NOTE: Edward Said wrote a new preface for the twenty-fifth anniversary edition of his classic book, ORIENTALISM, originally published in the USA by Random House in 1978. In the following pages I have quoted some of the author’s major thoughts and added my own ideas about Said’s preface written in 2003 for the last Vintage Books edition of his magnificent work.

In Edward Said’s preface to the 25th anniversary edition of his magisterial work, Orientalism, the author rapidly begins his definition of the Orientalism that has resulted from the “immense distortion introduced by the empire (of imperialism) into the lives of ‘lesser’ peoples and ‘subject races’…. How little it wishes to face the long succession of years through which empire continues to work its way in the lives of, say, Palestinians or Congolese or Algerians or Iraqis.”

For Said, the West’s Orientalist line begins with Napoleon’s entry into Egypt two centuries ago, continues with the rise of Oriental studies (one of the author’s principle targets) and the takeover of North Africa, and goes on to similar undertakings in Vietnam, in Egypt, in Palestine and during the entire twentieth century in the struggle over oil and strategic control in the Gulf, in Iraq, Syria, Palestine, and Afghanistan. The author poses the question that if the Holocaust has permanently altered the consciousness of our time, then why do we (the imperialist West) not afford the same recognition to what imperialism has done, and what “Orientalism” continues to do.”

Here I stray from the Preface and look ahead to the book text itself to the point Said lists three major forms taken by Western Orientalism beginning with the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt, “the very model of a truly scientific appropriation of one culture by another, apparently a stronger one,” which set in motion “processes between East and West that still dominate our contemporary cultural and political perspectives.” In nineteenth century Europe a vast body of literature about the East was generated which created a new awareness of the Orient in the West which in turn was translated as a new relationship between the Orient and the West.

The second form of Orientalism was the modernization of knowledge in the West about the Orient. Oriental societies and university departments of Oriental studies spread across Europe to disseminate the new “knowledge” about the Orient. Then in the third form in which Orientalism existed, limits were fixed as to what the more creative Westerners could experience or even say about the Orient. “For Orientalism,” Said proposes, “is ultimately a political vision of reality whose structure promotes the difference between the familiar (Europe, the West, “us”) and the strange (the Orient, the East, “them”). This vision in a sense created and then served the two worlds thus conceived: Orientals lived in their world; “we” lived in ours.”

The result was that the stronger of the two, the West, could penetrate (also imperialistically) and give meaning to the great “mysteries” of the East. Said’s argument is that precisely such a vision of the East vision has made Orientalist reality, its vast institutions and all-pervasive influence, “both inhuman and persistent” up to the present.

This vision of the state of relations between East and West between scholars and intellectuals on the one hand and national states (and blocks of nations) and their peoples and their religions on the other, is disheartening and frustrating for a person, especially a thinking and caring person, who belonged to both worlds as did Said. His preface—actually also his entire book—is thus a challenge to scholars, in his words “to use humanistic critique to open up the fields of struggle” between East and West in place of the polemics and antagonisms that prevent mutual comprehension one of the other.

The author holds steadfastly to his humanistic method chiefly because he truly believes that “nothing that goes on in our world has ever been isolated and pure of any outside influence.” For him the discouraging part of such considerations is that the more cultural studies show that such is the case, the less influence it has in East and West. The emergence of the explosive territorial-religious-social-political polarizations we know today offer us the bitter confirmation of the state of relations between two irrational and apparently irreconcilable antagonists today faced with the reality of “Islam versus the West.”

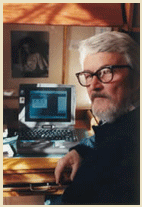

The controversial world-famous scholar and writer and leading U.S. advocate of the Palestinian cause, Edward Said, died of leukemia in New York on September 25, 2003 at age 67. He had signed this new preface to Orientalism in May, 2003, obviously, aware that he had little time to state his case in full. Born in 1935 in Jerusalem, then part of British-ruled Palestine, he was raised in Egypt before moving to the United States as a student. In that sense he lived a pluri-cultural life: Islam and the West. Therefore, he felt a special moral responsibility in the use he made of his particular life experience and abilities.

His passion literally exudes from most every line of the sixteen pages of one of his last major writings. He emphasizes the “vital necessity for independent intellectuals to provide alternative models to the reductively simplifying and confining ones, based on mutual hostility, that have prevailed in the Middle East and elsewhere for so long.”

