Patrick Armstrong

– Fred Reed (who probably learned this in Vietnam)

According to a popular Internet calculation, the United States of America has not been at war with somebody for only 21 years since 1776. Or maybe it’s only 17 years. Wikipedia attempts a list. It’s a long one. You’d think that a country that had been at war for that much of its existence, would be pretty good at it.

But you’d be wrong. The “greatest military in the history of the world” has doubled the USSR’s time in Afghanistan and apparently it’s unthinkable that it should not hang in for the triple. Should the President want to pull some troops out of somewhere, there will be a chorus shrieking “dangerous precedent” or losing leadership and months later nothing much will have happened.

One cannot avoid asking when did the USA last win a war. You can argue about what “win” looks like but there’s no argument about a surrender ceremony in the enemy’s capital, whether Tokyo Bay or Berlin. That is victory. Helicopters off the Embassy roof is not, pool parties in a U.S. Embassy is not, “Black Hawk down” is not. Doubling the USSR’s record in Afghanistan is not. Restoring the status quo ante in Korea is not defeat exactly, but it’s pretty far from what MacArthur expected when he moved on the Yalu. When did the USA last win a war? And none of the post-1945 wars have been against first-class opponents.

And few of the pre-1941 wars were either. Which brings me to the point of this essay. The USA has spent much of its existence at war, but very seldom against peers. The peer wars are few: the War of Independence against Britain (but with enormous – and at Yorktown probably decisive – help from France). Britain again in 1812-1814 (but British power was mostly directed against Napoleon). Germany in 1917-1918, Germany and Japan 1941-1945.

Most American opponents have been small fry.

Take, for example, the continual wars against what the Declaration of Independence calls “the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions“. (Starting, incidentally, a long American tradition of depicting enemies as outside the law and therefore deserving of extermination.) The Indians were brave and skilful fighters but there were always too few of them. Furthermore, as every Indian warrior was a free individual, Indian forces melted away when individuals concluded that there was nothing in it for them. Because there were so few warriors in a given nation, Indian war bands would not endure the sort of casualties that European soldiers did. And, always in the background, the carnage from European diseases like the smallpox epidemic of 1837 which killed tens of thousands in the Western nations. Thus, whatever Indian resistance survived could usually be divided, bought off, cheated away and, if it came to a fight, the individual Indian nation was generally so small and so isolated, that victory was assured. The one great attempt to unite all the western nations was Tecumseh’s. He understood that the only chance would come if the Indians, one united force, showed the Americans that they had to be taken seriously. He spent years trying to organise the nations but, in the end, the premature action of his brother Tenskwatawa led to defeat of his headquarters base in 1811. Tecumseh himself was killed two years later fighting a rear-guard action in Ontario. It is because defeats of American forces were so rare that Little Big Horn has passed into legend; but the American casualties of about 250 would have been a minor skirmish a decade earlier. And the victory led to nothing for the Indians anyway; they lost the Black Hills and were forced into reservations. Brave and spirited fighters, but, in the end, no match for industrialised numbers.

The USA fought several wars against Spain and Mexico, gaining territory as it did. Despite the occasional “last stand” like The Alamo, these were also one-sided. The Spanish-American War is the outstanding example: for about 4000 casualties (half from disease), the USA drove Spain completely out of the Americas and took the Philippines, obliterating the Spanish Fleet at Manila Bay. More easy victories over greatly outmatched adversaries.

The other group of wars the U.S. was involved in before 1941 were the empire-gathering wars. One of the first was the takeover of the independent and internationally-recognised Kingdom of Hawaii; the sugar barons organised a coup against Queen Liliuokalani with the help of troops from U.S. warships and no shooting was necessary. Not so with the long bloody campaign in the Philippines, forgotten until President Duterte reminded the world of it. And there were many more interventions in small countries; some mentioned by Major General Smedley Butler in his famous book War is a Racket.

Minor opponents indeed.

Andrei Martyanov has argued that the U.S. military simply has no idea what a really big war is. Its peer wars off stage (since 1812) made it stronger; its home wars were profitable thefts. It believes wars are easy, quick, profitable, successful. Self delusion in war is defeat: post 1945 U.S. wars are failure delusionally entered into. To quote Fred Reed again:

The only exceptions are the Korean War – a draw at best – and trivial successes like Grenada or Panama. As I have argued elsewhere, there is something wrong with American war-fighting doctrine: no one seems to have any idea of what to do after the first few weeks and the wars degenerate into a annual succession of commanders determined not to be the one who lost; each keeping it going until he leaves. The problem is kicked down the road. Resets, three block war fantasies, winning hearts and minds, precision bombing, optimistic pieces saying “this time we’ve got it right“, surges. Imagination replaces the forthright study of warfare. Everybody on the inside knows they’re lost – “Newly released interviews on the U.S. war reveal the coordinated spin effort and dodgy metrics behind a forever war“; that’s Afghanistan, earlier the Pentagon Papers in Vietnam – but further down the road. When they finally end, the excuses begin: “you won every major battle of that war. Every single one”, Obama lost Iraq.

