Venezuela Regime Change 'Made in the USA and Canada’ (photo: venezuelanalysis.com)

[First Published by the Greanville Post • 02/12/2019]

Ne touchez pas le Venezuela, le Canada et les États-Unis rentrent chez eux!

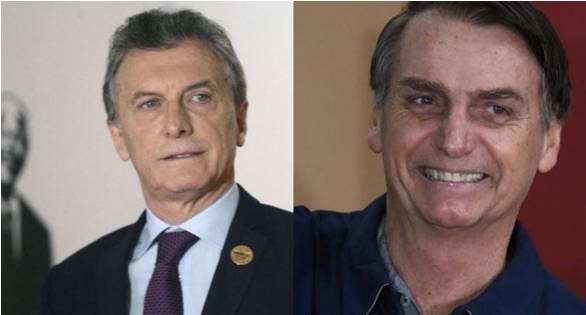

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hat is happening to Venezuela is a coup d'état and it has nothing to do with democracy, human rights, free and fair elections or international law. The US and Canada represent the antithesis of those values; defying the United Nations Charter and international law by interfering in the internal affairs of Venezuela. Their hands are not clean, and their motives are not pure, because their foreign policy objectives everywhere are to promote the interests of their domestic corporations, oligarchs and war profiteers.In 2017 the US and Canada formed a posse of vigilantes that they named the Lima Group. The members of the Lima Group are Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Saint Lucia. Mexico’s newly elected liberal government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) has withdrawn from the Lima Group, saying that Mexico follows the principles of sovereignty, non-intervention, and self-determination in foreign policy. Viva AMLO! The Lima Group makes a mockery out of the United Nations and international law.

The US, which is the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism, handpicked the gang members of the Lima Group. Most are rightwing governments, and politically dominated by business-centric oligarchs, and wealthy families just like those that are trying to take control in Venezuela. Fascism, supported by corporations, elites and imperialists are on the march. There is a new wave of anti-immigrant, xenophobic, evangelical, homophobic, and social conservatives gaining power in Latin America, as elsewhere.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights, Idriss Jazairy specifically condemned the US and Canada for imposing economic sanctions on Venezuela. Jazairy stressed that the economic sanctions are immoral on humanitarian grounds, and they are an illegal attempt to overthrow the internationally recognized sovereign government of Venezuela. On January 31, 2019 the UN released a report that quoted him as saying:

“I am especially concerned to hear reports that these sanctions are aimed at changing the government of Venezuela… Coercion, whether military or economic, must never be used to seek a change in government in a sovereign state. The use of sanctions by outside powers to overthrow an elected government is in violation of all norms of international law…. Economic sanctions are effectively compounding the grave crisis affecting the Venezuelan economy, adding to the damage caused by hyperinflation and the fall in oil prices.”

Former UN Special Rapporteur Alfred de Zayas, who is also an international expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order, said on his website on February 7th the following about the current situation in Venezuela:

“Members of the United Nations are bound by the Charter, articles one and two of which affirm the right of all peoples to determine themselves, the sovereign equality of states, the prohibition of the use of force and of economic or political interference in the internal affairs of sovereign states…… the enormous suffering inflicted on the Venezuelan people by the United States is nothing less than appalling. The economic war against Venezuela, carried out not only by the United States, but also by the Grupo de Lima in clear violation of Chapter 4, Article 19 of the OAS Charter, the financial blockade and the sanctions have demonstrably caused hundreds of deaths directly related to the scarcity of food and medicines resulting from the blockade.”

Zayas also said that what the US, Canada and the mainstream media are doing to Venezuela reminds him of the deliberate disinformation campaign that led to the US, and the “coalitions of the willing” that included Canada anonymously, illegally invading Iraq in 2003, and their destruction of Libya in 2011.

In the case of Libya in 2011, the so-called “no-fly zone” authorized by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973 was for the intended purpose of bringing about a ceasefire. It specifically forbade any “boots on the ground”, which the US is known to have violated.

The US, Canada and other NATO forces illegally exceeded their UN mandate, and used it as a cover to completely destroy Libya and regime change. It later was learned that the supposed Gaddafi genocide, which the no-fly zone was intended to stop was a hoax. The point is that the US and its junior partners can never be trusted to tell the truth when a lie serves their purposes much better.

Whenever the US and its junior imperial partners resort to pleas of democracy and human rights, an ulterior motive should be assumed. For instance, the little the US and Canada care about democracy, human rights and free elections is shown by their long history of supporting non-democratic governments.

Canada has supported every US regime change project, and the overthrow of democratic governments, which did not conform to their mutual foreign policy objectives. Both countries’ foreign policies prefer corrupt business-centric rightwing repressive governments. Democracy and human rights conflict with the interests and profits of their exploitative and extractive corporations.

Both the US and Canada supported the apartheid government of South Africa right up until the very end; they support the apartheid government of Israel, which is the number one violator of human rights in the world; and they both sell arms and support the most repressive government in the world, Saudi Arabia. Human rights have not been an issue.

The US overthrew the democratically elected Salvador Allende of Chile, with Canada’s support. Both countries supported the junta regime of Augusto Pinochet, whom was later arrested for crimes against humanity. Both the US and Canada supported the illegitimate coup governments of Haiti in 2004, and in Honduras in 2009. By some estimates, the US (and Canada) support 73% of the dictators in the world. Human rights have not been an issue.

