side up.

The confusion of form for substance not only a theoretical problem, but one which has an extraordinary impact upon the present: if radical socialists, anarchists and communists today are relying on super-structural cues to determine the identity of their ‘class opponents’, this may be a tragic misdirection, and in hindsight, a farce. As we begin to suffer from the ‘information overload’ of the internet age, and where attention deficits run at an all time high, it is in fact difficult not be economical when looking for certain cues: communists wave red flags, anarchists black ones, while socialists mimic liberalism by refraining from overt symbolism. Instead the socialists use ‘liberal’ and ‘progressive’ language and syntax to reach out to anyone to the left of the center. All three, however, at best ignore and at worst vilify those on the center-right and beyond.

‘

Marx vs. The Marxists: Total subsumption of all classes into a proletariat

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he problem with the marginalization or vilification of people on ‘the center-right and beyond’ is of course that in terms of electoral processes, it is indeed improbable to succeed in this terrain without ‘center-right and beyond’ ideas appealing to members of the proletariat. It is too simple to sweep these under the rug of ‘false consciousness’ without seriously calling into question the potential for (and reality of) class agency in general. In connection with this is a problem in the way that contemporary communist etc. groups have ignored actual Marxist theory and simplified their definition of ‘proletarian’.Rather, not only in looking at civil society, but also in Marxist theory, we should understand that under conditions of late-capitalism, i.e. late modernity, that capitalist development has proletarianized all other classes (petit-bourgeois, etc.) through various ways. All prior classes, which exist today in proletarian form, have been subsumed by capital and proletarianized; all are involved in the critical valorization process. By definition therefore all are involved in the production of surplus value. All labors are in the final analysis geared towards capital accumulation; and all are in the final analysis alienated from the laborer and accumulated by the capitalist, through the cycle of production, from the products of said labor.

The mechanisms of capital accumulation, in the context of late-capitalism, are not only the appropriation of surplus value in the form of wages in the typical employer-employee relationship; but rather all relations of production or social relations are geared towards capital accumulation by the finance capitalists. Pre-capitalist (rents, taxes, feudal), capitalist (wages), and late-capitalist (financial/speculative/lending) modes of capital appropriation, are all used in late-capitalism as methods of capital accumulation.

Thus, classes which appear as managerial, petit-bourgeois, lumpen, administrative, etc. have been proletarianized. Thus their struggles, when directed at the established order, regardless of the poetry, (slogans, symbolism, battle-cries, imagery, and banners), are generally proletarian in substance even if not in apparent form.

So in regarding interpretive short-cuts, as useful as they are, these have severe limitations because they refer to largely outdated interpretations of aesthetic and other super-structural cues. This is especially the case as various social movements arising in opposition to capitalism stem from a seemingly chaotic or discordant mix of assorted radicalisms. These even include those which look and feel as though they originate from the fascist far-right, and may in fact originate in this. As we will explore in this series, these are often objectively anti-capitalist and proletarian movements which are wrapped in the aesthetics and historical references of fascism and various neo-fascisms in Europe, and in the US often take the form of constitutionalism and libertarianism as well.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]f indeed these ‘far-right’ radicalized groups were in fact doing the work of the ruling class, mobilizing to crush initiatives of worker’s power in the name of the state, the church, and in the class interest of the petty-bourgeoisie (and the traditional forces of reaction in general), then the 20th century Marxist classification of these groups as ‘fascist’ may indeed be apt: our ‘short cuts’ would have served us right.Indeed and likewise it would also be a tragedy if ‘left-wing’ fighting groups such as Antifa were in fact attacking other proletarian movements opposed to capitalism, which only happened to appear as reactionary petty-bourgeois permutations of class power.

At the same time we cannot directly define counter-mobilization against communist groups by ‘far-right’ groups as counter-mobilizations against the working class as a class. Objectively, these are relatively small fights between distinct ideological groups among the working class (i.e, left vs. right), and mimic the fights between religious sects, and do not represent the interests of one class against another class. ‘Communist’ vs. ‘Fascist’ self-references and symbolism are notional abstractions and by and large do not materially connect to proletarian vs. petit-bourgeois class forces, respectively, even though they refer to these abstractly, i.e, in the world of ideas.

