The Authoritarian Politics of Resentment in Trump’s America

Henry A. Giroux

Henry A. Giroux

Cultural Critic and Public Intellectual

In the face of a putrid and poisonous election cycle that ended with Trump’s presidential victory, liberals and conservatives are quick to argue that Americans have fallen prey to a culture of incivility.

It’s true that in the run-up to the presidential election, Donald Trump strategically showcased incivility in his public appearances as a mark of solidarity with many of his white male followers. However, it is a mistake to lump the racism, bigotry, misogyny and ultra-nationalism that Trump has played upon under an obscuring and euphemistic notion of “incivility.” And it is simultaneously a mistake to delegitimize the anger that oppressed people feel about racism, sexism or class exploitation by categorizing protests over these injuries as merely “incivility.”

Understanding the ramifications of current discourses of incivility will be one key to understanding the results of the presidential election and Trump’s ascension. Clearly, Trump’s embrace of incivility (in addition to his embrace of racism and xenophobia) was a winning strategy, one that not only signaled the degree to which the politics of extremism has moved from the fringes to the center of American politics, but also one that turned politics into a spectacle that fed the rating machines of the mainstream media.

The incivility machine Trump resurrected as tool of resistance against establishment politicians played a major role in gaining him the presidency. Moreover, it turned politics into what Guy Debord once called a “perpetual motion machine” built on fear, anxiety, the war on terror and a full-fledged attack on women, the welfare state and people of color.

Too often during this election season, a discourse of “bad manners” has paraded as insight while working to hide the effects of power, politics, racial injustice and other forms of oppression.

The rhetoric of “incivility” often functions as a conservative ideological tool, working to silence critics by describing them as ill-tempered, rude and uncivilized. Politics, in this sense, shifts from a focus on substance to style — reworking the notion of critical thinking and action through a rulebook of alleged collegiality — which becomes code for the elevated character and manners of the privileged classes. Within this rhetoric, the wealthy, noble and rich are usually deemed to possess admirable character and to engage in civil behavior. At the same time, those who are poor, unemployed, homeless or subject to police violence are not seen as victims of larger political, social and economic forces. On the contrary, their problems are reduced to the depoliticizing discourse of bad character, defined as an individual pathology, and whatever resistance they present is dismissed as rude and uncivil.

As a rich white man who has intentionally embraced an “uncivil” persona, Trump has related to this discourse in unpredictable ways. By claiming he loves the uneducated and appealing to the crudest instincts of the mob, Trump elevates incivility to a performance — a pedagogy of righteous indignation — while removing it as a platform for a substantial political critique. The uncivil persona becomes a threat, a signpost for misdirected anger and a symbol of a mass in need of a savior.

There is more at issue here than ideological obfuscation and a flight from social responsibility on the part of the dominant classes; there is also a language of violence that serves to reproduce existing modes of domination and concentrated relations of power. In this instance, argument, evidence and informed judgment — when they hold power accountable or display a strong response to injustice — are subordinated to the category of unchecked emotions, a politics that embraces rude behavior and a propensity for violence. When deployed in a way that obfuscates the injuries of class, racism, sexism, among other issues, the discourse of incivility reduces politics to the realm of the personal and affective while cancelling out broader political issues such as the underlying conditions that produce anger, the effects of misguided resentment, and a passion that connects the body and mind.

As Benjamin DeMott has pointed out, the discourse of incivility does not raise the crucial question of why American society is tipping over into the dark politics of authoritarianism. On the contrary, the question now asked is “Why has civility declined?” Tied to the privatized orbits of neoliberalism, this is a discourse that trades chiefly in good manners, the virtues of moral uplift and praiseworthy character, all the while refusing to raise private troubles to the level of public issues. The call to civility confuses the relationship between anger and resentment, dismissing both as instances of faulty character and bad manners.

What happens to a democracy when incivility becomes a central organizing principle of politics? What happens to rational debate, culture and justice?

The US has become a country motivated less by anger, which can be used to address the underlying social, political and economic causes of social discontent, than by a galloping culture of individualized resentment, which personalizes problems and tends to seek vengeance on those individuals and groups viewed as a threat to American society. One can argue that the call to civility and condemnation of incivility in public life by the ruling elite no longer registers favorably among individuals and groups who are less interested in mimicking the discourse and manners of the financial elite than in expressing their resentment as they struggle for power, however rude such expressions might appear to the mainstream media and rich and powerful. Rather than an expression of a historic if not dangerous politics of unchecked personal resentment (as seen among many Trump supporters), we are witnessing a legitimate and desperately needed politics of outrage and anger — one that privileges the struggle for justice over an empty call for civility and acceptable manners.

