By David Walsh

23 August 2017

Lewis increasingly fell out of favor with the public after the mid-1960s. He directed his last film, Cracking Up, in 1981-82. He continued to appear occasionally in films (and also television series) as an actor, including Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (1982) and Emir Kusturica’s Arizona Dream(1993).

The comedian was also renowned for his fundraising activities on behalf of the Muscular Dystrophy Association, hosting Labor Day telethons for more than four decades.

Lewis was born in Newark, New Jersey in March 1926 to Russian-Jewish parents. His father and mother were both performers, not terribly successful ones, in vaudeville and at Catskill Mountain resorts. Lewis was often left with his grandmother. He dropped out of Irvington High School at 15.

He teamed up with Martin when he was 19 and the singer was 27. Lewis recounts in a memoir how, without warning, he interrupted Martin’s performance one night, playing a rude waiter or busboy. He writes, “I have to admit, there was a heart-stopping moment when I wasn’t sure how he would react. … I figured him for a guy who didn’t take himself too seriously, who saw all of life as one big crazy joke.” Martin responded with amusement and the pair began regularly ad-libbing. Their nightclub act and radio program, including many appearances on early television, brought them national prominence.

In that same memoir, written with James Kaplan, Lewis asserts, “In the age of Truman, Eisenhower, and Joe McCarthy, we freed America. For ten years after World War II, Dean and I were not only the most successful show-business act in history—we were history. You have to remember: Postwar America was a very buttoned-up nation … We came straight out of the blue—nobody was expecting anything like Martin and Lewis. A sexy guy [Martin] and a monkey [Lewis] is how some people saw us, but what we really were, in an age of Freudian self-realization, was the explosion of the show-business id.”

Lewis and Kaplan note that while other comedy teams had worked with a script, “We exploded without one, the same way wiseguy kids do on a playground, or jazz musicians do when they’re let loose.”

Of course there’s an element of exaggeration and self-promotion here, but also a grain of truth. There was something spontaneous and also slightly threatening about the Martin-Lewis combination. Film critic Andrew Sarris commented a half-century ago, in his The American Cinema, “Martin and Lewis at their best—and that means not in any of their movies—had a marvelous tension between them. The great thing about them [as opposed to previous comedy teams] was their incomparable incompatibility, the persistent sexual hostility, the professional knowingness they shared about the cut-throat world they were in the process of conquering.”

Frank Tashlin directed probably the two best Martin-Lewis films, Artists and Models (1955), with Dorothy Malone and Shirley MacLaine, and Hollywood or Bust (1956), with Anita Ekberg. The latter film was released five months after Martin and Lewis split up as a comedy act.

In interviews, Lewis insisted that he had always been fascinated by every aspect of filming and made a regular habit of questioning crewmembers and technicians about their particular aspect of the filmmaking process. Tashlin, a former cartoonist, animator and gag writer, with his bold colors, fast pacing and numerous sight gags, had a strong impact on Lewis. Tashlin directed Lewis in six solo films, Rock-A-Bye Baby (1958), The Geisha Boy (1958), Cinderfella(1960), It’s Only Money (1962), Who’s Minding the Store? (1963) and The Disorderly Orderly (1964)

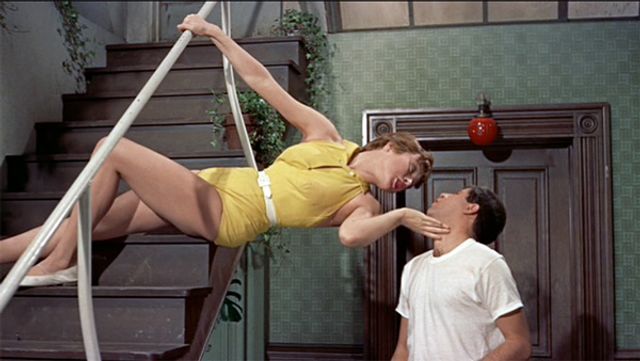

A sample of what Lewis could do, at his best (The Nutty Professor)

Lewis was a performer of extraordinary talent. At his improvisational and manic best, boasting a rapid-fire delivery, a variety of personas and all manner of physical contortions, he represented something anarchic and disruptive. He could be remarkably funny. Comics Robin Williams, Martin Short, Jim Carrey and many others were influenced by Lewis.