The US and Canada have been trying to overthrow the democratically elected reformist government of Venezuela, known as the Bolivarian Revolution, since 1999. Hugo Chavez’s elections were all certified by the Carter Foundation, the OAS and other legitimate observers. Chavez was elected in free, fair and democratic elections, but that did not matter to the US and Canada. They wanted to overthrow him anyway. Human rights were not an issue.

Democracy, human rights, the right-to-protect, humanitarian interventions and all the other righteous soundbites are just talking points for the US and Canada. They are only used against governments that get in their way, and never used against corrupt business-friendly governments, no matter how oppressive. Paul Jay, a Canadian, who is the editor-in-chief of The Real News Network says that he personally became aware in 2005 of Canada’s involvement in the conspiracy of regime change in Venezuela:

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he hypocrisy of US concerns over human rights is on full display in a leaked US State Department memo from Brian Hook to then Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. The memo is titled “Balancing Interests and Values”. The memo does not mince words about human rights concerns being only a tactic to use against adversaries:

“America's allies should be supported rather than badgered…. allies should be treated differently -- and better -- than adversaries…. We do not look to bolster America’s adversaries overseas; we look to pressure, compete with, and outmaneuver them…. pressing those regimes [adversaries] on human rights is one way to impose costs, apply counter-pressure, and regain the initiative from them strategically.”

Hook continues his memo by giving Tillerson a history lesson on the art of US hypocrisy from 1940 to 2017.

Egypt's strongman Gen. Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. His rule so far has been characterised by a bloody repression of all opponents, with thousands killed or thrown in prison. US politicians and media naturally look the other way.

In other words, rightwing dictators, military juntas, ethnic cleansing, fraudulent elections, human rights violations, political prisoners, torture and murder should be treated differently, and better, with compliant allies. Even when adversaries are democratically elected, they should be roasted in order to “extract costs”, according to Hook…. but not because the US cares about people.

There is no serious doubt about the legitimacy of the more than a dozen elections in Venezuela between 1998 to 2013. That did not prevent the US and Canada from “extracting costs”, and trying to overthrow Hugo Chavez anyway. Given the examples of the US and Canada overthrowing the democratically elected governments in Chile, Haiti and Honduras, the objections to Maduro are unbelievable.

In the past few years, there have been a half-dozen certified democratic elections in Venezuela. The real motives for opposing Maduro must be something else. It is obvious what that something else is. The real motives behind the US and Canada are Venezuela’s massive wealth in oil, gas, and other natural resources, such as gold, copper and coltan.

There are also tremendous profits to be had by bringing Venezuela into the Washington Consensus. US and Canadian banks profit from IMF and World Bank loans. The corrupt politicians and oligarchs steal the loans, and then it is the poor that have to repay them, through higher prices for life’s necessities, reduced wages and government-imposed austerity. The privatization of state-owned enterprises at corrupt fire-sale prices enrich oligarchs and corporations tremendously.

The Washington Consensus also forces unequal trade agreements and currency devaluation on poor countries. The resulting lower prices are used to extract natural resources, monocrops and sweatshop produced products for export. Small farmers are driven off the land because they cannot compete with dumped US and Canadian tax-payer highly-subsidized agricultural products, such as corn and wheat. Those that suffer are the local farmers, the poor, landless and indigenous people, who go from subsistence, to poverty, to wage slavery.

The chaotic political situation in Venezuela has been purposely made worse by the US and Canada. Since Venezuela is “cursed” with natural resources, especially oil, its economy has historically gone from boom to bust depending on international oil prices.

It was low oil prices, endemic poverty, gross inequality, and neoliberal economic policies that favored the rich in the 1990’s, which swept Chavez into power in the 1998 election. A majority of the Venezuelan people elected Hugo Chavez and his “Bolivarian Revolution” of rewriting the constitution, increasing participatory democracy, frequent elections, and implementing social programs for the poor. The Carter Center (as well as the OAS) certified the election, and praised Venezuela’s modern voting systems as one of the best in the world:

“Venezuelans voted peacefully, but definitively for change. With more than 96 percent voting for the two candidates who promised to overhaul the system, Venezuelans carried out a peaceful revolution through the ballot box”, said Jimmy Carter’s Foundation upon Chavez’s victory.

The US opposed Chavez regardless of fair and democratic elections. A surprisingly honest 2005 article in the Professional Journal of the US Army explained why the US opposed Chavez and the Bolivarian Revolution for economic and geopolitical reasons:

“Since he was elected president in 1998, Chávez has transformed Venezuelan Government and society in what he has termed a Bolivarian revolution. Based on Chávez’s interpretation of the thinking of Venezuelan founding fathers Simón Bolívar and Simón Rodríguez, this revolution brings together a set of ideas that justifies a populist and sometimes authoritarian approach to government, the integration of the military into domestic politics, and a focus on using the state’s resources to serve the poor—the president’s main constituency.”

“Although the Bolivarian revolution is mostly oriented toward domestic politics, it also has an important foreign policy component. Bolivarian foreign policy seeks to defend the revolution in Venezuela; promote a sovereign, autonomous leadership role for Venezuela in Latin America; oppose globalization and neoliberal economic policies; and work toward the emergence of a multipolar world in which U.S. hegemony is checked. The revolution also opposes the war in Iraq and is skeptical of the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT). The United States has worked fruitfully in the past with Venezuela when the country pursued an independent foreign policy, but the last three policies run directly contrary to U.S. foreign policy preferences and inevitably have generated friction between the two countries.” [Emphasis added.] [See Appendix]

Whether it is Chavez or Maduro, the US, Canada and the oligarchs in Venezuela have been trying to kill the Bolivarian Revolution from when it was an infant in the cradle.