Difference Between Anger and Resentment

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]nger is connected with injustice, while resentment is more about personalized pettiness.

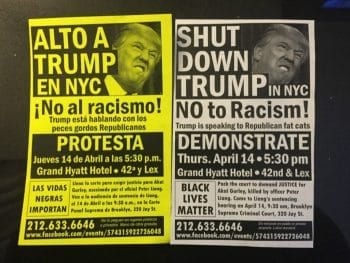

We see elements of crucial anger among the many supporters of Bernie Sanders, as well as the Black Lives Matter movement and the Indigenous-led movement to stop the Dakota Access pipeline. Anger can be a disruption that offers the possibility for critical analysis, calling out the social forces of oppression and violence in which so many current injustices are rooted.

Meanwhile, resentment operates out of a friend/enemy distinction that produces convenient scapegoats. It is the stuff of loathing, racism and spontaneous violence that often gives rise to the spectacle of fear-mongering and implied threats of state repression. In this instance, ideas lose their grip on reality and critical thought falls by the wayside. Echoes of such scapegoat-driven animosity can be heard in Trump’s “rhetorical cluster bombs,” in which he stated publicly that he would like to punch protesters in the face, punish women who have abortions, bring back state-sanctioned torture and, of course, much more. Genuine civic attachments are now cancelled out in the bombast of vileness and shame, which has been made into a national pastime and central to a spectacularized politics.

Reflection no longer challenges a poisonous appeal to commonsense or the signposts of racism, hatred and bigotry. Manufactured ignorance opens the door to an unapologetic culture of bullying and violence aimed at Muslims, immigrants, Blacks and others who do not fit into Trump’s notion of “America.” This is not about the breakdown of civility in US politics or the bemoaned growth of incivility. Throughout its history, US society has been inundated by a toxic, racist ideology that oppresses and marginalizes Black people, Indigenous people and immigrants of color, and particularly since 9/11, has singled out Muslims as targets. It is a market-driven ideology that enshrines greed and self-interest, and a sustained attack on public values and the common good, fueled by the policies of a financial elite — much of it coded by both the Republican and Democratic political establishment.

Trump did not invent these forces; he simply brought them to the surface and made them the centerpiece of his campaign. As anti-democratic pressures mount, the commanding institutions of capital are divorced from matters of politics, ethics and responsibility. The goal of making the world a better place has been replaced by dystopian narratives about how to survive alone in a world whose destruction is just a matter of time. The lure of a better and more just future has given way under the influence of neoliberalism to questions of mere survival. As Zygmunt Bauman has argued in his books Wasted Lives and Consuming Life, entire populations once protected by the social contract are now considered disposable, dispatched to the garbage dump of a society that equates one’s humanity exclusively with their ability to consume.

The not-so-subtle signs of the culture of resentment and cruelty are everywhere, and not just in the proliferation of extremist talking heads, belligerent nihilists and right-wing conspiracy types blathering over the airways, on talk radio, and across various registers of screen culture. Young children, especially those whose parents are being targeted by Trump’s rhetoric, report being bullied more. Hate crimes are on the rise. And state-sanctioned violence is accelerating against Native Americans, Black youth, and others now deemed unworthy and disposable in Trump’s America.

In the mainstream media, the endless and unapologetic proliferation of lies become fodder for higher ratings, informed by a suffocating pastiche of talking heads, all of whom surrender to “the incontestable demands of quiet acceptance,” as Brad Evans and Julien Reid have argued in Truthout. Politics has been reduced to the cult of the spectacle and a performative register of shock, but not merely, as Neal Gabler observes, “in the name of entertainment.” The framing mechanism that drives the mainstream media is a sink-or-swim individualism and a shark-like notion of competition that accentuates and accelerates hostility, insults and the politics of humiliation.

Capitalism’s New Age of Bullying

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]harles Derber and Yale Magrass are right in arguing in Bully Nation that “Capitalism breeds competition and teaches that losers deserve their fate.” But capitalism also does more. It creates an unbridled individualism that embodies a pathological disdain for community, produces a cruel indifference to the social contract, disdains the larger social good, and creates a predatory culture that replaces compassion, sharing and a concern for the other. As the discourse of the common good and compassion withers, the only vocabulary left is that of the bully — one that takes pride in the civic-enervating binary of winners and losers. What has been on full display in the presidential election of 2016 is the merging of the culture of cruelty, the logic of egregious self-interest, a deadly anti-intellectualism, a ravaging unbridled anger, a politics of disposability, and a toxic fear of others. Jessica Lustig captures this organized culture of violence, grudges and resentment in The New York Times Magazine with the following comments:

Grievance is the animating theme of this election and the natural state of at least one of the candidates; Trump is a public figure whose ideology, such as it is, essentially amounts to a politics of the personal grudge. It has drawn to him throngs of disaffected citizens all too glad to reclaim the epithet “deplorable.” But beyond these aggrieved hordes, it can seem at times as if nearly everyone in the country is nursing wounds, cringing over slights and embarrassments, inveighing against enemies and wishing for retribution. Everyone has someone, or something, to resent.

