Animals: Who’s to Blame for Harambe’s Death—and What Can Be Done to Avoid Such Unnecessary Killings?

ENVIRONMENT

In the end, Harambe’s own sense of security was violated.

By Marc Bekoff / AlterNet

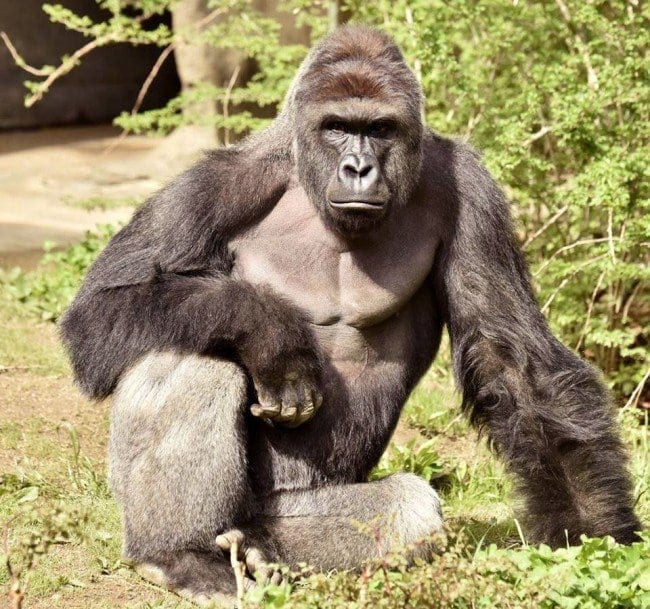

Many people worldwide already know about the shooting of a 17-year-old male western lowland gorilla named Harambe at the Cincinnati Zoo to save the life of a four-year old child who fell into the gorilla’s cage. The boy apparently told his mother he wanted to meet Harambe and crawled under a rail and over the wall of the moat. As usual, my inbox was ringing constantly with different reports of Harambe’s killing, some might call it an execution or a murder. Indeed, the title of Peter Holley’s essay in the Washington Post is called “Shooting an endangered animal is worse than murder’: Grief over gorilla’s death turns to outrage.”

Who’s to blame and what can be done to avoid such unnecessary killings?

Opinions vary widely about whether or not the boy’s parents are to blame and should be charged for negligence, and whether Harambe should have been killed, as there is essentially no evidence that the gorilla was going to harm the child. As I watched footage of the event I was reminded of an incident at Chicago’s Brookfield Zoo in which a female western lowland gorilla named Binta Jua rescued a three-year old boy who fell into her enclosure.

We can also ask if the zoo is to blame. Why was the boy able to get under the rail, had zoo workers practiced the sorts of rescues brought on by these events, why wasn’t Harambe tranquilized?

Moving forward, caretakers, who are responsible for the day-to-day well-being of the zoo’s residents and who form personal relationships with them, must be involved in preparing for emergency situations such as this. It’s these people “on the ground” who know the animals the best and who regularly communicate with them. They also could well be the people who could communicate the animal out of danger so it could be a win-win for all involved. Harambe, like all other gorillas and numerous other zoo-ed animals, are highly intelligent and emotional beings who depend on us to respect and value their cognitive capacities that could well be put to use in potentially dangerous situations. Clearly, knowing about the behavior of each animal, as an individual with a unique personality, is essential for the well-being of every captive being.

We can’t undo Harambe’s death but we can, and must, ask these sorts of questions. We also must be sure that all zoo personnel are prepared for unexpected emergencies and are adequately trained to respond where lives are on the line, because killing Harambe is a tragedy that could have been avoided.

Analyzing Harambe’s behavior after he met the child

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]here seems to be no reason to think that Harambe was going to harm the young boy who fell into his enclosure. I know how serious this situation is so let me be clear that thisis a horrible situation and I know that people make split decisions they often come to regret. But I still am not convinced that Harambe could not have been tranquilized and that regular rescue drills centering on this sort of event could have resulted in Harambe still being alive and the little boy being returned to safety.

