[dropcap]R[/dropcap]ecent acts of nonviolent civil disobedience have gained a significant amount of national attention. On June 27, Bree Newsome scaled a flagpole in front of the South Carolina State House to take down the Confederate flag that was on display. On July 18, Black Lives Matter protesters interrupted presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley during a speaking event in Phoenix, Arizona. Another incident began on July 29 when activists rappelled off the St. Johns Bridge in Oregon for forty hours to block a ship as it embarked for the Alaskan Arctic to begin drilling for oil and natural gas. Critics claim these actions, along with marches and rallies, are a complete waste of time.

How can climbing a flagpole or hanging from a bridge reform society or improve our political system? How can marching down the street with a cardboard sign that reads “Black Lives Matter” do anything other than disrupt traffic? Why do activists do what they do?

It begins with the idea that our actions may not have an impact on the world today, tomorrow, or anytime in the near future. What we do in the present moment, while extremely important, might not have its intended effect until decades later. Teachers, for example, provide students with knowledge and skills necessary to earn good grades during the school year, which certainly has intrinsic value, but ultimately teachers work out of faith, hoping to create good citizens for the future. The effect a teacher has on students will not be known until many years later when these students are using their skills and knowledge as adults.

This is true for activists, as well. The intended effects of their actions are often not realized until much later. In fact, it may take an entire generation before any effect is felt at all. Many abolitionists who strove to end slavery did not live to see the outcome of their work. They organized in secret, wrote publications, passed out leaflets, and helped slaves escape using the Underground Railroad long before emancipation occurred. They risked their lives, working out of faith, hoping that one day slavery would end. Likewise, massive social movements in the  1960s achieved monumental legal victories, such as the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the Clean Air Act, but full effects of desegregation, the universal right to vote, and environmental protection was not fully felt until many years later.

1960s achieved monumental legal victories, such as the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the Clean Air Act, but full effects of desegregation, the universal right to vote, and environmental protection was not fully felt until many years later.

Therefore, the actions by any one person or the success of any one rally, march, strike, or sit-in cannot be measured by short-term outcomes. They must be evaluated by the sum total of small, seemingly meaningless actions by many people over the course of many years, sometimes decades. While short-term outcomes are real and worthy, the accumulated effects of long-term achievements have far-reaching implications. They set into motion a series of events that have a ripple effect.

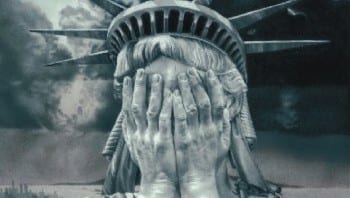

How can climbing a flagpole or hanging from a bridge reform society or improve our political system?![]()

In the moment, success can seem unlikely, if not entirely impossible. Activists require faith to envision that what they do will pay off, but sometimes not for years to come. In his book, Wages of Rebellion, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Chris Hedges writes, “Rebels share much in common with religious mystics.” Hedges has written twelve books and worked for nearly two decades as a foreign correspondent in more than fifty countries. He has interviewed activists and rebels from across the world, so he understands them well. He says, “They hold fast to a vision that often they alone can see.” Their thoughts and actions sometimes appear to be completely irrational, making very little sense to anyone but themselves. They put forth a vision for a better future, which is exactly what Martin Luther King did when he said, “I have a dream.”

Activists speak up when others are silent and they stand up when others sit down, all while understanding that what they hope to achieve might not occur. “They view rebellion as a moral imperative, even as they concede that the hope of success is slim and at times impossible,” writes Hedges. Rebels act out of faith, knowing that one day their actions could very well have an effect on the world. It is this leap of faith, and sometimes irrational hope, that drive them forward to do what they do. “There is nothing rational about rebellion,” continues Hedges. “To rebel against insurmountable odds is an act of faith, without which the rebel is doomed.” In other words, activists are moved, not by the knowledge that they will succeed, but by the feeling of hope that what they do will make the world a better place. Hedges reminds us that this is exactly what Buddhists call karma—performing good deeds and thinking positive thoughts today so the world is better tomorrow.

Activists are deeply grounded in faith, but it is not based on superstition. It is based on historical understanding that nonviolent civil disobedience categorically works to enact positive change. The empirical evidence is everywhere: gay rights, desegregation, the right to vote, women’s liberation, ending slavery and apartheid, enacting human rights, and improving the living conditions for the most vulnerable are direct outcomes of social movements. The right to vote and desegregation are the results of boycotts and lobbying efforts. Organized workers earned better working conditions, shorter working hours, and workplace safety laws by going on strike. War resisters and conscientious objectors have ended wars. These victories are not imagined; they are real and they affect the world every single day.