Said, a professor of comparative literature at Columbia University and not of Arab or Islamic studies as one might expect, was a harsh critic of Israel for its mistreatment of the Palestinians. In the name of academic freedom, Columbia did not censure him when he created international controversy like the time he demonstratively threw a rock toward an Israeli guardhouse on the Lebanese border. As to his ability to interpret political events, he wrote after visits to Jerusalem and the West Bank that Israel’s xenophobia toward Arabs had strengthened Palestinian determination. In general, his outspoken stance made him many enemies and he received many death threats; his office was set on fire and the Jewish Defense League labeled him a Nazi.

Said does not mince words in this preface, signed three months before his passing. Speaking as both American and Arab he advises against underestimating the simplified views of the world formulated by a few Pentagon civilian elites for U.S. policies in the Arab/Islamic world. He charges the media for its endlessly debating of policies based on terror, preemptive war, and unilateral regime change backed up by “the most bloated military budget in history” and for assigning itself “the role of producing so-called ‘experts’ who validate the government’s general line. Likewise, he accuses Americans in general for not generating “enough dissent from the dubious thesis that military power alone can change the map of the world.”

“The breath-taking insouciance of jejune publicists who speak in the name of foreign policy and who have no live notion (or any knowledge at all) of the language of what real people actually speak has fabricated an arid landscape ready for American power to construct there an ersatz model of free market ‘democracy’….” Said explains that he means the difference between knowledge of other peoples and other times that results from understanding, compassion and careful study and analysis and on the other hand, knowledge that is part of an overall campaign for self-affirmation, belligerency and outright war.

Excusing himself (needlessly in my opinion) for too many abrupt transitions between humanistic interpretation on the one hand and foreign policy on the other, and his refusal to accept that a modern technological society that, along with unprecedented power, possesses the internet and F-16 fighter jets, must be in the end commanded by formidable technical-policy experts like Donald Rumsfeld,

Said writes a five-liner denunciation of American ideology that I consider morally exemplary of his thinking: “Reflection, debate, rational argument, moral principle based on a secular notion that human beings must create their own history have been replaced by abstract ideas that celebrate American and Western exceptionalism, denigrate the relevance of context, and regard other cultures with derisive contempt…. But what has really been lost is a sense of the density and interdependence of human life.”

As could be expected, the book, Orientalism .stirred up a hornet’s nest in the field of Middle Eastern Studies. Roger Owen, Professor of Middle East History at Harvard University, a “good” Orientalist according to Said’s definition, notes the personal tone in Said’s book: the author’s origins, his reasons for writing the book, his genuine offense at the objectification of Arabs and Muslims. Owen notes that parts of the book are read as political and polemical rather than “scholarly and academic,” a no-no in the academic world. Said’s words are actually more than criticism; they are an accusation that was answered chiefly by counter-accusations which “muddied” the oh so sensitive academic waters.

Said’s Orientalism thus continues to be regarded as dangerous, in particular by those who have perhaps never read it, like State Department Arabists. Hence, the polarization in the field of Modern Middle Eastern studies: the followers of Edward Said on the one hand and those, for example, belonging to the Middle East Studies Association on the other. Said’s critics claim the attacks on Said and his followers (caused by Said himself and his book) make it more difficult for “good” Orientalists to sustain an attack on the role of (“bad” and guilty) Orientalists in authorizing not only American military and security policy but those of Israel as well. It is my view that academia, in its genteel-acidic manner, is attempting to shift the blame onto Edward Said’s shoulders for their kowtowing to political power.

EDWARD W SAID, PARIS, FRANCE – NOV 1996…Mandatory Credit: Photo by Sipa Press / Rex Features ( 408195b )

EDWARD W SAID, PARIS, FRANCE – NOV 1996

Said then concludes his imaginative-interpretive essay-preface twice. His first conclusion is to insist “that the terrible reductive conflicts that herd people under falsely unifying rubrics like ‘America’, ‘the West’, or ‘Islam’ and invent collective identities for large numbers of individuals who are actually quite diverse cannot remain as potent as they are, and must be opposed, their murderous effectiveness vastly reduced in influence and mobilizing power.”

“And lastly,” the author writes, “most important, humanism is the only, and I would go so far as to say, the final resistance we have against the inhuman practices and injustices that disfigure human history. We are today abetted by the enormously encouraging democratic field of cyberspace, open to all users in ways undreamed of by earlier generations either of tyrants or of orthodoxies. The world-wide protest before the war began in Iraq would not have been possible were it not for the existence of alternative communities across the globe, informed by alternative news sources, and keenly aware of the environmental, human rights, and libertarian impulses that bind us together in this tiny planet.”

Senior Editor Gaither Stewart, based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

Senior Editor Gaither Stewart, based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.