Revisiting history: Kautsky on Christianity

Editor's Note: As one of the earliest social democrats to abandon and later denounce the Leninist approach to revolution (making the idea of "evolutionary socialism" respectable among some anticapitalist circles), and thereby slowing down and splitting the movement, Karl Kautsky, the onetime close friend and secretary to Friedrich Engels, and founder in 1883 of the monthly Die Neue Zeit ("The New Times") in Stuttgart, played an objectively disgraceful role in humanity's struggle against capitalism. There is little doubt that viewed in that manner (Vladimir Lenin himself described Kautsky as a "renegade" in his classic pamphlet "The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky"), Kautsky should be seen as a notorious apostate, an "anticommunist leftist" like many other notorious turncoats throughout much of the 20th century, a corrosive strain that continues unabated to this day. But Kautsky's treacherous collaboration with chauvinist capitalist forces should not obscure his claim to scholarship and expertise in certain subjects, such as the rise and entrenchment of Christianity—a variant of Judaism— in Western culture, and the history of Jews themselves, a field of study in which he eventually produced his seminal tome Foundations of Christianity: A Study of Christian Origins (First published in 1908, revised in 1925 edition). Materials of this sort are essential to acquire a modicum of political literacy. One need not agree with nor accept everything that Kautsky says to value his research, some of it inevitably rendered obsolete or contradicted by more recent findings. Our appendix carries two sample sections of this thought-provoking book. Be sure to examine them.—PG

By Shelley Ettinger, workers' world

The German Marxist Karl Kautsky, in his 1908 book "Foundations of Christianity," made a scholarly examination of the class relations and material conditions of life in the time and place in which Jesus was supposed to have lived.

The vast majority of Jews were desperately poor. The Roman military occupiers ruthlessly exploited and suppressed them. Because of all this, it was a period of great social turmoil. Movements arose to organize rebellion.

Rome, with its vast military might, struck back. Each attempt at insurrection was met by horrific violence.

According to Kautsky, a shepherd named Athronges led a mass uprising just before Jesus was born. Roman legions, with great difficulty, crushed the insurrection. "There began an unspeakable slaughtering and plundering; 2,000 of those captured were crucified, many others sold into slavery."

Of Jesus of Nazareth, Kautsky wrote: "Tradition declared that the Romans had crucified Jesus as a Jewish Messiah, a king of the Jews, in other words, a champion of Jewish independence, a traitor to Roman rule."

Kautsky emphasized that the Jewish masses had just welcomed Jesus into Jerusalem. "It therefore follows ... that the Jews sympathized with Jesus" and would have had no reason to call for his death.

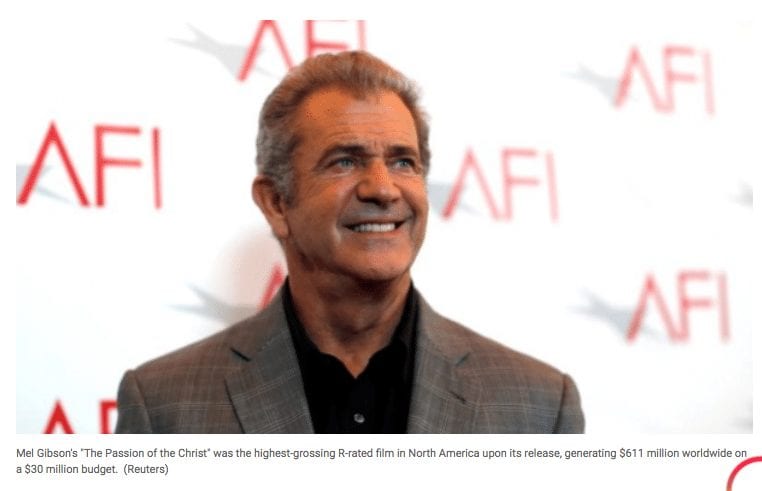

In light of Mel Gibson's claim that he "stuck to the Gospels" in his cinematic version that blames Jewish people for Jesus's execution, Kautsky's observations are pertinent. He pointed out, as have many scholars since, that the four Gospels were written long after everyone who might have been present at Jesus's execution had died.

Mel Gibson's rancid Christian fundamentalist beliefs—a form of deeply embedded and pernicious cultural ignorance preponderant in the United States—fused to colossal and crass commercialism, his Hollywood DNA, have further polluted the historiography surrounding Christ and the role of the Jews in his execution. In fact, the very personhood of Christ remains a matter of contention for serious scholars, including his race, usually (and ludicrously) depicted in the West as a man of nordic Caucasian ethnicity.

By this time, "Christianity was now in open opposition to the Jews, and wished to be on good terms with the Roman authorities. It was now important to distort the tradition in such a manner as to shift the blame for the crucifixion of Christ from the shoulders of the Romans to those of the Jews, and to cleanse Christ not only from every appearance of the use of force, but also from every expression of pro-Jewish, anti-Roman ideas."

Many commentators have taken Mel Gibson to task for exonerating the Roman oppressors and blaming the Jewish oppressed for the suffering and death of Jesus, which, Kautsky said, "was for many centuries one of the best means of arousing hatred and contempt for the Jews."

Kautsky classified the crucifixion as "an incident in the history of the sufferings of the Jewish people."

Reprinted from the March 18, 2004, issue of Workers World newspaper

MIA > Archive > Kautsky > Christianity

Karl Kautsky: Foundations of Christianity

Book Three: The Jews

Karl Kautsky

Foundations of Christianity

Book Three: The Jews

I. Israel

Migrations of the Semitic Peoples

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]HE BEGINNINGS Of the Jewish history are as obscure as those of Greek or Roman history, or even more so. For many centuries these beginnings were preserved only orally and when the old legends were finally collected and written down, they were distorted in the most one-sided and partisan manner. Nothing could be more mistaken than to take the Bible story as an actual historical account. The stories have a historical core, but it is extremely difficult to get at.

Charlton Heston as Moses in Cecil B. DeMille's biblical extravaganza The Ten Commandments (1956). In his sloppy and cartoonish use of history DeMille was no less a master of chicanery than Gibson.

It was only long after the return from Babylonian exile, in the fifth century, that the “holy” scriptures of the Jews were given the form in which we know them today. All the old traditions were ceremoniously refurbished and added to, in order to help the pretensions of the rising theocracy. In the process all of early Jewish history was turned topsy-turvy. This is especially true of everything that is related of the religion of Israel before the Exile.

When, after the Exile, Judaism founded a community of its own in Jerusalem and the surrounding territory, the other nations were struck by its singularity, as we learn from many sources. On the other hand, no such testimony has come down to us with respect to pre-Exile times. Down to the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians the Jews were regarded by the other nations as a people like any other, with no special characteristics. And we have every reason to assume that up to that time the Jews actually were not odd or unusual in any way.

It is impossible to outline a picture of ancient Israel with any certainty, given the scarcity and the unreliability of the sources that have come down to us. Bible criticism by Protestant theologians has already shown that a great deal of it is spurious and fictitious, but tends far too much to take as gospel truth everything not yet proved to be obviously counterfeit.

Basically we are reduced to hypotheses when we try to form an idea of the course of the development of Israelite society. We can make good use of the stories of the Old Testament to the extent that it is possible for us to compare them with descriptions of peoples in similar situations.

The first authentic appearance of the Israelites on the stage of history is their invasion of the land of the Canaanites. All the stories of their nomadic era are either old tribal legends and tales reworked for propaganda purposes, or later fabrications. They come into history as participants in a great Semitic migration.

The migrations played a role in the ancient world comparable to today’s revolutions. In the last book we became acquainted with the decline of the Roman Empire, and saw the way in which its inundation by the Germanic barbarians, an event called a migration, was built up and prepared. It was not an unprecedented event. It had repeatedly occurred in the old Orient on a smaller scale, but from similar causes.