The opposition with the support of imperialists have been trying to get rid of the Bolivarian Revolution with every means imaginable. They have tried a US supported military coup against Hugo Chavez in 2002. It failed. They tried strikes by the management of the Venezuelan oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela. It failed. They tried a recall election in 2004. It failed. Obama tried economic sanctions in 2015. It failed. The US and Canada tried an economic blockade in 2017. It has failed, as of this article. They tried to assassinate Maduro with a drone. It failed.

In 2018 the opposition boycotted the election. Maduro won by a landslide. He had invited the United Nations to be election observers, but the opposition kept the UN away. Other international observers certified the election. Now the opposition complains about the integrity of the election observers. The opposition is making a circus out of elections. The objections by the oligarchs, the US and Canada that the 2018 elections in Venezuela where fraudulent is itself a fraud. Their objectives are to knowingly “extract costs” that Venezuela can ill afford.

The US chose Canada to be the mouthpiece for the Lima Group, but the coup is being directed by imperial powers in Washington. Canadian politeness is not working, and its imperialism is out of the closet where it has been hiding. As Canadian historian Yves Engler puts it, the US carries the big stick in Latin America, and Canada comes along afterwards with the billy club. Engler is referring to Canadian peacekeeping missions, which he exposes as actually policing and counter insurgency missions. Yves Engler has written dozens of books and articles on Canadian imperialism.

Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau may be fooling some of the people, some of the time. But he is now under attack at home for corruption. His accusers say that he has obstructed justice in the world-wide corruption scandal involving the powerful international Canadian conglomerate SNC-Lavalin. SNC-Lavalin is a mining, energy and engineering company that is typical of the corrupt face of Canadian imperialism .

Trudeau’s conspiracy with Trump to overthrow the internationally recognized government of Venezuela has unmasked Canada as a second-rate imperial power. Upon closer look, Canada has been protecting its oil and mining companies that have been raping Latin American countries, destroying their environment and poisoning their people for decades. Canadian imperialism has to obey its “deep state” too, as Canadian journalist Bruce Livesey puts it:

“Those who believe the oil industry has become a deep state point to how the political elites, whether Liberal, Conservative or NDP — from Justin Trudeau to Stephen Harper to Rachel Notley — go to bat for the industry….”.

Mining companies as well as oil and gas are a big part of Canada’s “deep state”. They control approximately 50 to 70% of the mines in Latin America, and they are not held accountable in Canadian courts for their destruction to the environment and harm to human beings in foreign countries. They dispossess the indigenous people and poor of their land. They hire goons to threaten, attack and murder those that try to form labor unions, or demonstrate about land confiscation and human rights abuses. Honduras is just one example of what happens when a democratically elected leader is overthrow by a US and Canadian-backed coup; Canadian mining companies move in. It is all exposed in the book “Ottawa and Empire: Canada and the Military Coup in Honduras”, by Tyler Shipley.

All extractive industries wound the planet. That happens with relatively more impunity abroad, but capitalism inflicts severe harm at home, too. [Canadian Mining Companies in Latin America. Photo Council on Hemispheric Affairs.]

“….the NorthWest Mounted Police were created and the Texas Rangers renewed and reorganized in the early 1870s specifically to address the pressing ‘native question’ confronting Texas and western Canada, among the few places where bison still roamed after 1870….. both Austin and Ottawa called on their rural police to manage indigenous populations facing societal collapse….by controlling or denying the Natives access to the bison.”

In other words, both the US and Canada collaborated in killing the buffalo to extinction. It was the coup de grâce for the starving “native question”. [This reminds us that the "settler" capitalist states have been morally despicable practically from inception, all propaganda to the contrary.—Ed ]

Mining is one of Canada’s biggest and most powerful and politically influential industries. Canada has approximately 60% of all mining companies in the world. Canadian companies such as Ascendant Copper, Barrick Gold, Kinder Morgan, and TriMetals Mining have operations in Canada, Latin America and elsewhere. They are continuing the ethnic cleansing of the “native question” in Latin America, and at home. (See map and statistics of Canadian Mining in Latin America.)

Canadian mining and natural resource companies are heavy handed when it comes to First Nations at home. TransCanada Corporation recently was in the news because of its pipeline route, which they are trying to put through First Nation’s land in the Wet'suwet'en territory, in northern British Columbia. On a court order, a militarized unit of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police broke up a road blockade, which the tribal leaders had put up to keep the pipeline company out of their nation. The Mounties whom lacked jurisdiction arrested 14 tribal leaders on their sovereign land.

During the reign of the British Empire, Canada helped the British put down slave rebellions in the Caribbean. Canada was involved in the slave trade, and slavery was legal in Canada until 1834. The products of slavery, such as cotton and sugar were used for trade and to industrialize Canada. When the British conquered New France, the 1760 declaration of surrender signed in Montreal specifically said:

“The Negroes and panis [aborigines] of both sexes shall remain, in their quality of slaves, in the possession of the French and Canadians to whom they belong; they shall be at liberty to keep them in their service in the colony, or to sell them; and they may also continue to bring them up in the Roman Religion.”

