the establishment media is an enabler of endless wars and illegitimate oligarchic power

the establishment media is an enabler of endless wars and illegitimate oligarchic power

80 years ago, December 7, 1941…Pearl Harbor, a Surprise Attack?

By Jacques Pauwels

By Jacques Pauwels

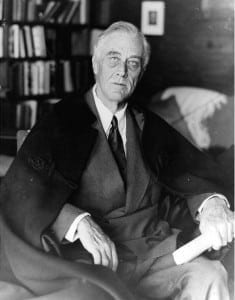

Myth: The United States became actively involved in the Second World War because of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. For some time already, President Roosevelt had been eager to go to war against Nazi Germany but was unable to do so because Congress was dominated by isolationists. However, after the treacherous Japanese surprise attack against Pearl Harbor, Congress reversed its stand and agreed to declare war on Japan, which also meant war against the German ally of the Land of the Rising Sun.

Reality: The political and military leaders of the US, including President Roosevelt, did not want war against Nazi Germany, but certainly did against Japan. Uncle Sam had been preparing for such a war for a long time already and looked forward to winning quickly and easily. They deliberately provoked Tokyo into attacking Pearl Harbor, so the conflict could be presented to Congress and the American public as a purely defensive one. After this attack, Congress declared war on Japan but not on Nazi Germany, which had nothing to do with this aggression. It was Hitler who, totally unexpectedly, declared war on the US, even though he was not required to do so according to the terms of his alliance with Japan. The US thus also found itself at war against Germany, something that had not been foreseen and for which no plans had been prepared.

The Great Depression of the “dirty thirties” was essentially a crisis of overproduction combined with insufficient demand. In the US, President Roosevelt tried to stimulate demand with a combination of “Keynesian” measures, including public works, collectively known as the New Deal: “make-work” schemes were supposed to create jobs, thus increasing aggregate purchasing power. The construction of dams has received as much publicity in this respect as that of motorways in Hitler’s Germany but, again as in the case of Germany though admittedly to a lesser extent, major armament projects, e. g. the construction of aircraft carriers and bombers, also stimulated production, profits, employment, and ultimately increased demand.

However, it was the war itself that caused the American economy to exit the crisis and experience an unprecedented boom. Airplanes, ships, tanks, trucks, and all sorts of other martial equipment henceforth needed to be produced not only for Uncle Sam himself but also - via the Lend-Lease program of loans - first to Britain and her allies and eventually even to the Soviet Union. And we should not forget that, at least until Pearl Harbor, US oil trusts also profited from sales to all belligerent countries, including Germany.

And so, thanks to the war in Europe, the US emerged from the nightmare of the Great Depression. Production and employment were skyrocketing, and so were profits. In this context, corporate America also looked elsewhere in the world for markets for its finished products, opportunities for the lucrative reinvestment of the capital that was accumulating, and, last but not least, raw materials such as rubber and petroleum.

Half a century earlier, at the end of the 19th century, the US had joined the world’s other great industrialized and capitalist countries in a very competitive worldwide “scramble” for markets and resources, thus becoming an “imperialist” power like Great Britain and France. Via an aggressive foreign policy, pursued by presidents such as Theodore Roosevelt, a cousin of FDR, and a “splendid little war” against Spain, America had acquired control over former Spanish colonies such as Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippines, and over the hitherto independent island nation of Hawaii. Uncle Sam thus became very interested in the Pacific Ocean, its islands, and the lands on its far shores, the Far East. Particularly attractive over there was China, from a businessman’s point of view a “market” with unlimited potential, and a huge but weak country seemingly ready to be penetrated economically by an imperialist country with enough power and ambition to do so.

In the Far East, and particularly with respect to China, the US faced the competition of an aggressive rival power that sought to realize its own imperialist ambitions in that part of the world, namely Japan, the Land of the Rising Sun. Relations between Washington and Tokyo had not been good for decades, but worsened during the Depression-ridden 1930s, when the competition for markets and resources was heating up. Japan was even more needy for oil and similar raw materials to feed its factories and for markets for its finished products and its investment capital. Tokyo went so far as to wage war on China and to carve a client state, Manchukuo, rich in raw materials, out of the northern part of that country. What bothered the US was not Japanese aggression against China and oppression and exploitation of the Chinese, but Tokyo’s increasingly obvious determination to turn China and the rest of the Far East, including resource-rich Southeast Asia and Indonesia, into an economic bailiwick of their very own, a “closed economy” in with there was no room for the American competition (Hearden, p. 105).

