Class Uber Alles: Meet Reinhard Gehlen, Hitler’s Favorite Spy Who Used CIA Resources To Free Nazi War Criminals

By Morgan Dunn | Checked By Leah Silverman

ALTHATSINTERESTING.COM

Gehlen's triumphant incorporation into the top power structure of "the West"—the so-called capitalist democracies—represents chilling proof that no matter their rhetoric, class interest comes first for the ruling oligarchy.

First published November 9, 2020

An expert spymaster, Reinhard Gehlen surrendered to the Allies at the end of World War II in order to work with the CIA before founding Germany’s modern intelligence service with hundreds of former Nazis like him.

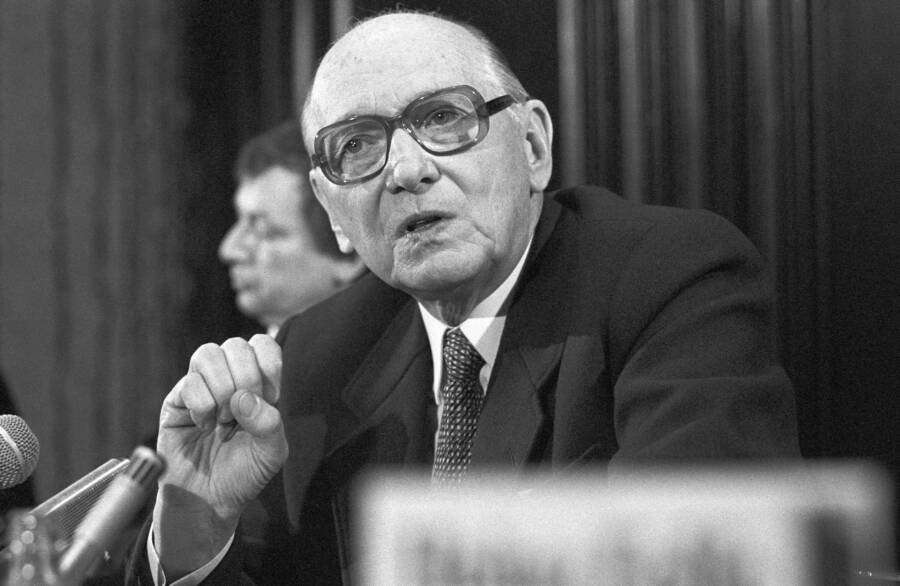

Reinhard Gehlen, seated front row with an “O” over his chest, was well-respected among Nazi leaders. He later used this experience to start one of the most notorious spy rings in the Cold War.

At midnight on May 8, 1945, Nazi rule came to an end in Germany. The date, now called Stunde Null or “Zero Hour,” remains one of the most significant moments in modern German history.

The crushing defeat of Nazi Germany by the Allies took many Germans by surprise. But others in the country had weighed the possibility of their demise and made their own preparations to ensure that no matter the victor, Nazi rule could again rise from the ashes of their failed nation.

Reinhard Gehlen was one such individual.

An espionage expert and a political opportunist, Gehlen made plans to ensure that the Third Reich would live on after Stunde Null and he created a network of ex-Nazi spies that would go on to form the modern German intelligence community — and he did so in part by scamming the CIA.

Reinhard Gehlen Was An Invaluable Nazi Spy

Reinhard Gehlen is seen here with fellow officers at a camp used to recruit, or coerce, Russian POWs into the so-called Russian Liberation Army. (Ullstein bild/Ullstein bild via Getty Images)

Reinhard Gehlen was born into a family of loyal Prussian militarists on March 3, 1902. Most men in his family had been career army officers for Germany, and Gehlen followed a similar path. As soon as he passed his exams, he was commissioned into the Reichswehr, or Reich Defense, under the Weimar Republic leading up to the rise of Hitler.

Gehlen was reportedly quiet among his fellow soldiers, but nevertheless, he proved himself with his exceptionally sharp mind for facts, figures, and organization. In 1935, he was promoted to captain and assigned to the German General Staff. Here, he developed his skills for fieldcraft and espionage.

As Hitler’s armies sprawled across the Russian countryside, the German Army’s military intelligence unit on the Eastern Front donned combat gear and disguises to penetrate far behind Russian lines, gathering valuable intelligence.

In 1942, Major Reinhard Gehlen was promoted to commander of the Fremde Heere Ost (FHO), or Foreign Armies East, which was a military intelligence organization dedicated to penetrating Russian lines as the Third Reich dominated Europe.

A fervent anti-Communist, Gehlen threw himself into his work and produced key reports which led to Germany’s early successes in pushing the Soviet Union out of its territory.

But even as early as 1942, when Hitler was rapidly becoming a dictator of Europe, Gehlen began to mull the possibility of his country’s defeat. As the tide of World War II shifted and the Allies gradually beat back the Nazis, Gehlen drew up reports that revealed the failures of the German military. These matter-of-fact analyses infuriated Adolf Hitler, who called Gehlen’s findings “defeatist.”

