=By= Allie Yee

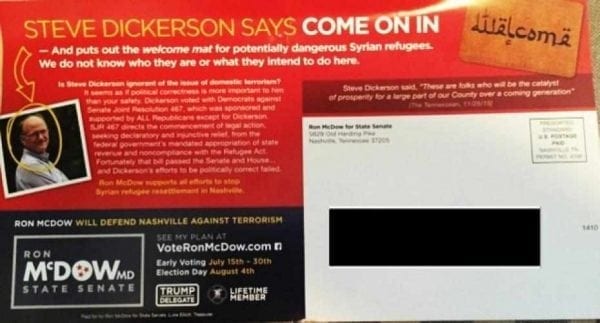

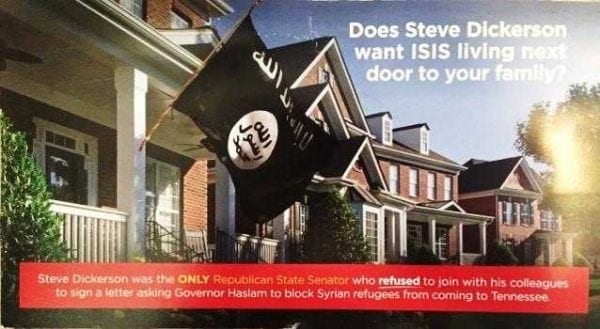

Anti-refugee sentiment has become a key issue in Southern state and local elections — including in a state Senate primary race in Nashville, Tennessee, where this attack ad targeted incumbent state Sen. Steve Dickerson. (Mailer image courtesy of the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition.)

![]() There are two parts to this report and both are in this post. The links below are The Greanville Post navigational links.

There are two parts to this report and both are in this post. The links below are The Greanville Post navigational links.

Part I: Refugees become a flash point in elections across the South

Part II: Refugees stand up to anti-immigrant sentiment in the South

Part I: Refugees become a flash point in elections across the South

Refugees have drawn big cheers at the 2016 Rio Olympics this summer, competing as part of the first-ever Refugee Olympic Team. Comprised of athletes who’ve fled war-ravaged homelands in Africa and the Middle East, the 10-member team was created as a symbol of hope for refugees worldwide and to bring attention to the ongoing global refugee crisis.But in the U.S. South, the presence of refugees — and their potential future arrival — have been far more controversial, and the hot-button issue has found its way into this year’s state and local elections.

The tone of the national debate over refugees was set late last year when, after the November terrorist attacks in Paris, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump called for a ban on Muslims entering the U.S. But while Trump’s rhetoric was particularly extreme, his were far from the only anti-Muslim and anti-refugee statements made by politicians.

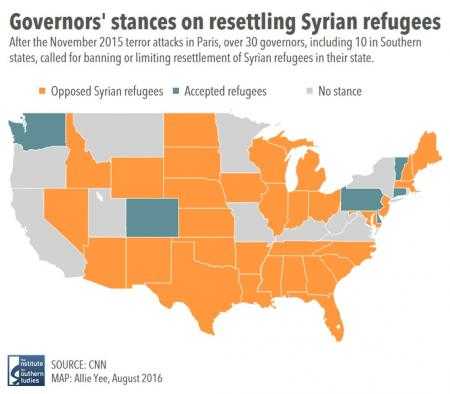

Even as local agencies and officials urged openness, over 30 governors called on federal authorities to stop resettling refugees in their state. Among them were the governors of 10 of the 13 Southern states.

“[Anti-refugee sentiment] was really fueled by the election rhetoric at the federal level,” said Stephanie Teatro, co-executive director of the Tennessee Immigrants and Refugee Rights Coalition (TIRRC). “And we absolutely saw the trickle-down.”

Some critics charged that these statements against refugees, particularly those from Syria, were an attempt to play on people’s fears in order to score points in an election year. For example, when North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory (R) called for a stop to resettling Syrian refugees in his state, a representative of a refugee assistance agency noted the political nature of the governor’s move.

“What we’re fighting is an election cycle,” Andrew Timbie, then with World Relief’s High Point, North Carolina, office, said at the time. He noted that raising concerns about refugees and resisting President Obama’s refugee resettlement efforts would resonate with certain voters in the state.

