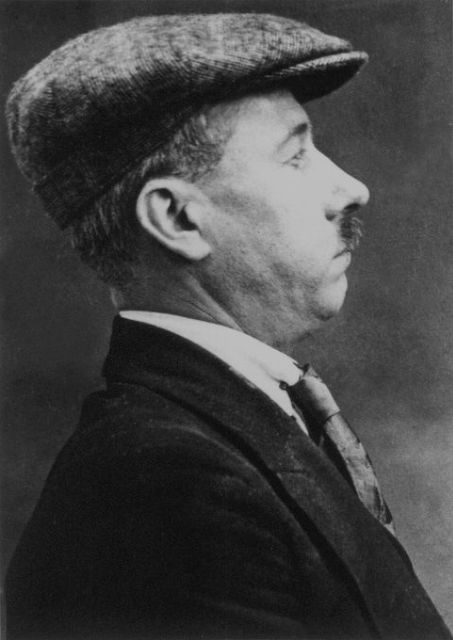

B. Traven, the author of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

By David Walsh, wsws.org

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, the novel on which John Huston based his 1948 film, was published in German in 1927 and in English in 1935. It concerns three Americans and their back-breaking efforts to find gold in the desolate Mexican countryside. Their success leads ultimately to tragedy.

The novel’s author was the left-wing writer known as B. Traven. Considerable mystery surrounds Traven, some of it sustained by the writer himself during his lifetime. It is not the purpose of this brief article to add anything to the speculation about his life and career, but rather to recommend his works to readers who may not be aware of them.

The general consensus these days seems to be that Traven was the name adopted by the German actor, journalist and anarchist, Ret Marut. Marut was itself a pseudonym, perhaps for one Otto Feige, born in 1882 in Schwiebus in Brandenburg, modern-day Poland. Marut appeared on the stage before World War I, by which time he had become radicalized.

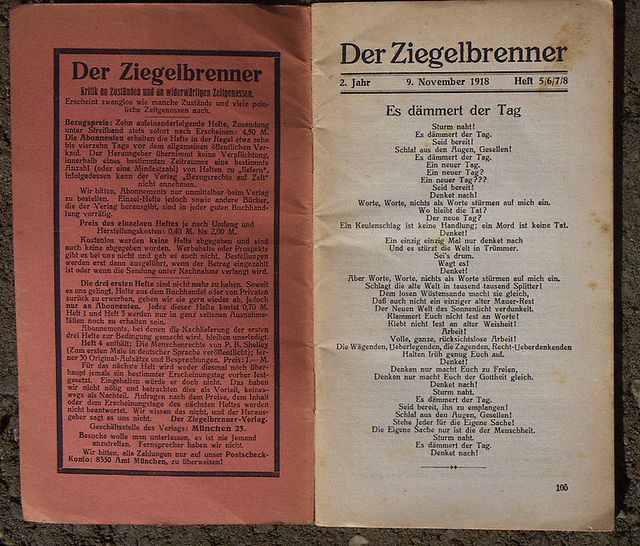

According to James Goldwasser, “In September 1917, Marut launched Der Ziegelbrenner [“Brickburner” or “Brickmaker”], a radical, anti-war, individual-anarchist magazine, most of which he wrote himself. Thirteen issues of Der Ziegelbrennerappeared during the following five years.” In other words, Marut continued publishing his journal after the collapse of the German Empire and the regime of Wilhelm II in November 1918, followed by the failed German revolution of 1918-19.

Goldwasser further explains, “Having 6,000 copies of one number in print was surely the high point of Ziegelbrenner business. It must have declined somewhat in the post-war climate, in spite of the easing of paper restrictions. In peacetime, Marut would have lost a number of subscribers who had been attracted to his anti-war posture but did not necessarily sympathize with the [German] revolution that followed and which was trumpeted by Marut with the same headline used by Lenin’s Pravda in Russia: ‘The World Revolution Has Begun!’”

In April 1919 Marut played a role in the establishment of the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic, and, in fact, was an official in the revolutionary government. After the Soviet Republic’s brutal suppression by White troops, “Marut, by his own account in Der Ziegelbrenner, narrowly escaped summary execution. He spent the next three years underground, attempting to keep his magazine in circulation, and eventually fled the continent sometime in 1923.”

