A book review by Gaither Stewart

First published on DECEMBER 28, 2007

Celebrating el “Día de los Muertos.” Mexicans do no look upon death the way Americans do; they regard it as a natural event, part of the ineffable continuity of all life.

John Mason Hart. Empire and Revolution: The Americans in Mexico since the Civil War. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. 2002. Pp. xi, 677. $39.95.

The great muralist Diego Rivera could not fail to pay homage to his country's traditions, among which, el Dia de los Muertos, ranks at the very top. (Please click on image: La Calavera Catrina (Catrina Skeleton) with Jose Guadalupe Posada, Librado Rivera, a police officer, Joaquin de la Cantolla y Rico, The Revoltosa, Porfirio Diaz and General Medallas, on her left, and Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, the poet Jose Marti and Porfirio Diaz's wives on her right, central section of the Dream of a Sunday afternoon in Alameda Central Park, 1946-1947.)

The great muralist Diego Rivera could not fail to pay homage to his country's traditions, among which, el Dia de los Muertos, ranks at the very top. (Please click on image: La Calavera Catrina (Catrina Skeleton) with Jose Guadalupe Posada, Librado Rivera, a police officer, Joaquin de la Cantolla y Rico, The Revoltosa, Porfirio Diaz and General Medallas, on her left, and Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, the poet Jose Marti and Porfirio Diaz's wives on her right, central section of the Dream of a Sunday afternoon in Alameda Central Park, 1946-1947.)

MOST CERTAINLY the fifteen months I spent in Mexico several years ago deepened and consolidated my anti-imperialist convictions. Coming to Mexico from Europe I had to step backwards, far away from what I once was and where I stood before in order to see the reality of the new world around me. Or maybe what took place in me in Mexico happened simply because you don’t really need to live very long south of the Rio Grande in order to begin to see imperialism at work. It is clear as day even for the most obtuse: the economic disparity between north and south quickly hits you over the head.

Why are things the way they are? You come to understand that powerful evil forces must be at work if millions of Mexicans are compelled to sneak into the United States and live a dog’s life just to eat. Though it is true that because of the missing social idea America’s poor are poorer than Europe’s poor, Mexico’s poor are much poorer still. Their poverty makes them seem to grovel for sustenance. And all this just across the Rio Grande!

Mexicans do not work on the skyscrapers of Dallas and New York City and wash dishes in cafeterias in Atlanta and in North Carolina or pick fruit in California because they are enamored with Yankee life. They are north of that formidable border with its growing wall for the simple reason that though man does not live by bread alone, he must eat to live. For anyone with eyes to see it is evident that something is startlingly and tragically out of whack in North America.

Exquisite homage to Dia de los Muertos by Rivera's legendary spouse Frida Kahlo. (Click on image!)

Contrary to what some smug pseudo-sociologists and self-made capitalists pontificate, Mexicans do not choose to be poor. Otherwise why the perilous nocturnal crossings over the Rio Grande, risking drowning, betrayals by the same bandits who organize their passage, beatings and arrest by the Texas Rangers, and now if President Bush gets his way being shot down by military reservists along the America’s Berlin style Wall-a Wall to keep Mexicans out, they say, but soon maybe also to keep Americans in.

The old saying about Mexico’s ills still holds: Pobre Mexico tan lejos de dios y tan cerca de los Estados Unidos. Poor Mexico, so far from God and so near the United States. For there is no better place than Mexico to see first-hand the negative results of the pact between American capitalism and the tiny “have” class of Mexican society that has exploited the country’s hard working people for one hundred and fifty years.

The infamous Wall, the near victory of the Left opposition in last year’s disputed elections in Mexico, and the spreading world revolt against American imperialism prompted me to take another look at John Mason Hart’s monumental Empire and Revolution (University of California Press, Berkeley, 2002). Professor Hart’s book answers the question many Americans are asking today: “Why do they hate us so much?” At the outset Professor Hart, University of Houston, quotes a passage from Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes’ masterpiece, The Death of Artemio Cruz, the gist of which is that one cannot commit what North Americans [and the Mexican elite] have committed against Mexico and expect to be loved. Hart sees the historical attitudes of the United States toward its southern neighbor as the model for America’s drive for world hegemony. It was there that the historic compulsion of certain American elites toward external wealth and global power was first expressed.

“From the beginnings of the nineteenth century until the present era, the citizens of the United States attempted to export their unique “American dream” to Mexico. Their vision incorporated social mobility, Protestant values, a capitalist free market, a consumer culture, and a democracy of elected representation…The evolving pattern of American behavior in Mexico has reflected and usually anticipated the interactions of U.S. citizens in other Latin American and Third World societies.” [Editor's note: Of course, none of these supposedly wonderful virtues are real or effective in the United States itself, which has not seen actual democracy practically since its inception, as mechanistic elections guarantee nothing. So the "American Dream"—even when just used as quote—must be defined as an imposture, a self-conscious propaganda meme cynically used by the ruling elites controlling the American nation.—PG)

Hart traces from its origins the role of America’s economic-financial elite in Mexico, for whom annexation has been the traditional goal. Many Americans have favored outright political annexation of parts or of all of Mexico. Many have considered it just a question of time. If one is amazed by the number of Mexicans immigrating to the United States today, Professor Hart reminds us of the mass immigrations of Americans to Mexico in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when Americans purchased large tracts of land in Mexico and immigrated there in increasing numbers. By 1910, 40,000 Americans had swarmed into the new frontier territories-12, 000 in Mexico City itself-where rich Americans settled in the plush Las Lomas quarter of the capital.