Like their country’s upper class in general, American businessmen were extremely frustrated at the prospect of being squeezed out of the lucrative Far Eastern market by the “Japs,” a supposedly inferior “yellow race” Americans in general had already started to despise during the 19th century – as much as the “Chinks,” as they called the Chinese. (Having lumped together the Japanese and the Chinese as racially inferior folks representing a “yellow peril,” the Americans would find it difficult during the war to explain to their soldiers and civilians the difference between their Chinese allies and their Japanese foes.) (“Anti-Japanese sentiment”).

With the eruption of war in Europe, an important new factor came into play. The defeat of France and the Netherlands in 1940 at the hands of Nazi Germany raised the question of what would happen to their colonies in the Far East, namely Indochina, rich in rubber, and Indonesia, blessed with petroleum. Since their mother countries were occupied by the Germans, these colonies looked like delicious low-hanging fruits, ready to be picked by one of the remaining competitors in the game of the great powers — but which one?

The Germans certainly did not lack the appetite, but they would first have to win the war in Europe and impose a Versailles-style settlement on the losers. But the prospects of a German triumph were fading fast as early as the summer of 1941, when the Wehrmacht’s “lightning-fast warfare” (Blitzkrieg) against the Soviet Union failed to achieve a “lightning-fast victory” (Blitzsieg), a triumph that was expected, and indeed extremely likely, to have turned Nazi Germany into an invincible Behemoth. As for the British, they continued to have their hands full with the war against the Reich, and they had reason to fear for their own imperial possessions in the Far East, such as Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Singapore.

A very likely candidate, however, was Japan, a power with great ambitions, especially in its own part of the world, and a keen appetite for rubber and oil. Could the US tolerate a Japanese expansion into Southeast Asia in addition to a Japanese monopoly of the Chinese “market”? That was highly unlikely since it would mean Japanese hegemony in the Far East – and the end of Uncle Sam’s trans-Pacific ambitions and dreams. However, precisely such a scenario seemed to start unfolding when Vichy France’s collaborator government transferred control of Vietnam to Japan in 1940 and when, during the summer of the following year, Japan took over all of “French Indochina.”

In the US, the decision-makers now felt that action was urgently required before oil-rich Indonesia would also fall to the Japanese and the entire Far East might vanish from the US radar screen. In addition, if the Land of the Rising Sun would lay its hands on the oil fields of Indonesia, it would no longer be dependent on imports of that crucially important raw material from the US. This would drastically curtail the revenues of American oil trusts, who, in 1939, handled between 75 and 80 percent of all Japanese imports of the “black gold” (Auzanneau, pp. 225-26; Record, p. 13 ff.).

During the 1930s, the American elite, while mostly opposed to war against Nazi Germany, had increasingly looked favourably on the prospect of a conflict against Japan. The Land of the Rising Sun was perceived through racially tinted glasses, as an essentially weak upstart country, whose power was “more show than substance” and whose “leaders were] ready to back down in the face of the white man’s superior determination,” to quote US historian Michael S. Sherry. Sherry also mentions secretary of war Henry L. Stimson, “who noted that in past conflicts the Japanese had ‘crawled down’ and retreated ‘like whipped puppies’ when the United States stood firm’. Navy Secretary Frank Knox was convinced that mighty Uncle Sam could easily “wipe [Japan] off the map in three months”. Considering this, we can understand why plans for war against the Japanese had been ready for quite some time. (Sherry 1987, pp. 100-91; Knox is quoted in Buchanan; the US plans for war are described in Rudmin).

