Howard Bryant

Howard Bryant

First iteration July 20, 2018

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hile researching my book “The Heritage,” I was struck by the enormous effect the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks have had on sports — how they look, how they’re packaged and how they’re sold. Before 9/11, giant flags and flyovers were reserved for the Super Bowl. Today, they are commonplace. Even the players wear camouflage jerseys. The military is omnipresent. And it’s by design.

The public accepts this as supporting the troops, but one group of individuals — the veterans themselves — is more skeptical. One voice stood out: William Astore's.

"They bring out a humongous flag," he says. "Military jets fly overhead, sometimes it’s a B-2 stealth bomber, sometimes it’s fighter jets."

Bill Astore is a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel who writes about the increased militarization of sports — and its perils — on Bracing Views, his personal blog, as well as the website Tom Dispatch.

"I think, at first, there’s a sort of thrilling feeling," Astore says. "I’m like all the other fans: a big plane goes overhead — ‘Wow!’ That's kind of awe inspiring. But at the same time, to me, it’s not something that I see should be flying over a sports stadium before a baseball game or a football game. You know, these are weapons of death. They may be required, but they certainly shouldn't be celebrated and applauded."

Astore grew up in Brockton, Massachusetts, the bare-knuckle town of famed boxers Rocky Marciano and Marvelous Marvin Hagler. He’s an avid Red Sox fan, and when he watches sports, he sees the perpetual selling of war, and something very cynical: patriotism for sale, with troops as bait.

The MLB All-Star Game in Washington, D.C., this week was so awash in ceremony, it conjured thoughts of an old joke with a new twist: “I went to a military parade and a baseball game broke out.”

"I think our military has made a conscious decision, and that decision was, as much as possible, to work with strong forces within our society," Astore says. "I think our military made a choice to work with the sporting world — and vice versa. I think that's something that's in response to 9/11."

Before 9/11, an American flag the size of a football field was unheard of.

A C-5 Galaxy flies over Gillette Stadium, Foxboro, Mass., Nov. 11, 2012. Many NFL teams have incorporated extensive patriotic displays in their pregame routines. (USAF photo)

"What I remember from going to games is: I remember the national anthem, a conventional-sized American flag, and that’s all I remember," Astore says. "And I have to say that I thought that was enough.

"You know, after 9/11, there were so many people that I saw who broke out the flags and put them on their cars and had a spontaneous reaction to a feeling that we, as Americans, needed to come together. And that felt good."

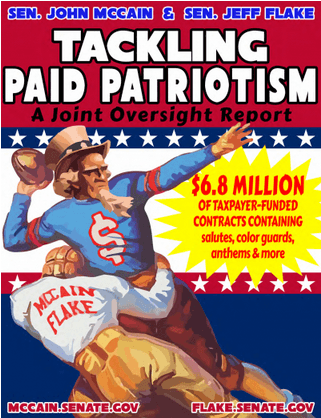

In the years following 9/11, professional sports took a healing gesture and transformed it into a way to make money. In 2015, Republican Sens. John McCain and Jeff Flake released the report “Tackling Paid Patriotism,” which criticized the deceptive, taxpayer-funded contracts between the Pentagon and virtually every pro sports league. In 2012, the New York Army National Guard paid the Buffalo Bills $250,000 to conduct on-field re-enlistment ceremonies. In 2014, the Georgia National Guard paid the Atlanta Falcons $114,000 to sing the national anthem. In 2015, the Air Force paid NASCAR $1.5 million in part for veterans to shake hands with racing legend Richard Petty. Your tax dollars. At work.

"I hate to say it, but I wasn't completely surprised," Astore says. "But I was disgusted by it. Patriotic displays, they mean a lot more to me when they're spontaneous. But to learn that these had been paid for — that corporate teams, teams owned by billionaires, basically, were collecting money from the military. Paid for, obviously, by you and me, by the American taxpayer. Well, it was sad."

American flags are the ultimate Good Housekeeping seal. And thanking veterans for their service disconnects the public from what has been nearly two decades of war. The ballpark ceremony obscures the realities of war and, by focusing on soldiers, inoculates the government from antiwar criticism. Astore tells me it’s a form of emotional manipulation.

"Under the Bush-Cheney administration, we weren’t even able to see the caskets of dead soldiers," Astore says. "The cost of war — that very ugly face of war — was being kept from us.

"And the only time we see it, sometimes, is when they bring out a wounded soldier, for example. And maybe he or she has lost two or three limbs, but they’re brought out into an NFL stadium or an MLB baseball game. And the impression that you get is, 'Everything’s OK, see?' But we don’t see this person struggling to get around at home. And maybe being depressed because they’ve suffered this horrible wound in war."

Nick Francona grew up in baseball. His last name is a dead giveaway. His grandfather, Tito Francona, played 15 years in the big leagues and was teammates with Hank Aaron in the 1960s. His father, Terry, played 10 years in the majors, and, famously, managed the 2004 Red Sox to their first World Series in 86 years.

Nick took a different path.

"I was in my freshman year at Penn," Nick says. "A friend of mine that I played travel baseball with, he had enlisted after high school and was an infantry Marine. And he was in Iraq during my freshman year in college. And it used to keep me up at night. And it would bother me a lot where I would kind of sit there and be, like, 'Man, I’m playing a lot of online poker, going to econ classes, and going out to bars and, like, we have a war going on.' I felt like I was missing out and not contributing or not doing my part."

“I remember the national anthem, a conventional-sized American flag, and that’s all. And I thought that was enough.”

Bill Astore

Nick joined the Marines, becoming a scout sniper platoon commander in Afghanistan.

