By Joanne Laurier, wsws.org

[dropcap]R[/dropcap]obin Williams: Come Inside My Mind is an HBO feature documentary directed by Marina Zenovich (Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, 2008). The film opens with a voice-over by Williams over a blackened screen: “Ladies and gentlemen, it’s time to pump neurons, we are about to enter the domain of the human mind.”

For the next 99 minutes, Zenovich attempts to live up to that promise—or forewarning. She succeeds for the most part, but the task of placing this particular mind in its broader context proves more difficult.

Robin Williams (1951–2014) was an exceptional comic whose ability to create personalities and move among them seemed at times almost supernatural. He contained within himself an apparently infinite number of human types.

Robin Williams (1951–2014) was an exceptional comic whose ability to create personalities and move among them seemed at times almost supernatural. He contained within himself an apparently infinite number of human types.

His career spanned nearly four decades, from the late 1970s until his death four years ago. This was a tumultuous period, but not an easy one for artists. For historical and ideological reasons, its immense contradictions were not readily accessible even to sensitive artists.

It is disappointing, but not surprising, that Zenovich shies away from the complexities of the epoch, including the ones that must have helped undermine Williams’ psychological state. As the WSWS wrote at the time of his death: “One cannot avoid the conclusion that an artist of Robin Williams’ caliber was especially vulnerable to the blows delivered relentlessly by the existing social setup—with its endless glorification of all that is base and rotten (that is, its adulation of the rich and their values)—to a human being’s innate sense of decency. The fate of Robin Williams’—for all its poignancy—is a highly visible manifestation of the extreme distress in which so many millions of Americans live.”

As the movie explains, Williams was born in Chicago. His mother, whom he describes as a “comedy maven,” was a former model originally from Mississippi, and his father a senior executive for Ford Motor Company, responsible for the Midwest region. Both he and his father were fans of iconic comedian Jonathan Winters, whose rapid transformations into multiple characters Williams would come to mimic.

In 1973, he began studying acting at the Juilliard School in New York City, where he and Christopher Reeve were the two students accepted into the Advanced Program by famed producer-director John Houseman. (In one of the movie’s many video clips, Williams is shown flying his baby son around the room during the latter’s christening in homage to the infant’s godfather, Reeve, best known for his role as Superman.)

Williams left Juilliard in 1976. Two years later, he appeared in an episode of Happy Days as “Mork from Ork” and the instant and immense popularity of the character led to Mork & Mindy, which ran for four seasons.

Williams was at his best outside the framework of situation comedy or formulaic Hollywood filmmaking. In Zenovich’s film, we see him describing his improvisational method as “the instant meshing with the audience. It’s like sex without the guilt.” He further explains that “a character can be a comic actor more than a comedian. I don’t tell jokes. I just use characters as a vehicle for me, but I seldom just talk as myself.” And later in the film: “There’s a real incredible rush, I think, when you find something new and spontaneous. I think your brain rewards that with a little bit of endorphins going.”

In the course of Come Inside My Mind, comics such as Eric Idle (Monty Python) and Billy Crystal pay moving tributes. Comic and talk show host David Letterman observes: “In my head, my first sight of him was that he could fly because of the—the energy. It was like observing an experiment. Something special…We knew that whatever it was Robin was doing, we weren’t gonna get close to that.”

One of his writers, Bennett Tramer, explains that “being a writer for Robin’s standup is like being a pinch hitter for Barry Bonds. You’re not necessarily needed, except for special circumstances. But it’s interesting to see how he would build a bit. He had a lightning-fast mind, but it wasn’t like everything he did came to him that night. There was real work and preparation. There was a real thoughtful, analytical process behind it. It probably took him longer to explain it to me than coming together in his mind.”

The feverish approach and the need to maintain it took their toll. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, Williams became a cocaine addict. The tragic death of fellow comic and actor John Belushi from a drug overdose in 1982 impelled Williams to quit, but he spent a lifetime fighting various addictions.

