![]()

OPEDS

Bob Treasure, The Guardian, Australia

Ever since the People’s’ Republic of China invited foreign capital into the country and behind the “Bamboo Curtain”, China has been dismissed by most Left observers as selling out to capitalism and class society, with all its associated evils.

Of course capitalist commentators and “expert” economists gloat over the Chinese renunciation of socialist principles and their craven debt to neo-liberal market economics. “Proof that socialism is dead”, they say.

But China’s rapid and successful response to the capitalist Global Financial Crisis (GFC) has obliged a serious rethink of such knee-jerk assessments. Clearly China has, against all the doomsayers’ predictions, survived a crisis within which their neo-liberal “betters” in Europe and the USA are drowning, and the economic miracle continues. Maybe the “Chinese Economic Miracle” is not as capitalist as most westerners think.

Building a Platform

First, what most pro-capitalist China experts ignore is the infrastructural platform built by socialism prior to the Great Leap of the past 30 years.

When the Chinese Communist Party under Mao’s leadership assumed control in 1949 the Chinese economy was a basket-case: industry was primarily on the coast, under foreign ownership, and profits drained straight out of the country – China was bereft of foreign reserves. Her people suffered the extremes of natural disasters, and simply died in their millions when famine or floods struck. The sale and dumping of unwanted children was commonplace. Health care and education remained the preserve of the wealthy classes, and did not exist in remote rural areas. Inflation ran at 1,000 percent.

One of the first measures undertaken by the new socialist state was basic health care. The immediate result was a population boom: between 1949 and 1953 population grew from an estimated 450-500 million to 583 million – by the 1990s this figure had doubled, simply because basic health care measures (clean water, proper birth supervision, and regular check ups) were carried out. Literacy, at a level of five percent in the countryside in 1949, had become universal by the 1960s because village schools serviced all levels of the population.

Using revolutionary enthusiasm and mass organisation, huge public works in irrigation, building and electrification brought stability to agriculture and successfully fed the burgeoning population mentioned earlier. Investment in heavy industry and transport covered the length and breadth of China: the first Five Year Plan saw production double for coal, cement and machine tools, treble for oil and quadruple for steel, which reached an output of 5.3 million tonnes. By international comparison this was still small, compared with Britain’s 20 million and the USA’s 100 million tonnes, but the base from which to start was pathetically tiny to begin with.

Revisionism

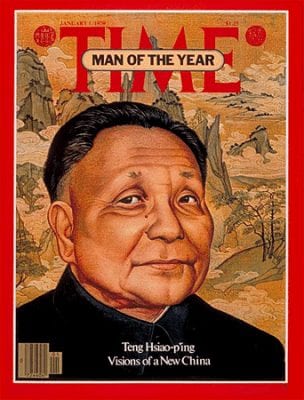

Upon his death in 1976, Mao’s dream of China’s Great Leap had not been realised, despite several attempts. After his death, a profound ideological struggle took place in the Party, between those on the “Hard Left” (led by the so called Gang of Four) who placed primary stress on a politically driven Chinese road to socialism, and the “Moderates” who were deeply materialist and favoured “Expertness” over “Redness”.

There were good reasons for revision of the dream. Since its inception China’s revolution had been isolated from the rest of the world. This was hardly China’s fault, but was instead the result of deliberate US and OECD policy, rather like its current blockade of Cuba. When its dispute with the Soviet Union denied it the know-how of the socialist bloc states, China’s economic progress was left entirely to its own devices. Despite impressive achievements, the Chinese people were not going to wait several generations for the dream of economic wealth and global leadership, as the “Middle Kingdom” had once possessed before the onset of the modern era, and which the Communist Party had basically promised as its most fundamental revolutionary platform.

Deng Xiao ping: The legendary and at one time controversial capitalist roader may have sealed China’s Faustian bargain with capitalism, but the final chapter is yet to be written. The capitalist media, sensing a friend of corporatism, soon rallied to blow kisses in his direction.

Deng Xiaoping and his faction had to address the deeper Marxist problem: that the transition from a rural/peasant political economy to modern industrial socialism was difficult, if not impossible, without the intervening stage of industrial capitalism. The foundations were there: a stable infrastructure, an educated workforce, a basic industrial capacity eager to adopt the latest technology to improve productivity, and savings for investment. By 1979, the Chinese people were sufficiently well off to squirrel away 32 percent of GDP as savings – one of the highest rates in the world at that time!