As noted above, his earliest films have a freshness and exuberance that makes them stand out. In The Bell Boy, a series of comic bits for the most part, Lewis is almost entirely silent. His earnest conducting of an imaginary orchestra (he began in comedy miming lyrics to songs on a phonograph) is especially memorable.

In the 1960s, Lewis became a favorite of a number of French film critics and commentators, including various figures at the Cahiers du cinéma and Positif magazines, along with postmodernist philosopher Gilles Deleuze. This subject matter has more to do with postwar French politics and philosophy than it does with the career of Lewis, who was something of a cat’s paw in many ways. For the most part, the adoption of (and even obsession with) Lewis was not a healthy development. A great deal of nonsense was written.

In some peculiar fashion, Lewis became one of the means by which various French critics justified their own social indifference or skepticism. In his often crude, self-referential, media-laden films, the commentators found something that appealed to them. It also confirmed their own dire opinions about America and American society.

Marcia Landy, professor of film studies at the University of Pittsburgh, observes, “What most endeared Lewis’s films to the Europeans from the 1950s to the present was their explicit illusionism, their anti-realistic realism, and their self-conscious and playful exploration of media. Lewis’s fantasies, his use of slapstick and gags, are interpreted as a critique of realism and therefore as a critique of a naive belief in the world as seen.

“These European critics regard Lewis’s films as an assault on American culture and politics, exposing a banality that masks more aggressive designs. In particular, in the childlike character that so many of his critics have commented upon, his persona raises the juvenilization of American culture to the point of absurdity.”

None of this was Lewis’s fault, but he undoubtedly allowed the misguided French commentaries to go to his head. His films became increasingly pretentious and self-conscious in the 1960s.

Sarris had the best things to say about Lewis at the time, and it seems worthwhile citing him at length. He noted that “the Pirandellian ending of The Patsy is proof enough of [Lewis’s] expanding ambitiousness. That the ending doesn’t come off indicates that Lewis’s aspiration now exceeds his ability.” Sarris also noted the “chasm” between “Lewis’s verbal sophistication in nightclubs and sometimes on television and his simpering simplemindedness on the screen.”

The critic went on: “When Lewis decides he has something to say, it comes out conformist, sentimental and banal. He was quite funny laughing at Hedda Hopper’s hat in The Patsy, but then he has to go spoil it all by letting dear Hedda make a speech about the importance of being sincere in Hollywood. The clown’s speech in The Family Jewels might have been conceived in the mind of any smug superpatriot as a sermon on what showbiz folk owe dear old Uncle Sam. The point here is not Lewis’s politics, but his sanctimoniousness.”

Finally, “The trouble is that he [Lewis] has never put one brilliant comedy together from fade-in to fade-out. We can only wait and hope, but the suspicion remains that the French are confusing talent with genius.” He never did make such a work.

For all his comic vigor and youthful rebelliousness, Lewis was still a product of the anticommunist Cold War years, “the age of Truman, Eisenhower, and Joe McCarthy.”

“Freeing” America, it hardly seems necessary to point out, would have taken more than an innovative, volatile nightclub act.

A popular and commercial success at a young age, Lewis never seriously troubled himself with critical thoughts about American society and its assumptions. He remained largely on the surface, although at times it was a fascinating, pleasurable surface. When the initial burst of energy, anger and enthusiasm dissipated, as it must for every performer sooner or later, there was not something substantial to sustain Lewis. The last half of his life was characterized by severe decline.

BONUS FEATURE

Gene Siskel commentary on The King of Comedy, one of the great films in which Jerry Lewis appears but not playing his comedic persona.

When Lewis decides he has something to say, it comes out conformist, sentimental and banal. He was quite funny laughing at Hedda Hopper’s hat in The Patsy, but then he has to go spoil it all by letting dear Hedda make a speech about the importance of being sincere in Hollywood. The clown’s speech in The Family Jewels might have been conceived in the mind of any smug superpatriot as a sermon on what showbiz folk owe dear old Uncle Sam.

When Lewis decides he has something to say, it comes out conformist, sentimental and banal. He was quite funny laughing at Hedda Hopper’s hat in The Patsy, but then he has to go spoil it all by letting dear Hedda make a speech about the importance of being sincere in Hollywood. The clown’s speech in The Family Jewels might have been conceived in the mind of any smug superpatriot as a sermon on what showbiz folk owe dear old Uncle Sam.

![]()

[premium_newsticker id=”154171″]