One commentator states that: “He just didn’t operate like normal people. He was very vulnerable that’s for sure. He held onto a lot of things and internalized a lot of things. He felt everything.”

Close friend Crystal notes: “He needed that little extra hug that you can only get from strangers. It’s a very powerful thing for a lot of comedians. That laugh is a—is a drug. That acceptance … that thrill is really hard to replace with anything else.”

Only a few of Williams’ comedy bits can be reproduced in this review, as his physical performance and vocal delivery were, in most cases, at the heart of the performance:

“Yes, God made babies cute, so you don’t eat them. How many people do you know that you would let shit on you, piss on you, keep you up all fucking night? They wake up at five o’clock in the morning, and I don’t know what drug they are on—is there some sort of Fisher-Price cocaine…?”

“A woman would never make a nuclear weapon. They would never make a bomb that kills you. They’d make a bomb that makes you feel bad for a while. See? It’d be a whole other thing. That’s why there should be a woman president. Don’t you see? That’d be a wonderful thing. Be an incredible time for that. There would never be any wars, just, every 28 days, some intense negotiations.”

In 1986, Williams teamed up with Whoopi Goldberg and Crystal to found Comic Relief USA, an annual HBO benefit to raise money for homelessness. And in 1988, he appeared with Steve Martin in an off-Broadway production at New York’s Lincoln Center of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

At the 2003 Critics’ Choice Awards, Williams was nominated, along with Daniel Day-Lewis and Jack Nicholson, for the Best Actor award (for One Hour Photo). Day-Lewis and Nicholson won in a tie. Williams was then invited on the stage to speak: “Thank you. I want to thank Jack Nicholson and Daniel Day-Lewis for giving me this piece of paper. Has their names on it, not mine. And I’m glad to be left out of this incredible group. I want to thank Jack for—he is, to me, the greatest actor, and Daniel Day-Lewis, the greatest actor. And…I’m just a hairy actor. And it’s been a wonderful evening for me to—to walk away with nothing. Coming here with no expectations, leaving here with no expectations…it’s pretty much been a Buddhist evening for me. Thank you.”

Williams’ son Zak lovingly says: “His pathos was seeking to entertain and please. And he felt when he wasn’t doing that, he was not succeeding as a person. And that was always hard to see because in so many senses, he is the most successful person I know and yet he didn’t always feel that.”

Come Inside My Mind treats Robin Williams’ explosive comedy as well as his darker side, but largely ignores the social circumstances in which he matured and worked. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, it was not possible to be in New York City and San Francisco and not absorb something of the epoch’s radicalism. The receding of that radical, free-spirited wave had consequences for artists like Williams, whether he was aware of them or not. He was somehow stranded, brilliantly isolated, attempting single-handedly through his routines to make up for the increasing coldness and selfishness of the times.

The disappointments and retrogression of the 1980s and 1990s, at the height of Williams’ popularity, had to affect his art and emotional condition. There is a slightly hysterical and desperate side to his comedy, fueled at times by drugs and alcohol.

To one extent or another, at considerable cost, he accommodated himself to the ethos of the era—if only to the degree of never commenting on it. (Other than in a few jokes, such as, “I believe that cocaine is God’s way of saying, ‘You’re making too much money.’”) The Wall Street madness, the eruption of militarism, the devastation of industries and cities such as Detroit and Chicago never entered into his comedy.

Williams: “There’s all these drugs—Zoloft, Prozac. I want to have one drug encompassing it all. Call it ‘Fukitol.’ I don’t feel anything. I don’t want to do anything—Fukitol. The closest thing to a coma you’ll ever be.”

At one moment in Come Inside My Mind, Williams reveals: “I did three years of just insane shit… just getting worse and worse and worse. We have these things called ‘blackouts’ as alcoholics. It’s not really blackouts. It’s more like ‘sleepwalking with activities.’ Kind of strange. I believe it’s your conscience going into a witness protection program…As an alcoholic, you will violate your standards quicker than you could lower them. You will do shit that even the devil would go, ‘Dude!’”

