![]()

The enemy would like the class struggle to stop, go away. It will not, until there is true social justice.

These mutinies remind us all that sailors, soldiers and airmen are first and above all working class people in military uniforms.

By Dave Lamb

A short history of mutinies and rebellions in the British Royal Navy and Marines from the end of World War I, Russian Revolution and up until 1930.

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hilst the mutinies in the German and French Navies in the First World War have been well documented little information is available concerning the British Royal Navy. There was, however, considerable talk of mutiny at Portsmouth, in the summer of 1918. The threat was serious enough for Lionel Yexley, an admiralty agent,[1] to write a report warning the Admiralty of impending trouble. This was only averted by immediate improvements in pay and conditions. Demands for ‘lower deck’ organisation were taken seriously. Agitation for trade union representation was spreading throughout the Navy.

The material conditions of the sailors certainly justified a mutiny. Between 1852 and 1917 there had only been one pay increase, amounting to a penny a day, in 1912. Wartime inflation had reduced the sailors’ nineteen pence a day to a mere pittance. Another twopence a day was granted in 1917, plus a miserable separation allowance of ten shillings and six pence a week, for wives. Following a series of mutinies in 1919 pay increases of over two hundred per cent were granted.

German sailors, soldiers and workers also mutinied in 1918, unleashing the revolution that ended the German monarchy. Image shows mutineers on the Prinzregent Luitpold.

After the Russian Revolution the British Navy was sent into action against the Russians. It proved ineffective, but this ineffectiveness had less to do with the efforts of the Bolsheviks than with the unwillingness of the British seamen to fight. The extent of these mutinies can be measured by reference to the following comment made in the House of Commons by G. Lambert MP, on March 12 1919:

‘…undoubtedly there was, at the end of last year, grave unrest in the Navy… I do not wish to be violent, but I think I am correct in saying that a match would have touched off an explosion.'[2]

Shortly after the armistice with Germany the crew of a light cruiser, at Libau on the Baltic, mutinied. Many other ships were sent home from Archangel and Murmansk after similar experiences. In spite of a propaganda campaign against Russia it was becoming increasingly difficult to obtain reliable crews. Refusals to weigh for Russia were a regular occurrence at Invergordon, Portsmouth, Rosyth, Devonport and Fort Edgar.

Many labour historians have written about the refusal of dockers to load the ‘Jolly George’ with an arms consignment for Poland in May 1920. But we have heard virtually nothing about far greater challenges to authority in the armed forces. For example, early in 1919 a group of dock workers discovered that the destination of a large cruiser being refitted at Rosyth was Russia. Together with some members of the Socialist Labour Party they leafleted the crew, who refused to sail. In fact the crew stayed put for three weeks, although isolated in mid-stream, until their demands were met and they were paid off at Portsmouth.

Meanwhile the crews of the minesweepers operating in the Baltic declared they had had enough. There were incidents aboard the flagship ‘Delhi’, in December, when only 25% of the crew responded to a command to return to Biorko in the Gulf of Finland.

There was a further naval mutiny in Russia, that of the gunboat ‘Cicala’ in the White Sea. Death sentences were imposed on the ‘ringleaders’. The fact that these were later commuted to one year’s imprisonment reflects the continuing strength of the sailors’ movement.[6]

Mutinies in the forces of intervention were not confined to the Navy. There was a large mutiny in a Marine battalion at Murmansk. The 6th Battalion of the Royal Marines, formed in the summer of 1919 at a time of unrest over demobilisation, were originally intended to police Schleswig Holstein. But, at short notice, the Battalion had been diverted to cover the evacuation of Murmansk. They were sent to the Lake Onega region, a further 300 miles south of Kem. In August 1919 two companies refused duty: 90 men were tried and found guilty of mutiny by a court martial. Thirteen men were sentenced to death and others to up to 5 years imprisonment.

