End Station Nostalgia

![]() Dispatches from

Dispatches from

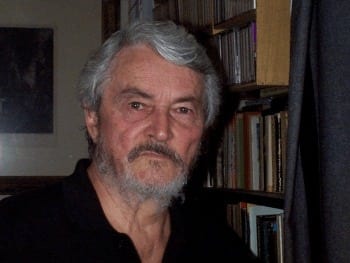

G a i t h e r

Stewart

European Correspondent • Rome

![]()

Welcome to another short story by our resident storyteller. Enjoy.

Welcome to another short story by our resident storyteller. Enjoy.

A sign hanging over the steps at the U – Bahn station at Schönhauser Allee carried the theatrical announcement, Endstation Sehnsucht. What did it mean, Sidney wondered? Nostalgia for the past? For pre – war Berlin? Or did it mean nostalgia for this neighborhood’s recent Communist times? Not everyone in former East Berlin, Sidney knew, was enamoured of globalized capitalism.

Following the sign’s arrows he entered the shopping arcades—a fruit stand at the entrance, inside, baker, fish shop, ethnic grocers, wine store, gift boutiques, clothing stores, galleries. At the rear of the third level he found the small shop he was looking for—Oggetti d’Arte e Cose Arcane, Inhaber: Conte Giuseppe Montereali.

Sidney’s heart sank when he read a handwritten sign on the window—geschlossen. The store was dark, mail stuck in the door, newspapers on the floor. His face pressed against the dusty glass he noted a faint light inside, far back in the rear. A light push and the door opened.

“Do come in … Come, come, my boy, don’t be shy!” called a voice from the shadows.

Sidney recognized the accent. Exactly like that of his paternal grandfather in New York. Italian. Again he wondered about his impulsive trip. A mysterious handwritten letter in Italian addressed to him at NYU had sufficed to bring him here just at semester’s end when he should be consulting his graduate students. Yet, his book in preparation counted more. Across the top of the one – page letter had appeared the words, LA VERITA SULLA MORTE DI MASACCIO. The dangling allusions in the brief text were enough to carry the art historian Professor Sidney Sonnino to Berlin that very same weekend.

“I am Montereali,” the man said, stepping in front of the light that illuminated his ashen face and grasping Sidney’s extended hand in both his skeletal hands.. “I assure you that you will not regret your trip!” the shrivelled man said, tilting his head backwards to look up at Sidney’s tall figure.

“Here to the crossroads of new Europe!” he added.

“How could I not come?” Sidney murmured, looking around skeptically. Was this all in vain? What secrets could be hidden here? “After all I am the Masaccio specialist.”

“Ah yes!” The tiny man smiled condescendingly, continuing to pump Sidney’s hand. His eyes mere slits under thick eyebrows, his head bald except for wisps of long hairs over huge ears, his lips turned inwards over his gums.

“Ah yes, a specialist,” he said. “O, you academics, dedicating your lives so selflessly to old truths. Ah yes! Yes, yes … but wait, let us put some light on the subject.” For a moment the old man’s Italian accent had taken on Germanic cadences as if his persona were uncertain.

“But why here? Why in Berlin?”

“The capital Europe of the future! Is that not reason enough? Everything has always been here … and will be again.”

Conte Montereali turned to the wall and flipped a switch. Light filled the room, revealing in the rear shelves of books and a desk covered in papers and folders and opened tomes piled one atop the other.

He must be a hundred years old, Sidney thought, as the old man shuffled toward the desk. He was more voice than body. Voice and eyes … and the familiar odor of private collections of ancient tomes following in his wake. That smell alone seemed a guarantee of the authenticity of his hinted revelations.

“I’m also a detective,” Sidney murmured, “an investigator of the past.”

“Yes, yes, I understand. Precisely why I approached you … I knew you would come. Did I write you that I once knew your grandfather in Rome—no, it must have been your great – grandfather, Mosé. And I have read your book, The Secret Life of Masaccio. Now, young man, you can forget Berlin for the moment, for you must learn the secrets of his death.”

“But does anyone really care?”

“Care? Anyone? I think you are now pulling my nose! If not, then you are dedicating your life to nothing … to a bagatelle. Life dedicated to nothing is nothing! But no, or rather yes, true art lovers care what happened to the artist who nearly six centuries ago liberated man from the fear of God. Who established man’s right to know and to act. It’s a question of who we are … and of why we are here. He should have been a Berliner.”