SIDEBAR

Hanna agrees “1000%” with Zoo officials’ decision

[dropcap]I[/dropcap] don’t know much more about the behavior of gorillas than I read in texts and research papers, so I asked my friend Jennifer Miller some questions, as she has worked with these amazing beings. Jennifer wrote in an email, “Harambe’s movements and positions during the encounter presented nothing more than curiosity and protection for an unfamiliar child inside his environment. What I learned from studying captive Western Lowland gorillas at the Cleveland Zoo was that they are deep contemplators. They are observers more than reactive aggressors. They move their eyes, lips, and heads slowly to communicate through subtle movements. They are rarely vocal and rarely dramatically expressive. Even when threatened by other gorillas, an individual will choose to avoid confrontation more often than engage in harmful behaviors. In avoidance gorillas often run past other individuals beating their chest, stand still on all four limbs biting their lips or they will hit a wall/tree/anything close and then run off. The only protection that Harambe had that day was the zoo enclosure he was locked into. That protection was violated by the human public, at which point Harambe became unprotected and was more at risk than the child. He did not stand a chance at human forgiveness as soon as the child entered his enclosure. And the proof lays in the bullet that shot him dead.”

Ms. Miller goes on, “Harambe’s hold on the child and his sheltering of the child inside his stance, are all indications of protection. Harambe did not view this most unexpected encounter through a lens of fear. Not only was Harambe examining the child in front of him but he was also attentive to the other changes in his environment – the movement of the crowd, the communication between mother and child, the positioning of strangers in areas of his exhibit where they are not normally.”

I’m thrilled that the four-year old boy survived, but like many others, I too wonder why Harambe was killed, rather than tranquilized. I’ve listened to all of the reasons why he was killed but don’t see that it was necessary.

Why the extra media hype about killing an animal but “business as usual” for human shootouts?

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]s. Miller also noted, “Some media reports claim that Harambe aggressively dragged the child through the water. Nothing can be further from the truth. This type of behavior — ‘dragging through the water’ — is common. Adult gorillas commonly do this to one another and to their offspring, in which case the infant gorilla typically climbs up the adult to avoid the ground. A human child would not know to do this, but that does not justify defining a normal non-aggressive behavior as aggressive.”

I also am interested in how media covered this event. For example, on some national news programs on TV the evening of Sunday May 29, the story of Harambe was immediately followed by a report on a shootout in Houston, Texas in which two people were killed and six injured. What was incredibly apparent was the tone of the voice of the reporters. When Harambe’s story was told the reporter was wired and breathless as she reported the incident, noting that Harambe simply had to be killed to save the boy. When the next reporter told the story of the horrific Houston shootout her voice was calm and came across as something like, “Oh well, here we go again — another mass killing — business as usual.” I was shocked and later that evening I watched a few other news shows with the same trend being rather obvious. I talked with a few people and without exception they also saw that type of image being presented, one that surely didn’t do much for Harambe’s image.

Zoo-ed animals and their total losses of freedoms

Another point many people make is that animals like Harambe should not be kept in zoos in the first place. I totally agree, but this discussion at this point deflects attention from the event at the Cincinnati Zoo that could have and should have been avoided. In the best of all possible worlds Harambe would not have lived as a caged animal and the little boy would not have violated the safety of Harambe’s home. The case of all zoo-ed animals must be openly discussed because their lives are so horrifically compromised and numerous freedoms lost as they are forced to live in small cages for human entertainment (please see, for example, “What Zoos Need to Do for Zoo’d Animals,” “Is Going to a Zoo Like Shopping for a Car? Musical Semen,” and “What Do Zoos Teach about Biodiversity and Does it Matter?“).

All in all, Harambe’s freedoms were taken from him the moment he was born into captivity and his protection taken from him when his space was violated by human activities. While it’s most likely that Harambe and other animals kept in cages in zoos would prefer to be free, it’s also likely that he viewed his cage as his home and felt safe in familiar environs.