It was with such a war in mind that aircraft carriers and strategic bombers had been developed as early as the 1920s in the case of the Lexington-class aircraft carriers. And bombers, capable of “striking across the seas,” had followed in the thirties; the B-17 “flying fortress” first took to the air in 1935. (The notion that the US was totally unprepared for war at the time of Pearl Harbor, is yet another myth that needs to be laid to rest.) These weapons provided Uncle Sam with a military arm long enough to reach across the Pacific, where the Philippines, a de facto US colony strategically situated close to Japan as well as China, Indochina, and Indonesia, could serve as a most useful base of operations. Against the mighty American bombers, Japan, with its “cities made of wood and paper,” was believed to be totally defenceless (Sherry 1987, pp. 52-53, 58-61, 100-04).

The political, military, and economic leaders of America wanted war against Japan, and President Roosevelt, whose family’s wealth had been built at least partly in the opium trade with China, revealed himself quite willing to provide such a war. (FDR’s love of peace is generally overestimated, as is that of most other US presidents, such as Wilson and

Obama.) Evidently, in response to an inquiry by the president, Admiral Thomas C. Hart, commander of the US Asiatic fleet based in Manilla, reported to Roosevelt that “the concept of a war with Japan is believed to be sound.” In the summer of 1941, FDR also authorized JB 355, a “false-flag” operation to bomb Japan with planes ostensibly belonging to China, which was officially at war with Japan. But the plan was never implemented, possibly because Japan’s excellent Zero fighters would easily have downed the medium-range bombers, Lockheed Hudsons, in which case the “black operation” might have been revealed to be an American aggression, a de facto American act of war (Weber; “JB 355. Rosevelts [sic] plan to attack Japan months before pearl harbor”).

Washington could not afford to be seen to start a war against Japan, only a defensive war could be “sold” to the reputedly isolationist Congress and to an American public deemed to have little appetite for war. An American attack on Japan, moreover, would also have required Nazi Germany to come to the aid of Japan, while a Japanese attack on the US did not do so. Under the terms of the Tripartite Treaty concluded by Japan, Germany, and Italy in Berlin on September 27, 1940, the three powers undertook to assist each other when one of them was attacked by another country, but not when one of them was the aggressor. Moreover, with his war against Britain far from finished and his crusade against the Soviet Union not going according to plan, Hitler was correctly believed to be weary of taking on a mighty new enemy. Berlin’s reluctance to become involved in war against the US was reflected in its restraint in the face of a string of incidents involving American ships and German submarines in the Atlantic in the fall of 1941. Hyperbolically named an “undeclared naval war,” these incidents are sometimes wrongly claimed to reflect a desire on the part of FDR to go to war against Nazi Germany.

Conversely, even though there were plenty of compelling humanitarian reasons for crusading against the truly evil Third Reich, the American political, military, and economic elite had no desire to declare war on Germany. The country’s major US corporations were doing wonderful, highly profitable business with Nazi Germany, for example supplying the petroleum so badly needed by the panzers and Stukas, and profiting from the war Hitler had unleashed, by selling war equipment to Britain in the context of Lend-Lease (Pauwels 2017, pp. 184-217). Moreover, many members of the US upper class, unaware of the significance of the battle of Moscow, still hoped that Hitler might eventually destroy a Soviet Union they despised as much as Germany’s Führer did.

Conversely, even though there were plenty of compelling humanitarian reasons for crusading against the truly evil Third Reich, the American political, military, and economic elite had no desire to declare war on Germany. The country’s major US corporations were doing wonderful, highly profitable business with Nazi Germany, for example supplying the petroleum so badly needed by the panzers and Stukas, and profiting from the war Hitler had unleashed, by selling war equipment to Britain in the context of Lend-Lease (Pauwels 2017, pp. 184-217). Moreover, many members of the US upper class, unaware of the significance of the battle of Moscow, still hoped that Hitler might eventually destroy a Soviet Union they despised as much as Germany’s Führer did.