“Who should have been a Berliner?”

“Your idol! Our idol was in fact murdered by the man of the fashions of the day. The man of the Court. The man of the big commissions. He was murdered by society. Breve, I have proof that his so – called master and employer, Masolino, assassinated our hero. And I will give you that proof. You must use it wisely.”

They sat face to face in front of the desk. The powerful overhead lights blinded Sidney to the old man’s face as he recounted the story of how a jealous Masolino lured the young genius, Masaccio, to Rome, and kidnapped and poisoned him rather than face again the ridicule of popes and mecenates because his pupil outshone him.

“You should always keep in mind,” Montereali said, “that facts are not always facts.”

“But why here?” Sidney insisted. “Why are you here? Why Masaccio here?”

“Why? Berlin too is an idea. An idea and a place many have died for … even if on faraway fields.”

Uncertain of what he was to do the next two days before his return flight to New York, Sidney hung around the rail stations … his method of learning a new city. And from time to time he wondered what the old man had meant—‘facts are not always facts.’

Walking through the busy Alexander Platz Station on the late afternoon in May the proximity of Poland and East Europe was palpable. He could smell the East. The old man was right, this was a crossroads. Everyone seemed to be passing through Alexander Platz. It was a strange sensation—you couldn’t tell who was travelling just the next station or to Frankfurt an der Oder and Poland. Still, he was surprised that the platform of the Friedrichstrasse Bahnhof was less crowded than Manhattan subways stations—the S – Bahn and regional trains arrived so frequently and departed so quickly that crowds had no time to form.

Signs and placards proclaiming that ‘a better world is possible’ confirmed his ideas that Berlin was an ardent Socialist city. A city of alternative life styles. It always had been, even in the Nazi era. It didn’t seem at all German as he had expected. He didn’t feel his Jewishness here as he had feared. When people in New York had asked how he felt about going to Germany, he always answered that he tried to confront his hang – ups. Berlin, distinct from Germany, was a bridge. The city did seem like an idea. He thought the maverick Masaccio too would have felt at home here.

As time passed the encounter in the dark little shop in Prenzlauer Berg came to seem like a dream. But the contents of cardboard file case Montereali had given him were real. A researcher’s dream. A detective’s dream. He had held it on his lap on the flight back to New York and stored it in the safe in his study at the university—photocopies of documents, letters from Masaccio’s parents, bits of testimonies and police protocol written in Latin and Rome dialect, drawings allegedly by Masaccio himself, one of which autographed. The dossier was meticulously indexed and cross referenced, and arranged according to the month and year the document was obtained. It read like a detective story.

In his downtown Manhattan study Sidney came to feel like a fugitive. Berlin was strangely on his mind. It was more than Masaccio. More than Monetreali. It was Germany, the history of the twentieth century, and his place in it. He paced the room. Measured again the Turkish carpet. Looked for pertinent 15th century quotes. Examined the Tula samovar and consider wiring it electrically. Listened to the Ute Lemper recording of Berlin songs. Read at random from the Pentateuch. Moses! Moses? Anything rather than read again and again the Montereali dossier, now condensed to fit his own needs. Yet, Masaccio was his ticket. To where, he didn’t know. Too bad he didn’t know Italian better. Straight into the computer with it anyway! Do it himself. No students involved. Top secret. After the Berlin discovery, he had reduced class work to a minimum. Late evenings spent sorting and recording the data.

In July Sidney made an urgent trip to Rome to interview sources indicated by the old man. On the flight he read and re – read the end of the fictional story the old man had sent him in a supplementary file of Masaccio materials labelled “Appunti dagli Archivi di Stato, Gennaio, 1922.”

He stumbled out into the darkness. He had to get to San Clemente. Masolino was waiting. His Rome paintings were there. Everyone knew his tryptich in Santa Maria Maggiore. That knowledge helped him to stay sober and upright. It was his. He teetered and zigzagged ahead. He was drunk and sick. He headed up the hill that would take him to the security of San Clemente.

Soon he heard the shadows closing in behind him. Strong arms encircled him from behind. He felt a searing pain in his side. ‘Masolino sends this to you, upstart!’ he heard before darkness descended into his brain.

Hours, days or weeks later he awakened, dried blood in his opened clothes, rags binding his hands and feet. The room was bathed in chiaroscuro. Shadowy figures were looking down at him. Sanguinely he stared up at them and felt only the absence of his money belt. He remembered exactly how it had felt around his waist, hanging erotically toward his groin.

