Boeing 737 MAX Crash Reveals Severe Problem With Older Boeing 737 NGs

![]() DISPATCHES FROM MOON OF ALABAMA, BY “B”

DISPATCHES FROM MOON OF ALABAMA, BY “B”

By the editor of Moon of Alabama

The 737 MAX case is important for what it says about an amoral business culture in which only profits matters, and lives are not even a secondary consideration.

•The Boeing 737 is the best-selling airliner of all time.

•Through October, Boeing has taken 14,985 orders for the plane.

•Since 2011, the new 737 MAX has won more than 4,700 orders, making it the fastest-selling airplane in Boeing history.

•Since its debut in 1967, the 737 has become a mainstay for airlines around the world in a number of roles, ranging from short-haul flights to transatlantic routes.

•The 737 is also deployed as a freighter, a business jet, and in military applications.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he fleet of Boeing 737 MAX planes will stay out on the ground longer than anticipated. Boeing promised a new software package to correct the severe problems with its Maneuver Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS). The delivery was supposed to be ready in April. A month later it has still not arrived at the Federal Aviation Agency where it will take at least a month to certify it. The FAA will not be the only one to decide when the plane can come back into the flight line. Other countries' agencies will do their own independent review and will likely take their time.

The 737 MAX incident also revealed a problem with older generations of the 737 type of plane that is only now coming into light. Simulator experiments (video) showed that the recovery procedures Boeing provided for the case of a severe mistrim of the plane is not sufficient to bring the plane back under control. The root cause of that inconvenient fact does not lie with the 737 MAX but with its predecessor, the Boeing 737 Next Generation or NG.

This was known in pilot circles for some time but will only now receive wider public attention:

The Boeing 737 Max's return to commercial airline service is reportedly being further delayed by the Federal Aviation Administration.US government officials told The Wall Street Journal's Andy Pasztor that the FAA is evaluating the emergency procedures for not only the Max but also the older generations of the 737 including the [once] hot-selling Boeing 737 NG.

According to the officials, the broadened evaluation will take a look at how pilots of all 737 variant are instructed to respond to emergency situations.

Here is a detailed explanation why the FAA is now looking into the pilot training for older 737 types.

The 737 NG (-600/-700/-800/-900) was the third generation derivative of the 737 and followed the 737 Original (-100/-200) and Classic (−300/-400/-500) series. The first NG flew in 1997. Some 7,000 were build and most of them are still flying.

Two technical modifications that turned out to be a problem during the recent incidents occurred during the redesign of the 737 Classic into the New Generation series.

In the NG series a new Flight Management Computer (FMC) was added to the plane. (The FMC helps the pilots to plan and manage the flight. It includes data about airports and navigation points. It differs from the two Flight Control Computers in that it has no control over physical elements of the plane.)

The FMC on the NG version has two input/output units each with a small screen and a larger keyboard below it. They are next to the knees of the pilot and the copilot They are located on the central pedestal between the pilots right below the vertical instrument panel (see pic below). The lengthy FMCs did not fit on the original central pedestal. The trim wheels on each side, used to manually trim the airplane in its longitudinal axis or pitch, were in the way. Boeing's 'solution' to the problem was to make the manual trim wheels smaller.

737 NG cockpit with FMC panels and with smaller trim wheels (black with a white stripe)

737 Original-200 cockpit with larger trim wheels (black with a white stripe)

The smaller trim wheels require more manual force to trim with the same moment of force or torque than the larger ones did.

Another change from the 737 Classic to the 737 NG was an increase in the size of the rear horizontal flight surface, the stabilizer.