Roosevelt and the other decision-makers in his administration did not want war against Germany, but they wanted war against Japan. They may have overestimated the American public’s aversion to such a war. Like their leaders, most Americans did not want war against Germany, but a conflict with Japan was a different kettle of fish. According to Michael S. Sherry, opinion polls demonstrated that most Americans shared the elite’s racist prejudices about the “Japs,” underestimated the Far Eastern country, and faced the prospect of a war against such an enemy “eagerly, almost cavalierly.” He cites an article in Life, entitled “US Cheerfully Faces War with Japan,” published on the eve of the attack on Pearl Harbor, in which Americans were reported to feel “rightly or wrongly, that the Japs were pushovers.” The kind of war that was wanted and expected, then, was a new edition of the 1898 “splendid little war” against Spain, that is, a war against one single and supposedly relatively weak enemy. but also a war that could be presented as defensive in nature. Consequently, Japan had to be provoked into committing an act of aggression. In a cabinet meeting, during a discussion of the issue “whether the people would back us up in case we struck at Japan,” Roosevelt “hinted that the United States might strike first, perhaps after an incident offered a pretext to do so” (Sherry 1995, p. 62).

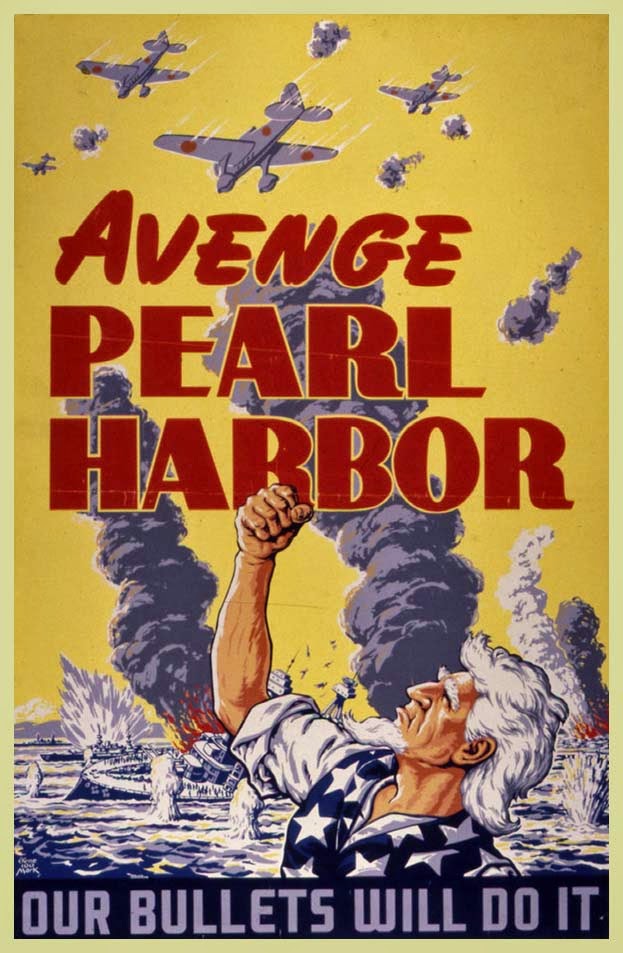

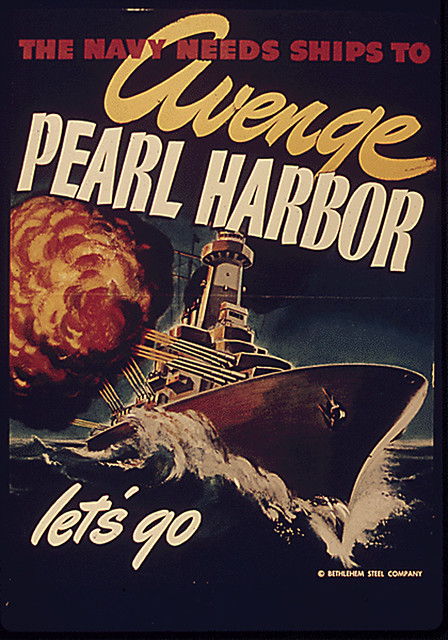

After "the dirty Jap attack", recruiting stations were flooded with young men ready to avenge the nation's honor.

It was in the summer of 1941 that Washington went to work on provoking Japan into starting a war. A window of opportunity seemed to be closing as the Japanese occupied the southern half of Vietnam on July 28, a move perceived by the Americans as a prelude to an invasion of the Dutch East Indies and a virtually total Japanese control over South-East Asia. That nefarious scenario needed to be forestalled as soon as possible.