By one means or another, the future novelist arrived in North America and, eventually, Mexico. His first novel, The Cotton Pickers, explains one commentator, “dealt with the Mexican adventures of an American ‘Wobbly’ or member of the Industrial Workers of the World. … This was based on Traven’s working experiences when he first arrived in Mexico, in a variety of manual jobs.” The novel was first published in a Social Democratic Party daily paper in Berlin in 1925.

By one means or another, the future novelist arrived in North America and, eventually, Mexico. His first novel, The Cotton Pickers, explains one commentator, “dealt with the Mexican adventures of an American ‘Wobbly’ or member of the Industrial Workers of the World. … This was based on Traven’s working experiences when he first arrived in Mexico, in a variety of manual jobs.” The novel was first published in a Social Democratic Party daily paper in Berlin in 1925.

In 1926, The Death Ship appeared, which apparently included autobiographical details of his harrowing sea journey to the New World. By this time, Traven’s style had emerged, a combination of strong opposition to authority, ironic banter, and down-to-earth, authentic dialogue and action.

The hero of the novel. Gerard Gales, manages to miss his ship in Antwerp, which leaves him without money or papers of any kind. This is how he describes his reaction to that sad turn of events:

“I have seen children who, at a fair or in a crowd, had lost their mothers. I have seen people whose homes had burned down, others whose whole property had been carried away by floods. I have seen deer whose companions had been shot or captured. All this is so painful to see and so very sorrowful to think of. Yet of all the woeful things there is nothing so sad as a sailor in a foreign land whose ship has just sailed off leaving him behind.

“It is not the foreign country that makes him so sick at heart, that makes him feel inside like a child crying for its mother. He is used to foreign countries. Often he has stayed behind of his own free will, looking for adventure, or for something better to turn up, or out of dislike for the skipper or the mates or some fellow-sailors. In all such cases he does not feel depressed at all. He knows what he is doing and why he did it, even when it turns out different from what he expected.

“But when the ship of which he considers himself still a useful part sails off without taking him with her, without waiting for him, then he feels as though he had been torn asunder. He feels like a little bird may feel when it has fallen out of its nest. He is homeless. He has lost all connection with the rest of the world, he thinks; he has lost his right to be of any use to mankind. His ship did not bother to wait for him. The ship could afford to sail without him and still be a good and seaworthy ship. A copper nail that gets loose, or a rivet that breaks off, might cause the ship to sink and never reach home again. The sailor left behind, forgotten by his ship, is of less importance to the life and the safety of the ship than a rusty nail or a steam-pipe with a weak spot. The ship gets along well without him. He might as well jump right from the pier into the water. It wouldn’t do any harm to the ship that was his home, his very existence, his evidence that he had a place in this world to fill. If he should now jump into the sea and be found, nobody would care. All that would be said would be: ‘A stranger, by appearance a sailor.’ Worth less to a ship than a nail.”

Gales eventually ships out on the Yorikke, a ship so rotten and decrepit that it is worth more to its owners overinsured and sunk than it is afloat. Hence, the “death ship.” The material is often grim and harsh, but the tone is confident and even jaunty, blackly comic. The working class and the oppressed at this time drew immense strength from the revolutionary wave of the postwar period, especially of course the October Revolution in 1917. The power of the working class also influenced and guided the most conscious artists of the day.

Gales eventually ships out on the Yorikke, a ship so rotten and decrepit that it is worth more to its owners overinsured and sunk than it is afloat. Hence, the “death ship.” The material is often grim and harsh, but the tone is confident and even jaunty, blackly comic. The working class and the oppressed at this time drew immense strength from the revolutionary wave of the postwar period, especially of course the October Revolution in 1917. The power of the working class also influenced and guided the most conscious artists of the day.

Whatever Traven’s conceptions may have been, Bolshevism, as an example, as a threat, hangs over the crew and the events in The Death Ship. Taken in by the cops, for example, Gales reports, “Upon coming to the police-station I was searched. This was done with all the cunning they had. Tearing open even seams. Still thinking of spies, I thought. But later it dawned upon me that they were looking, whenever they caught a sailor, for Bolshevik ideas rather than for photographs of fortresses or warships.” When Gales is thinking up a plan by which he can get himself fired, he mused, “Or I might go to the old man directly and tell him I am a Bolshevist, and I have got it in mind to get up the whole crew, and we would take over the ship and run her for our own benefit or sell her to Russia.”