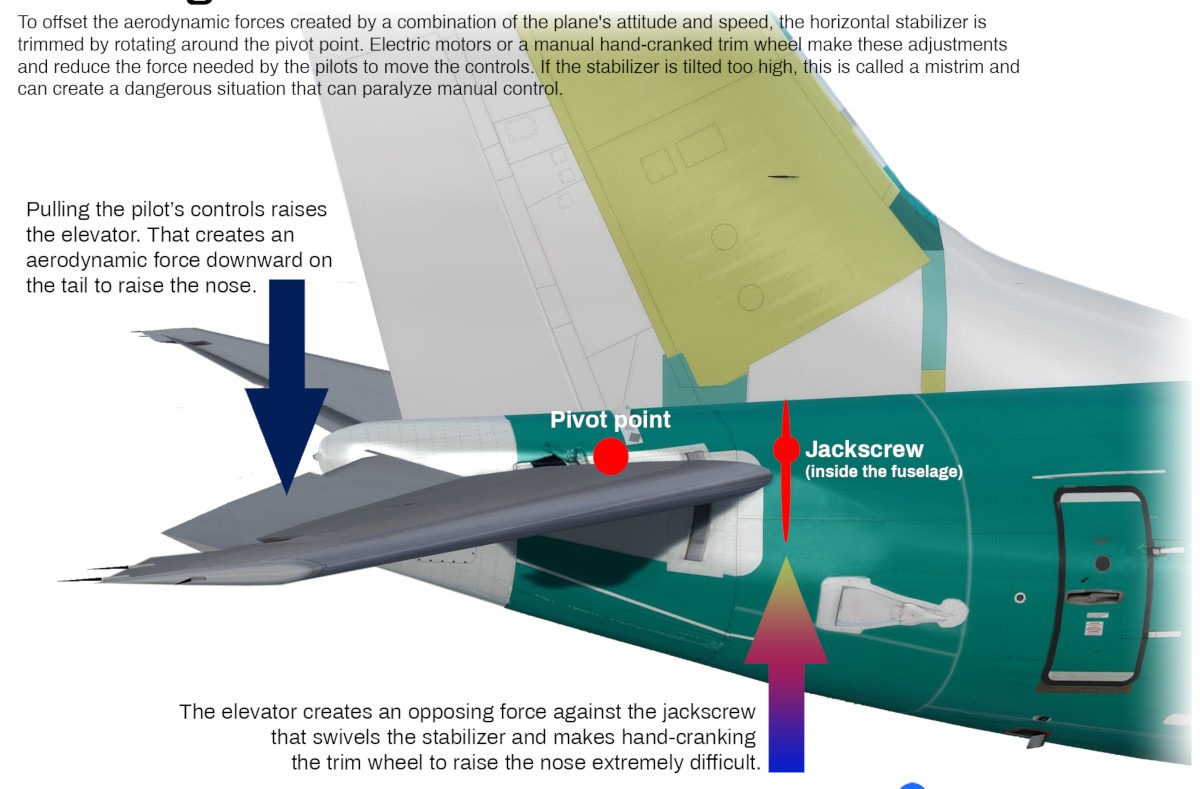

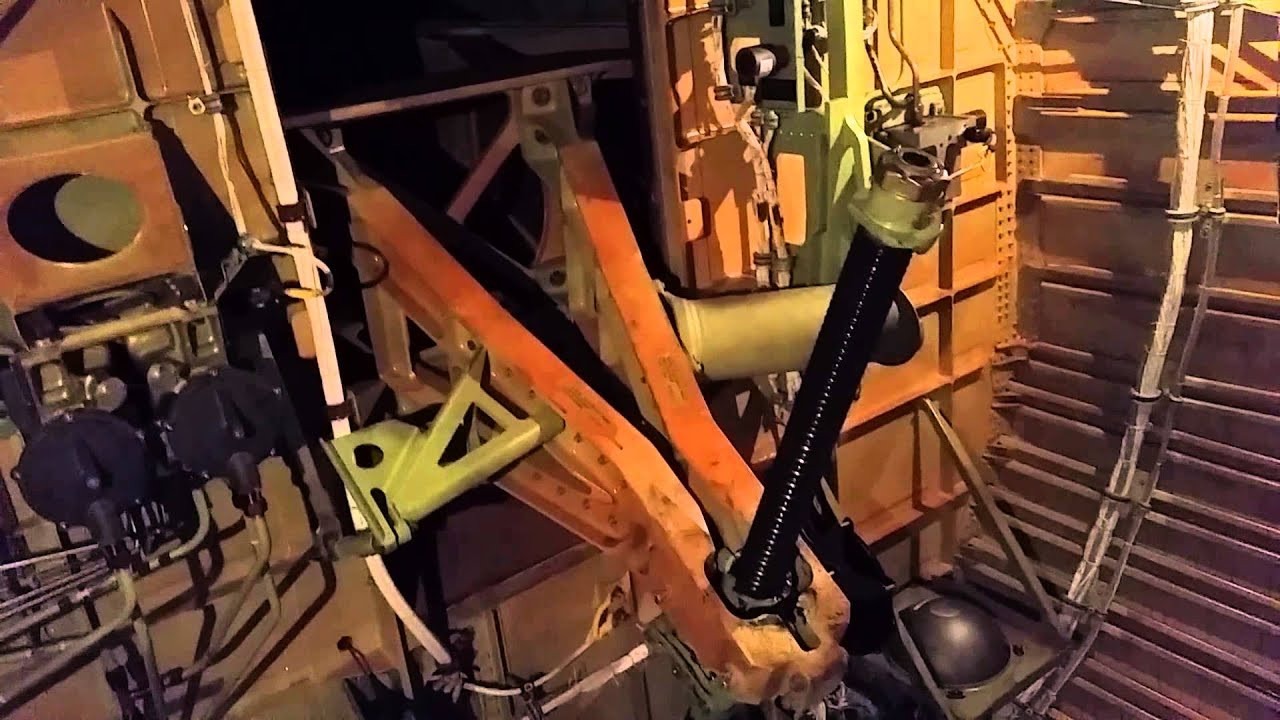

The stabilizer at the rear of the plane can be turned around a central pivot point. The natural nose up or nose down characteristics of an airplane change during a flight depending on the speed at which the airplane flies. The stabilizer can be moved during a flight by a jackscrew (vid) which is turned by either an electric motor, or via cables from the hand-cranked trim wheels in the cockpit. Trimming the airplane keeps it level at all flyable speeds.

At the rear end of the stabilizer is the elevator surface (blue arrow in the pic below). The elevator is moved by the column or yoke the pilot uses to control the plane. During a flight the pilot, or an automated stabilizer trim system (STS), will electrically trim the stabilizer so that no additional force on the column is required for the plane to stay at its flight level.

In case of a mistrim of the stabilizer, the plane puts its nose up or down and the pilot will have to push or pull his column to move the elevator to counter the mistrim of the stabilizer. Depending on the position of the stabilizer and the speed of the airplane this can require very significant force. In some cases it might be impossible.

Graphic via The Air Current and Peter LemmeThe size of the stabilizer increased from 31.40 square meter on the Classic to 32.78 sqm on the NG and MAX. Meanwhile the size of the elevator, the primary control surface the pilot can use to counter a mistrimmed stabilizer, was kept at its original size of 6.55 sqm.

It is therefore more difficult for the pilot of a 737 NG or 737 MAX plane to use the elevator to counter a mistrimmed stabilizer than it was on the earlier 737 Classic series.

In 1961 a mistrimmed stabilizer on a Boeing 707 caused the crash of an airplane. All on board died. The root cause was a malfunction in the electrical switch the pilot normally uses to electrically move the stabilizer. The switch stuck in an ON position and the motor moved the stabilizer to its most extreme position. The plane's nose went up until it aerodynamically stalled. The pilots were unable to recover from the situation.

The type of incident where an electric malfunction drives the stabilizer into an extreme position is since known as a 'runaway stabilizer'.

