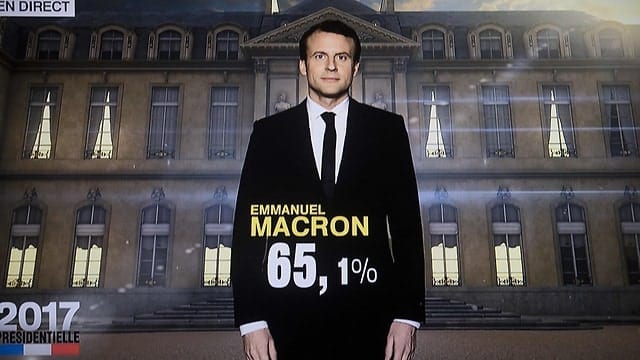

French legislative elections follow hard on the heels of the Presidential election. The momentum virtually ensures a presidential majority. So it was taken for granted that voters would give President Emmanuel Macron a docile parliament for his five-year mandate.

But these elections were exceptional. The victory of Macron’s personal party, la République En Marche (REM), is novel in several ways. Not only has REM won an absolute majority of 350 out of 577 seats in the National Assembly. REM’s victory has also bled the two traditional governing parties, the Republicans and the Socialists, perhaps fatally.

With over 130 seats, the Republican Party of former President Nicolas Sarkozy and its allies came in second, and thus ranks as leading opposition party. But since Macron successfully lured two Republican politicians into prominent positions in his government – Edouard Philippe as Prime Minister and Bruno LeMaire as Economics Minister – it is hard even for the Republicans’ current leader, François Baroin, to explain just what they will oppose. How can they be a “right-wing opposition” to a government that intends to tear down the Labor Code, leaving workers at the mercy of employers, to deregulate the economy, to privatize, and to promote European militarization?

The plight of the Socialists is even more dire. Despite their strong historic implantation throughout the country, they won only 29 seats (which with small party allies gives them a group of 45 deputies). Most of the prominent members of Hollande’s government who dared to run were defeated. Former Prime Minister Manuel Valls’ close victory in the town where he used to be mayor is being vehemently contested, by angry crowds, with accusations of cheating.

As an opposition party, the Socialists’ predicament is even worse than that of the Republicans. Macron was a pet advisor to Socialist President François Hollande, a minister of economics in his government, and was sponsored by leading Socialists as a way to perpetuate their own surrender to high finance. Since many of leading Socialist Party personalities have joined or endorsed Macron, the survivors are not sure whether to support him – or how not to. The confusion is total.

The result is that by cannibalizing the two discredited government parties, and adding a large contingent of political amateurs (described as representatives of “civil society”), Macron and his  team have succeeded in creating a new form of single party state. The new majority of deputies in the National Assembly are not there to represent ideas, or a program, or local constituencies, but simply to represent… Emmanuel Macron. From the looks of it, he can do whatever he wants, and the parliament will approve.

team have succeeded in creating a new form of single party state. The new majority of deputies in the National Assembly are not there to represent ideas, or a program, or local constituencies, but simply to represent… Emmanuel Macron. From the looks of it, he can do whatever he wants, and the parliament will approve.

Macron’s victory was both overwhelming and underwhelming. All records of abstention were broken; for the first time in over a century, a majority of eligible voters stayed away from the polls in the first round of the parliamentary elections, and abstention rose to 57% in the second round. He owes his landslide to less than 20% of registered voters.

There is no doubt that the election results reveal a rejection of traditional parties, of politicians, and to some extent even a rejection of electoral politics. This is a foreseeable result of the so-called “power of the markets” – which disempower the voters. Political elites have surrendered to the dictates of financial capital, primarily through the intermediary of the European Union, where economic policy is designed and imposed on Member States. Presented as “new”, Macron is simply more intent than his predecessors on pushing through EU economic policies, on behalf of the big banks and at the expense of everyone else. But many of those who voted for him did so fatalistically: “let’s give him a chance”, like playing the lottery.

Indeed, Macron ran as himself, “young, vigorous, optimistic” in a time of pessimism, and not as a program. And the election season showed that personalities counted more than parties or programs. The two most charismatic personalities in French politics, Marine Le Pen and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, after their strong scores in the presidential elections, were both comfortably elected to the National Assembly from friendly districts (he in Marseilles and she in the depressed industrial north), but their followers did not rush to the polls to support their respective parties. Mélenchon’s party, La France Insoumise, won only 17 seats, which together with ten communists could make a group of 27 deputies.

As for Marine Le Pen, her National Front won only eight seats, four from the traditionally socialist north (including Marine), and four from the right-leaning south (including Marine’s life partner, Louis Aliot). That reflects the ideological division in the party. In the Calais region, the winning National Front leader was a former regional Communist Party leader, José Evrard, who comes from a family of coal miners and anti-Nazi resistants. The intellectual leader of the left tendency, Florian Philippot, was not elected, but plans to work to create a broader “sovereignist” movement opposing Macron’s drive to integrate France irreparably into Western globalizing economic and military structures.

In short, President Emmanuel Macron is intent on using his unprecedented single party powers to reduce the power of France by intensifying its commitment to globalization. But how much power does he really have, or is he an instrument of other powers?

Chief power guru, Jacques Attali, tends to glorify himself shamelessly, but when he says that he is “very proud” of having launched Macron’s brilliant career, he is telling the unchallenged truth. As for the next President after Macron, Attali claims to know “who she is”, as well.

But whoever he or she may be, Attali’s point is that genuine power is not exercised by politicians any more, but by financial institutions. The President of the Republic has much less

power than people think, he told a recent television panel. One reason is the euro, he said, which “means that a large part of economic policy has fortunately become European.

Decentralization, major investments and major infrastructures are no longer up to the State. Globalization and the market have won hands down. There are a large number of things that were thought to be up to the government and no longer are.”

Presidents “no longer have real power over society.”

As for getting out of the clutches of European dictates, Attali boasts that those who, like himself, took part in writing the first versions of the EU treaties “made sure that getting out is no longer possible.”

“The market is going to spread to sectors to which it hasn’t had access until now such as health, education, the courts, the police, foreign affairs…” The outcome will be a dominant market which causes more and more concentration of wealth, growing inequality, absolute priority to the short term and to the tyranny of the present instant and of money, Attali concedes cynically.

A fairly realistic sense of powerlessness underlies the high abstention rate and the search for a providential leader. Since the Socialists and the Republicans have been contaminated with Macronism, the serious parliamentary opposition is reduced to the small party of Mélenchon and the still smaller party of Marine Le Pen. Mélenchon has the oratorical skill to be the leading opposition voice within and even outside the new Parliament. Marine still commands strong personal loyalty. But as long as they fail to find common ground, the Macron machine will play on their differences to marginalize them as the “extreme right” and the “extreme left”. And French democracy will continue to be disempowered by global governance. The single party state is at least an accurate expression of that reality.

Diana Johnstone is the author of Fools’ Crusade: Yugoslavia, NATO, and Western Delusions. Her new book is Queen of Chaos: the Misadventures of Hillary Clinton. She can be reached at diana.johnstone@wanadoo.fr

Diana Johnstone is the author of Fools’ Crusade: Yugoslavia, NATO, and Western Delusions. Her new book is Queen of Chaos: the Misadventures of Hillary Clinton. She can be reached at diana.johnstone@wanadoo.fr

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” — acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump — a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” — acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump — a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report