Certainly, ‘divide and conquer’ has been an effective tactic for the ruling class to maintain class rule. This may extend far beyond what was previously understood. It brings into question how we understand and interpret the supposed offspring of various 20th century social movements.

The capitalist state and its overly armed apparatus of state power, its meandering bureaucracy and bountiful resources, stands as a seemingly unconquerable behemoth. Revolutionary Marxist groups apparently pale in comparison in terms of their capacity to project power. Significantly less powerful are the above mentioned non-Marxist anti-capitalist movements and groups, many not even identifying with the left, and most of these taking a decisively anti-communist perspective in terms of nominal ideology. These groups make excellent surrogate targets for revolutionary Marxist and Anarchist groups; it is possible to strike against them in the streets and in virtual spaces. Victories here serve to satisfy the need to have victories, but may indeed work against the real aims of the struggle against capitalism.

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]yncretic social movements in Eurasia are already overcoming the problem we are looking at, and therefore some of these examples will be discussed in this series. Other examples include Pan-Arab and Pan-Syrian Socialism (such as Ba’athism or the SSNP), as well as revolutionary nationalisms in Latin America, Liberation Theology, revolutionary groups in the Novorossiya parts of former Ukraine, and others. They have influenced our opinions as well, but more concretely show what solutions can be drawn and moreover are more than ‘proof of concept’ that such endeavors can be undertaken with a high degree of efficacy.Returning to Marx in The Eighteenth Brumaire

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]arx writes:“Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce [….]And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language. Thus Luther put on the mask of the Apostle Paul, the Revolution of 1789-1814 draped itself alternately in the guise of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and the Revolution of 1848 knew nothing better to do than to parody, now 1789, now the revolutionary tradition of 1793-95. In like manner, the beginner who has learned a new language always translates it back into his mother tongue, but he assimilates the spirit of the new language and expresses himself freely in it only when he moves in it without recalling the old and when he forgets his native tongue.”

“When we think about this conjuring up of the dead of world history, a salient difference reveals itself. Camille Desmoulins, Danton, Robespierre, St. Just, Napoleon, the heroes as well as the parties and the masses of the old French Revolution, performed the task of their time – that of unchaining and establishing modern bourgeois society – in Roman costumes and with Roman phrases. The first one destroyed the feudal foundation and cut off the feudal heads that had grown on it. The other created inside France the only conditions under which free competition could be developed, parceled-out land properly used, and the unfettered productive power of the nation employed; and beyond the French borders it swept away feudal institutions everywhere, to provide, as far as necessary, bourgeois society in France with an appropriate up-to-date environment on the European continent. Once the new social formation was established, the antediluvian colossi disappeared and with them also the resurrected Romanism – the Brutuses, the Gracchi, the publicolas, the tribunes, the senators, and Caesar himself. Bourgeois society in its sober reality bred its own true interpreters and spokesmen in the Says, Cousins, Royer-Collards, Benjamin Constants, and Guizots; its real military leaders sat behind the office desk and the hog-headed Louis XVIII was its political chief. Entirely absorbed in the production of wealth and in peaceful competitive struggle, it no longer remembered that the ghosts of the Roman period had watched over its cradle.”

“But unheroic though bourgeois society is, it nevertheless needed heroism, sacrifice, terror, civil war, and national wars to bring it into being. And in the austere classical traditions of the Roman Republic the bourgeois gladiators found the ideals and the art forms, the self-deceptions, that they needed to conceal from themselves the bourgeois-limited content of their struggles and to keep their passion on the high plane of great historic tragedy.”[2]

On the one hand, this crucial passage is one of Marx’s most seminal works in analyzing revolutionary experience and drawing theoretical conclusions; Marx asserts that “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”[3]

As examples we see that Marx recounts the Lutheran Reformation’s harkening back to the Apostle Paul, Cromwell and the English’ appeal to the Old Testament, and the French Revolution’s Roman drapery as cases in which revolutionary transformations drew their aesthetics and presentation from the past in order to present a kind of historical legitimacy and a sense of historically redeemed struggle against the contemporary order.

