By Jeff Mullen

PREFATORY NOTE

THIS IS A REPOST. • FIRST PUBLISHED ON 27 Nov 2011

- There are three basic wrongs with Libertarian ideology:

—The Non-Aggression Principle (NAP); —The false dichotomy of Reason and Force; — and presenting the theoretical construct of the Free Market as if it were reality. I shall address each of these in the following paragraphs. - The Non-Aggression Principle is very simple. Robert Murphy defines it quite well in a footnote on the top of page 9 in his work, "Chaos Theory: Two Essays on Market Anarchy."

- The NAP states that “no one has the right, under any circumstances, to initiate force against another human being, nor to delegate its initiation.”

- Libertarians go a step furhter: along with "another human being," they also add "or his property."

- That is to say, no matter how much wrong a person has done, no matter how much property a person has hoarded, and no matter how that person uses that property against other persons, one should NEVER initiate force against that person. Sorry, but if a serial killer was standing behind me, even if he only killed women (I'm a man), I would initiate force against him, and if a man used his property to rig the system and bilk me out of mine, I'd initiate force to make sure that I got enough to survive, even if that man's actions were entirely within the scope of the letter of the law. This is not unreasonable. Thus, I cannot take this pledge--and, if you think about it, you shouldn't either.

- The False Dichotomy of Reason and Force is also easy to state:

- Libertarians claim that there are only two ways to get someone to do what you want him to: reason and force. You can convince him or you can force him.

- That statement is false. Actually, there is a third: bribery. You can convince him, you can threaten him or you can bribe him. Force is actually a form of punishment.

- Libertarians, however, do not stop with this false statement. In a process that I call "hyperspace resoning," because it has nothing to do with normal reality, they use this false statement as a premise for other, greater falsehoods. Specifically, they use the following:

- All payment is a form of reason and all legislation is a form of force. Thus, if I pay someone to con people out of their property, even if he uses statements that he knows are lies and go against his personal beliefs in the process, I'm REASONING with him! Likewise, Pell Grants, which are legislated, must "force" people to go to college.

- Actually, payment is a form of reward and legislation is a framework through which reward and punishment may be administered in a manner that appears to be more or less reasonable.

- Libertarians go one step farther out of reality:

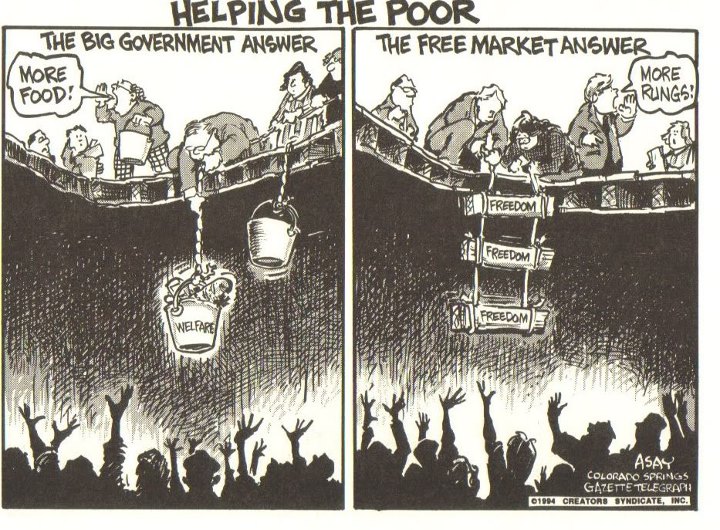

- Corporations, which issue payment, are always good; the government, which issues legislation, is always bad.

- Thus, by starting with falsehood and piling more falsehood on top of it, Libertarians come up with something that is completely absurd.

- The "Free Market"

- When pressed to defend their religious belief that Government is ALWAYS bad and Business is ALWAYS good, Libertarians will resort to a trick definition. They will say that it is not Business, per se, that is always good, but a "Free Market." A business ceases to be part of the "Free Market" when it "consorts with Government." Thus, the Free Market is always good, so, if someone in it does something bad, they're not part of the Free Market any more. The same Free Market is supposed to have ways of naturally preventing government/business collusion, but, somehow, it persists!

- This is impossible because, in reality there is no such thing as a free market. It is an idyllic theory, one that flies in the face of reality. Bad things happen, and Government and Business, as institutions of power, combine and collude.

- The Idyllic Theory of the Free Market differs from reality in that, in order to function as they say it does, it requires two impossible precondtions. First, it requires Perfect Knowledge: all parties to a transaction have to have a complete and full depth of understanding of that transaction. Second, it requires Perfect Competition: all of the buyers and all of the sellers within a Free Market have to compete, there can never be a combination in restraint of trade and no monopoly. [Editor's Note: These fantastic assumptions continue to be taught in standard microeconomics courses as a legitimate description of market behavior.]