This fall McCrory is facing off against state Attorney General Roy Cooper (D) in one of the nation’s tightest gubernatorial races. Back in November, the McCrory campaign used his statement about banning Syrian refugees as a fundraising hook on Facebook, with a post that read “NO SYRIAN REFUGEES” and linked to his campaign’s contribution page. Cooper also put out a statement asking to “pause” Syrian refugee resettlement.

It’s not just governors and would-be governors who are using the refugee crisis for political advantage. State legislators in Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina and elsewhere have introduced legislation to ban new refugee arrivals to their states or to make resettlement more difficult. Texas and Alabama went so far as to sue the federal government to block refugees, although both of those lawsuits have been dismissed.

And Tennessee lawmakers passed a resolution earlier this year directing the state to sue the federal government over refugee resettlement under the 10th Amendment, which limits federal powers. The resolution passed despite reservations from Gov. Bill Haslam (R), who did not sign it, and the refusal of state Attorney General Herbert Slatery (R) to represent the state in any such lawsuit.

“There were a handful of legislators who saw this as a winning political issue,” Teatro from TIRRC said. “[They thought] that they could really run on and build a reputation on being tough on refugees.”

No lawsuit has been filed yet. Tennessee legislators are considering hiring an outside law firm to represent the state.

Fertile ground for backlash

The political backlash against refugees comes at a time when the South — a region with historically low rates of immigration — has been experiencing dramatic growth in foreign-born newcomers, including refugees.

Southern states like Tennessee, South Carolina and Alabama have had some of the fastest rates of growth nationally among their foreign-born populations. And while immigrants make up only a small share of most Southern states’ population — and refugees an even smaller share — the arrival of new languages, complexions, cultures and religions has elicited reactions from local communities ranging from wariness to outright hostility and even violence.

Southern states like Tennessee, South Carolina and Alabama have had some of the fastest rates of growth nationally among their foreign-born populations. And while immigrants make up only a small share of most Southern states’ population — and refugees an even smaller share — the arrival of new languages, complexions, cultures and religions has elicited reactions from local communities ranging from wariness to outright hostility and even violence.

The anti-refugee reaction is intertwined with the rise of anti-Islamic sentiment in the region. A report published last year by TIRRC addressed this in Tennessee:

In this context of generalized anxiety and backlash against newcomers, Islamophobia was never far from the surface. An estimated 48% of refugees resettled in Tennessee in 2013 were from majority Muslim countries, while only 1% of US-born Tennesseans identify as Muslim.

Syrian refugees, who have been the focal point of the anti-refugee backlash in the past year, have been increasing in numbers in Southern states recently. But even so, they make up only a small share of all the refugees coming to the region, many of whom are coming from other conflict-torn countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia and Bhutan.

A sign of hope in Tennessee

A debate over refugees is also taking place on the local level across the South, with responses ranging widely from place to place.

Some local communities in the region have been extremely hostile to refugees. The TIRRC report chronicles how backlash in Tennessee cities including Nashville, Columbia, Shelbyville and Murfreesboro stoked anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiment across the state. Incidents like the 2010 arson at a mosque in Murfreesboro garnered widespread media attention and established the state’s reputation as unwelcoming of newcomers.

Since the Paris terror attacks, at least two counties in North Carolina — Craven County in the east and Henderson County in the west — have passed resolutions banning the resettlement of refugees there. These moves are largely symbolic since localities don’t have the authority to enforce a ban, and the commissioners passing them have acknowledged as much. But one Henderson County commissioner said the resolution “sends a message to state and federal representatives where Henderson County stands.”

Many of the Southern communities most hostile to refugees have had few resettled there. But in communities that have become resettlement hubs, the sentiment is often very different.

“Some of the anti-refugee voices are coming from places with few refugees,” Teatro noted. “In cities and communities where refugees are actually resettled, they are welcomed and the program is defended.”

“Some of the anti-refugee voices are coming from places with few refugees,” Teatro noted. “In cities and communities where refugees are actually resettled, they are welcomed and the program is defended.”

Nashville, Tennessee, where TIRRC is based, is home to 75 percent of the refugees who have resettled in the state. The fast-growing city has been proactive in welcoming both immigrants and refugees.