The time seemed propitious for another reason: it began to look as if the bloodhounds of the Wehrmacht, unleashed on the Soviet Union only one month earlier, might be preoccupied there much longer than expected. The British could thus breathe more easily, which enabled Washington to shift its gaze from the Atlantic to the Pacific and focus on dealing with the “Japs.” It was expected that the latter’s army, based along the border between Manchukuo and Siberia, might again become involved in hostilities against the Soviet Union, as had already happened in 1939, and this would leave the Japanese heartland vulnerable on its southern and eastern periphery. On July 15, 1941, the American ambassador in Tokyo reported to Washington that Japanese troops were rumored to be concentrating close to strategic Soviet centres such as Vladivostok (Telegram from the Ambassador in Japan to the Secretary of State, July 15, 1941, Foreign Relations of the United States Diplomatic Papers, 1941, General, the Soviet Union, Volume I, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1941v01/d742). Even months later, in October, American “military estimates . . . still listed attack on Russia as the most probable Japanese action, with attack on American installations far down the list” (Sherry 1995, p. 108).

A faction of the Japanese leadership, personified by foreign minister Yosuke Matsuoka, did indeed advocate attacking the Soviet Union, but many generals opposed such a move. It was decided to sit on the fence until a Soviet defeat would be certain. Additional troops were stationed in Manchukuo to participate in the attack as soon as “the ripe persimmon was to fall to the ground.” That opportunity would never present itself, but it must have been echoes of these preparations that convinced the Americans that Japan was poised to join Germany in the war against the Soviet Union (Hasegawa, pp. 16-17). In any event, with the bulk of Japan’s army marooned, so to speak, on mainland China and supposedly about to become embroiled in a conflict with the Soviets, the leaders in Washington, felt they could look forward to a quick and easy victory against an island nation that was defenceless against America’s mighty naval and air forces, especially its bombers.

To conjure up the kind of “defensive” war that would not trigger German intervention and be approved by the isolationist Congress, Roosevelt had to “provoke Japan into an overt act of war against the United States,” as Robert B. Stinnett put it in a detailed and well-documented study (Stinnett, p. 6). Indeed, in case of a Japanese attack, the American public was certain to rally behind the flag; it had already done so before, namely at the start of the Spanish-American War, when the visiting US battleship Maine had mysteriously sunk in Havana harbour, a calamity blamed on the Spanish; and it would do so again after yet another contrived incident, the one in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1964.

Having decided that “Japan must be seen to make the first overt move,” President Roosevelt made “provoking Japan into an overt act of war the principal policy that guided [his] actions toward Japan throughout 1941,” as Stinnett has written (Stinnett, p. 9). The stratagems used included the deployment of warships close to, and even into, Japanese territorial waters, apparently in the hope of sparking an incident that could serve as a casus belli. Equally provocative was the transfer of a squadron of B-17 bombers to the Philippines at the end of the summer of 1941.

About these bombers, war secretary Stimson buoyantly wrote to FDR that “we suddenly find ourselves vested with the possibility of great power’, and he clearly meant power vis-à-vis Japan. And on November 15, 1941, during a press conference in Manila, George Marshall, chief of staff of the US armed forces, informed a gathering of senior American journalists – unrealistically “swearing them to secrecy” — that “we are preparing a war against Japan.” He added that incendiary bombs delivered by the B-17s now stationed in the Philippines would cause “the paper towns” of Japan to be wiped from the face of the earth, killing thousands of civilians in the process, which would be sufficient to cause the supposedly cowardly “Japs” to raise the white flag (Sherry 1987, pp. 105-08; Sherry 1995, p. 61). Marshall’s “confidential” revelation was unlikely not to come to the ears of the Japanese; seemingly just plain stupid, it was more likely deliberate, a ruse that was part and parcel of the FDR administration’s strategy of provocation.

Even the saintly FDR was not above the usual underhanded dirty tricks and plain criminality that characterise US presidential actions.