No matter, he thought. He didn’t feel so bad, except for that wound in his right side. But when he peered into the silence and listened to the shadows, he knew.

‘Am I a hostage?’ he asked. ‘I suppose someone will pay my ransom.’

‘We’ve been paid,’ a voice said.

‘Paid?’ Tommaso ‘Masaccio’ Guidi asked. ‘Paid? Who paid?’

‘Friends … and enemies. Both. You never know when you’re dealing with Tuscans.’

A frisson of mystery ran down his body. Mysterious like the smeared paint you find in the early morning on the canvas you worked on the night before and you recall the nocturnal nightmare of its destruction. Why that dream now? Or was it reality too? He looked at the two lonely figures over him and knew that Satan was near.

Eight months later Sidney was again in Berlin, a fellow at the American Cultural – Historical Society. That was unusual too, an Italian art scholar here, but the Society strove for variety. And he was a celebrity, good for Society public relations. The joy of it was that he was relatively free of obligations or Society geared projects. And Montereali was here where now in Sidney’s mind Masaccio seemed to survive.

His book – exposé had taken shape in a manner he could never have dreamed. Before Montereali. Before Berlin. Crazy subject for a Jewish scholar, he knew. Masaccio and all his Christ’s! But they were after all so man – like … their human dimension. And their message was freedom. Free of inhibitions! And on another level, and despite the skepticism of the academic community, he congratulated himself that he was resolving a mystery that had resisted over a half millennium of investigations.

“How is it possible that a computer can just disappear?” Sidney said to his wife Isabel before he’d even closed the door of their apartment on the second floor of the villa. He had just returned from another fruitless trip to Rome.

“Such things happen,” Isabel said and clapped him on the shoulder fraternally.

“ But I can hardly believe that anyone in the Society, the cream of the American intelligentsia, would steal my old laptop. Everything was in it … all my research of the last year … the discovery of a lifetime.”

“Nonetheless it’s gone, lover boy. I waited a day before calling you while police and the admin people checked. An inside job! Police say it wasn’t the employees. Sidney, it wasn’t the computer the thief wanted … but what was in it. And we know very well who would most like to get his hands on it, eh, sweetheart.”

Isabel reached up to him, caressed his long blond hair, smiled her most optimistic smile and put her head against his narrow chest.

Sidney instead threw up his hands in desperation. He felt like crying. “And my talk for tomorrow evening is in that computer too! I don’t know how much I can reconstruct from my notes and my excited brain.”

“The talk is one thing, you can fake it a bit. But the book is something else!”

Sidney freed himself from her protective embrace, walked out onto the terrace and stared down toward the Wannsee where he walked each evening. ‘The same old story,’ he thought. ‘Mornings so full of ardour and confidence, withering away as evening approaches.’ In this moment dependent on a computer! He, Sidney Sonnino, a leader fearful of his own authority! Therefore his walks in the darkness provoked such obsessive and interminable interior monologues.

A thin layer of snow lay on the terrace and on the gardens reaching to lakeside. Low walls rising mysteriously out of the snow marked the outline of a former swimming pool. Giant oaks on the east side of the gardens loomed like nocturnal mushrooms. Abandoned boats in the ice filled basin bobbed and rocked frenetically against the docks as if trying to escape the clutches of the winter storm blowing across the lake. The ducks had vanished. The tops of the seven maple trees along the lakefront were silhouetted against the dark waters like seven lopped heads. The ferryboat headed toward Kladow on the north shore darted in and out among the green and white breakers rolling across the lake. Closer to the shore seagulls flapped and squawked as if in anger.

Mesmerized by the human silence that hung like defeat before the crashing violence of nature, he forgot momentarily the gravity of his situation … until he turned back toward the living room and met Isabel’s woebegone eyes.

“Mark Schweer!” he said, returning into the living room. He pronounced that name for her sake and in an attempt to erase the Weltschmerz he felt in his face.

“Of course,” she said. “That Nazi swine! Despicable Prussian! No wonder he’s stiff as a poker when he sees us. But I don’t know who’s worse, he or his conniving wife. She would kill her grandmother to further his career.”

“Certainly he’s gifted in his way but I’ve never trusted him,” Sidney said.

“Yes, but you’re a Jew and he’s still a fucking Nazi.”

“Now, Isabel, we don’t know that for sure.” Sidney, but nature introvert and timid, felt uncomfortable with his wife’s intransigence. Once right was established she never had doubts. But how do you really know what’s in another’s mind?