In the 19th century Canadian banking and insurance companies, along with those of the British, monopolized finance in British controlled parts of Latin America. Canada is still financially powerful in the English-speaking Caribbean. For example, the Bank of Nova Scotia, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, and the Royal Bank of Canada, as well as Sun Life Financial are dominate in the Bahamas, Belize, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Jamaica, Turks and Caicos, and Trinidad. After the decline of the British Empire, Canada assumed its natural role as a second-rate imperial power and junior partner for US imperialism.

In the Lima Group, Canada is the US’s junior partner. The US has the leading role from behind the curtain. To prove it, right on cue at the January 4th meeting of the Lima Group, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo pulled the curtain back in a video presentation to the group. Pompeo showed the members who they would have to answer to if they did not vote according to Washington’s wishes. The Lima group obeyed, and voted to politically isolate and economically blockade Venezuela, contrary to international law. Leaving nothing to chance, Pompeo again addressed the group from behind the video curtain at their February 4th meeting in Ottawa.

As Christopher Black wrote in New Eastern Outlook:

“The United States is the principal actor in all this but it has beside it among other flunkey nations, perhaps the worst of them all, Canada, which has been an enthusiastic partner in crime of the United States since the end of the Second World War. We cannot forget its role in the aggression against North Korea, the Soviet Union, China, its secret role in the American aggression against Vietnam, against Iraq, Rwanda, Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Syria, Ukraine, Haiti, Iran, and the past several years Venezuela.”

Black left out many other imperial crimes of the partners in Panama, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Somalia, Sudan, the Congo, Palestine, Libya, Yemen, etc. The US and Canada are “always there for each other” and stand “shoulder to shoulder” in war and imperialism, in Justin Trudeau’s own words. Even against Cuba!

As reported by a leading Canadian paper, Canadian diplomats once spied on Cuba on behalf of the Americans. Photo: Retired diplomat John Graham, one who did precisely that. (Globe & Mail)

The current Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs Chrystia Freeland recently referred to Venezuela as being in “Canada’s backyard”. As the SNC-Lavalin case illustrates, the Canadian “backyard” of imperialism also extends to Africa, Asia, the Middle East and former Soviet Union republics, such as Ukraine.

This is not the 19th century. Central America, South America and the Caribbean Islands are not anybody’s back yard. It is insulting, degrading and shows a colonial mentality for the US and Canada to even think about having a backyard.

Hands Off Venezuela, Canucks and Yankees Go Home!

APPENDIX

Defining Venezuela’s “Bolivarian Revolution” Harold A. Trinkunas, Ph.D.

[bg_collapse view="button-orange" color="#4a4949" expand_text="Click here to read US Army document about Venezuelan Revolution" collapse_text="Show Less" ]Defining Venezuela’s “Bolivarian Revolution”

Harold A. Trinkunas, Ph.D.

Venezuelan officers seated with a U.S. major look over an operations order during a U.S. Southern Command exercise in 2001. Venezuela has since severed all other OPEC members whatever military-to-military links with the United States.(US Army)

FINDING A MOMENT in the history of U.S.Venezuelan relations when tensions between the two countries have been worse than at the present time is difficult. Some in the U.S. Government perceive President Hugo Chávez Frias as uncooperative regarding U.S. regional policies on counternarcotics, free trade, and support for democracy. Venezuela’s alliance with Fidel Castro’s Cuba, its opposition to Plan Colombia, and its perceived sympathy for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and other radical organizations are further irritants to the relationship. On the other side. Venezuelan leaders in the Chávez administration believe the United States is fundamentally opposed to the success of the Bolivarian revolution and that U.S. hegemony in the current world order must be checked.

Although officials in both countries occasionally express hope that relations will improve, this is unlikely to happen given the perceptions each country’s foreign policymakers hold of each other.1

Since he was elected president in 1998, Chávez has transformed Venezuelan Government and society in what he has termed a Bolivarian revolution. Based on Chávez’s interpretation of the thinking of Venezuelan founding fathers Simón Bolívar and Simón Rodríguez, this revolution brings together a set of ideas that justifies a populist and sometimes authoritarian approach to government, the integration of the military into domestic politics, and a focus on using the state’s resources to serve the poor—the president’s main constituency.

The Bolivarian revolution has produced a new constitution, a new legislature, a new supreme court and electoral authorities, and purges of Venezuela’s armed forces and state-owned oil industries. These policies consolidated Chavez’s domestic authority but generated a great deal of opposition in Venezuela, including a failed coup attempt in 2002. Even so, after his victory in a presidential recall referendum during the summer of 2004, Chávez seems likely to consolidate his grip on power and even win reelection in 2006.

Although the Bolivarian revolution is mostly oriented toward domestic politics, it also has an important foreign policy component. Bolivarian foreign policy seeks to defend the revolution in Venezuela; promote a sovereign, autonomous leadership role for Venezuela in Latin America; oppose globalization and neoliberal economic policies; and work toward the emergence of a multipolar world in which U.S. hegemony is checked.2 The revolution also opposes the war in Iraq and is skeptical of the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT). The United States has worked

fifllih ihVlhh diddfilibhlhliidil

fruitfully in the past with Venezuela when the country pursued an independent foreign policy, but the last three policies run directly contrary to U.S. foreign policy preferences and inevitably have generated friction between the two countries.3

Still, the geopolitics of oil make it difficult for the United States and Venezuela to escape their traditional economic and political partnership. The United States is Venezuela’s most important consumer of its main export—oil. As a market, the United States possesses key advantages for Venezuela, such as geographic proximity, low transportation costs, and an ever increasing demand for energy. Access to large Venezuelan oil deposits across short, secure sea lines of communication is undoubtedly a strategic asset for the United States. Also, the United States and Venezuela have often found common political ground after Venezuela democratized in 1958, particularly as the rest of Latin America moved away from authoritarianism during the 1980s and 1990s.