It gets worse. In the age of a bullying internet culture, the trolling community has elected one of its own as president of the United States. Criticizing the pernicious trolling produced by political extremists should not suggest a generalized indictment of the internet and social media, since the latter have also been key tools in pushing back against Trump’s egregiousness. As the apostle of publicity for publicity’s sake, Trump has adopted the practices of reality TV, building his reputation on insults, humiliations, and a discourse of provocation and hate.

According to The New York Times, since announcing his candidacy, Trump used Twitter to insult at least 282 people, places and things. Not only has he honed the technique of trolling, he has also made it a crucial resource in upping the ratings for the mainstream media who, it seems, are insatiable when it comes to covering Trump’s insults. Trump has done more than bring a vicious online harassment culture into the mainstream, he has also legitimated the worst dimensions of politics and brought out of the shadows white nationalists, racist militia types, social media trolls, overt misogynists and a variety of reactionaries who have turned their hate-filled discourse into a weaponized element of political culture. This was all the more obvious when Trump hired Stephen K. Bannon to run his campaign. The former executive chairman of Breitbart News is well known for his extremist views and for his unwavering support for the political alt-right. One of his more controversial headlines on Breitbart read, “Would you rather have feminism or cancer?” He is also considered one of the more prominent advocates of the right-wing trolling mill that is fiercely loyal to Trump. Jared Keller in The Village Voice captures perfectly the essence of Trump’s politics of trolling. He writes:

From the start, the Trump campaign has offered a tsunami of trolling, waves of provocative tweets and soundbites — from “build the wall” to “lock her up” — designed to provoke maximum outrage, followed, when the resulting heat felt a bit too hot, by the classic schoolyard bully’s excuse: that it was merely “sarcasm” or a “joke.” In a way, it is. It’s just a joke with victims and consequences…. Trump’s behavior has normalized trolling as an accepted staple of daily political discourse.

One example of such vitriol was noted by Andrew Marantz’s profile for The New Yorker on Mike Cernovich, a prominent internet troll. He writes:

His political analysis was nearly as crass as his dating advice (“Misogyny Gets You Laid”). In March, he tweeted, “Hillary’s face looks like a melting candle wax. Imagine what her brain looks like.” Next he tweeted a picture of Clinton winking, which he interpreted as “a mild stroke.” By August, he was declaring that she had both a seizure disorder and Parkinson’s disease.

In the age of trolls and the heartless regime of neoliberalism [which the Democrats also unwaveringly supported and the Clintons have been prominent in selling], politics has dissolved into a pit of performative narcissism, testifying to the distinctive power of a corporate-driven culture of consumerism and celebrity marketing, which reconfigures not just political discourse but the nature of power itself. In spite of the large-scale protests against economic injustice that ranged from Madison to Occupy Wall Street, the teacher strikes that have emerged since the 2008 Wall Street collapse, the ensuing political corruption and the consolidation of wealth and power, millions of Americans turned to the politics of resentment.

Amid this turmoil, we cannot let our anger simply become an expression of misdirected resentment. It is time to wake up and repudiate the notion that capitalism and democracy are the same thing. We must use our anger to fight collectively for a politics that refuses to forget the crimes of the past, so it can imagine a different future. Such a struggle is not an act of incivility, but a call to educated hope, civic courage and the need to start organizing.

This totalitarian logic has been reinforced by the strange intersection of celebrity culture, manufactured ignorance and the cult of unbridled emotion, to inhabit a new register of resentment, which as Mark Danner points out in The New York Review of Books, takes “the shape of reality television politics.” Within such an environment, a personalized notion of resentment drives politics while misdirecting rage towards issues that reinforce totalitarian logic. Under such circumstances, the long-standing forces of nativism and demagoguery drive American politics and the truth of events is no longer open to public discussion or informed judgment. All that is left is the empty but dangerous performance of misguided hopes wrapped up in the fog of ignorance, the haze of political and moral indifference, and the looming specter of violence.