In the fertile basins of many of the great rivers of the Orient there early arose an agriculture that produced considerable surpluses of foodstuffs which not only supported the peasants but enabled a numerous supplementary population to live and work. Crafts, arts and sciences flourished there; but an aristocracy too was formed, which could devote itself exclusively to the trade of arms and was all the more needed because the wealth of the river-basin tempted warlike nomadic neighbors to robber raids. If the farmer wanted to cultivate his field in peace, he needed the protection of such aristocrats and had to buy it. As the aristocracy became stronger, it was natural for it to attempt to use its military power to increase its revenues, particularly since the flourishing of the arts and crafts gave rise to all sorts of luxury, which required great wealth.

The oppression of the peasants begins at this point, together with slave-hunting campaigns by the better-armed aristocrats and their vassals against the neighboring peoples. Forced labor begins and drives society into the same blind alley in which the society of the Roman Empire was later to end up. The free farmer is ruined and replaced by forced laborers. But that means that the basis of the empire’s military power disappears; the aristocracy, despite its highly-developed military technique, loses its military superiority, unmanned by growing luxury.

They lose the qualities they need to perform the function on which their social status was based: that of defending the community against the inroads of plundering neighbors. These neighbors see the growing weakness of the rich and tempting prey; they press harder and harder on its borders and finally overflow it, unchaining a movement that extends to more and more nations pressing onward and continues for a long period. A part of the invaders takes possession of the land and creates a new free peasant class. Others who are stronger form a new military aristocracy. At the same time the old aristocracy can still maintain a superior status as guardian of the arts and sciences of the old civilization, no longer as a caste of warriors, but only as a caste of priests.

Once the migration has come to rest, the development of the cycle begins all over again, more or less comparable to the cycle of prosperity and crisis in capitalist society – although not a ten-year cycle, but one that takes many centuries, a cycle that was first eliminated by the capitalist mode of production.

This course of events went on for thousands of years in the most diverse regions of Asia and North Africa, most strikingly in regions where broad fertile river valleys are next to steppes or deserts. The valleys produce mighty riches, but in the end they produce deep-reaching corruption and effeminacy as well. This makes it possible for poor but warlike nomad nations to develop who are always ready to change their location when there is a chance of booty, and can come together quickly in countless hordes from distant regions to make a devastating assault on a single district.

Such river valleys were those of the Yellow River and Yangtze-kiang, in which the Chinese community took form; of the Ganges, in which India’s wealth was concentrated; of the Euphrates and Tigris, where the mighty empires of Babylonia and Assyria arose; and finally of the Nile, in Egypt.

In contrast Central Asia on the one hand and Arabia on the other constituted inexhaustible reservoirs of warlike nomads who made life miserable for their neighbors and from time to time took advantage of their neighbors’ weakness to make mass invasions.

Out of Central Asia from time to time, in such periods of weakness, floods of Mongols and occasionally of so-called Indo-Germans overflowed the banks of civilization. Out of Arabia there came those peoples to whom we give the common name of Semites. Babylonia, Assyria, Egypt and the Mediterranean coast in between were the goals of the Semitic invaders.

Toward the end of the second millennium before Christ another great Semitic migration sets in, driving toward Mesopotamia, Syria and Egypt, and coming to an end roughly in the eleventh century B.C. Among the Semitic stocks that conquered neighboring civilized countries at that time were the Hebrews. In their Bedouin-like wanderings they may previously have been at the Egyptian border and on Sinai, but it was only after they had succeeded in establishing themselves in Palestine that they take on a fixed character and emerge from the stage of nomadic instability, in which no durable national unities are formed.

Palestine

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]rom now on the history and character of the Israelites was determined not only by the qualities they had acquired on the Bedouin stage and retained for some time thereafter, but also by the nature and situation of Palestine.

The influence of the geographical factor in history should not of course be exaggerated. The geographical factor – position, contour, climate – remains more or less the same in most countries over the course of history; it is there before history and certainly has a tremendous effect on that history. But the way in which that effect is produced depends in turn on the level to which technology and social relations have developed in the country in question.

Thus the English would certainly never have reached their position of world dominance during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries without the special nature of their country, without its wealth in coal and iron and its insular position. But so long as coal and iron did not have that dominant role in technology that they acquired in the era of steam, these natural riches of the soil had only slight significance. And until America and the sea route to India had been discovered, the techniques of sailing highly developed, and Spain, France and Germany highly cultivated; so long as these countries were inhabited by mere barbarians, England’s insular position was a factor shutting it off from the civilization of Europe and keeping it weak and barbarous.

Under different social conditions the unchanging nature of the land can have a quite different significance; even where the nature of the country is not altered by the change in the modes of production, its effect does not necessarily remain the same. Here too we always come up against the totality of economic relationships as the decisive factor.

It was not therefore the absolute nature and position of Palestine, but that nature and position under determinate social relationships, that determined the history of Israel.

The peculiarity of Palestine was that it was a border region, where hostile elements collided and fought. It lay in a place where on one side the Arabian desert came to an end and the Syrian civilized country began, and on the other the spheres of influence of the two great empires clashed: the Egyptian empire in the valley of the Nile, and the Mesopotamian on the rivers Euphrates and Tigris, with its capital now at Babylon and now at Nineveh.

Finally, Palestine was crossed by very important trade routes. It controlled traffic between Egypt on the one side and Syria and Mesopotamia on the other, together with commerce between Phoenicia and Arabia.

Let us consider the effects of the first factor. Palestine was a fertile land; its fertility was nothing out of the ordinary, but it seemed sumptuous compared with the deserts of sand and stone nearby. For the inhabitants of those wastelands it seemed a land flowing with milk and honey.

The Hebraic clans came as nomadic herdsmen; their settling down took place in constant battle with the native inhabitants of Palestine, the Canaanites, from whom they took one city after another, forcing them into submission. But what they had won in constant war they had to keep by constant warfare, for other nomads came after them who were just as eager as they were to own the fruitful land, Edomites, Moabites, Ammonites and others.

Even after conquering the land the Hebrews remained herdsmen for a long time, although they were now sedentary. However they gradually took over from the original inhabitants their mode of agriculture, the growing of grain and wine, the culture of olive and fig trees, etc., and intermixed with them. But they kept for a long time the character traits of the nomadic Bedouin tribes from which they came. Nomadic cattle-raising in the desert seems to be particularly unfavorable to technological progress and social development. The way of life of the Bedouins of Arabia today still reminds us strongly of that described in the old legends of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Out of the centuries there came down from generation to generation eternal repetition of the same activities and sufferings, the same needs and views, ending in a bitter conservatism, which is even stronger in the nomad herdsman than in the peasant, and favors the preservation of old customs and institutions even in the presence of great changes.