Foreigners in that period came to own thirty-five per cent of Mexico. Many opened bars and nightclubs, dance halls, bordellos and casinos-as later in Cuba-rather than investing in agriculture and industry. Thus, early on many became exploiters of the common people.

Hart documents how privatization and foreign investment policies of the regime of Porfirio Diaz in Mexico City from the latter part of the nineteenth century up to the Revolution in 1910 enriched the oligarchy but left little for the people. The Mexican elite and North American capitalists took all. Foreigners had all the benefits and power.

Hart documents how privatization and foreign investment policies of the regime of Porfirio Diaz in Mexico City from the latter part of the nineteenth century up to the Revolution in 1910 enriched the oligarchy but left little for the people. The Mexican elite and North American capitalists took all. Foreigners had all the benefits and power.

At the same time, American financiers and industrialists in Mexico were reaching out greedily and gaining influence in Central America and the Caribbean, and participated together with their British partners in South America, Africa and Asia. Thus, when the Mexican Revolution exploded, the people’s ire was directed against both the Diaz regime and foreign capitalists-chiefly Americans. Their shouts of “Long Live Mexico” and “Death to the Yankees” are echoed today in protests ringing out from Afghanistan and Iraq to Africa to the Middle East. Mexican rioters attacked American targets as do Islamic terrorists today. When the revolutionary Emiliano Zapata proclaimed that the rich of Mexico City treated their horses better than the people, he attracted poor peasants all over Mexico. The Mexican government (and Washington too) has never ceased to fear the Zapatistas, as the movement for “tierra y libertad” (land and freedom) is still called today, and who periodically march on the capital to demand their rights.

Empire and Revolution shows how American-Mexican relations anticipated the issue of globalization (read: US world hegemony) that emerged in the 1990s. Now, globalization, the division of wealth and the economic disparity between the United States and the Third World are sharpening the conflictual relationship between the rich and the poor worlds.

Mexico City is no longer the comfortable old city one recalls from the cinema. Though Mexico City seems familiar, it is another world. The rhythm is different—traffic, noises, the masses on the streets, the way people move, the park of the Alamos, the arcades, the sudden vistas, the Italian style palazzos. Still, though it appears as the Old World in the New, there’s something more peculiar in the air. The city has something universal about it that you don’t feel, let’s say, in ephemeral Detroit, something it would never occur to any sane person to search for in the city of the automobile.

For despite their poverty Mexicans are the first to say: “Not by bread alone.” Earthly bread is necessary but not enough for a man. Universality seems to reside in the Mexican people. That is what one senses in the air. Still, it is strange to the North American that just south of the Rio Grande everything changes. Mexico’s Nobel writer, Octavio Paz, was obsessed with the differences between Mexicans and their North American neighbors:

“Mexicans lie out of fantasy, desperation, or to conquer the squalor of their lives; they (North Americans) don’t lie about the true truth that is always unpleasant but about social truth. North Americans want to understand; we to contemplate. Americans are credulous; we believers. We, as their forefathers, believe that sin and death constitute the foundation of human nature.”

Despite the high percentage of Indios in Mexico, one is tempted to conclude that the Mexican is more European. But it is not that either. The nature of the Mexican makes one wonder if it is positive to be so universal that you can accept anything philosophically? For their universality has not brought great fortune to Mexico! No more than has its proximity to the USA. It seems that only still more ancient peoples like, for example, Sicilians or Sardinians are capable of being simply men. Men who don’t strive for perfection. Perhaps men who just lead good lives are universal without even

realizing it. It makes them free, but at the same time vulnerable to the claws of the hawks.