‘

Hypothesis vs. Experience: Theory must reflect reality

[dropcap]Y[/dropcap]et, in stark contradiction to this prescient recognition of such an undeniable reality, Marx proceeds to suggest that the future social revolution “cannot take its poetry from the past but only from the future. It cannot begin with itself before it has stripped away all superstition about the past. The former revolutions required recollections of past world history in order to smother their own content.”[4]Why does Marx look at a proven effective use of the poetry of the past only to argue that the future social revolution can only takes its poetry from the future? Marx proposes: “The revolution of the nineteenth century must let the dead bury their dead in order to arrive at its own content.”[5]

Hence the meaning of the formula “first as tragedy, then as farce”: the appropriation of past and existing forms is a tragically imposed, circumstantial necessity, and a subsequent repetition of such represents little more than a botched, castrated, reactionary parody. Marx, despite recognizing the importance of the Apostolic guise of the Reformation or the Roman pretensions of the French Revolution, goes so far as to denounce the influence of “the tradition of dead generations” as a “nightmare on the brains of the living.”[6]

While such an appraisal made by Marx may indeed be restricted to bearing prescience in reference to the French coup of 1851, the conclusion that the “names, battle slogans, and costumes” drawn from the past in the midst of revolutionary struggle inherently constitute a reactionary, self-abortive farce is of serious, far-reaching importance. We propose that it is a mistake.

And this is a mistake, indeed a confused contradiction in Marx’s discussion of the relationship between the superstructure (the ‘poetry’) and the base (objective class and economic forces), which has either bore profoundly negative repercussions in the analyses produced by Marxists, or has actually been refuted by past and contemporary revolutionary experiences.

Not only was the ‘poetry of the past’ effective in its time, we cannot, in the final analysis, conceive of a way in which it was avoidable. It was indeed necessary. The revolution in 1917 didn’t just refer to its own utopian promise and future. It had to fortify itself in the mythology of 1871, 1848, and 1792-94. And not only that, but also the entire “history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles” (Communist Manifesto, 1848). One cannot positively judge these without valorizing them, and one cannot put value into history without mythologizing them.

Indeed it has become all too common for Marxists to summarize the the presence of ancient, Medieval, pre-modern, or even early bourgeois imagery, sympathies, or undertones as indicative of a pro-capitalist, reactionary, and counter-revolutionary nature. In reality, they are mistakenly denouncing movements which have the potential to produce genuine social change and be an important part of revolutionary transformation.

‘

Our Proposal

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]e propose to understand such movements in the Marxian sense, to the contrary, as often “revolutionary” even when draped in the robes of myth, even when donning the mask of reaction.But we ask this: why must it be the case that revolution must “let the dead bury their dead”? Has it in fact been the case, and is it likely to be the case? To this, our answer is “No”.

Are communist, anarchist, and socialist movements today approximately the same as they were 150 year ago? Are ‘ultra-right’ and fascist movements today approximately the same as they were 70 or 100 years ago? To both of these, our answer again is “No”.

These groups and movements have undergone tremendous change, a century has passed with base acting upon super-structure and super-structure acting upon base, producing an irreversible chain of phenomena in its wake. The views of Marx as expressed in 18th Brumaire have already been contradicted in fact and practice. Yet at the same time, there are elements of truth as well: there are different views of the past but people can be unified by a common idea about what sort of future would work. Still, we see this not as a reason to condemn those who use the power of myth in their agitation and identity, but rather as a reason for those who understand it to not confuse its subjective poetry for its objective function.

Just as the subjective use of symbolism and language of an ostensible communist party does not make it objectively communist in the proletarian revolutionary sense of the term (we can look at any number of euro-communist parties, for example), the poetry of fascism and myth does not make the groups and movements using them objectively fascist in the 20th century bourgeois reactionary sense of the term.