As an example of this tendency, the hearth had no fixed position in the house of the Israelitish peasant, and no religious significance. “In this point the Israelites come close to the Arabs and differ from the Greeks, to whom they are much closer in the other aspects of daily life,” says Wellhausen, adding: “Hebrew hardly has a word for the hearth; the name ‘aschphot’ has significantly taken on the meaning of ‘rubbish heap’. That shows the difference from the Indo-European hearth, the house altar; instead of the hearth fire that never goes out, the Hebrews had the eternal lamp.” [1]

Among the qualities that the Israelites carried over from their Bedouin period should be included the inclination for trading. Above, in studying Roman society, we pointed out how early trade among peoples developed. Its first agents must have been nomadic herdsmen of the desert. Their way of earning a living compelled them to wander ceaselessly from one pasture to another. The meager nature of their land must very early have aroused in them the need for products of other richer countries bordering on their own. They traded, perhaps, their surplus cattle for grain, oil, dates, or tools of wood, stone, bronze and iron. Their mobility enabled them however not merely to get products for themselves from distant parts, but also to barter desirable and easily transportable products for other people; that is, not for the purpose of keeping them and consuming or enjoying them for themselves, but for the purpose of surrendering them against compensation. They were thus the first merchants. So long as there were no roads and sea travel was poorly developed, this form of commerce must have predominated, and could lead to great riches for those who carried it on. Later, as sea travel increased and safe and practicable roads were built, this sort of trade through nomads must have decreased, and the nomads, reduced to the products of their deserts, must have grown poor. That must be at least in part the reason why the old civilization of Central Asia has declined so since the discovery of the sea route to the East Indies. Earlier, Arabia became poor for the same reason; at the time the Phoenician cities flourished the Arabian nomads carried on a very profitable trade with them. They delivered the valued wool of their sheep to the city looms working for export to the West; they also brought the products of the rich and fertile Arabia Felix to the south, frankincense, spices, gold and precious stones. In addition, they brought from Ethiopia, which is separated from Arabia Felix only by a narrow body of water, precious goods like ivory and ebony. The trade with India too passed chiefly through Arabia; to its coasts on the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean goods came by ship from Malabar and Ceylon and then were taken across the desert to Palestine and Phoenicia.

This trade brought considerable wealth to all the tribes through whose hands it passed, partly through the merchant’s profit, partly through the duties imposed on the wares as they passed through.

“It is common to find very rich tribes among these peoples,” says Heeren. “Among the Arabian nomads none seem to have carried on caravan trade with more profit than the Midianites, who used to rove near the northern border of this land, near Phoenicia. It was a caravan of Midianite merchants loaded with ‘spicery and balm and myrrh’, going from Arabia to Egypt, to whom Joseph was sold (Genesis 37, verse 28). The Israelites got so much booty in gold from this people when Gideon drove back an invasion of the Midianites into Gilead that it caused amazement; the metal was so common among them that it was used not only for personal adornment but even for the camels’ collars.”

The eighth chapter of Judges tells us:

“And Gideon arose, and slew Zebah and Zalmunna, and took away the ornaments (or, ornaments like the moon) that were on their camels’ necks ... And Gideon said unto them (the men of Israel), I would desire a request of you, that ye would give me every man the earrings of his prey. (For they had golden earrings, because they were Ishmaelites.) ... And the weight of the golden earrings that he requested was a thousand and seven hundred shekels [2] of gold, beside ornaments, and collars, and purple raiment that was on the kings of Midian, and beside the chains that were on their camels’ necks.”

Heeren then discusses the Edomites and continues:

“The Greeks include all the nomadic tribes wandering in northern Arabia under the name of Nabataean Arabs. Diodorus, who beautifully describes their way of life, does not forget their caravan trade with Yemen. ‘Not a small part of them,’ he says, ‘makes a business of transporting frankincense, myrrh and other costly spices, which they get from those who bring them from Arabia Felix, to the Mediterranean.’ (Diodorus, II, p.590).

“The riches that some of the desert tribes acquired in this way was great enough to excite the greed of Greek men of war. One of the depots for the wares that went through the district of the Edomites was the fortified place of Petra, from which Northwest Arabia gets the name of Petraean. Demetrius Poliorcetes tried to surprise and plunder this town.” [3]

We must imagine the Israelites during the time of their wanderings as resembling their neighbors the Midianites. It is already reported of Abraham that he was rich not only in cattle but also in silver and gold (Genesis 13, verse 2). The nomadic herdsmen could obtain these only by trade. Their later situation in Canaan could not weaken the trading spirit they had acquired when they were nomads. For the position of this country enabled them to take part in the trade between Phoenicia and Arabia, between Egypt and Babylon, just as before, and to get profit from it, partly by acting as middlemen and forwarders, partly by interfering with it, falling on trading caravans from their mountain fastnesses and plundering them or taking tribute. We must not forget that at that time commerce and robbery were closely related professions.

“Even before the Israelites came to Canaan, the trade of this country was highly developed. In the Tel-el-Amama letters (fifteenth century B.C.) caravans are spoken of as passing through the land under convoy.” [4]

But even by the year 2000 we have evidence of the close commercial relationships between Palestine and Egypt and the lands on the Euphrates.

Jeremias (the Privatdozent at Leipzig, not the Jewish prophet) gives the substance of a papyrus of that period as follows:

“The Bedouin tribes of Palestine were thus closely linked with the civilized land of Egypt. According to the papyrus, their sheikhs occasionally visit the court of the Pharaoh and understand events in Egypt. Ambassadors go with written commissions between the Euphrates region and Egypt. These Asiatic Bedouins are not barbarians at all. The barbarian peoples whom the Egyptian king combatted were expressly distinguished from them. The Bedouin sheiks later allied themselves to wage large campaigns against ‘the princes of the nations.” [5]

Herzfeld, in his Handelsgeschichte der Juden des Altertums, gives an extensive account of the caravan routes that crossed Palestine or passed near it. He is of the opinion that such trade routes were “perhaps of even greater commercial importance in antiquity than the railroads are today.”

“One such route led from Southwestern Arabia parallel to the coast of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Akaba. On it the products of Arabia Felix, Ethiopia and some Ethiopian hinterlands came to Sela, later called Petra, some 70 kilometers south of the Dead Sea. Another caravan route brought the wares of Babylonia and India from Gerrha on the Persian Gulf across Arabia to Petra. From here three other routes diverged: one to Egypt, with forks to the right leading to Arabian ports on the Mediterranean; a second to Gaza, with a very important extension northwards; a third along the eastern shore of the Dead Sea and the Jordan to Damascus. Moreover, Ailat, in the inner corner of the Gulf of Akaba (the ancient Sinus Aelanites) was already a depot for the goods of the countries to the south; it was connected with Petra by a short route. The road north from Gaza, mentioned above, led through the lowlands of Judaea and Samaria, and in the plain of Yisreel ran into another road going to Acco from the east. The wares brought in these diverse ways were put aboard ship in the Arabian Mediterranean ports or in Gaza and Acco, if they were for Phoenicia; for the stretch from Acco to Tyre and Sidon was very rocky and usable for land transport only at a much later date. The much-travelled caravan route from the east led from Babylon on the middle Euphrates through the Arabian-Syrian desert in which Palmyra later flourished, and after a short stretch along the eastern bank of the upper Jordan crossed that river and ran down to the sea through the plain of Yisreel. Shortly before it reached the Jordan, it joined the road from Gilead, which as we have seen was used even in Joseph’s times, and into which ran the road from Gaza; apparently Gaza was also the starting-point of the road from Palestine to Egypt (Genesis 37, verses 25, 41, 57). That these trade routes and the fairs, which formed at their nodal points, had a commercial influence on the Jews cannot be shown from historical facts for some time after this; but on internal grounds cannot be doubted; and by assuming it many an ancient reference is elucidated for the first time.” [6]

Luxury and export industries and art flourished far less than did trade among the Israelites. The reason is probably that they became sedentary at a period when all around them craftsmanship had reached a high point of perfection. Luxury articles were better and cheaper when obtained through trade than when prepared by home industry, which was limited to the production of the simplest goods. Even among the Phoenicians, who became civilized much earlier, the advance of their industry was held back by the competition of Egyptian and Babylonian goods. “In early times the Phoenicians were hardly superior to the inhabitants of the rest of Syria in the field of industry. It is more likely that Herodotus is right when he says that the first Phoenicians that landed on the coasts of Greece were peddling goods that were not produced in their own country, but in Egypt and Assyria, that is the countries inland from Syria. The great cities of Phoenicia first became industrial cities after they had lost their political independence and a large part of their commercial connections.” [7]

It may have been the eternal state of war, too, that interfered with the development of crafts. In any case it is certain that they did not develop very far. The prophet Ezekiel gives a detailed account of the trade of Tyre in his lamentation for that city, including the trade with Israel, whose exports are exclusively agricultural: “Judah, and the land of Israel, they were thy merchants: they traded in thy market wheat of Minnith, and Pannag, and honey, and oil, and balm” (Ezekiel 27, verse 17).