Historical understanding involves realizing that our family extends to everyone who has ever lived and who has yet to live. Our lives are the direct result of the actions of previous generations, and our lives today will have an effect on future generations. Civil and human rights, science and technology, everything we experience, was granted to us because of actions, ideas, innovations, and struggles of previous generations. Untold numbers of people had a vision of the world, and they worked to achieve at least some version of it. We have a duty to not only to pay homage to past struggles, but we must also carry on for future generations.

In addition to faith and historical understanding, activists have authentic experiences and unique personalities. Many of them know what it is like to be poor and to live in dangerous conditions under the threat of violence by their neighbors and the police. Many use public services, and some are completely dependent on government assistance. They witness the effects of inequality, poverty, war, and climate change first hand as teachers, nurses, social workers, volunteers, scientists, and journalists. Countless numbers have been victims of discrimination, police brutality, rape, addiction, and so on. These experiences, along with many others, inspire them to work together and to depend on others for help, giving them a strong sense of solidarity and empathy toward others in similar situations. This is exactly why they donate what money they can spare, work in nonprofits, and work to enact social change.

These experiences help shape their personalities and virtues. Hedges interviewed many activists for his book, including Julian Assange, Mumia Abu-Jamal, and Jeremy Hammond, and he describes them clearly:

Rebels . . . are men and women endowed with a peculiar obstinacy. Willing to accept deprivation and self-sacrifice, they are not overly concerned with defeat. They endure through a fierce independence and courage. Many, maybe most, have difficult and eccentric personalities. The best of them are driven by a profound empathy, even love, for the vulnerable, the persecuted, and the weak.

To be an activist also requires courage. When people follow their vision and stand up for something they believe in, they put themselves in danger. They risk being criticized by society, alienated by friends and family, and harassed and imprisoned by police. For some, it can mean deportation or death. Whether it is an extremely polarizing issue, such as abortion rights, or something less controversial, like registering voters, there will always be push back from corporations, the ruling class, or anyone whose world view or way of life is threatened by what activists do. It takes courage to challenge the status quo and to break unjust laws in the face of danger.

Is “activist” even the correct word for someone who risks his or her life breaking the Fugitive Slave Act to help runaway slaves escape to freedom? What do we call a Holocaust survivor who works to prevent genocide? What do we call a black mother who has lost a son or daughter to police violence and who is doing everything in her power to prevent it from happening to someone else? What do we call a white middle-class activist participating in the Black Lives Matter movement? Whatever we call them, we need them. They offer a counterbalance to greed, hate, intolerance, and war. Without them we are doomed.

So why do many people question activists and completely disregard what they do? As stated above, the goals of social moments often require many years, even decades, before they are realized. Historical amnesia sets in when an entire generation passes before results are felt. This causes the very people who reap the benefits of social movements to forget where those benefits come from. Women alive today, for example, have always had the right to vote. This makes it easy for them to take that right for granted, and it is even easier for them to overlook the struggle it took to win that right. Likewise, the struggle of labor unions and their achievements have been almost entirely erased from the American consciousness. Days off, workplace safety laws, and higher wages are taken for granted by generations of workers that have not experienced harsh working conditions that unions worked to improve.

This amnesia diminishes the faith and knowledge that social activism works, which reduces participation and interest in social movements. As a consequence political space is opened for corporations and the government to dismantle achievements won by previous generations. Abortion rights are taken for granted when the struggle to achieve that right is forgotten. The consequence is that the right to choose is being slowly taken away from women living in states that are closing abortion clinics. The right to vote is taken for granted when the struggle to achieve that right is forgotten. As a consequence, the Voting Rights Act of 1964 is being tested with new restrictive voter identification laws that seek to disenfranchise voters. Remembering social movements is critical if we hope to maintain our rights or obtain new ones. History not only gives us an understanding of where our freedoms and living standards come from, but it also gives us tools to preserve our rights in the present, as well as a template to enact social change in the future.

Activists are driven by many things: faith that what they do will create better living conditions for future generations, historical understanding that nonviolent civil disobedience works, and unique experiences and personality traits. Ultimately, activists do what they do because it works. Bree Newsome taking down a Confederate flag is no different than Rosa Park refusing to give up her seat on a bus. Rappelling off a bridge to delay arctic drilling is equivalent to activists sitting down at a Woolworth counter and refusing to move until they are served. To casual observers, these might be meaningless stunts that do nothing more than cause trouble and get attention, but activists know that each act, along with millions of others, is part of a lager social movement that creates change.

Nauseated by the

vile corporate media?

Had enough of their lies, escapism,

omissions and relentless manipulation?

Send a donation to

The Greanville Post–or

But be sure to support YOUR media.

If you don’t, who will?