Let's illustrate this point. In his work, "Chaos Theory: Two Essays on Market Anarchy," noted Libertarian Robert Murphy describes the Free Market policing itself as follows:

Suppose that a big firm bribed the arbitrators at Agency X, so that lazy workers (who were going to be fired anyway) were (falsely) charged by the employers with embezzlement, while Agency X always ruled “guilty.” With this scheme, the big firm could bilk thousands of dollars from its bad employees before terminating them. And since the hapless employees had agreed beforehand to abide by the arbitration outcome, they could do nothing about it.

But upon consideration, it’s easy to see that such behavior would be foolish. Just because an arbitration agency ruled a certain way, wouldn’t make everyone agree with it, just as people complain about outrageous court rulings by government judges. The press might pick up on the unfair rulings, and people would lose faith in the objectivity of Agency X’s decisions. Potential employees would think twice before working for the big firm, as long as it required (in its work contracts) that people submitted to the suspect Agency X.

Other firms would patronize different, more reputable arbitration agencies, and workers would flock to them. Soon enough, the corrupt big firm and Arbitration Agency X would suffer huge financial penalties for their behavior. Under market anarchy, all aspects of social intercourse would be “regulated” by voluntary contracts. Specialized firms would probably provide standardized forms so that new contracts wouldn’t have to be drawn up every time people did business. For example, if a customer bought something on installment, the store would probably have him sign a form that said something to the effect, “I agree to the provisions of the 2002 edition Standard Deferred Payment Procedures as published by the Ace legal firm.”

Before we continue, it must be noted that, even if Murphy's little thought experiment worked like actual reality--which it does not--in his scenario, the employees who are bilked out of their money never get it back. There is no admission of guilt on the part of the employer, no direct punishment for his wrongs and no restitution. On this basis alone, Murphy's system (the "Free Market") fails.

Let's let the man's anti-labor bias (lazy employees who were going to be fired anyway?) slide. Now, it's time to compare his theory to reality.

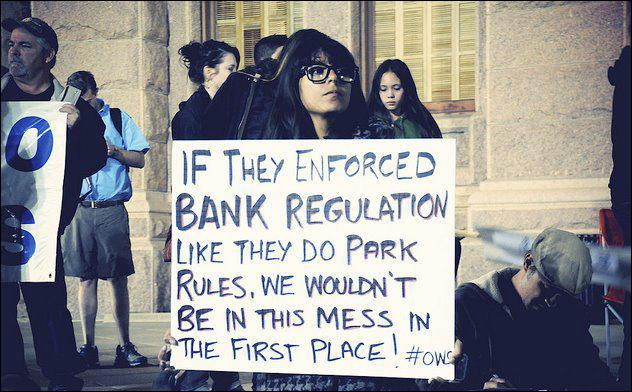

In April of 2011, the Supreme court struck a blow against consumers by deciding that people who sign agreements with arbitration clauses, as referred to above, are no longer allowed to file class action suits if the arbitration goes horribly against them. The name of the case is AT&T Mobility v. Concepcion. You can find a commentary on that decision in the addendum.

Here are some selected comments on how those contracts really work, abstracted from that article.

Consumers are effectively forced into signing a contract in order to receive cellular service. [There is a] strong likelihood of strong-arm attempts by wireless providers against the embattled consumer.

The provisions are rarely read and most laypersons do not fully understand the implications of agreeing to settle all disputes with an arbiter as opposed to a judge.

In reality, there is a very strong likelihood that the prudent consumer is not going to expend money for an attorney and the incidental costs of arbitration over a $30 fee. They are as well ineligible for small claims court as they signed an agreement to submit to arbitration. Thus, consumers are effectively stopped from realizing any real recovery for their claims. So much for the claims to fairness of the free market.

In reality, the arbitration agency favors the corporation at the expense of the customers, the press got a hold of it and it didn't make a bit of difference, all the corporations are de facto colluding with their boilerplate contracts, favoring the unfair arbitration agencies and the consumers really don't have the resources to change this. This is almost entirely the opposite of how Murphy says the system is supposed to work. That is because it is the Real Market, not the Free Market.

Succinctly, the Real Market works nothing like a Free Market. Murphy's thought experiment is a ridiculous sham. Yet, Libertarians persist in arguing their theory against reality, even though it has been shown to be wrong time and time again.

Many of the most repulsive politicians in the US proclaim (proudly) their allegiance to libertarianism. Paul Ryan, a vile scoundrel by any standard, is one of them.

In order for this system to function properly, it would be necessary for the customers to know everything about the transaction--including the ruling records of the arbitrators--which, it has been pointed out, most customers do not regard as being worth the effort to find out. It would also be necessary for some wireless companies to offer the services of arbitrators who were not completely favorable to their cause. This, again, seldom if ever happens, according to the courts. Thus, the Real Market does not behave at all like the Free Market. (Imperfect information flaw.)

Note also that, in this case, the "colluding with the government" argument doesn't really work. The court case decided that the government (the courts) should NOT intervene either for the company or the customers, and this harms the customers far more than the company. Its result is LESS interaction between government and corporation. Yet, this favors the corporation, not the customer. It is not collusion with the governemnt that causes problems in the market, it is attacks on the consumer, with or without government/corporate collusion.