“Riding the Tiger”

Despite diplomatic recognition by the West in the 1970s, China under Maoist leadership continued to keep capitalist influence at arm’s length, and intensified its hostility towards the Soviet Union. But the dominance of Deng Xiaoping’s ideas by 1979 saw immediate revisionist changes: peasants who achieved a surplus could exchange this on open markets (higher production was urged on by State supplied price incentives), and western capitalists were invited to invest/set up industries in Special Economic Zones in four select coastal regions.

Over time, restrictions on western capitalist investment in the interior were relaxed, and ambitious Chinese, encouraged with the slogan “To get rich is glorious”, began to start their own capitalist enterprises and parade all the trappings of a home-grown bourgeoisie.

By the early 2000s there were more Chinese millionaires than people in Australia. At the same time, rural collectives and communes had been gradually dismantled, creating a widening gap between an expanding gentry and small land-leasing peasants (leasing from the State). Direct foreign investment in China grew from US$636 million in 1983 to US$616 billion in 2004.

The outcome is history, known to most people in the world. The boom commenced and continued at roughly 10 percent + per annum GDP growth from the early 1980s to the present. At this point it might be safe to assume that the Chinese CP leadership had ridden a tiger that could now devour them. By the year 2000, capitalist private enterprises were outstripping so called “inefficient” State industries and it was surely only a matter of time before the “socialist” side of the economy would be swamped.

A Lesson from Eurocommunism

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]ooking back, it is hard to imagine the Chinese Communist Party being so naive as to ride a tiger they did not believe they could control. From the outset, Deng had always maintained that the Party’s reforms were a specifically Chinese road to socialism, and subsequent leaderships have echoed the same position. On closer examination, they may well have been correct.

At no stage over the past 30 years has the State relinquished control of the “commanding heights” or “levers” of the Chinese economy: agricultural pricing, heavy industry, power and energy, transport, communications, foreign trade, and finance (state banks). This is something Lenin pursued during the New Economic Policy and the various Eurocommunist parties demanded in the 1980s. Throughout, the State has directly owned more than 50 percent of all industry (mainly through State Owned Enterprises or SOEs), and holds more than a significant interest in many so called “private” enterprises and foreign ventures as well.

Such direct State intervention has allowed China to respond to the Global Financial Crisis more rapidly and effectively than any OECD country. Fiscally, they did not have to go through the rigmarole experienced by the Rudd Labor government in carrying out their stimulus package. Here (Australia), Commonwealth funds were doled out to shonky private contractors to install insulation batts and build school halls — it took precious time to set up the contracts and ensure the contractors followed the right guidelines. In the end, it was clear the government had no real supervisory control.

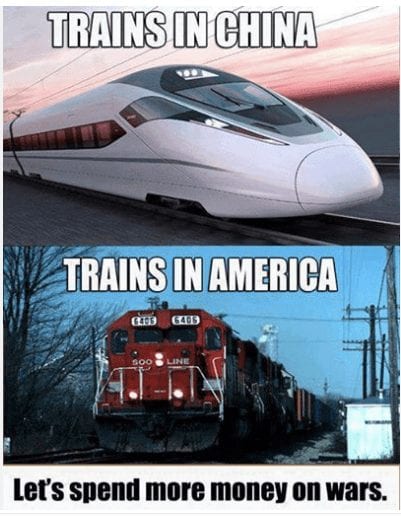

Contrast this with the efficiency of China’s response. Realising their export economy was at risk, the State shifted massive funds directly to sorely needed infrastructure in western/interior regions – railways, roads, schools, hospitals, apartments. Workers’ pay was increased, providing immediate domestic demand – not delayed, but immediate.

Monetarily, the policies were even more startling. The banks in China are state banks and they adhere to State policy. Their finances are backed by government guarantee. Over recent years these banks financed the expansion and modernisation of State enterprises (in preference to private ones) which then bought out failing private companies! “Foul!” cried the Western capitalist experts. “How dare banks operate in this way! It’s unfair!”

At present the size and scope of State-owned Chinese corporations are sending shivers down many a capitalist spine. Several are investing overseas and taking advantage of the falling values of Western companies suffering under the GFC. Last year, Chinalco’s US$23 billion offer to partner Rio Tinto was blocked by the Australian government for “commercial reasons”. Many local magnates are now demanding protection from Chinese takeovers “in the national interest”. And who should “protect” them from the international marketplace? Why, none other than the government, of course.