To get a type rating for Boeing planes the pilots have to learn a special procedure to diagnose and correct a runaway stabilizer situation. The procedure is a so called 'memory item'. The pilots must learn it by heart. The corrective action is to interrupt the electric circle that supplies the motor which drives the jackscrew and moves the stabilizer. The pilots then have to use the hand-cranked trim wheels to turn the jackscrew and to bring the stabilizer back into a normal position.

737 stabilizer jackscrew[The MCAS incidents on the crashed 737 MAX were not of the classic runaway stabilizer type. A runaway stabilizer due to an electric malfunction is expected to move the stabilizer continuously. The computerized MCAS operated intermittently. It moved the stabilizer several times, with pauses in between, until the mistrim became obvious. The pilots would not have diagnosed it as a runaway stabilizer. Only in the end are the effects of both problems similar.]

A third change from older 737s to newer types involved the manuals and the pilot training.

If due to a runaway stabilizer event the front end of the stabilizer moves up, the nose of the airplane will move down and the plane will increase its speed. To counter that the pilot pulls on his column to move the rear end of the elevator up and to bring the plane back towards level flight. As the plane comes back to level the aerodynamic pressure on the mistrimmed stabilizer increases. Attempts to manually trim in that situation puts opposing forces on the jackscrew that holds the stabilizer in its positions. The aerodynamic forces on the stabilizer can become so big that a manual cranking of the trim wheel can no longer move the jackscrew and thereby the stabilizer.

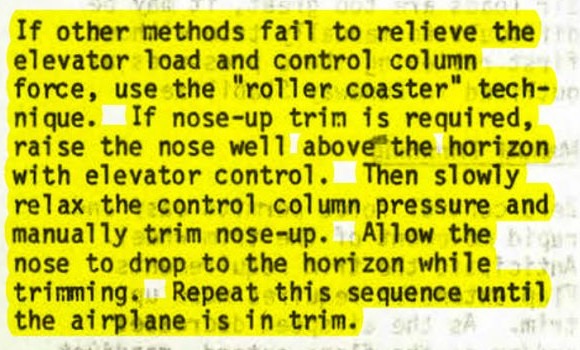

Until the introduction of the newer 737 types Boeing's pilot manuals for the 737 included a procedure that described how to overcome the situation. It was counterintuitive. If the stabilizer put the plane in an extreme nose down position the pilot was advised to first pull the column to decrease the speed. He then had to push the column forward to lower the aerodynamic forces that blocked the jackscrew. Then the manual trim wheel could be turned a bit while the plane continued to dive and again increased its speed. The procedure had to be repeated several times: pull column to decrease speed; push column to decrease the aerodynamic force on the stabilizer and its jackscrew; trim manually; repeat. The technic was known as the rollercoaster maneuver.