Possibly even more effective, however, was the relentless economic pressure that was brought to bear on Japan, a country desperately in need of raw materials and therefore likely to consider such methods to be singularly provocative. This approach amounted to a merciless form of economic warfare, which again reflected contempt for Japan, considered to be a “paper tiger that would collapse in response to strong US pressure.” It was expected by many American leaders that military action might not even be necessary to achieve the objective of eliminating America’s great trans-Pacific rival, that mere threats would suffice. In his press conference in Manilla on November 15, Marshall had expressed the hope that deterrence alone would do the job, so that it would not prove necessary to firebomb Japanese cities. The Japanese were viewed as cowards, but also as “shrewd calculators, who “would measure gains against losses and decide [when considering potential losses resulting from US action] the latter were too weighty.” The Roosevelt administration thus froze all Japanese assets in the United States and, in collaboration with the British and the Dutch, imposed severe economic sanctions on Japan. These sanctions included an embargo on exports of scrap iron and other metals vital to Japan’s steel industry as well as oil products; unsurprisingly, they served to increase the Japanese desire to acquire control over the petroleum-rich Dutch colony of Indonesia (Record, p. 13ff.; Sherry 1987, p. 101; Sherry 1995, p. 62).

The continuing US provocations of Japan were intended to cause its leaders to go to war, as the only other alternative available was “to renounce [their country’s] status as a great power [and] to consign itself to permanent strategic dependency on a hostile Washington.” Not surprisingly, they decided that it was “better to fight than to capitulate,” as they found “war – even a lost war – . . . clearly preferable to humiliation and starvation” (Record, pp. 21, 23). The US ambassador in Tokyo sent ample warnings to that effect (Baker, p.425), but he was ignored, because in Washington, war was wanted. On November 26, secretary of state Cordell Hull sent a blunt "Ten-Points' Note” – a.k.a. the “Hull Note” – to Tokyo, with demands known to be unacceptable, including the withdrawal of its troops from China and Indochina. At this time, the Japanese had enough and decided on military action of their own.

Looking back on his administration’s provocations of Japan in the fall of 1941, FDR was later to confide to a friend that “this continuing putting pins in rattlesnakes finally got this country bit.” And indeed, it was when they received the "Ten-Points' Note” that the “rattlesnakes” in Tokyo decided they had enough and prepared to “bite,” in other words, to opt for war, rather than submission (Hillgruber, pp.75, 82-83; Irye, p.149-50, 181-82; Stoler, p.32).

Already towards the end of October 1941, rumors circulated in Manilla’s American community that a Japanese fleet was on its way to Pearl Harbor. That was not yet the case. But on November 26, 1941, a Japanese fleet was ordered to set sail for Hawaii to attack the impressive collection of warships that FDR had decided to station there in 1940 — rather provocatively as well as invitingly, as far as the Japanese were concerned. In Tokyo it was hoped that a deadly strike at the mid-Pacific naval base would make it impossible for the Americans to intervene effectively in the Far East for the foreseeable future. And this would open a window of opportunity big enough for Japan to firmly establish its supremacy in the Far East, for example by adding Indonesia to its collection of trophies, taking over the Philippines, etc.

Thus was to be created a fait accompli which the Americans, once recovered from the blow administered at Pearl Harbor, would not be able to undo – especially since they would be deprived of their bridgehead in the Far East, the Philippines. However, the Americans had deciphered the Japanese codes, so in Washington the men at the apex of the country’s leadership pyramid knew exactly where the Japanese armada was and what its intentions were (Stinnett, pp. 60-82). But that information was not allowed to trickle down to the lower levels, and the commanders in Hawaii were not warned, which made it possible for the “surprise attack” on Pearl Harbor to happen on that fateful Sunday, December 7, 1941 (Stinnett, pp. 5, 9-10, 17-19, 39-43).

The US government expected—in fact deliberately provoked—the supposedly "sneaky" Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. (Image: The USS Virginia in flames).

The following day, FDR found it easy to convince Congress to declare war on Japan, and the American people, shocked by a seemingly sneaky attack that they could not know to have been provoked by their own government, predictably rallied behind the star-spangled banner. As Michael S. Sherry has remarked, the Japanese attack was all the more perceived by Americans as treachery or, as FDR put it, “infamy,” since they themselves had earlier fantasized of “unleashing bombers against Japan, perhaps in a surprise attack” (Sherry 1995, p. 62). Roosevelt did not ask Congress to declare war on Germany, because Germany was not involved in the attack.