Let’s remember in head and heart that Harambe was killed for being forced to live in a cage for some human’s, not his own, benefit, and because it was thought hemight harm the child for coming into his home. He was killed for doing what many of us might do in a similar situation, but it still remains highly questionable that Harambe had to be killed.

Let’s be sure Harambe did not die in vain

Harambe is gone forever, but what happened to him can and must be used to make certain that events like this never happen again. As I mentioned above, there is global concern about Harambe’s death and people who never before have been involved in “animal issues” have weighed in on what happened to him. We can only hope that Harambe, like Cecil the lion who was trophy murdered by a rich dentist from the United States and Marius, a young giraffe who was killed at the Copenhagen Zoo because he was deemed to be disposable because his genes were no longer useful, will remain in people’s hearts and this will lead to a rapid termination of killing animals when it is utterly unnecessary and wrong. All sorts of media can help this movement along and foster peaceful coexistence between humans and nonhumans.

Harambe and Binta Jua revisited

In the end, Harambe’s own sense of security was violated, as was Binta Jua’s. However, Binta Jua survived and was hailed worldwide as a heroine, whereas Harambe was killed and his death is being criticized and carefully scrutinized globally. Let’s hope that something like this never happens again.

Note: Carol Gigliotti’s comment captures much of what others and I are writing about: The underlying issue is the way we treat animals in general, as objects for our use, and I felt that blaming the mother of the child, for this admittedly tragic instance, obscured and muddled that underlying issue. Breeding an animal to live out their life in a zoo, and then wondering why untoward things happen when people, in this unfortunate case, a small boy, intrude on the only home they know is the actual problem in this and many other situations involving animals.

This article was originally published on Psychology Today.

is Professor Emeritus of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He is the co-founder, with Jane Goodall, of Ethologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, a fellow of the Animal Behavior Society and a former Guggenheim fellow. Marc's latest books are Jasper's Story: Saving Moon Bears (with Jill Robinson), Ignoring Nature No More: The Case for Compassionate Conservation, Why Dogs Hump and Bees Get Depressed: The Fascinating Science of Animal Intelligence, Emotions, Friendship, and Conservation, Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence, and The Jane Effect: Celebrating Jane Goodall (edited with Dale Peterson). For more information, visit marcbekoff.com. Follow Marc on Twitter @MarcBekoff.

is Professor Emeritus of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He is the co-founder, with Jane Goodall, of Ethologists for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, a fellow of the Animal Behavior Society and a former Guggenheim fellow. Marc's latest books are Jasper's Story: Saving Moon Bears (with Jill Robinson), Ignoring Nature No More: The Case for Compassionate Conservation, Why Dogs Hump and Bees Get Depressed: The Fascinating Science of Animal Intelligence, Emotions, Friendship, and Conservation, Rewilding Our Hearts: Building Pathways of Compassion and Coexistence, and The Jane Effect: Celebrating Jane Goodall (edited with Dale Peterson). For more information, visit marcbekoff.com. Follow Marc on Twitter @MarcBekoff. APPENDIX:

Mainstream press reporting human shift in perceptions about wildlife

See below

After Harambe the gorilla shooting, how best to protect endangered species? (+video)

SHIFT IN THOUGHT

The death of the gorilla Harambe comes amid a climate of heightened public interest in how humans treat animals – both in captivity and in the wild.

A 400-pound silverback gorilla was shot and killed at the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden on Saturday after a little boy fell into the animal’s enclosure.

Zoo officials said they made the “difficult” decision because the gorilla, a 17-year-old named Harambe, was acting erratically toward the child and seemed agitated by the cries of onlookers.

The tragedy ignited a public outcry over the weekend, with both zoo officials and the child’s parents blamed for the death of Harambe. But for some experts, the incident raised more important questions about the role of zoos more generally in preserving and rebuilding endangered species.

Recommended: Name that animal!

“Playing the blame game just isn’t going to get us anywhere,” says Marc Bekoff, renowned ethologist and a fellow for the Animal Behavior Society.