None of the death sentences were actually carried out. The 90 mutineers were shipped to Bodmin prison, where they continued their resistance to arbitrary authority. (In this they were acting in the best traditions of the Royal Marines. In December 1918 some Marines had been involved in a mutiny inside Bodmin prison which had resulted in three death sentences, later commuted to five years penal servitude.) Continued resistance paid off. The ninety men arrested after the Murmansk incident had their sentences reduced as follows: the 13 sentenced to death were commuted to five years, but 12 were released after only one year, and the other after two years. Twenty men, originally given 5 years, were released after six months. 51 men sentenced to two years were also released within six months.

In recognition of the fact that their officers had acted contrary to Army instructions in employing young and inexperienced lads at the front, the remainder of those arrested were either released or had their sentences commuted to 6 months. Following the announcement, on December 22, nineteen of these acts of ‘clemency’ the First Lord of the Admiralty told the Commons that ‘bad leadership’ was a factor behind the mutiny. He even hinted at the possibility of disciplinary measures being taken against several officers.

Many other mutinies occurred in North Russia. One took place in the 13th Battalion of the Yorkshire Regiment, which ended with death sentences being passed on two sergeants whilst the other mutineers were cowed by White Russian machine gunners called in by the English officers.

News of these mutinies was suppressed. They highlighted the reluctance of British sailors to fight against Russia when the government was theoretically committed to a policy of peace. Contrary to what the people were being told, and at the very moment when the hysteria surrounding the Armistice was at its height, the Foreign Office and Admiralty were finalising their arrangements for intervention in Russia.

The Navy was not only required for the anti-Bolshevik crusade and to defend Britain’s imperial commitments. It was also needed to quell internal disturbances. Towards the end of the 1914-1918 war seamen were trained in the noble art of ‘blacklegging’ in the event of strikes by railwaymen or power workers. ‘The battleship Vanguard’, says Walter Kendall, ‘was sent to the Mersey to command Liverpool during the Police strike of August 1919’.[7]

Resistance in the Navy continued between 1919 and the time of the large Invergordon mutiny of 1931.[8] In 1930 there were no fewer than six major movements within the Navy against conditions of work and the arbitrary injustice of naval discipline. The ‘Revenge’ (pictured, right), ‘Royal Oak’, Vindictive’, ‘Repulse’, ‘Ramillies’ and ‘Lucia’ were all affected.

Edited by libcom.org from Mutinies by Dave Lamb

Footnotes

1. Lionel Yexley, euphemistically referred to as a ‘naval correspondent’ (see Walter Kendall, The Revolutionary Movement in Britain 1900-1921, London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1969, p. 191) was the editor of a lower deck journal called The Fleet. Yexley had amassed a lot of information about underground naval organisations and his statement that such organisations had existed for ten years was confirmed in Brassey’s Naval Annual of 1919. These incidents are also referred to by Geoffrey Bennett in Cowan’s War (London, Collins, 1964), p. 198. See also Kendall, op. cit. , p. 190

2. Hansard, March 12, 1919

3. Bennett, op. cit., p. 198

4. Ibid., p. 199

5. On December 29, 1919, following a series of acts of militancy, a review of the sentences of those convicted of naval mutiny was announced by the First Lord of the Admiralty. Sentences of up to two years were halved. So were one year sentences. The men serving such sentences had their medals restored. Even the two sailors caught trying to sabot the fan engines of the ‘Vindictive’ had their convictions reviewed after two years.

6. Bennett, op. cit. , p.203

7. Kendall, op. cit., pp. 191-2

8. Wintringham, op. cit., p. 328

Attachment—download this piece in PDF 1918-1930 Mutiny and resistance in the Royal Navy.pdf

ADDENDUM

by Patrice Greanville

AND HERE’S PERHAPS THE MOST HEAVILY SUPPRESSED STORY OF MUTINY, IN THE US NAVY:

The SS Columbia Eagle Mutiny

The famous film (and book) The Caine Mutiny begins by reassuring “patriotic” Americans that there has never been a mutiny in the US Navy. While the book and movie preceded this story, the fact is that events during the Vietnam War were to prove that proud assertion wrong.