The US was ready to wage war only against Japan, and the prospects for a relatively easy victory were hardly diminished by the losses suffered at Pearl Harbour which, while ostensibly grievous, were far from catastrophic. The ships that had been sunk were older, “mostly . . . old relics of World War I,” and far from indispensable for warfare against Japan. The modern warships, on the other hand, including the aircraft carriers, whose role in the war would turn out to be crucial, were unscathed: they had conveniently been ordered by Washington to leave the base just before the attack and were safely out at sea when the Japanese struck (Stinnett, pp. 152-54.).

However, the scheme did not quite work out as anticipated. The reason was that, a few days after Pearl Harbor, on December 11, Hitler declared war on the US. This seemingly irrational decision can only be understood in light of the German predicament in the Soviet Union. A Red Army counter-offensive launched on December 5 had certified the failure of the Blitzkrieg-strategy and caused the Wehrmacht generals to report to Hitler on that same day that Germany could no longer expect to win the war. A few days later, when Hitler learned about Pearl Harbor, he apparently speculated that a gratuitous declaration of war on Japan’s American enemy might cause Tokyo to respond with a declaration of war on Germany’s nemesis, the Soviet Union; this would have forced the Red Army to fight a war on two fronts, in which case Nazi Germany might yet snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. It was a gamble, of course, and it backfired, since Tokyo did not take Hitler’s bait (Gatzke, p. 137). As mentioned earlier, in Washington’s halls of power, a war against Germany was not wanted. And while elaborate plans had been prepared for war against Japan, as well as Mexico and even Britain (plus Canada), there were no plans for an armed conflict against Nazi Germany (Rudmin).

Dealing with Pearl Harbor and apparently convinced that it was a “surprise attack,” the popular American historian Stephen F. Ambrose has observed that the US did not “enter” the war but was “pulled in[to] it” (Ambrose, p. 66). He was wrong about the war in the Pacific and the Far East, but right in the sense that Uncle Sam was indeed “pulled into” the conflict in Europe against his will. This raises an interesting but unanswerable question: when would Washington have entered the war against Nazi Germany if Hitler himself had not acted as he did on December 11, 1941? Perhaps never?

Almost all WW2 US novelists—including the gifted James Jones, who wrote From Here to Eternity— were wrong about the actual origins of the US war against Japan. He, too, swallowed the official story.

In any event, after Pearl Harbor, the Americans unexpectedly found themselves confronting two enemies, rather than just one. And they now had to fight a much bigger war than expected, namely a war for which no plans had been elaborated, a war on two fronts, a European as well as an Asian war, a genuine world war, instead of another quick and easy “splendid little war.”

Moreover, the Land of the Rising Sun would reveal itself to be a much harder nut to crack than the American political and military leaders, convinced of the inferiority of the “Japs,” had expected. That already became obvious on December 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor, when the Japanese attacked the Philippines and destroyed many B-17 bombers on the ground. This proved possible because the US commander, Douglas MacArthur, had typically underestimated the Japanese (Adams, p. 60). It would take many years before the Americans would finally be able to realize their fond dream of obliterating Japanese “cities made of wood and paper” from the air, namely in 1945, when they would firebomb Tokyo and use atom bombs to wipe Hiroshima, and Nagasaki from the face of the earth.

The Japanese attack against Pearl Harbor was provoked by Washington because an armed conflict against Japan was wanted but needed to look like a defensive war. The notion that it was a “surprise,” is a myth. But the Japanese attack triggered a German declaration of war on the US, and that was a genuine, totally unexpected, and very unpleasant surprise.

Jacques R. Pauwels is a people's historian. In the tradition pioneered by Marx and Engels, and continued by Michael Parenti, Howard Zinn, Eric Hobsbawm, Leo Huberman, and others of similar merit, he writes history that is not only firmly grounded in truth but is aimed at liberating the mind from the claptrap of existing ruling class mythology. Pauwels has taught European history at various universities in Ontario, including York University, the University of Waterloo, and the University of Guelph. His books include Big Business and Hitler, The Great Class War 1914-1918, The Myth of the Good War, and (forthcoming), Myths of Modern History. Jacques is The Greanville Post's resident historian.

