|

The story of earlier imperial civilizations holds cautionary lessons about our own trajectory and hidebound arrogance. In antiquity (and this is disputed) only the Roman empire seems to have reached half a millennium. In modern times, despite their global footprint and technological prowess, no European empire has survived in full dominance beyond 250 years, and even the almighty US empire is showing signs of dysfunction and collapse in less than 150. Imperial trajectories are normally marked by lucky serendipity, accomplishments, narcissism, hubris, overreach, internal decay, and plenty of savage criminality—in the open or disguised, as is the favorite mode in our so-called democracies. Eventually, the rot within proves to be the decisive morbidity. In this post, we take a look at the Assyrian empire. We offer three views. What do you think? Appearing in The Guardian,

|

[premium_newsticker id="211406"]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

You have to hand it to the ancient Assyrians – they were honest. Their artistic propaganda relishes every detail of torture, massacre, battlefield executions and human displacement that made Assyria the dominant power of the Middle East from about 900 to 612BC. Assyrian art contains some of the most appalling images ever created. In one scene, tongues are being ripped from the mouths of prisoners. That will mute their screams when, in the next stage of their torture, they are flayed alive. In another relief a surrendering general is about to be beheaded and in a third prisoners have to grind their fathers’ bones before being executed in the streets of Nineveh.

These and many more episodes of calculated cruelty can be seen carved in gypsum in the British Museum’s blockbuster recreation of Assyria’s might. Assyrian art makes up in tough energy what it lacks in human tenderness. It is an art of war – all muscle, movement, impact. People and animals are portrayed as fierce cartoons of merciless force.

‘Celebrating the blood-sport of the king’ … Ashurbanipal on a hunt. Photograph: Matt Dunham/AP

Yet behind the conquests these eye-blistering reliefs depict, lay an intricate system of bureaucracy and a passion for logistics. I Am Ashurbanipal is a portrait of the banality of empire. Just as Hannah Arendt argued that the Holocaust was perpetrated by characterless paper-pushers, not flamboyant sadists, so we find here that Assyrian atrocities – including the forced resettlement of thousands of Israelites – were not the product of random mayhem but diligent organisation.

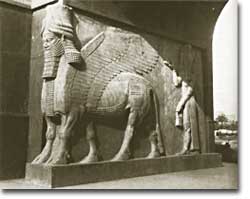

The Assyrian empire was so disciplined that even though this exhibition focuses on one man, Ashurbanipal, who ruled the empire from 669BC until his death somewhere around 631BC, his personality is as remote as the sphinxes and lion spirits that loom in the atmospherically lit galleries. Ashurbanipal is less an individual in this show than a set of royal roles that he seems to have carried out immaculately. A letter that he wrote to his father when he was 13 – did the boy ever see his dad? – describes how he has been learning all the proper skills for a king.

One was hunting. In stone relief after stone relief, the blood-sport of the king is celebrated. Unusually, Ashurbanipal and his family didn’t hunt harmless deer or lumbering wild boars. They fought lions, to prove their superhuman virility and capacity to subdue the savage. Lions, portrayed with great observational accuracy, are shown being shot at close range with arrows or speared in the neck, their bodies carried aloft by servants. It’s a more equal battle than some the Assyrians conducted against human enemies and fought, it seems, with more respect. Lions rear up against their attackers and try to face down men on horseback. There’s a study of a dying lion gushing blood.

Ashurbanipal, shown with cuneiform inscription. Photograph: The Trustees of the British Museum

This excellent organisation, it seems from this detailed delve into history, was the true originality of the Assyrian Empire. It was precociously modern in its organisational rigour. Ashurbanipal was not a romantic conqueror like Alexander the Great or Daenerys Targaryen. He was the CEO of a ruthless global enterprise. Perhaps it is weirdly fitting that the exhibition is sponsored with much fanfare by BP. The controversial oil company is part of the relentless machinery of the modern world that exploits nature even faster than Ashurbanipal killed lions.

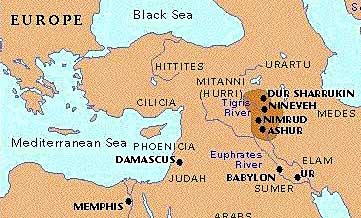

You can’t get away from the 21st century in this unsettling and even nightmarish exploration of the rise and fall of empires. The mini “caliphate” created by Islamic State was nothing like as vast or enduring as the Assyrian empire but in the three years that they ruled Mosul in Iraq, from June 2014 to July 2017, Isis militants set out to destroy the remains of Ashurbanipal’s pre-Islamic culture. The ruins of Nineveh, capital of the Assyrian Empire, are on Mosul’s outskirts. They smashed antiquities in the Mosul Museum and set about demolishing Nineveh itself.

‘A glimpse of hope’ … stone tablets from the library of Ashurbanipal. Photograph: Matt Dunham/AP

What’s it all for? Human history, including that of our own times, looks pretty brutal in this exhibition. One of the palace reliefs portrays people defeated by the Assyrians being forced by Ashurbanipal’s soldiers to migrate to land where their labour will profit the empire. Scenes like this are both fascinating and utterly crushing to the human spirit. The efficient brutality of the Assyrians looks like a sterile enterprise that existed only, at least as far as this exhibition goes, for the glory and luxury of the monarch. Once Ashurbanipal was dead, his empire fell apart. A wall-filling film of a city in flames looks as if it might be Mosul in 2017 or during the Iraq war. In fact it is meant to suggest the burning of Nineveh in 612BC and the apocalyptic end of Assyrian power.

Yet in this futile cycle of rising and falling empires one glimpse of hope gives the exhibition warmth. It is a wall of illuminated cuneiform tablets, their spiky scripts full of words that only specialists can read but whose human weight anyone can feel. These clay tablets come from the great library Ashurbanipal created in Nineveh. It was his enduring contribution to civilisation. The library was fired in the destruction of Nineveh at the end of the seventh century BC, but clay tablets don’t burn. They were hardened and preserved by the heat.

They include the text of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Collected by Ashurbanipal and excavated from his library, this is the best-preserved copy of the world’s earliest literary masterpiece. It’s still a basis for modern translations. Ashurbanipal may have been a murderous bureaucrat but he was also a benefactor of civilisation. In the relentless cycles of history, that urge to preserve and remember is what raises us out of the dust.

I am Ashurbanipal is at the British Museum, London, from 8 November to 24 February.