Charlie Chaplin captured in indelibly comic images the central dilemmas of his historical moment. Williams’ movies, through no fault of his own, were made during the weakest period in Hollywood’s history up to that point. With a few exceptions and despite a number of marvelous moments, his films were often marred by sentimentality and “family values.” The best known include Popeye(Robert Altman, 1980), The World According to Garp (George Roy Hill, 1982), Moscow on the Hudson (Paul Mazursky, 1984), Good Morning, Vietnam (Barry Levinson, 1987), Dead Poets Society (Peter Weir, 1989), Awakenings (Penny Marshall, 1990), The Fisher King (Terry Gilliam, 1991), Mrs. Doubtfire (Chris Columbus, 1993), The Birdcage (Mike Nichols, 1996) and Good Will Hunting(Gus Van Sant, 1997).

Whatever Williams may have thought he was doing, his numerous appearances before the troops in Iraq and Afghanistan helped lend credibility to those neo-colonial wars. In 2005, Williams told USA Today, “I’m there for (the troops), not for W,” referring to President George W. Bush. Nonetheless, it is not a healthy legacy.

Come Inside My Mind does not attempt to offer an explanation for his suicide. It registers his death as a sad event that greatly affected large numbers of people, including fellow performers.

Williams, as the WSWS wrote, had a “manic delivery and his obsessive desire to please or win over an audience, which seemed to know no bounds or restraints, suggested a fragile mental state. One had to wonder what life was like ‘offstage,’ if there ever were such a thing, for such a personality. How could he possibly be satisfied with everyday life, everyday conversation?” In the Zenovich documentary, comic Lewis Black asserts that Williams “was like the light that never knew how to turn itself off.”

His obvious and highly amused sense of the weirdness and complexity of the world made his comedy initially hum with life. This sustained him for decades, but was finally beaten out of him by a combination of career disappointments, social and political disappointments, and severe physical ailments.

“You’ve got to be crazy. It’s too late to be sane. Too late. You’ve got to go full-tilt bozo ’cause you’re only given a little spark of madness, and if you lose that…you’re nothing. Note, from me to you…Don’t ever lose that, ’cause it keeps you alive.”

At another moment, he was more optimistic: “And that’s what’s exciting, the idea you could explore creativity at any price is like—this is what we’re kind of dealing with as artists, comedians, writers, actors. You’re going to come to the edge, you’re going to look over, and sometimes you’re going to step over the edge, and then you’re going to come back, hopefully.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

Things to ponder

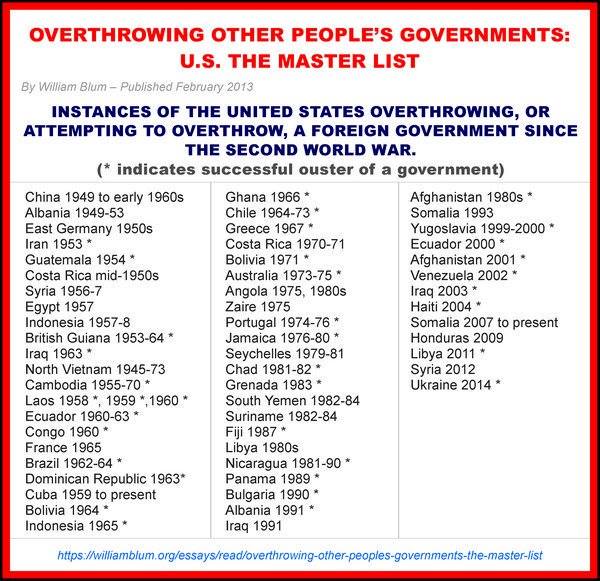

While our media prostitutes, many Hollywood celebs, and politicians and opinion shapers make so much noise about the still to be demonstrated damage done by the Russkies to our nonexistent democracy, this is what the sanctimonious US government has done overseas just since the close of World War 2. And this is what we know about. Many other misdeeds are yet to be revealed or documented.

Parting shot—a word from the editors

The Best Definition of Donald Trump We Have Found

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” — acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump — a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” — acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump — a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report