Teatro was encouraged by Nashville voters’ rejection just last week of a candidate who sent a campaign mailer that attempted to stoke anti-refugee fears.

In the GOP primary for the state Senate’s District 20 seat, challenger Ron McDow attacked incumbent Steve Dickerson for being the only state Senate Republican not to vote for the resolution directing the state to sue over refugee resettlement.

McDow distributed a campaign mailer in July showing an image of an ISIS flag flying in a neighborhood, with the words, “Does Steve Dickerson want ISIS living next door to your family?” On the other side, the mailer said, “Steve Dickerson says come on in — and puts out the welcome mat for potential dangerous Syrian refugees.”

In response to the ads, Dickerson stood by his vote, saying, “The people who we are trying to welcome into the country are people who are literally in fear of their lives … This [ad] also misrepresents the refugee community at-large by painting them with this brush.”

In Tennessee’s Aug. 4 primary election, Dickerson won handily with 60 percent of the vote in his district. For Teatro, it was a hopeful sign.

“We know legislators will continue to play on the worst sentiments of Tennesseans,” Teatro said. “But we’re also optimistic that [Tennesseans] voted against that rhetoric.”

[Top of Post]Part II: Refugees stand up to anti-immigrant sentiment in the South

[Top of post]

For Ahmed Osman, coming to the U.S. was like coming to a new world.Originally from Somalia where civil war has displaced hundreds of thousands of people, Osman arrived in snow-covered Minneapolis in March 2009.

“It [was] a totally different country in every aspect of life,” Osman said.

Osman moved to Nashville, Tennessee, later that year, coming to a Southern city with a growing Somali refugee community where he knew a few people. While he could speak English, finding a job and fitting in to the community in Nashville was still a challenge. It took him six months to find a job, he said.

Beyond the struggles of daily life, Osman, who is a Muslim immigrant, had come to a region where leaders and communities have become increasingly hostile to people like him. Since Osman arrived in Tennessee, lawmakers there and in other states across the South have introduced legislation targeting Islamic Sharia law, establishing English-only mandates and creating other barriers for immigrants.

After the Paris terror attacks last November, antagonism towards refugees, particularly those from majority Muslim countries, flared. While Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump’s anti-refugee rhetoric made headlines, Southern politicians have also stoked fears about refugees in the region.

That backlash has in turn motivated refugees like Osman to speak out and — for those like him who are naturalized citizens — to vote in the upcoming election.

“I hear a lot of comments from people [in my community] saying if Donald Trump is elected, he’ll send us back,” Osman said. “There is a fear created by his campaign.

“That’s why I’m focusing and everyone in my community is focusing this year,” he said.

Coming to the South

Each year since 2012, roughly 20,000 refugees have been resettled in the 13 Southern states, according a Facing South analysis of Office of Refugee Resettlement data. They make up about 30 percent of the new refugee arrivals to the country each year.

While concerns about those fleeing war-torn Syria have been the focus recently, refugees from that country have made up only about 1 percent of recent arrivals in the South between 2012 and 2015. Almost half have come from Burma and Iraq, with significant numbers from Bhutan, Cuba, Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Before coming to the U.S., refugees go through a thorough vetting process that can take years and involves several international and U.S. federal agencies. The federal government partners with local agencies, including faith-based organizations like Catholic Charities of Tennessee and Church World Services in North Carolina, to resettle refugees in local communities.

Each year since 2012, roughly 20,000 refugees have been resettled in the 13 Southern states.

When Aline Ruhashya arrived in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1998, she felt a mix of emotions. Originally from Rwanda, she fled the 1994 genocide in her home country, traveling to Congo, Kenya and Senegal before coming to the U.S. Initially, there was a “honeymoon phase,” she said, when she was so excited to arrive and for all the promise of opportunity.

But reality quickly set in. The apartment she lived in with her relatives lacked some basic needs, like pots to cook in. A teenager when she arrived, she struggled to understand her teachers and fit in at school. And with only three months of support from the resettlement agency, she worried about how her family would support itself when that time was up.

“Those things kind of make you start wondering, am I going to be OK?” Ruhashya said.