Nevertheless, friction between the United States and Venezuela on trade policies, human rights, and regional politics is not new. What is different today about Venezuela’s Bolivarian foreign policy is that it seems to be increasingly at odds with the United States precisely in the areas that once brought the two countries together—oil and democracy.

Venezuela is increasingly ambivalent about its role as a key supplier of oil to the United States, reaffirming its belief in the importance of the U.S. market yet threatening to deny access to oil as a strategic lever against U.S. policies. Chávez has reinvigorated OPEC, which seemed moribund during the 1990s, and he has sought to build direct ties to other non-OPEC oil producers, such as Russia, and new markets, such as China.

Ironically, just as U.S. President George W. Bush’s administration has become more vocal about advocating democratization globally, Venezuela and the United States have fallen out of step. Increasingly, Venezuela espouses an alternative vision of participatory democracy that emphasizes mass mobilization and downgrades the role of institutions. Venezuela also views U.S. support for representative democracy in Latin America as thinly disguised meddling.

To what extent does Venezuela’s Bolivarian foreign policy represent a historic break with the past? Does it represent a threat to U.S. interests? In some ways, current friction between the two countries is a replay of earlier disagreements over oil and democracy. What is new about Chávez’s Bolivarian foreign policy is that it has moved beyond Venezuela’s traditional efforts to maintain an independent foreign policy and maximize oil revenue to one of explicitly seeking out allies in a bid to check U.S. power and influence in Latin America. From the perspective of U.S. policymakers, this goal might seem unfeasible for a country with Venezuela’s limited power and resources. Nevertheless, it is the main axis of Bolivarian foreign policy.

Cooperation and Conflict

The strategic importance of Venezuela to the United States only truly emerged after the discovery in 1914 of major oil deposits in Venezuela. In a sense, the United States was present at the creation of the Venezuelan oil industry. American oil companies and the Royal Dutch Shell Corporation created the physical infrastructure for Venezuela to become the largest oil exporter in the Western Hemisphere. They also were key in shaping Venezuelan oil legislation and the role this natural resource would play in politics. The strategic importance of Venezuelan oil to the United States was confirmed during World War II and reconfirmed time and again during each political or military crisis of the Cold War and beyond.

Despite or perhaps because of these close ties, friction arose between Venezuela and the United States over the U.S. preference for private ownership of the oil industry in Venezuela, led by international corporations, and Venezuela’s preference for policies that maximized national control over this strategic asset. Beginning in the 1940s, Venezuelan democratic governments sought greater access to a share of the oil profit, initially through higher royalties and taxes but, eventually, by state control of the industry itself. Venezuela also promoted its views regarding the importance of national control of oil production in developing countries through its leading role in the creation of OPEC.4

To the credit of both governments, disagreements over oil policy were always resolved peacefully. Venezuela developed a reputation as a reliable supplier of oil to U.S. markets, particularly in moments of international crisis. One historic missed opportunity, at least from the Venezuelan perspective, was that the United States never appeared to be interested in institutionalizing a special relationship with Venezuela over oil, which they blamed on opposition by American oil companies.5

Oil wealth generated during the 1970s allowed Venezuela to pursue a more assertive foreign policy that often irritated the United States. Venezuela’s leading role in OPEC gave it a new prominence during the oil crises of the period. Venezuelan President Carlos Andrés Pérez also promoted a Venezuelan leadership role in the nonaligned movement, which was often critical of U.S. policies.

In 1974, Venezuela reestablished diplomatic relations with Cuba.6 Venezuelan support for the overthrow of dictator Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua in 1979 showcased a willingness to actively subvert governments once considered U.S. allies. Venezuela also sought to contain and change U.S. Central American policies during the 1980s through its leadership role in the Contadora group, promoting confidence building and regional peace negotiations as alternatives to a more confrontational United States stance with Nicaragua and Cuba.7

Certainly Venezuelan influence in the region during the Cold War, especially when backed by abundant oil money, occasionally frustrated U.S. designs. But these actions did not preclude frequent cooperation between the two countries. After the 1958 transition to democracy, Venezuela’s political leaders were firmly convinced of the importance of supporting like-minded governments in the region and opposed the Cuban revolution model on both ideological and pragmatic grounds. U.S. Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson cooperated with the Venezuelans in defeating a Cuban-backed insurgency in Venezuela during the 1960s. United States and Venezuelan militaries developed strong mutual security

and defense links through this experience.

Venezuela’s first leader of the democratic period, Rómulo Betancourt, promulgated a doctrine of nonrecognition of both leftwing and rightwing dictatorships in the Americas. With respect to rightwing dictatorships, this was a step too far for the United States, which often saw rightwing authoritarian regimes as strategic partners in the Cold War.8 Venezuela and the United States found common ground in El Salvador during the 1980s when both provided political support to President José Duarte’s Christian Democratic Government. Venezuela also provided funding and security assistance to assure the survival of the elected government of Violeta Chamorro in Nicaragua after the Sandinista Government ended in 1990. More important, the United States cooperated extensively with Venezuelan political leaders after the 1992 coup attempts to ensure the continuity of representative government.9

Until 1998, leaders in both the United States and Venezuela understood they had important common economic interests that required sustaining a generally positive bilateral relationship. In addition, both countries were democracies that valued freedom and individual liberty, placing them on the same side of the Cold War divide. During this period, Venezuela essentially sought to maintain an autonomous and sovereign foreign policy, promote like-minded democratic governments in the region, and moderate U.S. foreign policy in Latin America. However, it was also careful not to place itself on a collision course with any core U.S. foreign policy interests.