Here’s an abridged account. The material comes from Wikipedia, which following the authorities’s approach to manipulate this story to defang its impact, refuse to call it a “mutiny”, preferring to call it, officially, the SS Columbia Eagle “incident”.

The SS Columbia Eagle incident refers to a mutiny that occurred aboard the U.S. flagged merchant vessel Columbia Eagle in March 1970 when two crewmembers seized the vessel with the threat of a bomb and forced the master to sail to Cambodia. The ship was under contract with the Military Sea Transportation Service to carry napalm bombs to be used by the U.S. Air Force during the Vietnam War and was originally bound for Sattahip, Thailand. During the mutiny, 24 of the crew were forced into two lifeboats and set adrift in the Gulf of Thailand while the remainder of the crew were forced to take the ship to a bay near Sihanoukville, Cambodia. The two mutineers requested political asylum from the Cambodian government which was initially granted but they were later arrested and jailed. Columbia Eagle was returned to U.S. control in April 1970

Columbia Eagle

The Columbia Eagle was a Victory-type cargo ship constructed by Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation of Portland, Oregon in 1945 for the U.S. Navy and originally christened Pierre Victory. She was designed to carry all types of dry supplies and munitions to both the European and Pacific theaters of World War II. Like most of the ships of the Victory-type, Pierre Victory was decommissioned after the war and either mothballed or sold to commercial shipping companies. In 1968, she was purchased by the Columbia Steamship Company, renamed Columbia Eagle and contracted out to the Military Sea Transportation Service for the purpose of hauling supplies and ammunition to Southeast Asian ports in South Vietnam and Thailand during the Vietnam War.[8] Because Columbia Eagle was a U.S. flagged ship, she was a part of the Merchant Marine and therefore eligible under government contracting rules to haul military supplies to the war zone.[9]

Clyde William McKay, Jr.

Clyde McKay was born on 20 May 1944 near Hemet, California. His father was in the military at the time and often had duty away from the family. While a teenager, he suffered a misdiagnosed bowel obstruction and was seriously ill for a year. Because of this, he lost a year in school and never finished high school and decided to join the merchant marine. McKay received his merchant marine documents on 23 October 1963 and joined the Seafarers International Union shortly thereafter.[10]

Alvin Leonard Glatkowski

Alvin Glatkowski was born on 11 September 1949 at Augusta, Georgia. His father was also in the military at the time of his birth but shortly after Glatkowski was born, his father abandoned the family. His mother married a Navy third-class machinist mate named Ralph Hagan when Glatkowski was three. Hagan was abusive to Glatkowski when he was home, but was often on duty or cruises and Glatkowski learned to be independent at an early age. As a teenager, Glatkowski assumed the role of head of the household when Hagan was at sea and this made Hagan very angry when he returned home. He often took out his frustrations on Glatkowski violently, which led him to leave home at eighteen. Glatkowski went to New York and enrolled in the Seafarers Harry Lundeberg School of Seamanship operated by the Seafarers International Union. Lundeberg School taught the skills needed to get deck, engine and steward jobs on merchant marine ships. On 17 April 1967, Glatkowski received his merchant mariner papers stating he was eligible for entry-level jobs on U.S. flagged ships.[11]

Mutiny

On 14 March 1970, McKay and Glatkowski used guns they had smuggled aboard to seize control of their ship, SS Columbia Eagle, in the first armed mutiny aboard an American ship in 150 years. The ship had been sailing on a Department of Defense supply charter carrying napalm to the U.S. Air Force bases in Thailand for use in the Vietnam War.

The mutineers claimed that there was a live bomb on board the ship, and forced the captain to order 24 of the crewmen to abandon ship in the lifeboats. The ship’s cargo, 3,500 500-pound bombs and 1,225 750-pound bombs, gave this threat credibility.