In the 1980's, the Neoconservative Movement of the Republican Party used language borrowed from the Libertarians to rise to power. While this language sounds good when first listened to, scrutiny reveals that it is little more than nonsense. This piece of writing has discussed the false statements and rhetorical trickery that lie at the heart of Libertarian belief. With this information, one can argue more effectively against the neurotic religion of the Libertarians.

ADDENDUM

Prepared by Ledger & Associates

Consumers Take a Hit as Supreme Court Rules No Class Action Status for Cellular Subscribers

Editor's Note: Bourgeois culture cultivates the myth that the law is majestically impartial to all parties, immutable, and above shifting political tides. In so doing it denies the obvious, that the law is not only a mere reflection of the prevailing values of a given society at a certain point in time, but deeply rooted in the economic and political interests of the dominant class, in the case of the United States, and much of the capitalist world, the reigning corporate plutocracy. The decision featured below, and a number of others, have increasingly confirmed that this is indeed the case. Today, the Roberts Court is by any measure one of the most politicized and reactionary courts in American history, and its findings can be almost depended on to be injurious to the public.—PG

•••

The United States Supreme Court ruled this week that AT&T subscribers are ineligible for class action status and all disputes are governed by the boilerplate language found in the original contracts between consumers and their cellular provider. California plaintiffs were seeking to establish class action status and sue AT&T over a variety of problems with the wireless service. This ruling came in opposition of a California state court holding that plaintiffs can band together in a class and recover a $30 fee assessed on the sale of a phone that was advertised as completely free.

Procedurally, California’s courts ruled in favor of plaintiffs who contended that AT&T’s boilerplate arbitration agreements did not control and disgruntled AT&T customers could sue in a court of law. The court opined that since consumers are effectively forced into signing a contract in order to receive cellular service, they should not be prohibited from filing class action lawsuits against massive wireless corporations. These decisions were reached keeping consumers in mind and recognizing the strong likelihood of strong-arm attempts by wireless providers against the embattled consumer.

Unfortunately, the Supremes saw it another way. In an opinion authored by Justice Scalia, boilerplate arbitration language is binding on the consumer despite the fact that the provisions are rarely read and most laypersons do not fully understand the implications of agreeing to settle all disputes with an arbiter as opposed to a judge.

This holding flies in the face of consumer advocacy groups who proclaim that consumers are forced between a rock and a hard place. In reality, there is a very strong likelihood that the prudent consumer is not going to expend money for an attorney and the incidental costs of arbitration over a $30 fee. They are as well ineligible for small claims court as they signed an agreement to submit to arbitration. Thus, consumers are effectively estopped from realizing any real recovery for their claims. These advocacy groups contend that class actions were designed for this type of problem and by stripping consumers of the right to form a class action they are left with no opportunity for recovery.

Curiously, this precedent hardly fits with previous holdings requiring four mega-carriers to refund millions of dollars in early termination fees. Similarly, Verizon was forced to refund users for unfounded data charges. It would be interesting to see how those cases would fare under the latest consumer law precedent.

Dissenters opined that this case has less to do with upholding vague arbitration clauses and more to do with prioritizing traditional state law values over man-made contract law.

Class action lawsuits have been helpful to consumers across the nation. In order to qualify for class action status, plaintiffs must successfully argue that they are all similarly situated with comparable injuries caused by the same product or service. Courts will often grant class action status in consumer fraud or products liability cases. Denial of class action status means that each plaintiff must sue separately. In this case, each plaintiff is prevented from suing because each signed an agreement to submit to arbitration.

_________________

¶

ADVERT PRO NOBIS

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IF YOU THINK THE LAMESTREAM MEDIA ARE A DISGRACE AND A HUGE OBSTACLE

to real change in America why haven’t you sent at least a few dollars to The Greanville Post (or a similar anti-corporate citizen’s media?). Think about it. Without educating and organizing our ranks our cause is DOA. That’s why our new citizens’ media need your support. Send your badly needed check to “TGP, P.O. Box 1028, Brewster, NY 10509-1028.” Make checks out to “P. Greanville/ TGP”. (A contribution of any amount can also be made via Paypal and MC or VISA.)

THANK YOU.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Trying to “prove” things about politics and economics is similar to the situation of geometry. People already have some idea of what they believe is “true,” and then they draw connecting lines between those “true” statements and they believe they’ve formed a proof. I think the greatest difference between libertarians and socialists (what I guess I am) is a matter of attitude: Ask people how they feel about sharing, or how they feel about private property. It’s not a question of fact or theory. Though you may have difficulty getting a straight answer from a libertarian — not because they… Read more »

Comments removed again? You guys really don’t believe in free speech, do you? You intend to leave the article’s false statements without any correcting responses. What’s wrong with leaving the comments there and letting your readers decide for themselves? Most of them are going to agree with the author of the article and disagree with my comments, but at least they could see why I think the author has made some mistakes.