Bolivarian Foreign Policy

The current distance in U.S-Venezuelan relations is greater than any gulf between the two countries during the 20th century. Even on a superficial level, the tone of current government exchanges is often unfriendly, personalized, and frequently characterized by the use of derogatory language.10 This cannot be attributed entirely to U.S. policy toward Venezuela or Latin America, which differs only at the margins from the parameters established by U.S. administrations during the 1990s.

At its core, U.S. policy toward the region has pushed for free elections, open markets, and free trade. The steady trend toward the election of center-left governments in Latin America during the 2000s has produced little reaction from the Bush Administration other than a commitment to develop friendly working relations while mostly adhering to its basic policies on democracy, markets, and trade.11 Even the greater willingness of the Bush administration to employ military force in support of foreign policy and GWOT has not translated into much of a difference for Latin America. The growing U.S. involvement in Colombia is only the continuation of a trend established long before the 2000 elections in the United States. In fact, the great reduction in the use of U.S. military force in the region since the end of the Cold War is notable when recalling previous U.S. efforts during the 1980s in Grenada, Central America, and Panama.12

The changing pattern of Venezuela’s foreign relations since Chávez’s election, particularly its growing closeness to traditional U.S. adversaries such as Cuba and Iran and such potential challengers as Russia and China, disturbs many in the U.S. foreign policy establishment. At the same time, the Chávez administration is completely convinced the United States is hostile to the success of its revolution, pointing to the April 2002 coup attempt as evidence, correct or not, of U.S. designs on its survival. This begs the question: What are the aims of Venezuela’s Bolivarian foreign policy, and are they the source of the growing political distance between the two countries?

Chávez’s first foreign policy objective was revitalizing OPEC, and he has succeeded completely, although he did benefit from burgeoning demand for energy in China, India, and the West. Such an objective represents a return to Venezuela’s 1970s policy of strong support for OPEC. Chávez has reached out to all all other OPEC members whatever their politics, even those on Washington’s short list of least favorite regimes, such as Libya, Iran, and Iraq (before the overthrow of the Hussein dictatorship).13

Chavez has also invested a great deal of time in building relations with Russia and China, the former because of its important oil production capacity, the latter because it is perceived as a major potential consumer of Venezuelan exports. Beyond oil, these two countries are key partners in Venezuela’s Bolivarian foreign policy because they represent alternative sources of technology and military equipment, and their decisions to cooperate with Chávez are unlikely to be influenced by U.S. objections. The logical objective of this policy is to reduce Venezuelan political, economic, and military dependence on the United States. We should remember that Venezuela will find it difficult in the short term to escape its connection to the U.S. oil market because the refineries most capable of processing the particular variety of heavy crude oil increasingly produced in Venezuela are almost all located in the United States.14

In Latin America, Venezuela has sought to achieve a position of leadership and to rally support for regional policies and institutions that exclude the United States. One particular area of friction has been the U.S.-sponsored Free Trade Area of the Americas, to which Chávez has proposed an alternative—the Bolivarian Alternative for Latin America and the Caribbean.15 He also called for an alliance of state oil companies in Latin America, called Petrosur, to foster stronger regional integration in the energy sector. At a hemispheric defense ministerial meeting in 2000, the Chávez administration unsuccessfully proposed integrating Latin American militaries and creating a regional defense alliance without U.S. participation.16 These proposals fit the Bolivarian theme of regional integration and suspicion of the United States.

The Chávez administration has also dissented from the regional political trend toward institutionalizing international policies that defend representative democracy in the region, such as the Organization of American States (OAS) Democratic Charter. Instead, it has showcased its own “participatory democracy” as a superior alternative. The election of Chilean José Miguel Insulza as secretary-general of the OAS with Venezuelan backing is a limited victory on this issue for Chávez.17 Chile has been one of the regional countries most supportive of representative democracy and resistant to Venezuela’s Bolivarian foreign policy, particularly after Chávez’s comments supporting Bolivian access to the Pacific

Ocean at Chile’s expense. However, the OAS may lower the profile of its democracy-promotion activities in the future.

In relation to security measures, Venezuela has suspended all military-to-military links with the United States and has sought alternative sources of military expertise and equipment from Brazil, China, and Russia. Given the central role the military plays in supporting the Chávez administration in Venezuela, the United States takes the loss of these military-to-military contacts seriously. Clearly, Venezuela wants to reduce its dependence on the United States in security and foreign policy and develop an alternative network of allies.18

Chávez is now focusing on communicating his message more effectively internationally. As part of an effort to increase its regional political and communications reach, the Venezuelan Government is developing a regional alternative—Telesur—to U.S.-owned media outlets such as CNN. Telesur is also seen as an important mechanism to circumvent the role of privately owned Venezuelan media companies, which are perceived as actively hostile to the revolution.19

The Venezuelan Government has also provided support to sympathizers across the Americas, in the United States, and throughout the developed world, often sponsoring local Círculos Bolivarianos (Bolivarian circles) to bring together its supporters overseas.20 This has provoked friction with a number of neighboring states, which suspect that the Chávez administration has aided political groups that are either semi-loyal (Bolivia) or disloyal (Colombia) to local democratic regimes. In particular, they worry that the boom in Venezuelan oil revenues might translate into substantial material support for forces opposed to the current democratic order in the politically volatile Andean Ridge.