When the crewmen departed in lifeboats, a SOS was transmitted. Lieutenant Commander Bob Scalf and his VP-1 Crew 6, the famed “Scalf Hunters”, operating their P-3B from Utapao, Thailand, were directed to launch on a search and rescue (SAR) mission to find the SS Columbia Eagle and assist as needed. Upon arrival at the ship and noticing a small crew and the presence of small arms, Crew 6 immediately reported the hijacking and their assessment that the ship was heading for Cambodia. Communications and status reporting was maintained until they were relieved on station. Crew 6 was awarded a well-done from CTF-72 for their actions.

Other P-3 Orion aircrews relieved VP-1 Crew 6 and each other to keep the Columbia Eagle under constant surveillance while events unfolded. Among them was VP-22 Crew 3, piloted by Lieutenant Commander Norman “Chips” Koehler, which launched on short notice from Sangley Point in the Philippines.

The merchant ship Rappahanock picked up the lifeboats and crew members and broadcast the news of the mutiny. The United States Coast Guard cutter Mellon was the first US military vessel on station, pursuing the Columbia Eagle. The amphibious transport dock USS Denver was diverted to relieve Mellon in its pursuit. The destroyer, USS Turner Joy, DD951, was detached from station at I Corps to pursue the Columbia Eagle at flank speed and to intervene. However, the Columbia Eagle reached Cambodian waters before any U.S. naval assets could intercept.[12]

With only 13 crewmen remaining aboard besides themselves, the mutineers sailed into Cambodian waters, where they assumed they would be welcomed as heroes. They anchored within the 12-mile (22.2 km) territorial limit claimed by Cambodia on the afternoon of 15 March.

At 0951 on 16 March, Denver anchored 15.6 miles (28.9 km) from the coast in the Gulf of Siam, remaining outside Cambodian waters. Mellon joined shortly thereafter with Commander, Amphibious Squadron Seven, as the senior officer present. Two CH-53 Sea Stallion helicopters landed on Denver from bases in Vietnam to assist in visual surveillance. Meanwhile, the mutineers had turned the ship over to Prince Norodom Sihanouk‘s government, declared themselves anti-war revolutionaries, and were granted asylum.[12]

On 17 March, the helicopters were detached and Denver, with Commander, Amphibious Squadron Seven, departed for Singapore, passing on-scene command to Mellon.[12] “Turner Joy” remained on station in a cruising pattern within shipping lanes and in sight of the harbor channel.

On 18 March at 0636, Denver reversed her course; Prince Sihanouk had been deposed by a coup led by the pro-U.S. Sirik Matak and Lon Nol. If the Cambodians could be persuaded to release Columbia Eagle, Denver’s flight deck could help the rescued crew members rejoin their ship. The coup was unfortunate for McKay and Glatkowski; they had hoped to find asylum in a pro-Communist country; instead, they became prisoners of the new Cambodian government. At 2359 on 18 March, Denver anchored in the Gulf of Siam 17.0 miles (31.5 km) from the coast of Cambodia.[12]

Sihanouk, now in exile, charged that the CIA had masterminded the mutiny to deliver weapons to Lon Nol. Both the mutineers and U.S. officials denied his charges, but the damage was done; no Communist forces would shelter the mutineers after they were labeled as CIA stooges.

When it became clear that Columbia Eagle’s release was not imminent, Denver was detached to proceed to Da Nang.[12]

On 8 April, Columbia Eagle was permitted to leave Cambodian waters. She rendezvoused with USCGC Chase where a Navy explosive ordnance disposal team inspected the ship while Chase departed to An Thoi to pick up the Columbia Eagle crew and return them to the ship. With the crew and ship reunited, Chase escorted her to U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay arriving 12 April.[13]

Status

McKay and Glatkowski were held by the post-coup Cambodian government for several months after their capture. A United Press newspaper interview from August 1970[14] describes them as living under guard in “a rusting World War II landing ship moored in the Mekong River,” regularly using marijuana supplied by their guards, and making statements supporting the Manson Family and violent overthrow of the United States government.