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was published in German in 1927, in English in 1935. It was a commercial success for Knopf, and Warner Bros. studio bought the rights to the film in 1941.

In the 1930s, Traven wrote the extraordinary series of six novels known as the Jungle Novels. A commentator observes, “The six novels known as the Jungle, or the Mahogany Series, comprise a large and comprehensive history of the peons, carters, loggers and forced laborers of southeast Mexico in the early days of the last century. Though the novels are whole, giving due attention to the white oppressors, the emphasis is on the lowly Indians in their normal life, in their submission to oppression, and in their successful revolt against white owners.”

The fifth novel in the series is The Rebellion of the Hanged. The story is as dramatic as its title. No one who reads the book is likely to forget it. The same commentator writes, “In the monterías [the mahogany labor camps] , the peons were hung alive by their four members (and sometimes five) in the trees as punishment for failing to fell and trim four tons of mahogany logs each day. Under such treatment, and in face of the eighty-per-cent death rate in the camps, the peons rebelled, overcame their masters, burnt the camps, and began to march out of the jungle towards the capitals. Though they heard only rumors from the north, the Revolution was already breaking out in scattered points and would soon result in the overthrow of dictator [Porfirio] Díaz.”

The final book, first published in 1939, The General from the Jungle, centers on “a youthful Chamula Indian [the “general” of the title] who outwits the educated and well-trained generals of Porfirio Díaz. Liberating persecuted, enslaved Indians and leading a ‘mob’ of men, women and children, the rebels move out of the jungle towards the towns. There is a succession of battles, both in the fields and around the walls of fortified haciendas…More than being another fine novel of rebellion and guerrilla warfare, it is a satire on national armies, as well as a rebuke to warfare, no matter how just the cause.”

If the Marut thesis is correct, the writer Traven had good reason to keep his identity a secret in the years following the failed 1919 revolution in Germany. Fellow leading members of the Soviet Republic and many workers and left-wingers had been executed or simply murdered in the streets. Marut was wanted in Germany for treason.

At the time of the preparation for the filming of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Traven communicated with director John Huston. In September 1946, for example, he wrote Huston a letter in which he acknowledged he was “delighted over your script. It goes as close alongside the book as a picture ever will allow.” One of the aspects Traven admired about the script was that “you didn’t sugar-coat” the novel “and that you saw no reason doing so.” Traven did suggest a few changes, some of which Huston accepted.

At the time of the preparation for the filming of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Traven communicated with director John Huston. In September 1946, for example, he wrote Huston a letter in which he acknowledged he was “delighted over your script. It goes as close alongside the book as a picture ever will allow.” One of the aspects Traven admired about the script was that “you didn’t sugar-coat” the novel “and that you saw no reason doing so.” Traven did suggest a few changes, some of which Huston accepted.

In 1946, Huston arranged to meet Traven at a hotel in Mexico City. An individual identifying himself as Hal Croves, a translator armed with an alleged power of attorney from Traven, showed up instead. “Croves” was present as a technical advisor during the Mexican portion of the shooting of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre in 1947. It is now generally believed that Croves was Traven himself. The writer died in Mexico City in 1969.

His writing belongs to that very general category of left-wing fiction and drama that flourished for a brief time in the 1920s and 1930s in Europe. Works as disparate as Jaroslav Hašek’s The Good Soldier Švejk and Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz come to mind.

Writing about Jean Malaquais’ Les Javanais (1939, translated into English as Men From Nowhere ), Leon Trotsky took note of certain qualities: “Although social in its implications, this novel is in no way tendentious in character. He does not try to prove anything, he does not propagandize, as do many productions of our time, when far too many submit to orders even in the sphere of art. … At the same time we sense at every step the convulsions of our epoch, the most grandiose and the most monstrous, the most significant and the most despotic ever known to human history. The combination of the rebellious lyricism of the personality with the ferocious epic of the era creates, perhaps, the chief fascination of this work.”

Traven’s work might be described in somewhat similar terms. It deserves modern readers.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License