“Come off that fair – mindedness stuff, Sidney! You know very well what he is.”

“In a way you’re right. Alex says he’s full of complexes because of his father. He really was a Nazi, you know. I don’t think Mark knows who he is. Maybe that’s why he’s here … not unlike me.”

“Oh, God! And we had to come to Berlin for that.”

That evening the fellows were gathered informally with wives and children in the dining room. Tensions were rife. Sidney and Isabel carried on conversations with the others at their table, trying not to look at art history Professor Mark Schweer and his wife, Hannah, with their two children at a table in the rear. But the Sonnino’s accusing eyes were continually drawn to them. From time to time the outrageously handsome Schweer or his arrogant Teutonic wife gazed vaguely in their direction too, fleeting glances that as a rule wandered slowly past them and out the terrace windows facing the Wannsee.

“Listen, Sidney, how is possible that you just left your computer in your study unprotected?” whispered the philosophy professor from Cornell, sitting next to them.

“Alex, I don’t know how I could I be so foolish! But who would imagine a robbery here!”

“You know the maids go in to clean everyday. Why practically anyone could get in.”

“That blond she – devil Hannah too,” Isabel said. “She only looks like an angel … I wonder how they stand each other.”

“But why?” Alex insisted. “How would your computer help Schweer?”

“Help him!” Sidney exclaimed, staring across the several tables of diners to the group of whispering heads turned toward Mark Schweer. The Professor, as people called him, was leaning back in his chair, his mustache thick and flamboyant, his rich hair combed backwards. “I should say! I can show that his idol, that falsifier and exploiter, Masolino da Panicale, murdered Masaccio! It ruins Mark’s life work, that’s all. It would destroy his classic Masolino A Life. It’s a little like killing Mark Schweer too.”

“The double – dealing son of a bitch!” Isabel insisted. “He looks so pleased with himself … with his perpetual … his perpetual ecstacy. He thinks it purifies him, the creep!”

“Look at this place,” Sidney said, an almost amused expression in his eyes at his wife’s rage; she saw Mark with such different eyes. “Looks like the United Nations voting on another war.”

A palpable atmosphere of intrigue had spread across the dining room. An iron curtain seemed to separate the four long parallel tables. “Schweer – Masolino war supporters back there,” he added. “Sonnino – Masaccio peace champions here.”

“Life!” Isabel said.

“You always get to the point before anyone else,” Sidney said, turning a look of admiration on his wife. One thing about her, he thought, she was above all loyal.

“It’s peculiar that Schweer seems to have so many supporters here,” Alex said. “Why? After all it’s so easy to read him. He’s such a fake.”

“Why?” Sidney said, a faraway look in his eyes. “Alex, you should know that’s just the way people are. Most people need and like the Court.”

On the S – Bahn to Potsdam the next morning Sidney told Isabel a little about the painting they were going to visit at Sans Souci Castle. “Remember that Rubens modelled his Hercules and the Lion of Nemea on many paintings of the same theme, on Raffaello’s Sansone che spezza la mascella al leone, and on a bas relief in Villa Medici in Rome, and especially on the Giulio Romano frescoes in Palazzo del Te in Mantua. That’s why they called Rubens the Italian back then. And those models of course mean also the influence of his beloved Leonardo da Vinci … and so back to you know who!”

“To Masaccio!”

“Naturally.”

“And that will be your point in your talk tonight?”

“Yes. And on models.”

“Models?”

“I will make the point that we all model ourselves on someone. Most people need heroes. But some are heroes. That was the basic discrepancy between Masaccio and his master, Masolino. The master knew he was an imitator.”

Their faces were pressed against the train windows as they passed through booming Babelsberg, the movie town. They hoped for a glimpse of a film studio or just the street name, Marlene – Dietrich – Allee. They saw nothing but colorless residential areas and row houses and bars and restaurants.

“But also,” Sidney said, “I will stress the red line running from Masaccio via Paolo Veronese and Michelangelo to Rubens. And thus straight to north European art.”

“Everything seems to lead back to him! Is it a boon or a detriment to live life with such a passion as yours?”

The train came to stop at the Potsdamer Bahnhof. “Do you think I chose it?” Sidney said sadly as he stood up and took her arm.

The lecture room was packed. The fellows and their wives, Society sponsors from various European countries, Berlin dignitaries and several German art historians Sidney had personally invited.