But there were also those who extended a helping hand to Ruhashya and her family, and this was another highlight of her experience coming to the U.S. It wasn’t only the people with the refugee agency but also neighbors and teachers who helped her adjust to life in her new country.

In 2005, Ruhashya became a U.S. citizen, as refugees are eligible to do after living in the country for five years, fulfilling her dream of becoming an American. The naturalization ceremony was an emotional experience for her.

“Seeing all these people from different walks of life, different skin colors, different nationalities, becoming American citizens together,” Ruhashya explained, “It’s just like the foundation of this country.”

Overcoming the myriad of challenges involved in coming to a new country and building a new life, refugees and other immigrants contribute in important ways to their communities. A recent study by the Partnership for a New American Economy found that in North Carolina alone immigrants earned more than $19 billion in income and paid more than $5 billion in taxes. In 2014, they generated $972 million in business income and employed 120,800 people.

But recent rhetoric has increasingly cast immigrants and refugees as drains on local economies and threats to safety. These portrayals have been heartbreaking to Ruhashya, who said people don’t understand how hard it is to be a refugee and not have a country that you belong to.

“It’s not just about things like money,” she said. “This person doesn’t need anything. They just need a place to feel safe.”

Lifting up refugee voices

While debate about them rages in politics and the media, refugees themselves have seldom had a voice in the conversation, noted Adamou Mohamed with Church World Services (CWS) in Greensboro.

“Those that are being impacted by all of these negative sentiments that we’ve been seeing in the last year have not been involved much at the table speaking on their own behalf,” said Mohamed, an immigrant from Niger.

Mohamed is a grassroots organizer with CWS who promotes civic engagement among refugees, empowering them to have a greater say in decisions that affect their lives. With Mohamed’s support, refugees have brought their concerns around issues like housing and jobs to their city council members, mayors, state legislators and even federal officials.

Mohamed also encourages civic engagement through citizenship and voting. Becoming a citizen opens up new opportunities in terms of jobs and community involvement. Mohamed also emphasizes to refugees how important their right to vote is.

“It’s not something that was easily granted,” Mohamed said, noting the sacrifices that people have made to ensure people of color and new Americans have the right to vote. Partnering with the local League of Women Voters chapters, CWS helped register over 300 new American voters at naturalization ceremonies in Greensboro last year, Mohamed said.

Meanwhile in Nashville, Ahmed Osman is preparing to vote in his first presidential election. And he’s determined to bring as many people from his community with him as he can.

Seven years after moving to Nashville, Osman has built a life for himself. He knows many more people now, he understands how the system works, and he knows where to turn if he needs help, he said. In 2015, he became a citizen and voted in Nashville’s local elections, which he said was a great experience.

“You come to know that it’s a really nice place,” Osman said about his new hometown. “It’s different today than the first time I was here. More welcoming today than that time.”

Osman has also become a leader and advocate for refugees and immigrants in Nashville, heading the Somali American Association of Nashville and sitting on the mayor’s New American Advisory Council, which addresses immigrants’ and refugees’ concerns with local government.

During the local elections last year, Osman helped organize voter turnout in his community. In Tennessee, nearly 38 percent of the immigrant population — over 114,000 people — were naturalized citizens and eligible to vote in that election, Stephanie Teatro of the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition told local media.

This year, Osman is once again working to get them to the polls.

“This one is personal to every one of us,” Osman said. “Every vote counts, so I’ll try my best.”

[Beginning Part II] [Top of Post]Source (I): Facing South.

Source (II): Facing South.

Note to Commenters

Due to severe hacking attacks in the recent past that brought our site down for up to 11 days with considerable loss of circulation, we exercise extreme caution in the comments we publish, as the comment box has been one of the main arteries to inject malicious code. Because of that comments may not appear immediately, but rest assured that if you are a legitimate commenter your opinion will be published within 24 hours. If your comment fails to appear, and you wish to reach us directly, send us a mail at: editor@greanvillepost.com

We apologize for this inconvenience.

Nauseated by the

Nauseated by the

vile corporate media?

Had enough of their lies, escapism,

omissions and relentless manipulation?

Send a donation to

The Greanville Post–or

But be sure to support YOUR media.

If you don’t, who will?