Gregory Shupak

FAIR.ORG

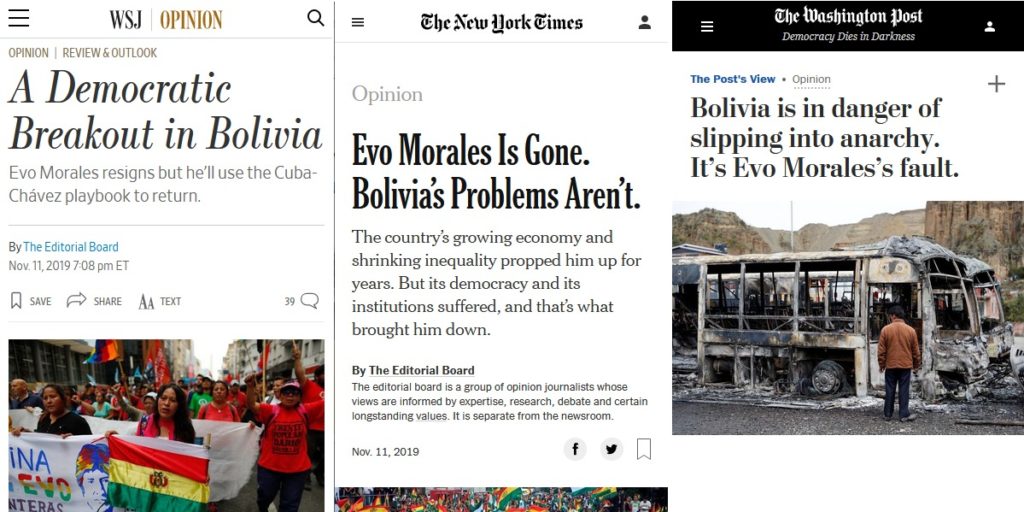

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]o endorse the coup in Bolivia, numerous editorials in major US media outlets paint President Evo Morales as undemocratic. Exhibit A in their case is the Organization of American States’ (OAS) claims that there was fraud in the October 20 Bolivian election in which Morales was elected for a fourth term. They also argue that he should not have been allowed to run again in the first place.

The New York Times’ editorial (11/11/19) accused Morales of “brazenly abusing the power and institutions put in his care by the electorate.” The Washington Post (11/11/19) alleged that “a majority of Bolivians wanted [Morales] to leave office”—a claim for which they provided no evidence—while claiming that he had “grown increasingly autocratic” and that “his downfall was his insatiable appetite for power.” The Wall Street Journal (11/11/19) argued that Morales “is a victim of his own efforts to steal another election,” saying that Morales “has rigged the rules time and again to stay in power.”

The first basis on which the papers call Morales’ democratic legitimacy into question is by suggesting that he had no right to run in the 2019 election because he lost a 2016 referendum on whether the country should abolish term limits. But the next year, Bolivia’s constitutional court lifted limits to re-election, and its Supreme Electoral Court subsequently approved Morales’ run. Even the head of the OAS, which would go on to play a crucial role in the coup, agreed that Morales had a right to run.

To support its assertion that Morales “had grown increasingly autocratic,” the Post linked to an AP report (Guardian, 12/17/16) that said Morales was going to run despite losing the referendum. That article was from before the two court rulings, and the Post doesn’t mention those decisions at any point. Thus readers were given the inaccurate message that the term limits story ended with the referendum.

The Times dismissed the court rulings by writing that “Morales had steadily concentrated power in his hands and planted loyalists in key institutions,” and that, following the term limits referendum, Morales “had the supreme court, by now stuffed with his loyalists, rule that limiting his time in office somehow violated his human rights.” Saying Morales “had” the court rule in a particular way implies that Morales forced it to reach that decision, but the paper provided no evidence to support that claim.

The Journal likewise described “a supreme court packed with his appointees [ruling that] he could run without term limits.” Words like “packed” and “stuffed” imply that it was unfair of Morales to do what democratically elected leaders in the United States, Canada and elsewhere have the right to do, namely appoint judges. That politicians use the power granted to them by winning an election to select judges who favor similar policies isn’t a sign of a nascent tyranny; it’s a sign of a politician working within the ordinary boundaries of representative, constitutional democracy. Besides, the country’s supreme court is elected, so it’s the Bolivian people who “packed” and “stuffed” the court with the judges that they voted for.

To suggest—as these papers do—that the Morales government’s maneuvers were indicative of a country descending into dictatorship is to overlook the ways in which the courts are consciously designed to function as checks on the popular will in liberal democratic states like the US and Canada. And if, as these paper seem to assert, the presence or absence of executive term limits is a definitive marker of democracy, then one assumes that there will soon be a deluge of editorials calling for coups in Canada and Britain, because these countries don’t have prime ministerial term limits (and the United States had no presidential term limits for most of its history).