A ripple of restrained applause greeted Sidney when he stepped behind the speaker’s lectern— from the back rows too the applause was ambivalent, as if uncertain as to whether he was aggressor or victim. Schweer’s friends occupying the front rows like Maginot Line trenches held scraps of paper ostentatiously ready for drawing pictures and playing word games. Chairs scraped, throats cleared, coughs were barely suppressed.

Sidney stared down at Mark Schweer and beautiful smirking Hannah in the middle of the first row. He read taunts and sneers in their handsome faces. Old ‘facts are facts’ Schweer! he thought. Pedant! Pedestrian! His famous pronouncements preceded by “in my humble opinion” or his theatrical German “meiner Ansicht nach” qualified here by a “virtually,” there by an “en effet.” It must work well on his students.

Sidney straightened his crooked tie and grinned at Isabel in the second row behind the Schweer’s. He shuffled the pages of his hastily prepared lecture, cleared his throat … and on the spur of the moment decided to extemporize:

“This morning my wife and I saw a famous Rubens painting. Rubens again provoked in me the question of the choice of freedom that each of us makes, either consciously or more often than not subconsciously. I mean the difference between being and seeming. It is the age – old question of life or theatre. Of truth and authenticity or imitation and fakery.

“My research into the life and work of Masaccio has convinced me of his dedication to truth and the liberation of man from religious superstition and social encroachment. Rubens on the other hand, for me, though technically impeccable and one of our greatest artists, when all is said and done, remains the imitator. He is the man of the Court, masterfully reproducing beauty, reproducing fashion and the theatrical of life. Yet each of his greatest paintings inevitably evoke in me merely the past—another artist, another period.”

Mark Schweer had begun squirming in his chair and looking around the room as if ready to stand up and leave. Hannah was pulling at his arm.

“Instead of looking at a work of art and really seeing it,” Sidney continued, “most people tend to accept the explanations of specialists as to what a work of art is. Great paintings of course have more than one view. Interpretations are open to interpretation … naturally including my own. Truth is forever elusive. However, one thing is certain—true truth does not live in imitation.

“Both Rubens and Masaccio count among the greatest artists.

“Yet, in my opinion, Rubens is theater, imitation, counterfeit.

“Masaccio, on the other hand, is life, truth, authenticity.”

A single chair scraped. Sidney paused. Schweer had twisted in his seat, his head turned to one side, and thrown up a hand in front of his face as if to shield himself from the assault of such blasphemy.

Pleased he had achieved his objective, Sidney grinned and continued:

“The question today is still the same as when Masaccio was upsetting accepted truths established once and for all by Church dogma—what will the imitators not do in order to arrive? They will lie, cheat and steal as man has done since Cain and Abel. They …”

At those last words a current of mutterings and shuffling of feet and scraping of chairs passed through the hall. All the fellows understood the charge. Hannah Schweer squealed. Mark had half risen from his seat when from the back of the room a Society secretary cleared her throat and, jumping up and down, shouted in a whisper ‘Herr Sonnino! Herr Sonnino!’ She held up Sidney’s laptop like a trophy, as if to say he could now begin his real lecture.

“It was in the bath house!” she said.

“Hurrah! Hurrah!” Isabel shouted from behind Schweer’s shoulder.

“Thank you,” Sidney said with a slight bow to the audience. “Thank you all.” While many of the fellows applauded, he walked briskly to the rear and took his computer from the young lady’s hands still quivering from excitement.

“Where were you really going with that life or theater analogy?” Isabel asked later that evening as they half watched a familiar old American movie dubbed in German and tried to understand some of the lines. Sidney maintained it was their difficult language, almost a secret language, that made Germans so different. Their language seemed like a mask! You listen to them speak and they seem to be masking their real selves. What was it they were hiding, he wondered?

“Oh, I had in mind the juxtapositions of life. For what kind of accord could have linked Masaccio and Masolino? Masolino who relied on divine inspiration while Masaccio had already turned his back on the angles as a youth. Masaccio’s rejection of the irrational, his jettisoning of description in favor of narration—oh yes, Isabel, that is his art! His rejection of Masolino’s theatricality echoing an invisible god. His subjects leading a heroic existence, aware of their right to know. His rejection of the inauthenticity of the Court in favor of the potential authenticity in the real life of the workers’ district of Florence. I had in mind also a burgeoning Berlin in comparison to Catholic theatrical Court – like Munich. Or market – oriented Milan as compared to political Rome. New York rather than Washington … that kind of thing.”