When David made Jerusalem his capital, King Hiram of Tyre sent him “cedar trees, and carpenters, and masons: and they built David an house” (II Samuel, 5, verse 11). The same thing happened when Solomon was building the temple, and paid Hiram twenty thousand measures of wheat and twenty of oil every year.

Without highly developed luxury crafts, that is without artistic handicrafts, there is no fine art in which to portray the human person, going beyond the outline of the human type to individualize and idealize it.

Such an art presupposes a high level of trade to bring the artist all sorts of materials of all sorts of qualities, thus enabling him to choose those best fitted for his purposes. It also presupposes intensive specialization and generations of experience in the handling of the various materials, and finally a high esteem for the artist, which sets him above the level of forced labor and gives him leisure, joy and strength.

All these elements combined are to be found only in large commercial cities with vigorous and well-established handicrafts. In Thebes and Memphis, in Athens, and later, after the Middle Ages, in Florence, Antwerp and Amsterdam, the fine arts reached their high points on the basis of a healthy craftsmanship.

This was lacking among the Jews, and had its effect on their religion.

The Conception of God in Ancient Israel

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]deas about divinity are extremely vague and confused among primitive peoples, and by no means as clear-cut as we see them presented in the mythology books of the learned. The individual deities were not clearly conceived nor distinguished from one another; they are unknown, mysterious personalities affecting nature and men, bringing men good luck and bad luck, but as shadowy and indefinite, at least at first, as visions in a dream.

The only firm distinction of the individual gods one from the other consists in their localization. Every spot that particularly arouses the fantasy of primitive man seems to him to be the seat of a particular god. High mountains or isolated crags, groves in special places and also single giant trees, springs, caves – all thus receive a sort of sanctity as the seats of gods. But also peculiarly shaped stones or pieces of wood may be taken to be the seats of a deity, as sacred objects the possession of which assures the aid of the deity that inhabits them. Every tribe, every clan tried to obtain such a sacred object, or fetish. That was true of the Hebrews as well, for their original idea of God was quite on the level we have just described, far from monotheism. The sacred objects of the Israelites seem to have been nothing more than fetishes at first, from the images or idols (teraphim) that Jacob steals from his father-in-law Laban to the ark of the covenant in which Jehovah is located and which brings victory and rain and riches to the man who possesses it justly. The sacred stones that the Phoenicians and Israelites worshipped bore the name of Bethel, God’s house.

The local gods and the fetishes are not distinctly individual on this stage; often they have the same names, as for example among the Israelites and Phoenicians many gods were called El (plural, Elohim) and others were called by the Phoenicians, Baal, the lord. “Despite the identity of names all these Baals counted as quite distinct beings. Often nothing more was added to distinguish them than the name of the place in which the god in question was worshipped.” [8]

It was possible to keep the separate gods distinct in the minds of the people only when the plastic arts had developed enough to individualise and idealise human forms, to present concrete forms with a character of their own, but also with a charm, a majesty or a size or fearsomeness that raised them above the form of ordinary men. At this point polytheism got a material basis; the invisible became visible and so imaginable by all; now the individual gods were permanently distinguished from each other and confusion among them became impossible. From then on men could choose individual figures out of countless numbers of spiritual beings that danced about in the fantasy of primitive man, and give them particular forms.

We can clearly trace how the number of the particular gods in Egypt increases with the development of the fine arts. In Greece too it is certainly no accident that the highest point of the art industry and human representation in the plastic arts coincided with the greatest diversity and sharpest individualization in the world of the gods.

Because of the backwardness of the industry and art of the Israelites, they never carried to completion the progress of the industrially and artistically developed peoples, the replacement of the fetish, the dwelling place of the spirit or god, by the image of the god. In this respect too they remained on the level of the Bedouin mode of thought. The idea of representing their own gods in pictures or images never came into their heads. All the images of gods they knew were images of foreigners’ gods, gods of the enemy, imported from abroad or imitated after their model; and hence the hate of the patriots against these images.

This had an element of backwardness; but it made it easier for the Jews to advance beyond polytheism once they learned of the philosophical and ethical monotheism that had arisen in various great cities on the highest level of development of the ancient world for causes we have already mentioned. Where the images of the gods had struck root in the minds of the people, polytheism received a firm basis that was not so easily overcome. The indefiniteness of the images of the gods and the identity of their names in different localities on the other hand, opened the way for popularizing the idea of one god, compared to whom all the other invisible spirits are but lower beings.

At any rate it is no mere chance that all the monotheistic popular religions came from nations that were still in the nomadic mode of thought and had not developed any notable industry or art: along with the Jews, these were the Persians and later the Arabians of Islam, who adopted monotheism as soon as they came into contact with a higher urban civilization. Not only Islam but the Zend religion is monotheistic; this recognizes only one lord and creator of the world, Ahuramazdrr. Angronlainju (Ahrimarl) is a subsidiary spirit, like Satan.

It may seem strange that backward elements will adopt an advance more easily and carry it further than more developed elements will; it is a fact, however, that can be traced even in the evolution of organisms. Highly developed forms are often less capable of adaptation and die out more easily, whereas lower forms with less specialized organs can more easily adapt to new conditions and hence be capable of carrying progress further.

In man the organs do not merely develop in an unconscious way; he also develops other artificial organs whose manufacture he can learn from other men. With respect to these artificial forms, individuals or groups can leap over whole stages of development when the higher stage has already been prepared for them by others from whom they can take it over. It is a well-known fact that many farm villages took to electric lighting more easily than the large cities which already had large capital investments in gas lighting. The farm village could jump directly from the oil lamp to electricity without passing through the phase of gas; but only because the technical knowledge required for electric lighting had already been gained in the big cities. The farming village could never have developed this knowledge on its own account. Similarly, monotheism found easier acceptance among the Jews and Persians than among the mass of Egyptians, Babylonians or Hellenes; but the idea of monotheism had first to be developed by the philosophers of these more advanced civilizations.

However at the time with which we are dealing, before the Exile, things had not yet gone so far; the primitive cult of the gods still prevailed.

Trade and Philosophy

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]rade gives rise to a way of thinking different from that based on handicrafts and art.

The specific productive activity that produces specific use values is of interest primarily to the consumer, who wants specific use values. If he needs cloth, he is interested in the labor that goes into making the cloth, precisely because it is this particular cloth-producing work. But for the producer of the commodities as well -and on the stage we are speaking of this includes, as a rule, not only wage workers but independent farmers, craftsmen and artists, and the slaves of any of these – labor enters into the picture as the specific activity that enables him to produce specific products.

It is different with the merchant. His activity consists in buying cheap in order to sell dear. What specific commodities he buys or sells is basically a matter of indifference to him, as long as they find a purchaser. He does have an interest in the quantity of labor socially necessary at the times and places of purchase and of sale to produce the goods he deals in, for that has the decisive influence on their prices, but this labor interests him only as value-giving, general human labor, abstract labor, not as concrete labor producing specific use values. The merchant is not consciously aware of all this; for it is a long time till men come to discover the determination of value by general human labor. The discovery was first completely reached by the genius of a Karl Marx under conditions of highly-developed commodity production. But, many thousands of years before that, abstract general human labor, as contrasted with concrete forms of labor, finds its tangible expression in money [9], which does not need the slightest powers of abstraction to comprehend. Money is the representative of the general human labor contained in every commodity; it does not represent a particular kind of labor, like the work of weavers, potters or blacksmiths, but all and every kind of labor, one kind today and another kind tomorrow. The merchant however is interested in the commodity only as it represents money; he does not care for its specific usefulness but for its specific price.