How Are They Doing It? Some Examples

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]riting in the Sydney Morning Herald, John Garnaut outlined the progress of RailCorp NSW’s contract for 78 double-decker eight-carriage Waratah trains with a firm called Downer EDI. This company is one of Australia’s “Top 100”, but basically it just designed the Waratah and outsourced the actual manufacture of carriages to China Railway Vehicles Co, a huge State Owned Enterprise, and part of the massive ‘Ministry of Railways’. Why?

In 2007 China had planned to lay 13,000 kilometres of high speed (faster than 350 km/h) railway by 2020, but the Global Financial Crisis intervened so the target date was brought forward by eight years, to 2012. The World Bank described the project as “the biggest single planned program of passenger rail investment there has ever been in one country” and China Railway was a big part of the nation-wide project. It rapidly gained State Bank funds to construct a purpose-built 9,000 square metre factory in Changchun, a city in far northern China – completed in seven months. The main purpose of the state-of-the-art facility was to build bullet-train carriages at $4.7 million per unit, but they are doing the Australian contract for $240,000 each – a total of $150 million.

Downer EDI gained the RailCorp contract for $3.8 billion – very neat. But who, in the long run, develops the skills, infrastructure and state-of-the-art technology for 21st century transportation? A Chinese SOE, part of a Public Ministry employing two and a half million people, that’s who.

Desperate to regain global market-share General Motors joined the Shanghai Automotive Industry Corporation (SAIC) some years ago in a 50-50 partnership to construct and market jointly-designed low cost cars and mini-vans. Last year the partnership sold over a million vehicles in China, but GM’s (domestic) financial woes obliged it to sell one percent of the partnership to SAIC to gain some ready cash. Effectively, now, SAIC has the controlling interest in a sophisticated automotive company with a very optimistic future.

In the early 2000s, a group of enterprising private investors decided to reopen some oil wells in Shaanxi province, and scored a killing when the global oil price soared. The State authorities were not happy with the attitude of the company and the self-interested way they accumulated their profits, so the China National Petroleum Corporation “renationalised” the wells last year “in the interests of the whole community”. This action inspired howls of outrage from scores of Western “democratic” observers. If only Rudd had such capacity in dealing with the Australian mining magnates!

Few statesmen on the world scene—except for Putin—compare to China’s leader Xi Jinping in terms of overall quality, vision and maturity.

China is not marking time in its grasp of “imported” technology and know-how. Chinese education has truly blossomed, and Research and Development comprise a far larger component of investment than Australia’s, for example. The SOE Telco Huawei typically allocates 10 percent of its annual investment to research and development, with the likelihood that China will soon surpass Japan and Korea in leadership of the telecommunications sector. China already leads the way in alternative energy development and implementation, and is producing the most energy efficient voltaic batteries on the planet. Overall, the People’s Republic rates second in the OECD in its commitment to research and development.

Downside/Upside

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]here are aspects to this economic roller-coaster ride that would make a socialist weep. Class society has returned with all its consequences, and is plain for all to see: rising crime, corruption, periodic and regional unemployment (although there is a desperate shortage of skilled labour), sweatshop conditions (mainly among the fully private industries so fulsomely supported by Western experts), and a growing stress upon individual appearances. It is simply tragic to see Chinese kids aping their American counterparts in their cynicism and slavish adoption of ‘hood habits, their once honest and unselfish innocence lost forever.

The rapid trend toward urbanisation has left many agrarian areas behind and created the same traffic and pollution/greenhouse problems suffered by the West – cities seem to create an alienation and social psychosis that have universal characteristics. But it has to be said that the Chinese State appears to be more responsive than most when it comes to being aware and addressing these problems.

Despite being persistently charged with “authoritarian” and “bureaucratic” practices, the People’s Republic acts more decisively than most liberal democratic governments when issues arise: whether it be natural disasters (floods or earthquakes), popular protests over inappropriate developments, corruption among Party officials, pollution or traffic gridlock, the Party/State leadership is generally on hand to respond and take immediate action. In fact, the People’s Republic has probably handled the agonising transition from rural to urban society more sensitively and effectively than any other emerging industrial power (eg Britain, USA or Japan – all of which relied on war and imperialism to establish their credentials).

As a global player, China has stopped US imperialism in its tracks, at least in Asia. In a sense, China’s industrial size (it is now the second biggest economy in the world) and its surfeit of US dollars means that its decisions determine whether, and how, the USA might be saved from its chronic debt crisis.