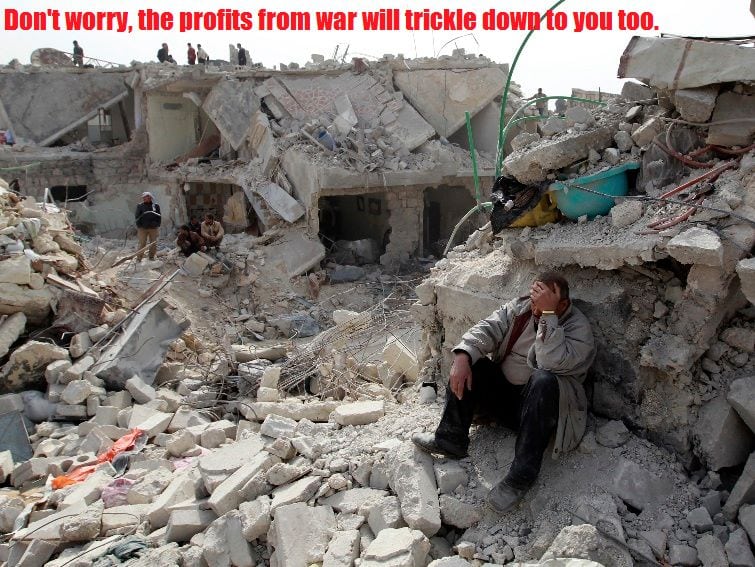

And always bombing. Bombing is the America way in war. Korea received nearly four times as much bomb tonnage as Japan had. On Vietnam the U.S. dropped more than three times the tonnage that it had in the whole of the Second World War. Today’s numbers are staggering: Afghanistan received, between 2013 and 2019, 26 thousand “weapons releases“. 26,171 bombs around the world in 2016 alone. Geological bombing. Precision attacks, they say. But the reality is quite different – not all of the bombs are “smart bombs” and smart bombs are only as smart as the intelligence that directs them. The truth is that, with the enormous amount of bombs and bad intelligence directing the “smart bombs”, the end result is Raqqa – everything destroyed.

If you want a single word to summarize American war-making in this last decade and a half, I would suggest rubble… In addition, to catch the essence of such war in this century, two new words might be useful — rubblize and rubblization.

The U.S. Army once really studied war and produced first-class studies of the Soviet performance in the Second World War. These studies served two purposes: introducing Americans who thought Patton won the war to who and what actually did and showing how the masters of the operational level of war performed. Now it’s just silliness from think tanks. A fine example of fantasy masquerading as serious thought is the “Sulwaki Corridor” industry of which this piece from the “world’s leading experts… cutting-edge research… fresh insight…” may stand as an amusing example. The “corridor” in question is the border between Lithuania and Poland. “Defending Suwalki is therefore important for NATO’s credibility and for Western cohesion” and so on. The authors expect us to believe that, in a war against NATO, Russia would have any concern about the paltry military assets in the Baltics. If Moscow really decided it had to fight NATO, it would strike with everything it had. The war would not start in the “Suwalki Corridor” – there would be salvoes of missiles hitting targets all over Europe, the USA and Canada. The first day would see the destruction of a lot of NATO’s infrastructure: bases, ports, airfields, depots, communications. The second day would see more. (And that’s the “conventional” war.) Far from being the cockpit of war, the “Suwalki Corridor” would be a quiet rest area. As Martyanov loves to say: too much Hollywood, too much Patton, too many academics saying what they’re paid to believe and believe to be paid. The U.S. has no idea.

And today it’s losing its wars against lesser opponents. This essay on how the Houthis are winning – from the Jamestown Foundation, a cheerleader for American wars – could equally well be applied to Vietnam or any of the other “forever wars” of Washington.

The resiliency of the Houthis stems from their leadership’s understanding and consistent application of the algebra of insurgency.

The American way of warfare assumes unchallenged air superiority and reliable communications. What would happen if the complacent U.S. forces meet serious integrated air defence and genuine electronic warfare capabilities? The little they have seen of Russian EW capabilities in Syria and Ukraine has made their “eyes water“; some foresee a “Waterloo” in the South China Sea. Countries on Washington’s target list know its dependence.

The fact is that, over all the years and all its wars the U.S. has rarely had to fight anybody its own size or close to it. This has created an expectation of easy and quick victory. Knowledge of the terrible, full out, stunning destruction and superhuman efforts of a real war against powerful and determined enemies has faded away, if they ever had it. American wars, always somewhere else, have become the easy business of carpet bombing – rubblising – the enemy with little shooting back. Where there is shooting back, on the ground, after the initial quick win, it’s “forever” attrition by IED, ambush, sniping, raids as commanders come and go. The result? Random destruction from the air and forever wars on the ground.

There is of course one other time when the United States fought a first-class opponent and that is when it fought itself. According to these official numbers, the U.S. Civil War killed about 500,000 Americans. Which is about half the deaths from all of the other U.S. wars. Of all the Americans killed in all their wars – Independence, Indians, Mexico, two world wars. Korea, Cold War, GWOT – other Americans killed about a third of them.

[premium_newsticker id=”211406″]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

ALL CAPTIONS AND PULL QUOTES BY THE EDITORS NOT THE AUTHORS

Read it in your language • Lealo en su idioma • Lisez-le dans votre langue • Lies es in Deiner Sprache • Прочитайте это на вашем языке • 用你的语言阅读

[google-translator]