Toward the end of another CNN pro – war economic – military analysis, Isabel yawned loudly, her skirt up to her hips, and said provocatively, “Well, lover, aren’t you going to take your usual walk to the lake tonight?”

“I don’t think so,” he said leering at her legs. “I feel like I’m coming down with a cold.”

“Hypochondriac!”

“My throat was raw even during my talk.”

“Liar lover! You were only up there seven minutes!”

“Too long for the Schweers! You should’ve seen the look on their faces when Frau Schmiedinger announced her find … you’ve got great legs, you know!”

“I was right behind Hannah and heard what she said into his ear—‘I’ll kill that bastard,’ she said. “You, that is. And I really believe she would do it.”

“But why did the thief just hide it down there in the bathhouse instead of destroying it or scrambling it. I can hardly believe everything’s intact.”

“Maybe he—or she—planned on copying the good stuff!” Isabel sat down at the Bösendorfer and ran her hands passionately across the keyboard. “What a satisfying feeling,” she said.

“Maybe they did already,” Sidney said, caressing her hair. “You’ve got great hands, you know.”

“What’s this euphemistic ‘the thief’ or ‘he or she’ stuff mean?” Isabel said. “We both know we’re talking about none other than that Nazi anti – Semite, Professor Mark Schweer and Frau Doctor Professor Hannah!”

“Well, Sweetheart, the computer is intact, Masaccio is safe, and we’re cozy cozy in our nest looking over the lake. What do you say we retire to our boudoir and consider more interesting endeavors.”

“I’m with you, Lover. A much more engaging idea than nocturnal walks along the Havel.”

While the Sonnino’s frolicked festively in the king sized bed, on the opposite side of the sprawling villa Mark Schweer stared out the windows of his apartment. The Wannsee night was cold and clear. The stars seemed more distant than in the skies over America. It was a strange feeling being back in the Berlin of his parents and grandparents. He liked to stroll along the Kurfürstendamm but it somehow wasn’t the same as when he was a student here and they all called it the Ku – damm. Today he continued to avoid former East Berlin, he wasn’t sure why. He disliked Unter den Linden; for him it still smacked of the East. He had no use for Mitte. Again and again he would stand on the corner of Fasanenstrasse or sit in the terrace café of the Kempinski, but former West Berlin also seemed pointless. He didn’t feel the spirit of before, when the Wall was there. Nor were the people the same. Where was everyone, he wondered? It wasn’t like that in the Berlin of his own early years when he was still painting. He smiled at the image of himself standing before his easel in the apartment in Dahlem. Yet, though he had felt some underlying affinity in those years—the certainties of the firm ideology of the bastion Berlin—even then he was a stranger to that time and that place. He thought it must be atavistic. After all, his father hadn’t been able to swallow all that liberal shit American intellectuals spouted in post – war Berlin. Yet Mark had never digested all the Nazi shit his father preached either—right up to his death his father had regretted that Americans had not joined up with Germans to squash the USSR, right then, in 1944. He felt no less detached from his father than from the liberal set of Sonnino. ‘We’re a detached generation,’ he thought. ‘We just don’t belong.’

Speculatively he touched the roll of fat around his waist, frowned, and again wondered where Hannah was and what she was up to. Despite his usual matinal vow to the contrary he had again eaten and drunk too much at the dinner offered by the Society in honor of the evening’s speaker—his enemy, Sidney Sonnino. Still, broken promises had become a way of life. But no, he wasn’t drunk. In fact, that was the problem—he found it increasingly hard to get drunk. But he felt sluggish and dull – witted. It had come on him while he tried to concentrate on what that pompous asshole Sonnino was saying in that truncated speech. He’d been delighted at the interruption … ‘but the nerve of Sonnino, just to bow and walk away like that. But he did it with style and aplomb,’ he admitted. ‘Almost in triumph. Not that I’m in the least anti – Semitic—no, no, despite my Dad, I’m not—but that’s just the way these Jewish intellectuals are! And why isn’t Sonnino in Italy anyway if he’s so enamored of that Che Guevara Masaccio? What’s he doing up here?’

Yet, yet, Hannah had been stupid to stash the laptop in the bathhouse before he even had a chance to look it over … look it over, and maybe copy out extracts.

The lake down below was silent, a dark invitation. After the brilliant sunsets, the night, the stars, the north, the lamps along the waterfront, stirred something in his Germanic soul. It was a mystery, the things that once were and are no more!

