![]() Henry A. Giroux

Henry A. Giroux

Cultural Critic and Public Intellectual

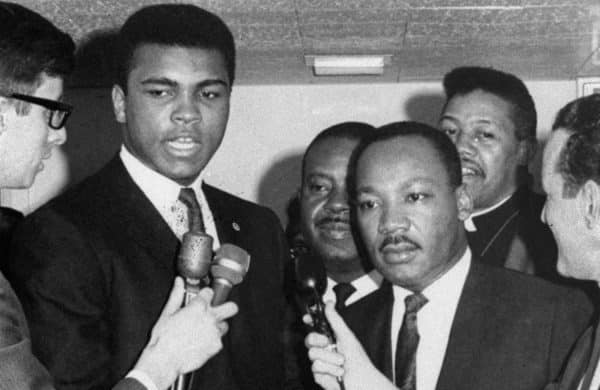

Muhammad Ali and Martin Luther King shared a deep friendship and commitment to freedom and equality. The Nation

![]() [dropcap]T[/dropcap]he death of Muhammad Ali strikes at the heart of what it means to lead a life of dignity, unsurpassed skill, and the willingness to step into history and call out its most insidious injustices. I am one of many, I am sure, whose heart is broken over the death of Muhammad Ali, who was a hero for those of us raised in the sixties and for whom he modelled that poetic dialectic between the body and a notion of resistance. For my working class generation, the body was all we had — a site of danger, hope, possibility, confusion, and dread — he elevated that understanding into the political realm by mediating those working class concerns into a brave and courageous understanding of politics as a site of resistance. He made it clear that resistance was a poetic act that was continually being written. He unsettled the racial order, protested the war, and danced in the ring like a butterfly — a master of wit, performance, and sheer courage. Resistance for Ali was not an option, but a necessity.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he death of Muhammad Ali strikes at the heart of what it means to lead a life of dignity, unsurpassed skill, and the willingness to step into history and call out its most insidious injustices. I am one of many, I am sure, whose heart is broken over the death of Muhammad Ali, who was a hero for those of us raised in the sixties and for whom he modelled that poetic dialectic between the body and a notion of resistance. For my working class generation, the body was all we had — a site of danger, hope, possibility, confusion, and dread — he elevated that understanding into the political realm by mediating those working class concerns into a brave and courageous understanding of politics as a site of resistance. He made it clear that resistance was a poetic act that was continually being written. He unsettled the racial order, protested the war, and danced in the ring like a butterfly — a master of wit, performance, and sheer courage. Resistance for Ali was not an option, but a necessity.

One of his greatest gifts was using his talent as a world-renowned fighter to flip the script, a script used by the elite of the time to define poor black and white kids by their deficits. In his speech and actions, Ali taught a generation of young kids that their deficits were actually their strengths, that is, a sense of solidarity, compassion, a merging of the mind and the body, learning and willingness to take risks, embracing passion, connecting knowledge to power, and being attentive to the injuries of others while embracing a sense of social justice. Ali taught us how to talk back to power. Many of us learned early that what Ali was saying was that we had to flip the script in order to survive and we became acutely aware that the alleged strengths of those who oppressed us in the streets, schools, on the job, and in other spaces that our bodies inhabited were actually vicious deficits, extending from their racism to their unbridled arrogance and propensity for violence. Ali provided a language and sense of agency that provided a turning point in our being able to narrate and free ourselves from one of the most sinister forms of ideological domination — what Marie Luise Knott calls “those unexamined prejudices that keep us from thinking.”

Ali was dangerous not just as a deftly skilled boxer but also because he deeply understood that challenge, if not slow process, of unlearning the poisonous sedimented histories minority youth often have to internalize and embody in order to survive. Unlearning meant becoming attentive to the histories, traditions, daily rituals, and social relations that offered both a sense of resistance and allowed people to think beyond the inflicted misery and suffering that marked their neighbourhoods and daily lives. It meant not only learning about resistance in their lost histories but also how to narrate themselves from the perspective of understanding both the toxic cultural capital that shored up racist state power and those modes of knowledge and social relations that allowed us to challenge it. It also meant unlearning those modes of oppression that too many of us had internalized, obvious examples being the rampant sexism and hypermasculinity we had been taught were matters of common sense and reputable badges of identity. But in the end, Ali taught us to believe in and fight for our convictions.

Outside of being the greatest boxer in the world, Ali sacrificed three and a half years of his career for the ideals in which he believed. He was not merely an icon of history, he helped to shape it. Ali had his flaws, and his ridicule of Joe Frazier and his disowning of Malcolm X speak to those shortcomings, but Ali was not a god, he was simply flawed differently. What is most remarkable about him as a fighter for the underdog was his ability to flip the script. It will be hard to find people like Ali in the future now that self-interest and a pathological narcissism have taken over the culture in the age of casino capitalism. I will miss him and only hope his legacy will leave the traces of resistance and courage that will inspire another generation. He was a champ in the most courageous sense who showed generations of working class kids how to resist, struggle, and talk back with dignity and grace.

![]()

Currently holds the Global TV Network Chair Professorship at McMaster University in the English and Cultural Studies Department and a Distinguished Visiting Professorship at Ryerson University. His books include: Zombie Politics and Culture in the Age of Casino Capitalism (Peter Land 2011), On Critical Pedagogy (Continuum, 2011), Twilight of the Social: Resurgent Publics in the Age of Disposability (Paradigm 2012), Disposable Youth: Racialized Memories and the Culture of Cruelty (Routledge 2012), Youth in Revolt: Reclaiming a Democratic Future (Paradigm 2013). Giroux’s most recent books are America’s Education Deficit and the War on Youth (Monthly Review Press, 2013), are Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education, America’s Disimagination Machine (City Lights) and Higher Education After Neoliberalism (Haymarket) will be published in 2014). He is also a Contributing Editor of Cyrano’s Journal Today / The Greanville Post, and member of Truthout’s Board of Directors and has his own page The Public Intellectual. His web site is www.henryagiroux.com.

Currently holds the Global TV Network Chair Professorship at McMaster University in the English and Cultural Studies Department and a Distinguished Visiting Professorship at Ryerson University. His books include: Zombie Politics and Culture in the Age of Casino Capitalism (Peter Land 2011), On Critical Pedagogy (Continuum, 2011), Twilight of the Social: Resurgent Publics in the Age of Disposability (Paradigm 2012), Disposable Youth: Racialized Memories and the Culture of Cruelty (Routledge 2012), Youth in Revolt: Reclaiming a Democratic Future (Paradigm 2013). Giroux’s most recent books are America’s Education Deficit and the War on Youth (Monthly Review Press, 2013), are Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education, America’s Disimagination Machine (City Lights) and Higher Education After Neoliberalism (Haymarket) will be published in 2014). He is also a Contributing Editor of Cyrano’s Journal Today / The Greanville Post, and member of Truthout’s Board of Directors and has his own page The Public Intellectual. His web site is www.henryagiroux.com.

Originally published: The Hamilton Spectator

=SUBSCRIBE TODAY! NOTHING TO LOSE, EVERYTHING TO GAIN.=

free • safe • invaluable