Since Chávez came to office, U.S. policymakers have expressed concern about Venezuela’s relations with Colombia and Cuba. Venezuela has always had a tense relationship with Colombia because of border disputes and spillover effects of its neighbor’s multiple violent insurgencies. Tensions have worsened since Chávez became more vocal in his opposition to Plan Colombia.

Colombian accusations of Venezuelan material and moral support for the FARC have found a sympathetic ear among U.S. policymakers.21 One of the most salient indications of how much relations between the two countries have worsened is the case of the kidnapping of FARC leader Rodrigo Granda on Venezuelan territory in 2005. The Colombian Government paid a reward, allegedly to members of the Venezuela security forces, for the delivery of Granda to its territory. This led to weeks of tensions between the two countries and a border trade embargo by Venezuela against Colombia. Mediation efforts by Brazil and other regional powers resolved the standoff, but not before revealing the lack of sympathy in the region for Colombia and its ally, the United States.22

Venezuela also entered a de facto alliance with Cuba. Cuban leader Fidel Castro is an important political ally for Chávez, and Cuba is a source of technical expertise to support the Bolivarian revolution. The influx of Cuban doctors, educators, sports trainers, and security experts into Venezuela helps Chávez’s administration meet the demands of its key constituencies. In particular, Cubans provide politically reliable personnel to staff new government poverty alleviation programs. For example, Barrio Adentro places Cuban medical personnel in many poor neighborhoods. In return, Cuba receives nearly 60,000 barrels of oil a day, either on favorable payment terms or as a form of trade in kind.23 Given the longstanding hostility between Washington and Havana, it is not surprising that the new Caracas-Havana alliance has generated suspicions in the U.S. foreign policy establishment.

The Bottom Line

Venezuelan and U.S. national interests have never been identical. We should expect disagreement even in a relationship historically characterized by the mutual interdependence generated by oil, but when it comes to Chávez’s Bolivarian foreign policy, politics trumps economics. Chávez seems likely to win reelection in 2006, and it appears he will be around for a considerable period of time, which puts the United States in a bind when it comes to dealing with the Bolivarian revolution.

A policy of engagement, which is what the U.S. Government attempted in the first 2 years of Chávez’s administration, appears unlikely to generate a solid working relationship given Venezuela’s Bolivarian foreign policy objectives. The United States’ efforts to work with Venezuela since 1998, even on such noncontroversial issues as disaster relief, have met with rejection. However, there appears to be little sympathy, in Latin America and internationally, for a policy of confrontation with the Venezuelan Government. International reaction to the 2002 coup in Venezuela and the reaction in Latin America to the Venezuela-Colombia crisis over Granda’s kidnapping confirm this. If Washington pursues such a diplomatic policy toward Chávez, he has already demonstrated that the likely outcome would be the isolation of Washington and its regional allies—not of Venezuela.

Washington’s dilemma does not mean Venezuela’s Bolivarian foreign policy is likely to succeed to any great extent. Venezuela has achieved its minimum foreign policy objective—the defense of the revolution. However, its leadership role in Latin America is still limited at best, and its efforts to construct alternative regional institutions have failed. Brazil still remains South America’s leading power with long-established ambitions of its own.

Venezuela has succeeded in revitalizing OPEC, although worldwide demand for energy in the 2000s was likely to provide this opportunity even in the absence of Chávez’s leadership. Venezuela’s alliance with Cuba serves mostly to strengthen the Chávez administration in domestic rather than international politics. Despite Venezuelan opposition to Plan Colombia, the Colombian state has become stronger and better prepared to deal with violent nonstate actors within its territory, and the FARC has lost ground since Chávez came to power.

Venezuela’s new alliances with Russia and China are unlikely to produce much in the way of military advantage for this country vis à vis its neighbors particularly in light of Colombia’s growing strength Even the development of alternative markets for Venezuelan oil exports seems

neighbors, particularly in light of Colombia s growing strength. Even the development of alternative markets for Venezuelan oil exports seems difficult to justify on anything other than political grounds since the economics of oil so strongly favor a U.S.-Venezuelan trade relationship.

A final question remains. Will Venezuela’s new political model be emulated across the region? This seems unlikely. The Bolivarian revolution, which is not a coherent ideological model that can be replicated in other countries, depends on Chávez’s personality, charisma, and drive. The Bolivarian revolution increasingly depends on distributing large amounts of oil income to serve key constituencies in Venezuela. Other Latin American countries lack such resources, and in the past have not had much success at redistributing wealth. This does not mean, however, that the underlying sources of political volatility in Latin America, such as poverty, extreme income inequality, and poor economic policies, will soon disappear. Much to the consternation of Washington, governments that sympathize with some elements of the new Venezuelan foreign policy will emerge, particularly in the Andean region where democracy seems most vulnerable. MR

NOTES

- Juan Forero, “U.S. Considers Toughening Stance toward Venezuela,” New York Times, 26 April 2005.