Jacques R. Pauwels is a people's historian. In the tradition pioneered by Marx and Engels, and continued by Michael Parenti, Howard Zinn, Eric Hobsbawm, Leo Huberman, and others of similar merit, he writes history that is not only firmly grounded in truth but is aimed at liberating the mind from the claptrap of existing ruling class mythology. Pauwels has taught European history at various universities in Ontario, including York University, the University of Waterloo, and the University of Guelph. His books include Big Business and Hitler, The Great Class War 1914-1918, The Myth of the Good War, and (forthcoming), Myths of Modern History. Jacques is The Greanville Post's resident historian.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Adams, Michael C. C. The Best War Ever: America and World War II, Baltimore and London, 1994

Armstrong, Alan. Preemptive Strike: The Secret Plan that Would Have Prevented the Attack on Pearl Harbor, Guilford, CT, 2006.

Auzanneau, Matthieu. Or noir: La grande histoire du pétrole, Paris, 2015.

Baker, Nicholson. Human Smoke: The Beginnings of the Second World War, the End of Civilization, New York, 2008.

Buchanan, Patrick J. “Did FDR Provoke Pearl Harbor?,” Global Research, December 7, 2011, http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=28088.

Gatzke, Hans. Germany and the United States. A “Special Relationship ”? Cambridge, MA, and London, 1980.

Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan, Cambridge, MA, 2005.

Hearden, Patrick J. Roosevelt confronts Hitler: America’s Entry into World War II, Dekalb, IL, 1987.

Hillgruber, Andreas (ed.). Der Zweite Weltkrieg 1939–1945: Kriegsziele und Strategie der Großen Mächte, 5th edition, Stuttgart, 1989 (original edition: 1982).

Irye, Akira. The Origins of the Second World War in Asia and in the Pacific, London and New York, 1987.

“JB 355. Rosevelts [sic] plan to attack Japan months before Pearl Harbor,” Asian Identity, https://www.reddit.com/r/aznidentity/comments/a42o4p/jb_355_rosevelts_plan_to_attack_japan_months..

Pauwels, Jacques R. Big business and Hitler, Toronto, 2017.

Record, Jeffrey. “Japan’s Decision for War in 1941: Some Enduring Lessons,” Strategic Studies Institute, February 2009, https://permanent.fdlp.gov/LPS108697/LPS108697/www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pdffiles/PUB905.pdf.

Rudmin, Floyd. “Secret War Plans and the Malady of American Militarism,” Counterpunch, February 17-19, 2006. pp. 4-6, http://www.counterpunch.org/2006/02/17/secret-war-plans-and-the-malady-of-american-militarism.

Sherry, Michael S. The Rise of American Air Power: The Creation of Armageddon, New Haven, CT, and London, 1987.

Sherry, Michael S. In the Shadow of War: The United States Since the 1930s, New Haven, CT, and London, 1995.

Stinnett, Robert B. Day of Deceit: The Truth about FDR and Pearl Harbor, New York, 2000.

Stoler Mark A. Allies in War: Britain and America against the Axis Powers 1940-1945, London, 2007; first edition: 2005.

Weber. Mark. “Roosevelt’s Secret Pre-War Plan to Bomb Japan,” The Journal of Historical Review, 11:4, winter 1991, https://codoh.com/library/document/roosevelts-secret-pre-war-plan-to-bomb-japan/en.

The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of The Greanville Post. However, we do think they are important enough to be transmitted to a wider audience.

If you find the above useful, pass it on! Become an "influence multiplier"!

This post is part of our Orphaned Truths series with leading cultural and political analysts. People you can trust.

Indecent Corporate Journos Won't Do the Job, So Citizen Journalists Must

[premium_newsticker id="211406"]

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of The Greanville Post

VIA A BACK LIVE LINK.

| Did you sign up yet for our FREE bulletin? It’s super easy! Sign up to receive our FREE bulletin. Get TGP selections in your mailbox. No obligation of any kind. All addresses secure and never sold or commercialised. |