In April 1945, Hitler’s empire crumbled around him and he fired Gehlen, who at the time was his most capable spy. Gehlen, now a major general, shrugged off the dismissal and continued his work copying every scrap of intelligence about the Russians he could find.

According to his 1972 memoir, The Service, mere days before the Allies moved into Germany, Gehlen and his devoted officers buried 52 steel drums packed with microfilm that contained the results of six years worth of espionage work.

He then ordered his men to wait for his signal and quietly surrendered himself to United States troops.

Cooperating With And Exploiting The CIA Through The Gehlen Org

After interviewing with high-ranking American officers, Reinhard Gehlen brokered a deal with them that protected him from being prosecuted for war crimes in exchange for collecting intelligence on the Soviets for the U.S.

By the end of 1946, the U.S. Army provided Gehlen with funding to build the so-called Gehlen Organization, or “Org,” which Gehlen populated with 350 ex-Nazi officers, some of who were considered war criminals.

Gehlen and his cronies were then allowed to pursue their own agenda on both sides of the West German border — and all under the authority of U.S. Army intelligence. In 1949, the CIA officially absorbed Gehlen’s group and gave them $5 million a year for their own intelligence projects.

Although The Org had value to the American intelligence community, the U.S. Army was nonetheless desperate to be rid of it. Not only was The Org quickly riddled with Soviet moles shortly after its inception, but American officers were wary of Wehrmacht and SS veterans.

Indeed, at least five associates of Adolf Eichmann, the “Architect of the Holocaust” who designed the systematic genocide of European Jews, worked for the CIA. The CIA allegedly also approached 23 other Nazis for recruitment, and at least 100 officers within the Gehlen Org were former SD or Gestapo officers.

The Army struggled to control the group as Gehlen’s men continued to pursue their own agendas, like helping other Nazi war criminals flee Europe via an underground escape network that included transit camps and fake ports supplied by the CIA. The CIA-funded side project helped over 5,000 Nazis flee Europe to South and Central America.

CIA Director Richard Helms opposed the adoption of the Gehlen Organization by the CIA, noting “serious flaws in the security of the operation.”

“We did not want to touch [the Gehlen Organization],” noted Peter Sichel, the CIA chief of German operations. “It had nothing to do with morals or ethics, and everything to do with security.”

Although the CIA distrusted Gehlen, their temptation to strike a blow at Moscow grew, and Gehlen assured American intelligence officers that he could succeed where they had failed. “Given how hard it was for us,” one CIA operative noted, “it seemed idiotic not to try it.”

For eight years, Gehlen gathered some reliable intelligence from wartime informants in Eastern Europe. He also had some success with infiltrating East Germany and collecting valuable information about the Soviet’s military units for the Americans.

But overall, the Gehlen Org often had to resort to fantasy to keep the CIA satisfied with their work. They concocted wild stories based on “confessions” given by POWs returning from the Soviet Union, and told stories about advanced military technology and a nuclear program far ahead of the West’s.

Faced with this phantom of a massively powerful Soviet Union, American intelligence agents felt they had no choice but to stick with their German spies, despite whatever reservations they may have had about the men who populated its ranks.

Heinz Felfe, former German intelligence agent and Gehlen’s longtime adjutant, was so brazen about his role as a Soviet spy that he would use the radio transmissions containing his orders to instruct new recruits to the Federal Intelligence Service. (Mehner/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

Founding Germany’s Version Of The CIA

In 1956, the Gehlen Organization was legitimized as the new Bundesnachrichtendienst, or “Federal Intelligence Service,” which was and remains Germany’s equivalent of the CIA. But the triumph would not last.

By 1968, numerous Soviet moles were exposed within the group and many of them had purportedly worked with Gehlen for decades. The moles even included Heinz Felfe, Gehlen’s longtime deputy. The shocking revelation resulted in Gehlen’s dismissal.

While other ex-Nazis were jailed and tried for their crimes, Reinhard Gehlen succeeded in avoiding capture or prosecution. Although well-known in intelligence circles, Gehlen escaped notice, and died quietly in 1979.

Up until the end of his life, Gehlen enjoyed the protection of German and American leaders. They were willing to overlook his Nazi past in order to use his skills. As the German newspaper, Der Spiegel, noted decades after Gehlen’s death: “If there was ignorance on the matter, it was only because no one wanted to know.”

After learning about Reinhard Gehlen, learn about more of Hitler’s top men including Reinhard Heydrich, the “Man with an Iron Heart” who was too cruel even for the Führer. Then, learn about Claus von Stauffenberg, the German officer who tried to halt the nightmare of Nazism by assassinating Hitler.

If you find the above useful, pass it on! Become an "influence multiplier"!

The battle against the Big Lie killing the world will not be won by you just reading this article. It will be won when you pass it on to at least 2 other people, requesting they do the same.

| Did you sign up yet for our FREE bulletin? It's super easy! Sign up to receive our FREE bulletin. Get TGP selections in your mailbox. No obligation of any kind. All addresses secure and never sold or commercialised. [newsletter_form] |

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License