Harambe’s death has come amid a climate of heightened public interest in how humans treat animals – both in captivity and in the wild. A shifting understanding in the United States about the needs of individual animals, stoked by documentaries such as “An Apology for Elephants” and “Blackfish,” have caused organizations such as Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus and SeaWorld to back away from showcasing large mammals as entertainment. Wildlife poaching, meanwhile, has become a cause du jour for celebrities and governments.

The role of zoos is a more complicated topic, however. On the one hand, they keep animals in captivity. On the other, they promote worldwide conservation efforts and work to preserve critically endangered species, like the western lowland gorilla. The question for some ethicists is whether the resources being spent to house and care for animals would be better spent supporting populations in the wild.

“The real issue we’re talking about is whether or not we’re justified keeping gorillas in captivity ongoing, and my argument is no,” says Lori Gruen, a professor of philosophy and co-coordinator of Wesleyan Animal Studies at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn. “We should be taking the best care of captive gorillas, but [also] providing support for wild gorillas to live out their lives in the wild.”

Many zoos are already doing both these things, however, including the Cincinnati Zoo. The zoo says it has been funding gorilla conservation projects in the Republic of Congo for 15 years among other initiatives, including a cell phone recycling project aimed at reducing demand for coltan, a mineral used in cell phones that is mined in gorilla habitat.

The nonprofit Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), which accredits and sets guidelines for zoos around the country, argues that zoos play a vital role in educating visitors about wild animals and conservation issues.

“Western lowland gorillas are critically endangered animals, so anything that can be done to help conserve their species must be done at this point. AZA-accredited zoos play an important role in that effort not only through the Species Survival Plan program, but also through supporting field conservation work,” says Rob Vernon, communications director of the AZA, in an e-mail. “Between 2010 and 2014, AZA members contributed over $4.5 million to gorilla field conservation work. Gorillas are also one of the 10 signature species part of the SAFE: Saving Animals From Extinction effort that AZA members and partners are combining resources and leadership to save these great apes.”

Researchers affiliated with the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago are leading a long-term study of gorillas in the Goualougo Triangle, a remote region of the Republic of Congo. The Bronx Zoo has raised more than $12 million for conservation programs through admission fees to its Congo Gorilla Forest, a 6.5-acre rain forest that is home to about 20 western lowland gorillas.

None of that good work helped Harambe, however, says Professor Gruen.

“Why are we in a situation in which the choice has to be made between a highly endangered animal and a 4-year-old child?” she says. “It’s only because we have a highly endangered animal in zoo setting, otherwise the choice wouldn’t have to be made.”

Harambe was brought to the Cincinnati Zoo in 2015 to breed with other gorillas, but she notes that, since gorillas bred in captivity can never be released into the wild, expanding captive gorilla populations will do nothing to help wild gorillas under threat from poaching and habitat loss and fragmentation.

“We’re engaged in a process where we’re going to perpetuate captive gorilla populations that will never be able to returned to wild,” she says.

“The idea that gorillas are somehow ambassadors to the wild and will someday return, that’s not correct,” she adds. “The goal should be to provide the best captive care for gorillas … and protecting and preserving wild gorillas.”

Reformers instead say that zoos should follow an increasingly popular “compassionate conservation” approach that uses large sanctuaries, strictly limiting human interaction, to focus on rehabilitation.

“We tried to build something more enriched – a happy resting ground for all of [these animals],” Ed Stewart, who co-founded one such sanctuary in California, told the Monitor in February. “But it’s still a step way down from the wild.”

Animal ethicists say they hope that the public continues to ask questions about how best to protect and care for endangered species in the wake of the weekend tragedy in Cincinnati.

“To me the major question is: Why was Harambe there in the first place?” says Dr. Bekoff, a former professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “We can’t bring Harambe back, and I’m thrilled the boy is safe, but I was hoping this case would make a difference, and I think it is a case that will make a difference.”

Witness behind cell phone video of Harambe supports zoo’s decision

Witness behind cell phone video of Harambe supports zoo’s decision