- Elsa Cardozo da Silva and Richard S. Hillman, “Venezuela: Petroleum, Democratization and International Affairs,” in Latin American and Caribbean Foreign Policy, eds., Frank O. Mora and Jeanne K. Hey (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2003), 158-60,

- Carlos A. Romero, “The United States and Venezuela: From a Special Relationship to Wary Neighbors,” in The Unraveling of Representative Democracy in Venezuela, eds., Jennifer L. McCoy and David Myers (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 144-46.

- Terry L. Karl, The Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petrostates (Berkeley: The University of California Press, 1997).

- Frank Tugwell, The Politics of Oil in Venezuela (California: Stanford University Press, 1975).

- Cardozo and Hillman, 150-52.

- Michael Barletta and Harold Trinkunas, “Regime Type and Regional Security in Latin America: Toward a ‘Balance of Identity’ Theory,” in Balance of Power: Theory andPractice in the 21st Century, eds., T.V. Paul, James J. Wirtz, and Michel Fortmann (California: Stanford University Press, 2004), 334-59.

- Harold A. Trinkunas, Crafting Civilian Control of the Military in Venezuela: A Comparative Perspective (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming2005)

- Ibid.

- Maria Lilibeth da Corte, “Lagos le echó un balde de agua fría a Rice” [Lagos throws a bucket of cold water on Rice], on-line at http://www.eluniversal.com/2005/04/30/pol_art_30108AA.shtml (http://www.eluniversal.com/2005/04/30/pol_art_30108AA.shtml), accessed 2 June 2005.

- Larry Rohter, “With New Chief, Uruguay Veers Left in Latin Pattern,” New York Times, 1 March 2005.

- Of note is that none of those instances provoked the distance we currently see in U.S.-Venezuelan relations, although in all three cases Venezuela did not support U.S.policy. See Janet Kelly and Carlos A. Romero, The United States and Venezuela: Rethinking a Relationship (New York: Routledge, 2002), 96-108.

- Ibid.

- Joanne Shore and John Hackworth, “Impacts of the Venezuelan Crude Oil Production Loss,” Energy Information Administration, U.S. Department of Energy, Washington, D.C., 2003; Daniel Fisher, “Hugo’s Folly,” Forbes.com., on-line at http://www.forbes.com/business/energy/2005/02/03/cz_df_0203citgo.html (http://www.forbes.com/business/energy/2005/02/03/cz_df_0203citgo.html), accessed 11 July 2005.

- “Chávez: Venezuela no está interesada en tratado de libre comercio con EEUU” [Venezuela is not that interested in free trade with the United States], El Universal (12 July 2004).

- Romero, 143.

- Joel Brinkley and Larry Rohter, “Chilean, Once Opposed by U.S., is Elected Head of O.A.S.,” New York Times, 3 May 2005.

- Juan Forero and Brian Ellsworth, “Arms Buying by Venezuela Worries U.S.,” New York Times, 15 February 2005; “Venezuela Ends Military Ties and Evicts Some U.S.Officers,” New York Times, 25 April 2005; Pedro Pablo Peñaloza, “No aceptamos críticas a reequipamiento de la FAN [Fuerzas Armadas Nacionales]” [We do not acceptcriticism of reequipment of the FAN (National Armed Forces)], El Universal (28 April 2005).

- Pascal Fletcher, “Chávez TV Channel Aims to be Latin American Voice,” Reuters, 12 April 2005.

- Casto Ocando, “Redes chavistas penetran en EEUU” [Chavista networks penetrate United States], El Nuevo Herald, 12 March 2005.

- Trinkunas, 2005.

- “Brasil facilitará dialogo entre Venezuela y Colombia por crisis” [Brazil facilitates talks between Venezuela and Colombia about crisis], El Universal (19 January 2003), on-line at http://buscador.eluniversal.com/2005/01/19/pol_ava_ 19A524769.shtml (http://buscador.eluniversal.com/2005/01/19/pol_ava_%2019A524769.shtml), accessed 2 June 2005; “Chávez: Secuestro de Granda es una nueva arremetida de Washington” [Abduction of Granda is new attack by Washington], El Universal (23 January 2005), on-line at http://buscador.eluniversal. com/2005/01/23/pol_ava_23A525919.shtml (http://buscador.eluniversal.%20com/2005/01/23/pol_ava_23A525919.shtml), accessed 29 April 2005.

- Trinkunas, 2005.Harold A. Trinkunas is an assistant professor in the Department of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School, School of International Graduate Studies, Monterey, California. He received a B.S. from the University of Pennsylvania and an M.A. and a Ph.D. from Stanford University.

David William Pear is a columnist writing on U.S. foreign policy, economic and political issues, human rights and social issues. David is a Senior Contributing Editor of The Greanville Post (TGP) and a prior Senior Editor for OpEdNews (OEN). David has been writing for The Real News Network (TRNN) and other publications for over 10 years. David is a member of Veterans for Peace, Saint Pete (Florida) for Peace, CodePink, and the Palestinian-led non-violent organization International Solidarity Movement. First Published by the Greanville Post. ]

David William Pear is a columnist writing on U.S. foreign policy, economic and political issues, human rights and social issues. David is a Senior Contributing Editor of The Greanville Post (TGP) and a prior Senior Editor for OpEdNews (OEN). David has been writing for The Real News Network (TRNN) and other publications for over 10 years. David is a member of Veterans for Peace, Saint Pete (Florida) for Peace, CodePink, and the Palestinian-led non-violent organization International Solidarity Movement. First Published by the Greanville Post. ]

THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License