In his wife’s continuing absence Mark Schweer decided to take a walk. It might do some good. Yes, he would begin a nightly walk after dinner. A constitutional! Thickening waistlines were the dangers of his sedentary profession. That, and not publishing. That was another thing, all this obligatory publishing. The problem was ideas! That had always been the problem. Better if he’d stuck to his painting. But the problem there was always the same—what to paint … at least something people would buy. Now where did Sonnino get all his ideas? Down there, right down there at the lake maybe. In the dark? In the cold and the wind? And he also had this thing of staring out windows! What’s he looking for? Always worrying about the social in everything! Social here, social there. What could he want anyway, a classless society? Fucking Communist! Jews all seem to be Communists. His father always said most Communists were Jews. As if a painter had to project social ideas into art! And all that ugly chiaroscuro he loved! What is it Sonnino wrote about Masaccio? ‘He painted the new man!’

‘New man, my ass!’ As if Masolino exploited him, when it was that brat Masaccio who hung onto his master’s coattails to arrive.

‘Not that anyone really cares. But Sonnino seems dedicated to destroying me. He talks about the social but it’s really just pure envy … and ambition too—he wants to make a name for himself by undermining me. All his talk about disenchantment with the world and about the artist’s social role. His is a mad design! That’s it. First his social essays. Now a book. Still his ambition is understandable. And it’s not the end of the world. I have a good job, I’m respected, I get the recognition and the rewards. The crazy thing is how Hannah takes it on herself to stop him. Well, she’s right too … somebody ought to teach that self – righteous bastard a lesson. But Hannah! Woman of violent solutions! You’d think she’d been out there in the mock war maneuvers in the woods with me! A lady of action, she is! Now how did I ever get mixed up in all that military crap? My Dad’s influence again. But stealing a Society fellow’s computer! She has to be crazy.’

In the cellar, petite Hannah Schweer had rummaged around in the storage rooms until she found what she was looking for. Not a soul was in sight. No one ever came here at night. She lifted the short axe in one hand and swung it in a cross motion, a kind of arc diagonally from right to left. She grinned in satisfaction. Yes, she could handle it easily. A good sock on the head with this and that upstart Sonnino would spend the next semester in the hospital. Might get some sense into his head. She had seen just enough on the laptop to know what he was up to—if he revealed that Mark’s favorite artist was a murderer, then her husband’s book on Masolino would be meaningless. His work of the last five years would go up in smoke.

‘Mark talks a good game,’ she told herself, ‘but when it comes down to the act he’s a coward.’ It was infuriating that he didn’t raise an arm to defend himself. There was a time to fight … the Bible said so.

Again Hannah looked at her watch. It was nearly time for Sonnino’s evening walk in the back gardens. Night after night, while Mark watched some TV show in that mysterious language that she couldn’t understand, she had observed Sidney from her window upstairs. Each night at 11 o’clock he repeated the same routine. From the rear terrace his tall figure dressed in black topcoat and black scarf and cap meandered down the walkway to the former swimming pool that seemed to fascinate him each time again. Then on to the boat basin where he stood motionless as if checking that all the boats were there. And no matter how cold it was he would sit a few minutes on the same bench facing the lake.

She always shivered observing his silhouette, under the lamp only a ghostly outline against the dark water. When he then turned back up the pathway on the opposite side of the park, he invariably stopped near the bathhouse as if reading the signs and instructions for use.

Tonight the trees lining the high wall cast nocturnal shadows over the bathhouse so that the dark was total. She would wait for him there.

Professor Schweer lifted his glass and drank off the weinbrand he had been resisting. He looked toward the window, shrugged, poured himself another, and drank it off without a second thought. So much for that! He put on his topcoat and black cap and yellow scarf, walked down the hall, and took the elevator to the cellar.

From the rear terrace his eyes swept over the park and stopped on the statue about half way down the slope toward the lake. He knew it well—Georg Kolbe’s Verkündigung of 1937. The beautiful nude Aryan woman was fitting. But, he wondered, an Annunciation? In those years? He noted the bunker next to the kitchen and again recalled that the villa once belonged to a prominent Nazi. Lucky bastard! Not like his worker father who’d had to scrape and bow just to survive. No wonder he became a Nazi! But this bigwig just stashed away the whole family when the air raids came.