The producer – peasant, craftsman, artist – is interested in the particular nature of his work, the particular nature of the stuff he has to work on; and he will increase the productivity of his labor power in the measure that he specializes his labor. His specific work ties him down to a specific place, to his land or his workshop. The determinateness of the work that occupies him thus produces a certain narrowness in his way of thinking, which the Greeks called banausic (from banausos, workman). “It may well be that smiths, carpenters and shoemakers are skilled in their trades,” said Socrates in the fifth century B.C., “but most of them are slavish souls; they do not know what is beautiful, good and just.” The same opinion was expressed by the Jew Jesus son of Sirach about 200 B.C. Useful as crafts are, he holds, the craftsman is useless in politics, jurisprudence, or the dissemination of moral education.

Only the machine makes it possible for the mass of the working class to rise above this narrowness, but it is only elimination of capitalist commodity production that will create the conditions under which the machine can fully fulfill its noble mission of freeing the laboring masses.

The activity of the merchant on the other hand has quite a different effect on him. He need not confine himself to the knowledge of a specific branch of production in a specific locality; the wider his view, the more branches of production he takes in, the more regions with their special needs and conditions of production, the sooner he will find out which commodities it is most profitable to deal in at a given time; the sooner he will find the markets where he can buy most profitably and those in which he can sell most profitably. For all the diversity of products and markets he is involved in, basically his interest is only in the relationship of prices, that is the relationships of various quantities of abstract human labor, that is of abstract numerical relationships. The more trade develops, the more buying and selling are separate in space and time, the greater the differences of the coins and coinages the merchant has to deal with, the further apart the acts of selling and payment are and systems of credit and interest develop: the more complex and diversified these numerical relationships become. Thus trade must develop mathematical thinking and, along with that, abstract thinking. As trade broadens horizons beyond local and professional narrow-mindedness and opens up to the merchant knowledge of the most widely differing climates and soils, stages of culture and modes of production, it stimulates him to comparisons, enables him to see what is general in the mass of particulars, what is regular in the mass of fortuities, what always repeats itself under given conditions. In this way, as well as by mathematical thinking, the power of abstraction is highly developed, while handicrafts and art develop the sense for the concrete, but also for the superficial aspects, rather than the essence of things. It is not the “productive” activities like agriculture and handicrafts, but “unproductive” trade that forms those mental capacities that constitute the basis of scientific research.

But that is not to say that trade as such gives rise to research itself. Disinterested thought, the quest for truth rather than for personal advantage, is the last thing to characterize a merchant. A peasant and a craftsman live only by the work of their hands. The well-being they can attain is confined within narrow limits; but within those limits it is assured to every healthy average individual under primitive conditions, if war or natural catastrophes do not ruin the whole community and drive it into poverty. In such cases trying to get beyond the average is neither necessary nor very promising. Cheerful contentment with one’s inherited lot characterizes these occupations, until capital, at first in the form of usury capital, subjugates these occupations or those who practice them.

The success of concrete useful labor, at this stage of industrial development is limited by the powers of the individual; the success of trade has no limits. Trading profit has its limits set only by the quantity of money, of capital, that the trader owns, and this quantity may be expanded without limit. On the other hand this trade is exposed to much greater vicissitudes and dangers than the eternal monotony of peasant and handicraft production in simple commodity production. The merchant is always swinging between the extremes of great wealth and utter ruin. The passion for gain is stimulated to an extent unknown in the productive classes. Insatiable greed and merciless brutality toward competitors and the objects of exploitation – these are the marks of the merchant. This is still seen today in a way that revolts people who work for a living, and especially where the exploitation by capital does not meet with powerful resistance, as in the colonies.

This is not a way of thinking that makes disinterested scientific thought possible. Trade develops the requisite mental traits, but not their application in science. On the contrary, where it influences science its effect is to falsify and twist it to its own ends, a procedure of which bourgeois science today shows countless examples.

Scientific thought could only arise in a class that was influenced by all those traits, experiences and knowledge that trade brought with it, but at the same time was free from the need for earning money and so had time and opportunity for, and joy in unprejudiced research, in solving problems without considering their immediate, practical and personal results. Philosophy developed only in the great commercial centers, but only in those where there were elements outside of commerce who were assured of leisure and freedom by their property or their social position. In many Greek trading cities such elements were the great landowners, who were relieved of work by their slaves and did not live in the country, but in the city, so that they avoided falling into the boorishness of the country squire but felt all the influences of the city and its great commerce.

It would seem however that such a class of landholders, living in the city and philosophizing, appeared only in maritime cities whose land area was large enough to produce such a landed aristocracy, but not large enough to keep them from the city and tie their interests down to extending their land holdings. These conditions are to be seen above all in the Greek maritime cities. The lands of the Phoenician cities by the sea were too small to produce such landed property; everybody lived by trade.

In cities surrounded by extensive territories, the landholders seem to have remained more under the influence of country life, to have developed further toward the mentality of the country squire. In the great inland trading centers of Asia, the group who were most free from working for a living and least engaged in practical activities were the priests of certain shrines. Quite a few of these shrines won importance and wealth enough to maintain permanent priests, whose duties were light enough. The same social task that fell to the share of the aristocracy in the Greek seaside towns was incumbent on the priests of the temples in the great trade centers of the Oriental mainland, in particular Egypt and Babylon: that is, the development of scientific thought, of philosophy. This however set a limit to Oriental thinking from which Greek thought was free: constant connection with and regard for a religious cult. The cult gained what philosophy lost, and the priests gained too. In Greece the priests remained simple officials of the rites, guardians of the shrines and performers of the religious acts there; in the great commercial centres of the Orient they became preservers and administrators of all of knowledge, scientific as well as social, mathematics, astronomy and medicine as well as history and law. Their influence in the state and society was enormously increased by this. Religion itself however was able to attain a spiritual depth of which the Greek mythology was not capable, since Hellenic philosophy soon put this to one side, without trying to fill out its naive intuitions with deeper knowledge, and to reconcile the two.

It is the aloofness of philosophy from the priesthood, along with the flowering of the fine arts, that gives Greek religion its sensual, vivid, joyous, artistic quality. On the other hand, in a region with important international trade but without well-developed plastic arts, without a lay aristocracy with intellectual inclinations and needs, but with a strong priesthood and a religion that had not yet developed a polytheism with clear-cut individual deities, it must have been easier for that religion to take on an abstract, spiritualized character and for the deity to become an idea or a concept rather than a person.

Trade and Nationality

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]rade influences men’s thinking in still another way. It greatly fosters national feeling. We have already mentioned the narrowness of the mental horizon of peasant and petty bourgeois as compared with the broad view of the merchant. He acquires that breadth in the course of his constant pressing forward, away from the place in which the accident of birth had set him. We see this most sharply in maritime nations, like the Phoenicians and Creeks in antiquity; the first ventured far beyond the Mediterranean into the Atlantic Ocean, and the latter opened up the Black Sea. Land commerce did not allow such wide sweeps. And trading by sea presupposed advanced technology, especially in shipbuilding; it was trade between higher and lower peoples, in which the latter could be easily subjugated and colonies founded by the commercial nation. Commerce on land was first and most easily carried on by nomads, who came to more highly developed peoples and there found surpluses of agricultural and industrial products all ready. There could be no question of the founding of colonies by single expeditions. Now and then a number of nomad tribes might get together to plunder or conquer a richer, more advanced country, but in that case too they did not come as colonists, bearing a higher civilization. Such unions of roving tribes occurred seldom, under exceptional circumstances, since the whole nature of nomadic cattle-raising isolates the tribes and clans, and even the single families, from each other and scatters them over vast areas. As a rule, the traders from these tribes could enter into the rich and powerful states with which they traded, only as tolerated refugees.