It is also important to recall this: the communist movement not only in the 20th century but even in the time of Marx also wrote its own stanzas about the past, its own poetry of the French Revolution, Grachus Babeuf, August Blanqui, the League of the Just, the Conspiracy of Equals, the Communards, and so forth. As events moved us forward in time, these stanzas become farther removed from us. Communists now refer to the past and trace its ‘modern’ origin to a time nearly two centuries ago. Can a communist movement not have a history? Can it not remember and even mythologize itself? Are red or black flags today allusions to the great year 1917 at all like the conjuring of “the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language”? We believe they are.

Looking openly at these questions will be among the tasks of this series. We invite our so-inclined readers to join us as we explore these pressing questions. This will involve a dissection of the complex relationship between base and superstructure, which is one which was also taken up by the mid-century modernists (the so-called post-modernists) and beyond.

It will require a look at culture, the evolution of youth culture and subculture, and real existing syncretic and anti-liberal socio-political movements today. These trace their origins primarily to the second-half of the 20th century.

Some of this will also require us to look at these superstructural conceptions of poetry; the poetry of the past vs. the poetry of the future. Of course, poetry about the past is not from the past, but from the present – it is only about the past. Likewise, the poetry of the future is not from the future, but from the present. And, in both cases, they refer to the present – it is for us in the present, and in the present that anything can be done. In that sense, these – past and future poetry – are both contemporary narratives.

If we accomplish our task, we will raise more questions than we answer, and hopefully provoke a better reason to develop this even further. It is a subject too vast for any single canvas, and one which we can only hope to sketch with some details for the reader.

**

NOTES

[1] Sex and sexuality, which at first strike us so very personal, are like language in that they form the connective tissue between the individual and the collective. It should not surprise us then, that liberalism today focuses so much of its ideological and intellectual work primarily in the area of sexuality and gender. Liberalism is atomizing, and induces a form of social schizophrenia in promoting a prudish social idea that we are each private and individual consumers. It is even prudish in its overt commercialization of sexuality. It produces a ‘one size fits all’ individual, under-sexed through over-sexualization, lonely in a sea of ‘too many people’; devalued and fit for consumption and production within the capitalist cycle; surrounded by abundance and yet alienated from this product of labor. Liberalism is the ideology of capitalism in that it champions these.

[2] https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/ch01.htm#2

[3] ibid

[4] ibid

[5] ibid

[6] ibid

J. Arnoldski is a student of Eastern European history and an American-born activist of Polish and Russian heritage currently based in Wroclaw, Poland. Formerly an activist in the American communist movement, he currently works as one of the founders of International Students Aid to Donbass. His expertise and interests include Russian history, with a specialization in the Soviet period, Eurasianism, and the Fourth Political Theory of Alexander Dugin. Joaquin Flores serves as Director and Chief Editor for The Center for Syncretic Studies (CSS). A onetime activist with the labor movement in the United States, he is also founding editor of Fort Russ, and a special editor and correspondent for The Greanville Post (Belgrade).

Copyright © Center for Syncretic Studies 2015 – All Rights Reserved. No part of this website may be reproduced for commercial purposes without expressed consent of the author. Contact our Press Center to inquire.

For non commercial purposes: Back-links and complete reproductions are hereby permitted with author’s name and CSS website name appearing clearly on the page where the reproduced material is published.

Quotes and snippets are permissible insofar as they do not alter the meaning of the original work, as determined by the work’s original author.

“…in the new exuberant aggressiveness of world capitalism we see what communists and their allies held at bay.” – Richard Levins (Source: The Proletarian Center)

FACT TO REMEMBER:

IF THE WESTERN MEDIA HAD ITS PRIORITIES IN ORDER AND ACTUALLY INFORMED, EDUCATED AND UPLIFTED THE MASSES INSTEAD OF SHILLING FOR A GLOBAL EMPIRE OF ENDLESS WARS, OUTRAGEOUS ECONOMIC INEQUALITY, AND DEEPENING DEVASTATION OF NATURE AND THE ANIMAL WORLD, HORRORS LIKE THESE WOULD HAVE BEEN ELIMINATED MANY YEARS, PERHAPS DECADES AGO. EVERY SINGLE DAY SOCIAL BACKWARDNESS COLLECTS ITS OWN INNUMERABLE VICTIMS.

And remember: All captions and pullquotes are furnished by the editors, NOT the author(s).