‘But didn’t they ever accept that it was all about to end? What could they’ve been thinking about when bombs were falling all over the place? Carpet bombing Hamburg and Köln and Düsseldorf and Essen and Frankfurt and München and Nürnberg and they thought Berlin would be spared. That some magic weapon would save them. Well, if they’d developed the bomb first, everything would’ve changed. Those times are over … but sometimes I wonder what would’ve happened otherwise.’

The bare limbs of the oaks were astir when he stopped at the bathhouse and read the words on the two doors—Damen and Herren. Why the separation while it was raining bombs? Was there a rush on the bathhouse? In these months he’d never seen anyone even near it. Bathhouse had a bad ring.

He placed both hands on the sill of the only window, lifted himself on his toes, and peered in.

Blackness.

As silent as an Apache, Hannah in the same moment slipped from around the corner of the bathhouse, her weapon poised. Despite her internal agitation and adrenalin – fired strength, the axe now weighed heavy in her hand. She glanced at it again. Was it the same axe?

But then there was the enemy, Sidney Sonnino. His face was pressed against the panes. What did he expect to see inside? she thought as her mind wandered into distant regions. His future? Paradise?

She lifted the axe from her shoulder and paused briefly, glancing at it again, surprised that Sonnino didn’t sense her behind him.

‘I’ll show you … Masaccio … that’s a laugh!’

As she swung her arm, the axe weighed like leaden dreams. Her hand twisted. In a flash she realized she was missing her mark. Instinct? Sixth sense? The axe seemed to take its own irresistible course. Not the blunt side, but the blade came down. And not on his head, but toward his shoulder.

The enemy twisted toward her, and yelled in a familiar tone “Hey!” before he fell against the bathhouse door and slipped slowly to the ground.

Hannah shrank backwards and threw the axe away from her. As she turned to run to the house, she saw in a reflection from a distant lamp along the lakefront a shimmering of color at her feet. She leaned over the black form and saw in horror his yellow scarf. She knew it was yellow. It had to be yellow.

She stooped and ran her hand over the head and neck. Something gooey was spreading.

The next morning Sidney hummed to himself as he went downstairs for the newspapers, and coffee for Isabel. After his strenuous evening he had slept like a log. The elevator was so unusually busy, up and down between the admin offices upstairs and the cellar, that he gave up and walked down to the Erdgeschoss.

On the ground floor a uniformed cop and a tall thin man in a black topcoat stepped out of the elevator. Curious, Sidney opened the front door and stepped onto the porch. Two green police cars and several official – looking black Mercedes were parked in front. Yes, the American Society villa was a natural terrorist target but he’d never seen more than the two men in the mysterious green van near the gate with its motor constantly running for heat. Policemen were now nosing around the grounds and disappearing down the side toward the rear gardens.

A gelid gust of wind forced him back inside.

He knocked on the closed door of the receptionist’s office in the hall to ask what was happening. No answer. Strange, he thought, picking up from a table the Tagesspiegel and the TAZ , she was always there.

In the dining room three fellows huddled at the rear table fell silent when he walked in. Sidney shrugged. Still trying to get right the theme he loved from Bohème, he filled a mug with espresso for Isabel. That woman would sleep forever without it.

“What’s going on out there?” he then asked the others over his shoulder and pressed the espresso button again.

“What’s going on?” a voice echoed his words.

“They took Mark to the hospital late last night.”

“Hospital?” Sidney spun around, spilling coffee on his hand, and yelled in pain. He sat down uneasily at the far end of the table.

“Hannah found him at midnight in the back gardens,” one said. “Someone clubbed him … nearly chopped his arm off.”

“He could have frozen to death!” said another.

“Why would anyone club a fellow here? Do they suspect terrorists?”

“No, no terrorism … an inside job, police believe. Crazy, but Hannah claimed it was Masaccio.”

Sidney sat there at the end of table, stunned and puzzled. A fellow attacked and nearly dead! And Mark of all people. But what could Hannah mean, Masaccio did it? An apocryphal kind of statement, he thought, except she had confused the characters. But Masaccio? She must mean me, he thought, bewildered by his conclusion.

What was it that old Montereali said about Berlin? A crossroads! The future! Something to the effect that it was a place many have died for!

![]()

Our Senior Editor based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

Our Senior Editor based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

=SUBSCRIBE TODAY! NOTHING TO LOSE, EVERYTHING TO GAIN.=

free • safe • invaluable

[email-subscribers namefield=”YES” desc=”” group=”Public”]