After months of imprisonment, Glatkowski was extradited to the United States to face trial. He was charged with mutiny, kidnapping, assault and neglect of duty, convicted, and served his sentence. He has admitted to mistakes in the hijacking but remains unapologetic about their goal of interrupting the napalm shipment.

McKay escaped from his captors along with U.S. Army deserter Larry Humphrey[15] and sought out the Khmer Rouge.[16] He was officially declared missing on 4 November 1970 and has never been located by the authorities. However, Richard Linnett and Roberto Loiederman, co-authors of The Eagle Mutiny, wrote an article, entitled “The Last Mutineer”,[17] for the February 2005 issue of Penthouse in which they report that remains brought back from Cambodia were positively identified as Clyde McKay’s at the Central Identification Laboratory – Hawaii (CILHI), the U.S. Navy’s forensic lab in Hawaii. Subsequently, the remains were cremated and the ashes were buried in the family plot in Hemet, California, where McKay had spent his youth.

Bear in mind, again, that the above is on Wikipedia, a platform heavily influenced by the CIA and otehr government agents. The story, phrasing and outcomes noted should be regarded with caution, as redacted.

WIKIPEDIA SOURCE

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

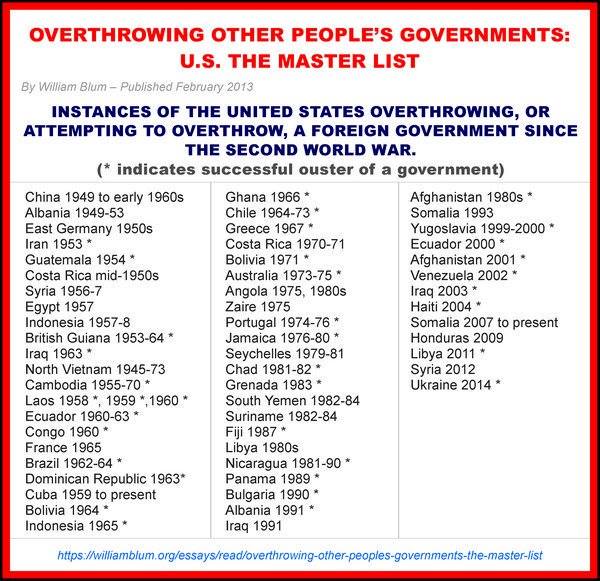

Things to ponder

While our media prostitutes, many Hollywood celebs, and politicians and opinion shapers make so much noise about the still to be demonstrated damage done by the Russkies to our nonexistent democracy, this is what the sanctimonious US government has done overseas just since the close of World War 2. And this is what we know about. Many other misdeeds are yet to be revealed or documented.

Parting shot—a word from the editors

The Best Definition of Donald Trump We Have Found

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” — acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump — a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report

In his zeal to prove to his antagonists in the War Party that he is as bloodthirsty as their champion, Hillary Clinton, and more manly than Barack Obama, Trump seems to have gone “play-crazy” — acting like an unpredictable maniac in order to terrorize the Russians into forcing some kind of dramatic concessions from their Syrian allies, or risk Armageddon.However, the “play-crazy” gambit can only work when the leader is, in real life, a disciplined and intelligent actor, who knows precisely what actual boundaries must not be crossed. That ain’t Donald Trump — a pitifully shallow and ill-disciplined man, emotionally handicapped by obscene privilege and cognitively crippled by white American chauvinism. By pushing Trump into a corner and demanding that he display his most bellicose self, or be ceaselessly mocked as a “puppet” and minion of Russia, a lesser power, the War Party and its media and clandestine services have created a perfect storm of mayhem that may consume us all.— Glen Ford, Editor in Chief, Black Agenda Report