If a sufficient number of Bolivians thought Morales’ candidacy was undemocratic, they could have voted him out in the October 20 election. There’s a paucity of evidence to believe that that’s what happened, but the editorials read as though it were a settled fact that the Morales government stole the election.

The official vote count conducted by Bolivia’s electoral authority found that Morales earned 47.08% of the vote, while Carlos Mesa finished second at 36.51%. To put Morales’ democratic legitimacy in context, Canada held a federal election the day after Bolivia in which Justin Trudeau became prime minister for a second term, even though his Liberal Party won 33.1% of the popular vote while the Conservatives got 34.4%, because of the way that Canada’s first-past-the-post electoral system distributes parliamentary seats. Bolivian law stipulates that a second round runoff is not required if the first place candidate secures at least 40% of the vote and 10 percentage points more than the second place candidate.

The editorials, however, called Morales’ victory into question by uncritically parroting OAS claims about Bolivia’s election. The Times refers to what it calls the “highly fishy vote on October 20,” linking that phrase to one of its earlier articles (10/23/19), which said:

The outcome of the vote has been in dispute since election officials released preliminary results on Sunday night that pointed to a runoff between Mr. Morales and Carlos Mesa, a former president—only to backtrack within 24 hours. On Monday night, election officials released an updated vote tally showing Mr. Morales leading by 10 percentage points, the margin required to avoid a runoff.

The October 23 article went on to write that elections observers from the OAS

issued a withering assessment of the integrity on the [electoral] process…. The mission said that the trend reversal between Sunday and Monday was at odds with independent tallies of the results and asserted that the outcome warranted a second round.

Much of the confusion—deliberate or otherwise—around the Bolivian election relates to the existence of two separate vote-counting processes: a “quick count” that is meant to be partial and provisional, and an official tally that necessarily takes longer, is comprehensive, and determines the actual results of the election.

A rigorous study conducted by the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) showed that the quick count—what the Times seems to be referring to as “preliminary results”—did not, in fact, “point…to a runoff,” and there was no “trend reversal.” CEPR pointed out:

It is a general phenomenon that later-reporting areas are often politically and demographically different from earlier ones, and it has been noted that this is relevant to interpreting the results from a parallel vote tabulation such as a quick count. In Bolivia’s elections over the last decade and a half, votes from rural and peripheral areas of the country have tended to disproportionately favor Morales and the MAS-IPSP. Because of logistical, technological and possibly other limitations, these votes end up being computed later in the counting process. This is true of both the quick and the official counts, which are both affected by the same geography and infrastructure. Rural and poorer places, which have tended to heavily favor Morales, are slower to transmit data or send tally sheets to the electoral tribunals….

The quick count, in this case, was no exception. The gap between Morales and Mesa widened steadily as the counting process advanced. It was a predictable and unsurprising phenomenon that need not have surprised the OAS mission….

In addition, and contrary to public statements from the OAS mission, an analysis of the results of the quick count up until it was suspended on election day predict an outcome that is extremely similar to the actual final results.

So the paper’s editorial endorsement of the coup because the election was supposedly “highly fishy” does not stand up to scrutiny. It’s not clear, moreover, what “independent tallies” the Times (10/23/19) thought were “at odds” with the Bolivian electoral commission’s count, or what evidence the paper thought there is for believing that the latter isn’t independent. Perhaps the paper means that the OAS should be seen as “independent”—but it hadn’t conducted a “tally” at that point and, as we’ll see, there is little reason to believe it’s “independent.”

Washington Post (11/11/19)

The Post went even further than the Times’ “highly fishy,” asserting that “the electoral tribunal, which [Morales] controls, then moved to falsify the results of the October 20 vote so as to hand him a first-round victory.” To provide backup for this argument, the Post linked to an earlier article (10/24/19) that said Morales “emerged from an unexplained gap in the publication of election results in better shape than he entered it.” Here the paper was presenting the unofficial quick count, where there was a gap—one that was, in fact, perfectly explicable—as though it and the official tally are one and the same. They’re not, and it wasn’t even the official count to which the OAS objected at the time. As the CEPR report noted:

It is the official count that is legally binding, not the quick count that the OAS mission took issue with. The official count was never interrupted and was regularly updated online without any significant interruption.

The Post article (10/24/19) then noted:

The chief elections observer for the Organization of American States said Wednesday that Bolivian authorities had no valid explanation for the gap in publishing vote counts. The OAS, which met in Washington on Wednesday to discuss the election, has called the gap “surprising” and “worrying.”

Gerardo de Icaza, the OAS director of electoral observation and cooperation, said the election should go to a second round, no matter the results of the first.