The rise of Donald Trump as a corporate-fueled celebrity troll represents the broader contempt for a politics of empathy and compassion. This contempt is the bedrock of a neoliberal formative culture that, as my colleague David Clark once remarked to me, “breeds horrors: the failures of conscience, the wars against thought, and the flirtations with irrationality that lie at the heart of the triumph of every-day aggression, the withering of political life, and the withdrawal into private obsessions.”

The issue is no longer whether politicians, such as Donald Trump, are about to lead us into a new age of authoritarianism and bigotry. Rather, we should be seeking to locate and challenge the forces that have produced these politicians. When individualized resentment and scapegoat-centered violence are normalized, we move closer to a police state and toward an age that forgets the totalitarian impulses that gave us Iraq, state-authorized torture, a carceral state, war crimes, a plundering of the planet, and much more. Trump is only a symptom, not the cause of our troubles. Global capitalism is the monster and Trump is its most dangerous, confused and hateful messenger.

Anger is a double-edged sword and can be transformed into various forms of productive resistance or it can be appropriated and manipulated as a breeding ground for resentment, hate, bigotry and racism. What is clear is that Trump knew how to turn such an odious appeal into both a performance and a spectacle — one that mimicked the darkest anti-democratic impulses.

The Struggle Continues

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]et’s hope the planet is around long enough to begin to rethink politics in light of this election of Donald Trump to the presidency, which ranks as one of the most sickening events in American political history. Democracy, however flawed, has now collapsed into Trump’s world, one led by a serial sexual groper, liar, nativist, racist and authoritarian. As my friend Bob Herbert mentioned to me recently, “Trump threatens everything we’re supposed to stand for. He’s the biggest crisis we’ve faced in this society in my lifetime. The Supreme Court is lost for decades to come. His insane tax cuts will only expand (and lock in) the extreme inequality we’re already facing. I don’t need to provide a laundry list for you. The irony of ironies, of course, is that the very idiots, racists, misogynists and outright fools who put him in the presidency will be among those hammered worst by his madness in office.”

The strategy of the left will be set back for years as a result of this election, given Trump’s propensity for vengeance, crushing dissent and sheer animosity toward anyone who disagrees with him. When he withdraws the US from the Paris Accords, goes after Black youth with his call for racial profiling, lowers taxes for the rich, deregulates business, sets back the Supreme Court for decades and expands the police state as he begins mass deportations, maybe we should rethink where the levers of power lie.

Amid this turmoil, we cannot let our anger simply become an expression of misdirected resentment. It is time to wake up and repudiate the notion that capitalism and democracy are the same thing. We must use our anger to fight collectively for a politics that refuses to forget the crimes of the past, so it can imagine a different future. Such a struggle is not an act of incivility, but a call to educated hope, civic courage and the need to start organizing.

![]()

Currently holds the Global TV Network Chair Professorship at McMaster University in the English and Cultural Studies Department and a Distinguished Visiting Professorship at Ryerson University. His books include: American at War with Itself, Zombie Politics and Culture in the Age of Casino Capitalism (Peter Land 2011), On Critical Pedagogy (Continuum, 2011), Twilight of the Social: Resurgent Publics in the Age of Disposability (Paradigm 2012), Disposable Youth: Racialized Memories and the Culture of Cruelty (Routledge 2012), Youth in Revolt: Reclaiming a Democratic Future (Paradigm 2013). Giroux’s most recent books are America’s Education Deficit and the War on Youth (Monthly Review Press, 2013), are Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education, America’s Disimagination Machine (City Lights) and Higher Education After Neoliberalism (Haymarket) will be published in 2014). He is also a Contributing Editor of Cyrano’s Journal Today / The Greanville Post, and member of Truthout’s Board of Directors and has his own page The Public Intellectual. His web site is www.henryagiroux.com.

Currently holds the Global TV Network Chair Professorship at McMaster University in the English and Cultural Studies Department and a Distinguished Visiting Professorship at Ryerson University. His books include: American at War with Itself, Zombie Politics and Culture in the Age of Casino Capitalism (Peter Land 2011), On Critical Pedagogy (Continuum, 2011), Twilight of the Social: Resurgent Publics in the Age of Disposability (Paradigm 2012), Disposable Youth: Racialized Memories and the Culture of Cruelty (Routledge 2012), Youth in Revolt: Reclaiming a Democratic Future (Paradigm 2013). Giroux’s most recent books are America’s Education Deficit and the War on Youth (Monthly Review Press, 2013), are Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education, America’s Disimagination Machine (City Lights) and Higher Education After Neoliberalism (Haymarket) will be published in 2014). He is also a Contributing Editor of Cyrano’s Journal Today / The Greanville Post, and member of Truthout’s Board of Directors and has his own page The Public Intellectual. His web site is www.henryagiroux.com.