The People’s Republic has sustained its obligations to socialist states. Its trade with Cuba has quietly expanded, despite the embargo, to the value of US$3 billion (making it Cuba’s second largest trading partner after Venezuela) through mutually beneficial arrangements: Cuba’s public transport has benefited with the injection of 1,000 buses and numerous locomotives, in exchange for sugar, nickel and other raw materials. Venezuela’s oil has found a ready market in China, and their trade worth stands at US$8 billion. There have been further investments in other progressive Latin American states such as Brazil and Bolivia, as well as with struggling African countries.

The big difference between Chinese and US investment is that the Chinese generally provides socially useful development, whereas the Western contribution tends to be in rotgut food franchises, rip-out mining ventures, and decadent cultural consumables (eg porn and video games). In spite of historical conflicts, Vietnam has benefited by simply being a neighbour to the booming tiger: its growth too, has been substantial, though under somewhat more State supervision than the Chinese.

Conclusion

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he fact of China’s continued economic success is a powerful indicator that this experiment is at least, very different. Different to the usual capitalist “cycle” and different to past socialist experience. The much vaunted and oft forecast “crash”, recession, or exploding inflation, has simply not occurred, and continues to perplex and embarrass that vast array of Western experts who wait on the sidelines, with slavering expectation, for the People’s Republic, this festering sore in their neo-liberal sights, to come tumbling down.

So, to the original question, it is clear that the People’s Republic of China possesses a “mixed” political economy, both capitalist and socialist, not hugely dissimilar to those that existed in many Western countries during times of crisis (eg Australia during WW2) or enlightened social democracy (Scandinavia during the 50s and 60s), when the State held power that matched the capitalist ruling class. The major difference is that China has had a revolution that swept the ruling class from power, and maintains the political rule of the party that achieved this considerable feat: the Chinese Communist Party, with at least a considerable part of its membership retaining a vision of workable socialism, and ultimately, communism.

In a sense, the capitalist component of Chinese political economy is only there under sufferance. Feasibly, the Chinese State could do, in some future crisis or circumstance, exactly what it did in Shaanxi province: renationalise industry. They have always maintained that they are engaged in a “stage”, a stage that could well see the world approach a highly monopolised level of automated capitalist production. At that stage, when work feasibly could be more a matter of creative satisfaction than survival, it may well be optimal to metaphorically “lop off” the heads of private ownership and resume their companies to ensure a commonly shared distribution of wealth, for the benefit of all.

In any case, it would appear that we have relied far too much on hostile Western analysts, people who have already proved their incapacity to predict such things as the Global Financial Crisis, and who are bereft of solutions to it, without taking into account what the Chinese themselves are saying. Perhaps we need to take the Chinese perspective far more seriously if we are to arrive at a more accurate, and indeed, more optimistic, assessment.

The following is a statement made by Ai Ping, CPC delegate to the 11th International Meeting of Communist Parties held in New Delhi last year. It is well worth remembering:

“Some parties, due to lack of knowledge about the national conditions of China, think that China has given up Marxism and has deviated from the socialist path, and some even call China’s system ‘authoritarian capitalism’. But these accusations are not true… The CPC has always upheld Marxism as our fundamental guiding ideology, insisted in adapting the basic tenets of Marxism to Chinese conditions and the features of the times and tried to explore a new road for building socialism.

“CPC leaders of successive generations have pooled the wisdom of the whole party, drawn upon the experiences and lessons of other countries and established a system of theories of socialism with Chinese characteristics. In the way of exploration, the CPC as the ruling party must learn from all the excellent achievements of human civilisation, including means and management systems which can reflect the laws governing modern social production such as the capitalist market economic system.

“However, this doesn’t mean that we are pursuing capitalism, let alone changing into it. On the contrary, our purpose is to improve, consolidate and develop socialism. I am convinced that the unremitting exploration of the Chinese communists, their success in building a stronger China can not only help enrich and develop Marxism, but also encourage and inspire communists across the world to stick to socialism. This, I believe, will be a great contribution to the international socialist movement.”

Note to Commenters

Due to severe hacking attacks in the recent past that brought our site down for up to 11 days with considerable loss of circulation, we exercise extreme caution in the comments we publish, as the comment box has been one of the main arteries to inject malicious code. Because of that comments may not appear immediately, but rest assured that if you are a legitimate commenter your opinion will be published within 24 hours. If your comment fails to appear, and you wish to reach us directly, send us a mail at: editor@greanvillepost.com

We apologize for this inconvenience.

![]() Nauseated by the

Nauseated by the

vile corporate media?

Had enough of their lies, escapism,

omissions and relentless manipulation?

Send a donation to

The Greanville Post–or

But be sure to support YOUR media.

If you don’t, who will?