But there is a “valid explanation for the gap in publishing vote counts.” As the CEPR documents:

While the TSE did suspend the verification of tally sheets in the quick count process on election night at 83.85 percent of tally sheets verified, this is consistent with what the TSE had pledged to do more than a week before the election: to publicize the result of a quick count that verified at least 80 percent of the preliminary results. The TSE thus followed through with this commitment, and its decision to stop the quick count was not in itself irregular or in violation of any prior commitment.

Furthermore, the CEPR report points out that “although the TSE suspended the verification of tally sheets for the quick count, tally sheets continued to be imaged by electoral workers and uploaded to the storage server.”

The gap between this reality and the Post’s fictional picture of Morales “falsify[ing] the results” could scarcely be wider.

Wall Street Journal (11/11/19)

The CEPR’s findings deserved to be taken seriously and shared with a wide audience. Its report was available well before the coup, yet, in their apologies for Morales’ overthrow, the editorials write as though the CEPR’s damning critique of the OAS’s initial post-election complaint simply didn’t exist.

Hours before the coup, the OAS claimed that it conducted a preliminary audit that found “clear manipulation” of the election and called for the results to be annulled. Though Morales denied wrongdoing, he agreed to call a new election in keeping with his earlier promise—not exactly what would one expect of an “aspiring dictator,” as the Atlantic’s Yascha Mounk (11/11/19) baselessly called him. Neither the Times nor the Post mentioned in their pro-coup editorials that prior to the coup, Morales agreed to hold another election despite the lack of evidence that one was necessary: Such a detail would have complicated their portrayal of him as an antidemocratic despot.

The Times, Post and Journal’s post-coup editorials all uncritically parrot these allegations from the OAS. In doing so, the papers present the OAS as if it is a neutral arbiter of hemispheric affairs. It isn’t. Sixty percent of its funding comes from the US, which gives Washington disproportionate leverage over the organization. This is not just a theoretical possibility: there’s ample evidence in the OAS’s history of it acting in accord with US ruling class wishes to subvert democracy in Latin American countries that elected left-leaning governments. One crucial adjunct of American foreign policy, USAID, acknowledges OAS’s function, noting that the body is a crucial tool in “promot[ing] US interests in the Western hemisphere by countering the influence of anti-US countries” like Bolivia.

As historian Greg Grandin points out, the OAS approved of the US isolating Guatemala prior to the CIA’s 1954 coup against the elected government of President Jacobo Árbenz, and Cuba before the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion. The organization went on to endorse the US’s 1965 invasion of the Dominican Republic.

The OAS’s sordid history in Haiti offers another example: In 2000, the organization initially declared the country’s election a “great success” and then reversed course, helping set the stage for a coup against the democratically elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, after which thousands were murdered and officials of the constitutional government were jailed. In 2010, the OAS forced the reversal of the results of the first round Haiti’s election without conducting a recount or a statistical analysis.

The organization blessed Juan Orlando Hernández’s stolen election in Honduras and made no effort to stop Dilma Rousseff’s removal from power in Brazil.

Earlier this year, OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro encouraged the coup attempt in Venezuela by recognizing the unelected, self-declared “president” Juan Guaidó’s envoy as the nation’s supposed “official delegate” to the group—even though doing so violated the OAS’s own charter.

Considering OAS’s decades-long track record, and in particular considering the dubiousness of the OAS claims immediately after the election, the minimum media outlets should have done was share this information with readers, who might not have otherwise known there was reason to be skeptical of OAS claims. But that’s not what happened.

The Times’ post-coup editorial simply noted that hours before the coup, the OAS “declared that there was ‘clear manipulation’ of the voting.” The Post flatly stated that “an audit released by the Organization of American States reported massive irregularities in the vote count and called for a fresh election.”

The Journal, writing as though the OAS were irreproachable, said, “The Organization of American States (OAS), which monitored the election, said Sunday after a vote audit that it had found serious irregularities and ‘clear manipulation.’”

Asked for comment on that “preliminary audit,” CEPR senior fellow Andrés Arauz said:

The preliminary audit relies heavily on its identification of technical vulnerabilities and process concerns for both the quick and official counts, but fails to show that these were exploited for fraudulent purposes or that they may have had a significant impact on the final results of the election. While we are still in the process of examining their statistical analysis, it does not appear to show a change in the trend seen in the quick count results that can’t be accounted for by geography. This supposed change in trend was their basis for casting doubt on the integrity of the election in their first press release on October 21.

The Times, Post and Journal could have exhibited journalistic skepticism about the OAS’s statements on the day of the coup. Instead, they chose to embrace an anti-democratic, racist, US-facilitated and encouraged right-wing coup.

[premium_newsticker id="211406"]

Gregory Shupak teaches media studies at the University of Guelph-Humber in Toronto. His book, The Wrong Story: Palestine, Israel and the Media, is published by OR Books.

Gregory Shupak teaches media studies at the University of Guelph-Humber in Toronto. His book, The Wrong Story: Palestine, Israel and the Media, is published by OR Books.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.