This applies as well to the traders of the small nations that had settled athwart the international route from Egypt to Syria. Like the Phoenicians and the Creeks they too founded settlements in the countries they traded with, but they were not colonies in the strict sense of the word: they were not powerful cities by means of which a civilized nation dominated and exploited barbarians, but weak communities of refugees within powerful and highly cultivated cities. That made it all the more necessary for the members of these communities to cohere most tightly against the foreigners in whose midst they lived, and gave urgency to their desire for the power and prestige of their nation, since it was on that that their own security and prestige abroad depended, and hence too the conditions under which they carried on their commerce.

As I have remarked in my book on Thomas More, the merchant is, down to the nineteenth century, at once the most international and the most national member of society. In merchants from small nations, exposed without defence to mistreatment in foreign parts, the need for national cohesion and national greatness must have grown especially strong, along with hatred toward the foreigner.

The Israelite traders were in such a position. The Israelites must have been carried off to Egypt early, while they were still wandering herdsmen, long before they became sedentary dwellers in Canaan. Canaanite migrations into Egypt are reported by testimony that may go as far back as the third millennium. Eduard Meyer says on this matter:

“A famous painting in the tomb of Chnemhotep in Benihassan shows us a Bedouin family of 37 people led by their head, Absha, came to Egypt in the sixth year of the reign of Usertesen III. [10] They are described as Amu, that is Canaanites, and their features clearly show them to be Semites. They wear the bright clothes that had been favored in Asia since ancient times, are armed with bow and spear and bring asses and goats with them; one of them is able to play the lyre. As valuables, they brought the eye-pigment meszemuth with them. Now they ask for admission and address themselves to the count of Menachufu, Chnemhotep, to whom the eastern mountain lands are subject. A royal scribe, Neserhotep, brings them before him for further orders and reports to the king. Scenes like the one here immortalized must have taken place often, and doubtless many Canaanite traders and craftsmen must have settled in the eastern cities of the delta in this way, and there we find them in later times. Conversely it is certain that Egyptian traders often came to Syrian cities. Even though with many intermediary links, Egyptian commerce by this time must have extended as far as Babylon.”

Some hundreds of years later, perhaps around the year 1800 B.C., at a time when Egyptian society was in decline, North Egypt was conquered by the Hyksos, undoubtedly Canaanite nomad tribes, whom the weakness of the Egyptian government tempted, and enabled, to invade the rich Nile country, where they maintained themselves for over two hundred years. “The significance of the Hyksos’ rule in world history is that by means of it there arose a lively intercourse between Egypt and the Syrian regions which was never interrupted thereafter. Canaanite merchants and artisans came in droves to Egypt; we find Canaanite personal names and cults at every step in the new kingdom; Canaanite words begin to penetrate into Egyptian. How lively the communication was is shown by the fact that a medical work written about the year 1550 B.C. contains a prescription for the eyes prepared by a certain Amu of Kepni, which is very probably the Phoenician city of Byblos.” [11]

We have no reason to assume that among the Amu, the Semitic Bedouins and city folk east and northeast of Egypt, there were not Hebrews too, although they are not specifically mentioned. On the other hand it is hard to make out today what we should take to be the historical core in the legends of Joseph, the stay of the Hebrews in Egypt and their exodus under Moses. Equating them to the Hyksos, as Josephus does, is untenable. This much does seem to follow, that, if not all of Israel, at least single families and caravans of Hebrews early came to Egypt, where they were treated more or less well according to changing situations there, gladly received at some times and later harried and hunted as “burdensome” foreigners. That is the typical fate of such settlements of foreign traders from weak nations in powerful empires.

The “Diaspora”, the scattering of the Jews over the world, does not in any case begin for the first time with the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans, nor even with the Babylonian exile, but much earlier; it is a natural consequence of trade, a phenomenon shared by the Jews in common with most commercial peoples. But of course agriculture remained the principal source of the livelihood of the Jews down to the time of the exile, as it did with most of these peoples. Previously commerce had been only a secondary occupation for the nomadic herdsmen. When they became sedentary and the division of labor appeared, the roving merchant and the peasant were differentiated; but the number of merchants was relatively small, and the peasant determined the character of the people. The number of Israelites living abroad was small in any case compared to the number of those who remained at home. In all this the Jews did not differ from other nations.

But they lived in conditions in which the hatred of foreigners and strong national feeling, even sensitiveness, which had arisen among the merchants, were transmitted to the mass of the people to a greater extent than was the case with the general run of peasant peoples.

Canaan, Road of the Nations

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]e have seen the importance of Palestine for the commerce of Egypt, Babylonia and Syria. From time out of mind these states had endeavored to get the country into their hands.

In the struggle against the Hyksos (about 1800 to 1530 B.C.), a military spirit had arisen in Egypt; at the same time the Hyksos had greatly furthered communication between Egypt and Syria. After the expulsion of the Hyksos, the Egyptians turned to military expansion, above all in the direction of controlling the commercial route to Babylonia. They forced their way as far as the Euphrates, occupying Palestine and Syria. They were soon driven out of Syria by the Hittites; in Palestine they held out longer, from the fifteenth down to the twelfth century. There too they garrisoned a series of fortresses overawing the country, including Jerusalem.

Finally the military power of Egypt weakened, and from the twelfth century on it could no longer hold Palestine; at the same time the Syrian Hittites were weakened because their southward pressure was brought to a halt by the incipient expansion of the Assyrians.

In this way the foreign domination of Palestine was broken. A group of Bedouin tribes, assembled under the name of Israelites, made use of the opportunity to break into the country and gradually conquer and occupy it. They had not yet finished the enterprise, and were still in fierce battle with the former inhabitants of the country, when new enemies arose in the shape of other Bedouin tribes pushing after them into the “promised land”. At the same time they clashed head on with an opponent, the inhabitants of the plain between the highlands occupied by the Jews, and the sea. These were the Philistines. They must have felt themselves desperately menaced by the aggression of so warlike a people as the Israelites. On the other hand, the coastal plain must have been particularly attractive to the Israelites, for through it went the high road linking Egypt with the north. Whoever controlled it also had control of almost the entire external trade of Egypt with the north and the east. The sea-borne trade of Egypt on the Mediterranean was still very small at that time. If the inhabitants of the mountain ranges that ran along the plain were warlike and predatory clans, they would constitute a constant threat to commerce to and from Egypt, and to the riches derived from it. And they were warlike and predatory. We are often told of the formation of robber bands in Israel, by Jephtha for example, “and there were gathered vain men to Jephtha, and went out with him,” (Judges 11, verse 3). Robber raids into the land of the Philistines are often spoken of. In the case of Samson, “the Spirit of the Lord came upon him, and he went down to Ashkelon, and slew thirty men of them, and took their spoil” to pay a lost bet (Judges 14, verse 19). David is shown beginning as the leader of a robber band, “and every one that was in distress, and every one that was in debt, and every one that was discontented, gathered themselves unto him; and he became a captain over them; and there were with him about four hundred men” (I Samuel 22, verse 2).

It is no wonder that there was an almost continuous feud between the Philistines and the Jews, and that the former did everything in their power to tame their troublesome neighbors. Hard-pressed on one side by the Bedouins and on the other by the Philistines, Israel sank into dependence and distress. It succumbed to the Philistines the more easily because living in the hills favored cantonal spirit and split up the tribes, whereas living in the plain helped the various tribes and communities of the Philistines to unite for action. It was only after the strong warrior king David succeeded in welding the different tribes of Israel into a firm unity that this tribulation came to an end.

Now the Philistines were overthrown and the last strong cities in Canaan that had still resisted Israel were taken, including Jerusalem, an unusually strong and defensible place, that resisted the Israelites the longest and controlled the approaches into Palestine from the south. It became the capital of the kingdom and the seat of the fetish of the union, the ark of the covenant, in which the war god Jahveh dwelt.