Excerpt from an old 737-200 manual - via The Air Current

Excerpt from an old 737-200 manual - via The Air Current

Recently some pilots used a 737 NG flight simulator to test the procedure. They simulated the runaway stabilizer case at a height of 10,000 feet and use the rollercoaster maneuver to recover from the mistrim. When they finally had the stabilizer back into a correct trim position they found themselves at 3,000 feet height. The maneuver would thus help only when the plane is already at a significant height above ground.

Both of the recent 737 MAX crashes happened shortly after the start. The rollercoaster maneuver would not have helped those flights. But should a runaway stabilizer incident happen on a 737 NG at its normal flight level the maneuver would probably be the only chance to recover from the situation.

The crashes of the two 737 MAX revealed a number of problems with the design of the MCAS system. Several additional issues with the plane have since become known. There may be other problems with its 737 MAX that no one yet learned of. The rather casual FAA certification of the type was clearly not justified.

But the problems described above are 737 NG problems. The 380 or so existing 737 MAX are currently grounded. But some 7,000 737 NG fly about every day. The record provides that it is a relatively safe airplane. But a runaway stabilizer is a well known electrical malfunction that could by chance happen on any of those flights.

The changes from the 737 Classic to the 737 NG make it more difficult, if not impossible, for the pilots to recover from such a situation:

- The smaller manual trim wheels on the 737 NG make it more difficult to trim a runaway stabilizer back into a regular position.

- The larger stabilizer surface makes it more difficult to counter a runaway stabilizer by using the elevator which was kept at the same size.

- 737 NG pilots no longer learn the rollercoaster maneuver that is now the only way to recover from a severe mistrim.

Simulator sessions demonstrate (video) that a runaway stabilizer incident on a 737 NG can no longer be overcome by the procedures that current Boeing manuals describe.

It is pure luck that no NG crash has yet been caused by a runaway stabilizer incident. It is quite astonishing that these issues only now become evident. The 737 NG was certified by the FAA in 1997. Why is the FAA only now looking into this?

The second 737 MAX crash revealed all these issues to a larger public. Except for MCAS the trim systems on the NG and MAX are similar. The Ethiopian Airline flight 302 did not experience a runaway stabilizer, but the multiple engagement of MCAS moved the stabilizer to a similar extreme position. The pilots cut the electricity to the stabilizer motor and tried to re-trim the plane manually by turning the trim wheels. The aerodynamic forces on the stabilizer were impossible to overcome. The pilots had not learned of the rollercoaster maneuver. (Not that it would have helped much. They were too low to the ground.) They switched the motor back on to use manual electrical trim to re-trim the aircraft. Then MCAS engaged again and put them into the ground.

All NG and MAX pilots should learn the rollercoaster maneuver, preferable during simulator training. There are probably some 50,000 pilots who are certified to fly a Boeing NG. It will be an enormous and costly effort to put all of them through additional training.

But it will be more costly, for all involved, if a 737 NG crashes and kills all on board due to a runaway stabilizer incident and a lack of pilot training to overcome it. Such an incident would probably keep the whole NG fleet on the ground.

Pilots, airlines and the public should press the FAA to mandate that additional training. The FAA must also explain why it only now found out that the problem exists.

---

Previous Moon of Alabama posts on Boeing 737 issues:

- Boeing, The FAA, And Why Two 737 MAX Planes Crashed - March 12 2019

- Flawed Safety Analysis, Failed Oversight - Why Two 737 MAX Planes Crashed - March 17 2019

- Regulators Knew Of 737 MAX Trim Problems - Certification Demanded Training That Boeing Failed To Deliver - March 29 2019

- Ethiopian Airline Crash - Boeing Advice To 737 MAX Pilots Was Flawed - April 9 2019

Additional sources with more technical details:

- Vestigal Design Issues Cloud 737 MAX Crash Investigation - Jan Ostrower, The Air Current

- Stabilizer Trim - Peter Lemme, Satcom Guru

- Trim Cutout with Severe Out-of-Trim Stabilizer can be difficult to recover - Peter Lemme, Satcom Guru

- Professional Pilots Rumors Forum and News - Various authors in a number of 737 threads, PPRuNe

Posted by b on May 25, 2019 at 21:20 UTC | Permalink

This article is part of an ongoing series of dispatches from Moon of Alabama

"b" is the pseudonym of Moon of Alabama's chief editor and writer.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

[/su_box]