"I remember my mom, at one point, wanted me to — she was, like, ‘Well, you can pick any of the jobs. Why don’t you be a comptroller or a finance-type of officer?’ " Nick recalls. "I'm like, ‘Mom, no one watches a Marine commercial and is, like, I really want to do the accounting for them.' "

Almost immediately, Nick felt the commercial effects of post-9/11 sports. In May 2010, even before he was deployed overseas, he was being sold as a hero. It felt inauthentic.

"They were having Marine Week in Boston, and it was a pretty big deal," Nick says. "They had wanted me to throw out the first pitch at Fenway during one of the games. It would’ve been a good story of having the manager’s son being a Marine and throwing out a first pitch at Fenway. But I was horribly uncomfortable with that and didn't think I had done anything to deserve that and gave them a firm pass on that one."

After he left the service, Nick worked in baseball for the Angels, Dodgers and Mets. Ostensibly, he was a liaison to veterans. But what was being sold to the public as patriotism felt like commercialism. What Astore wrote outside of the game, Francona felt working within it. Camo jerseys. Corporate sponsorship of service, without the authenticity of service. The veterans felt like props.

"And, I mean, if you look at kind of the tone of what Memorial Day has become about, it’s pretty gross," Nick says. "Even on the teams’ official Twitter accounts — a flame emoji for, like, 'Look how hot these camo hats are.' And it's, like, 'Really, guys? That's the plan?' I mean, you can imagine how some of these Gold Star families reacted to that. They were not remotely amused.

"I might have asked the question 100 times and said, 'OK, if you’re selling a $40 hat, how much of this is going to charity, and where is it going?' I think it’s fair to say, if you’re an average fan watching Major League Baseball, you’re going to be, like, ‘Man, these guys are really supportive of the military.’ "

This support, Nick says, does not exist within MLB. According to the league’s figures, only 10 of the league’s 5,000 employees are veterans.

"That's genuinely difficult to accomplish," Nick says. "Like, if your goal was to hire as few veterans as possible, that's pretty impressive. I’m almost certain that there’s more than 10. But they’ve really gone out of their way to avoid being able to even identify the veterans. I’ve been arguing that for 10 years. Like, 'Figure out who they are, so we can support each other and link up and try to address some of these issues.' And they patently refused to be involved in that."

Working with the Mets, one moment defined his frustrations. He created a Memorial Day program where he matched players with Gold Star families from similar backgrounds. The players recorded videos that told the stories of the fallen.

Players, he says, were emotional learning the stories of the dead soldiers from America’s wars. They wore bracelets naming soldiers they were matched with. It was authentic and personal, appropriately respectful of a day commemorating sacrifice.

"So I’m on the flight back, and I get an email from someone with the Mets asking, like, 'Oh, great job. Now we need to get all the families to sign these waivers, to waive the rights as licensees for the bracelets that these guys wore.' And I’m, like, 'Whoa, whoa, whoa, we're not ... like, absolutely not.'

"They referred to them as 'license holders.' The families. And I'm, like, 'I think you mean parent of dead Marine or soldier.' Patently offensive. And there was no way I was going to have them sign that and refused to do so. I wanted to know exactly whose bright idea this was and was going to give them a piece of my mind. And that ended it pretty quickly. And the next day was my last day there.

"They called me in and said, ‘You’ve done a great job here, really had a huge impact. You’ve also had a big impact on the veteran stuff with Major League Baseball, but your comments aren’t compatible with having a career in baseball. So we're going to have to part ways.’ "

The Mets fired him. Nick Francona is now out of baseball.

"I’m certainly not happy about not working in baseball. It was my dream job, and I was good at it. And the people that fired me, ironically, told me I was very good at it. It sucks. Even thinking about it, I wouldn’t go back and say, 'I wish I had just compromised my principles a little more so I could succeed here.' Like, if that’s the price of success, I’ll find something else. I think it’s sad. And I think it speaks volumes about the state of Major League Baseball."

Recruiting is a main reason the military is embedded in sports. In an interview for my book, I told three-star General Russel Honore I didn’t want the Army recruiting my son while he watched the Red Sox. His response? “You better hold on to them, if you don’t want them in the Army. We’re gonna recruit the hell out of them. That’s how we man the force.”

"I appreciate the general's honesty," Astore says. "It's refreshing, in a way. But I just think that’s the wrong way to recruit.

"I lived in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, for nine years. Of course, that's the home of the Little League World Series. And one year, an Air Force van showed up. So kids, little leaguers, could come and go into this van and play video games. And the Air Force thought this was a great idea for recruitment. And I thought to myself, 'This is completely inappropriate.'

"I mean the Little League World Series should be for children. They're not even teenagers yet. And for baseball, yeah. It should not be an opportunity for any military service to show up and try to recruit youngsters.

"When I was interested in the military in high school, I went to see my civilian guidance counselor. There wasn't a Marine recruiter challenging me to a pull-up contest. So I see these kinds of things as a gradual process of the militarization of our society. And I just see it as something that we, as a democracy, should be guarding against."

Where do sports go from here? I asked one baseball executive, who told me his sport promotes the military not out of patriotism but out of fear — the fear of being called unpatriotic. Nearly 20 years after 9/11, Bill Astore believes these rituals have served their purpose.

"We sing 'God Bless America' during the seventh-inning stretch, because, well, that's what we do now," Astore says. "We have a huge flag and military flyovers because that's what we do. We celebrate a military person after the fourth inning because that's what we do. And we've come to expect it.

"I think we as Americans need to come together and recognize that all of this needs to be ratcheted back, that we need to return to a simpler time — when you played the national anthem, you respected our country and then you play ball. And you just enjoy the game the way it was meant to be enjoyed."

This segment aired on July 21, 2018.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License