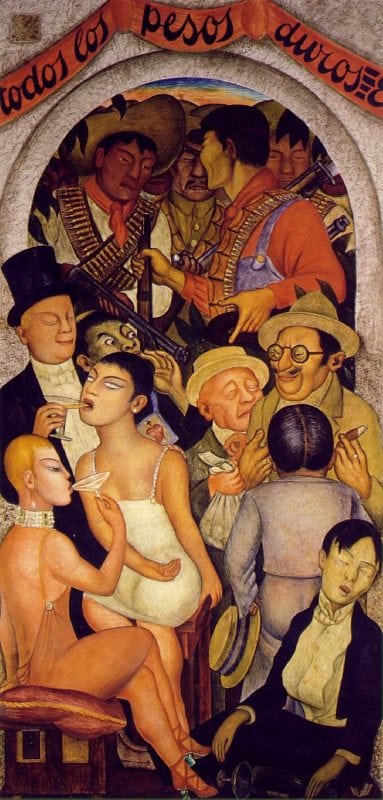

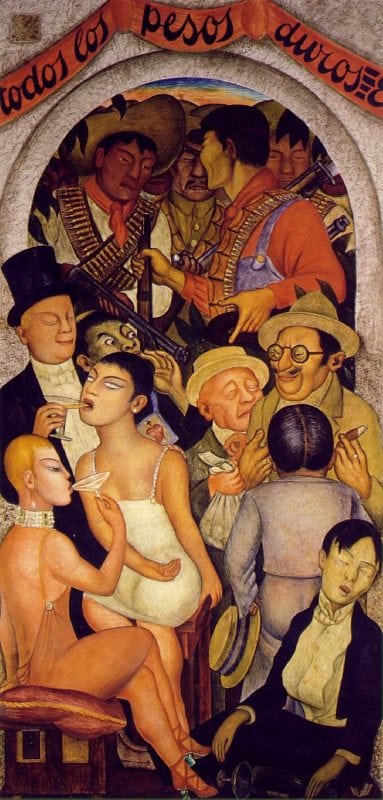

The rich painting the town red and whoring it up in Rivera's scathing vision of the Mexican bourgeoisie, accomplices of imperialist designs in their own country. "Los vendepatrias".

Most of all I have wanted to know who these Mexicans are who make their highlands another world from the rest of North America. In his El Laberinto de la Soledad, Octavio Paz explains that just as behind the Greeks stood the Egyptians or behind the Romans stood the Etruscans or behind the Russians, the Varangians and Mongols, behind the Aztecs and the Spanish conquerors who formed today’s Mexicans there stand millennia of peoples in a long and crazy past.

Maybe because of its solitude on its highlands and in its jungles or because of those ancient origins, Mexico seems to be a tragic country. Rich in an ancient culture and also as you see on Mexico City’s eighty-kilometer long Avenida Insurgentes at the vanguard of modernity, Mexico is however a political caveman. A modern dictatorship based on corruption and retention of power bolstered by American imperialism.

Yet, somehow Mexico is not decadent. It is a viable society, on its way up.

Gaither Stewart

Rome

JOHN MASON HART IS THE JOHN AND REBECCA MOORES PROFESSOR OF HISTORY AND ONE OF THE NATION’S FOREMOST SCHOLARS ON MEXICAN HISTORY. FOR MORE THAN THIRTY-FIVE YEARS HART HAS EXPLORED MULTIPLE ASPECTS OF THE INFLUENCE OF THE UNITED STATES IN MEXICO, THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION, MEXICAN AND MEXICAN-AMERICAN LABOR, AND THE WORKING CLASS OF MEXICO. HART RECEIVED HIS PH.D. IN LATIN AMERICAN HISTORY FROM UCLA IN 1970 AND HAS TAUGHT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON SINCE 1973. HE HAS BEEN THE RECIPIENT OF THE FACULTY EXCELLENCE AWARD AND HELD POSITIONS AS INTERIM AND ASSOCIATE CHAIR OF THE HISTORY DEPARTMENT.

GAITHER STEWART Senior Editor, European Correspondent } Gaither Stewart serves as The Greanville Post European correspondent, Special Editor for Eastern European developments, and general literary and cultural affairs correspondent. A retired journalist, his latest book is the essay asnthology BABYLON FALLING (Punto Press, 2017). He’s also the author of several other books, including the celebrated Europe Trilogy (The Trojan Spy, Lily Pad Roll and Time of Exile), all of which have also been published by Punto Press. These are thrillers that have been compared to the best of John le Carré, focusing on the work of Western intelligence services, the stealthy strategy of tension, and the gradual encirclement of Russia, a topic of compelling relevance in our time. He makes his home in Rome, with wife Milena. Gaither can be contacted at gaithers@greanvillepost.com. His latest assignment is as Counseling Editor with the Russia Desk. His articles on TGP can be found here.

GAITHER STEWART Senior Editor, European Correspondent } Gaither Stewart serves as The Greanville Post European correspondent, Special Editor for Eastern European developments, and general literary and cultural affairs correspondent. A retired journalist, his latest book is the essay asnthology BABYLON FALLING (Punto Press, 2017). He’s also the author of several other books, including the celebrated Europe Trilogy (The Trojan Spy, Lily Pad Roll and Time of Exile), all of which have also been published by Punto Press. These are thrillers that have been compared to the best of John le Carré, focusing on the work of Western intelligence services, the stealthy strategy of tension, and the gradual encirclement of Russia, a topic of compelling relevance in our time. He makes his home in Rome, with wife Milena. Gaither can be contacted at gaithers@greanvillepost.com. His latest assignment is as Counseling Editor with the Russia Desk. His articles on TGP can be found here.

Parting shot—a word from the editors

Parting shot—a word from the editors