David now won domination over the entire trade between Egypt and the north, and great gains came to him from it, which enabled him to increase his military power and extend the frontiers of his state to the north and the south. He overcame the plundering Bedouin tribes as far as the Red Sea, made the trade routes thither safe, and with the help of the Phoenicians, for the Israelites knew nothing of sea-faring, began to carry on, on the Red Sea the commerce that had previously gone by land north from Southern Arabia (Saba). This was Israel’s golden age, and it achieved a dazzling fullness of power and wealth from its position dominating the most important trade routes of its time.

And yet it was precisely this position that was its ruin. Its commercial importance was not a secret to the great neighbor states. The more the country flourished under David and Solomon, the more it must have aroused the greed of its neighbors, whose military power was on the increase again just at this time; in Egypt, in particular, because of the replacement of the peasant militia by mercenaries, who were more easily made ready for wars of aggression. It is true the power of Egypt was no longer adequate to the task of permanently conquering Israel: that was so much the worse for Israel. Instead of becoming permanently tributary to a great state whose power would at least have brought it peace and protection from foreign enemies, it became the bone of contention between Egyptians and Syrians, and later of Assyrians as well; Palestine was the battlefield on which these powers clashed. To the devastations of the wars it had to wage in its own interests there were added the devastations of the great armies that now fought there for interests that were entirely alien to the inhabitants of the country. And the burdens of tribute and dependency that were imposed on the Israelites from time to time now were none the easier for the fact that it was not always the same master who imposed them, that their master changed with the fortunes of war, each one holding it as a precarious possession out of which he wanted to get as much as possible as quickly as possible.

Palestine was in a situation at that time much like that of Poland in the eighteenth century or Italy, especially Northern Italy, from the Middle Ages on down to the nineteenth century. Like Palestine then, Italy and Poland later found themselves unable to carry on a policy of their own, and constituted the theatre of war and the object of plunder for foreign great powers: Poland for Russia, Prussia and Austria; Italy for Spain and France, along with the master of the German Empire, later Austria. And as in Italy and Poland, a national splintering took place in Palestine too, and for similar reasons: In Palestine, as in Italy, the various sections of the country were influenced by their neighbors in different ways. The northern part of the region occupied by the Israelites was most threatened, and also dominated, by the Syrians and then by the Assyrians. The southern part, Jerusalem with its surroundings, essentially the district of the tribe of Judah, was more threatened by Egypt or dependent on it, according to circumstances. Israel proper therefore often seemed to require different policies than Judah did. This difference in foreign policies was the principal cause for Israel’s splitting up into two kingdoms, in contrast with the prior situation, when foreign policy had constituted the reason for uniting the twelve tribes against the common enemy, the Philistines.

But the similar situation must have evoked similar effects in Palestine as in Italy and Poland in still another respect: here as well as there we meet with the same national chauvinism, the same national sensitiveness, the same xenophobia, going beyond the measure of what national enmities produced in the other peoples of the same era. And this chauvinism was bound to increase the longer this intolerable situation lasted, making the country constantly a football of fate and a battleground for the robber incursions of its great neighbors.

Given the importance that religion had in the Orient, for reasons to which we have referred, chauvinism had to appear in religion too. The vigorous trade relations with neighboring countries brought their religious ideas, cults and images into the land. Hatred of the foreigner had more and more to become hatred of his gods, not because their existence was questioned, but just because they were regarded as the most effective helpers of the enemy.

This does not distinguish the Hebrews from the other peoples of the Orient. The tribal god of the Hyksos in Egypt was Sutekh. When the Hyksos were driven out, their tribal god had to give way too; he was identified with the god of darkness, Seth or Sutekh, from whom the Egyptians turned with horror.

The patriots of Israel and their leaders, the prophets, must have turned against the strange gods with the same fury that the German patriots at the time of Napoleon turned against French fashions and French words in the German language.

Class Struggles in Israel

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he patriots however could not long be satisfied with xenophobia alone. They were moved to regenerate the state and give it greater strength. Social decomposition increased in the Israelite community in proportion to the external pressure. The growth of trade since David’s time had brought great wealth into the land, but, as elsewhere in antiquity, agriculture remained the basis of society and landholding the surest and most honorable form of property. Just as elsewhere, elements that had become wealthy tried to own land or to increase their holdings if they were already landowners. Here too the tendency to form latifundia appeared. This was made easier by the fact that in Palestine, as elsewhere, the peasant was ruined under the new conditions. Previously the struggles of the Israelites had been little local feuds fur the most part, which did not take the peasant militiaman far from his soil or keep him away long; but it was no longer so once Israel was a more important state and was involved in the wars of the great powers. Military service now ruined the peasant anti made him dependent on his moneyed and influential neighbor, who became a usurer, with the choice of driving him from his little farm or leaving him there, only as a debt slave obliged to work out his debt. The latter method must often have been preferred, for we do not hear much of purchased slaves of other nationalities in Palestine. If slaves by purchase are to be anything more than a costly luxury in the house, if they are to be a profitable investment in production, they presuppose constant successful wars which provide abundant cheap slave material. This was out of the question for the Israelites. For the most part they belonged to those unfortunate peoples that furnished slaves rather than acquired them. All this must have led the owners of the latifundia, who needed cheap and dependent labor forces, to prefer the debt slavery of their own countrymen, a system that has been preferred elsewhere, as for example in Russia after the abolition of serfdom, when the great landowners lack slaves or serfs.

As a result of this process, there was a serious reduction in the military power of Israel and its ability to stand up against external enemies, together with a reduction in the number of free peasants. The patriots and social reformers and friends of the people united to call a halt to this fatal development. They called the people and the kingdom to battle against the strange gods and the enemies of the peasant within the land. They prophesied the fall of the state if it was not able to put an end to the oppression and impoverishment of the peasantry.

“Woe unto them,” Isaiah cried, “that join house to house, that lay field to field, till there be no place, that they may be placed alone in the midst of the earth? In mine ears said the Lord of hosts, Of a truth many houses shall be desolate, even great and fair, without inhabitant” (5, verses 8 and 9).

And the prophet Amos predicted, “Hear this word, ye kine of Bashan, that are in the mountain of Samaria, which oppress the poor, which crush the needy, which say to their masters, ‘Bring, and let us drink.’ The Lord God hath sworn by his holiness, that, lo, the days shall come upon you, that he will take you away with hooks, and your posterity with fishhooks” (4, verses 1 and 2).

“Hear this, O ye that swallow up the needy, even to make the poor of the land to fail, saying, When will the new moon be gone, that we may sell corn, and the sabbath, that we may set forth wheat, making the ephah small, and the shekel great, and falsifying the balances by deceit? That we may buy the poor for silver, and the needy for a pair of shoes; yea, and sell the refuse of the wheat? The Lord hath sworn by the excellency of Jacob, Surely I will never forget any of their works. Shall not the land tremble for this, and every one mourn that dwelleth therein?” (Amos 8, verses 4 to 8).

“It can be clearly seen from the continual complaints of the prophets against existing law that the wealthy and mighty made use of the government apparatus to give legal sanction to the new order of things: ‘Woe unto them that decree unrighteous decrees,’ says the eloquent Isaiah, ‘... to turn away the needy from judgment, and to take away the right from the poor of my people’ (10, verses 1 and 2). ‘Zion shall be redeemed with judgment’ (ibid. 1, verse 27). ‘The pen of the scribes is in vain’ (Jeremiah 8, verse 8). ‘For ye have turned judgment into gall, and the fruit of righteousness into hemlock’ (Amos 8, verse 12).” [12]

It was lucky for the prophets that they did not live in Prussia or Saxony! They would never have escaped prosecution for sedition, libel and high treason.

But no matter how forceful their agitation was, or how urgent the needs from which it arose, they could not succeed, even though they might now and then obtain legislation for easing poverty or ironing out social contradictions. Their efforts could tend only to restore the past and dam up the stream of economic development. This was impossible, as were the similar efforts of the Gracchi in Rome. The fall of the peasantry and hence of the state was as irresistible in Israel as it was later in Rome. But the fall of the state was not such a slow death in Israel as it was in the world empire of Rome. Overwhelmingly powerful opponents put a sudden end to it long before its vitality was exhausted. These opponents were the Assyrians and the Babylonians.

The Decline of Israel

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]rom Tiglath-Pileser I on (about 1115-1050 B.C.), With occasional interruptions, the Assyrians begin their policy of conquest on the grand scale which brought them closer and closer to Canaan. These powerful conquerors introduced a new method in handling the vanquished which had a devastating effect on the Israelites.

During their nomad period, the whole people had an interest in a military adventure, for every member of the nation profited from it. The expedition ended either with the plunder of a rich country or with its conquest, in which case the victors settled there as aristocratic exploiters of the native masses.

On the sedentary agricultural stage the mass of the population, the peasants and craftsmen, no longer had any interest in a war of conquest, but increased interest in a successful defensive war, for in case of defeat they faced the loss of their freedom and that of their country. A forcible policy of outward expansion was desired by the masters of commerce, who needed protection of trade routes and foreign markets, something that usually could be assured only by military occupation of at least a few points. The landed aristocracy also pressed for territorial expansion, being always hungry for more land and new slaves, and the kings too were warlike in feeling, smelling increased tax yields.

So long however as there was no standing army, and no bureaucracy detached from the land and free to be installed anywhere, the permanent occupation and administration of a conquered land by a victor was hardly possible at this stage. What he usually did was, after a thoroughgoing plundering and weakening of the subdued nation, to exact an oath of loyalty and fix tribute payments, leaving the ruling classes of the country in their positions and changing nothing in its political constitution.

This had the disadvantage that the vanquished took the first opportunity to shake off the hated yoke, so that a new military expedition was necessary to overcome them again, accompanied of course with the most barbarous punishment of the “rebellion”.

The Assyrians hit upon a system that promised greater permanence to their conquests: where they encountered stubborn resistance or experienced repeated rebellions, they crippled the nation by taking away its head, that is by stealing the ruling classes, by exiling the noblest, richest, most intelligent and warlike inhabitants, particularly of the capital, to a distant region, where the deportees were completely powerless without the lower stratum of ruled-over classes. The peasants and small handicraftsmen who were left behind now constituted a disconnected mass incapable of any armed resistance to the conquerors.

Shalmaneser II (859 to 825 B.C.) was the first Assyrian king to invade Syria proper (Aleppo, Hamath, Damascus), and also the first who gives us tidings of Israel. In a cuneiform report of the year 842 he mentions among other things a tribute of the Israelite king Jehu. This forwarding of tribute is illustrated; it is the oldest representation of Israelite figures that has come down to us. From that time on Israel came into ever closer contact with Assyria, paying tribute or rising up in rebellion, while the practice of transplanting the upper layer of the conquered, and especially of rebellious, peoples kept spreading. It was now but a question of time when at the hands of the unconquered and apparently unconquerable Assyrians the day of destruction would come for Israel too. No great gift of prophecy was required to foresee this end, which the Jewish prophets so vividly foretold.

For the northern kingdom the end came under King Hosea, who in 724 refused to pay the tribute to Assyria, relying on help from Egypt; but the help did not come. Shalmaneser IV marched on Israel, beat Hoses, took him prisoner and besieged his capital, Samaria, which was taken by Shalmaneser’s successor Sargon in 722 after a three-year siege. The “flower of the population” (Wellhausen), 27,290 men by Assyrian accounts, were now removed to Assyrian and Median cities. In their stead the king of Assyria brought people from rebellious Babylonian cities “and placed them in the cities of Samaria instead of the children of Israel; and they possessed Samaria, and dwelt in the cities thereof” (II Kings 17, verse 24).

Thus, it was not the entire population of the northerly ten tribes of Israel that was carried off, but only the most noble from the cities, which were resettled by foreigners. But that was enough to begin the end of the nationality of these ten tribes. The peasant is not capable by himself of building up a community apart. The Israelite city-dwellers and aristocrats who were transplanted to Assyria disappeared into their new surroundings in the course of generations.

The First Destruction of Jerusalem

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]f the people of Israel, only Jerusalem was left with its surrounding district, Judah. It seemed that this little residue would soon share the fate of the large mass and the name of Israel thus disappear front the face of the earth. But it was not to be the lot of the Assyrians to take and destroy Jerusalem.

It is true that the army of the Assyrian Sennacherib that was marching on Jerusalem (701) was compelled to return home by disorders in Babylon, and Jerusalem was saved; but that was only a reprieve. Judah remained an Assyrian vassal state, which could be snuffed out at any moment.

But from Sennacherib’s time on the attention of the Assyrians was more and more drawn to the north, where warlike nomads were increasing their pressure, and more and more force was required to repel them: Cimmerians, Medes, Scythians. About 625 the last named broke into the Near East, plundering and devastating up to the borders of Egypt, but finally left again after 28 years without founding an empire of their own. They did not disappear, however, without leaving marked traces behind them. Their attack shook the Assyrian monarchy to its foundations. The Medes were now able to attack it with more success, Babylon broke away and liberated itself, while the Egyptians took advantage of the situation to bring Palestine under their sovereignty. Josiah, king of Judah, was defeated and killed by the Egyptians at Megiddo (609), after which Necho, the Egyptian king, set up Jehoiakim in Jerusalem as his vassal. Finally in 606 Nineveh was destroyed by the combined Babylonians and Medes. The empire of the Assyrians had come to an end.

That however did not save Judah by any means. Babylon now followed in the footsteps of Assyria and at once tried to get control of the road to Egypt. In the process the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar clashed with Necho, who had penetrated as far as Northern Syria. In the battle at Carchemish the Egyptians were defeated and soon thereafter Judah was made a Babylonian vassal state. We see how Judah was handed from one to another, having lost all independence. Goaded on by Egypt, it refused to pay its tribute to Babylonia in 597· The rebellion collapsed almost without a struggle. Jerusalem was besieged by Nebuchadnezzar and surrendered unconditionally.

“And Nebuchadnezzar came against the city, and his servants did besiege it. And Jehoiachin the king of Judah went out to the king of Babylon, he, and his mother, and his servants, and his princes, and his officers: and the king of Babylon took him in the eighth year of his reign. And he carried out thence all the treasures of the house of the Lord, and the treasures of the king’s house, and cut in pieces all the vessels of gold which Solomon king of Israel had made in the temple of the Lord, as the Lord had said. And he carried away all Jerusalem, and all the princes, and all the mighty men of valeur, even ten thousand captives, and all the craftsmen and smiths: none remained, save the poorest sort of people of the land. And he carried away Jehoiachin to Babylon, and the king’s mother, and the king’s wives, and his officers, and the mighty of the land, those carried he into captivity from Jerusalem to Babylon. And all the men of might, even seven thousand, and craftsmen and smiths a thousand, all that were strong and apt for war” (II Kings 24, verses 11 to 16).

Thus Babylon continued the old method of Assyria; but here too it was not the whole people that was deported, but only the royal court, the aristocrats, the military men and the propertied city dwellers, 10,000 men in all. The “poorest sort of people of the land,” and of the cities as well, stayed behind, and along with them a part of the ruling classes too. Judah was not exterminated. A new king was assigned to it by the lords of Babylon. But now the old game was repeated once more, for the last time. The Egyptians instigated the new king, Zedekiah, to desert Babylon.

Thereupon Nebuchadnezzar laid siege to Jerusalem, took it and put an end (586) to the unruly city that was so disturbing because of its dominant position on the great route from Babylon to Egypt.