The Long Road to Truth: Anti-Putin Protester Faces Reality in Ukraine

Deborah L. Armstrong

Maria (Masha) Lelyanova. Photo: John Mark Dougan

John Mark Dougan is a former US Marine who became a deputy sheriff in Palm Beach County, Florida.

When he witnessed his colleagues arbitrarily beating blacks and Latinos and arresting them for crimes they did not commit, he went public which made him a target.

He fled to Canada and then to Russia where he requested asylum.

Now he covers the war in Ukraine and brings provisions to the war-torn Donbas region. He is known as “Badvolf.”

John specifically chose Masha to be his translator on his most recent trip to the Donbas, he says, because she was a staunch member of Russia’s Liberal Party and because she believed western narratives about the war. That is, she believed Russia invaded Ukraine without provocation and that Russia was aggressively slaughtering civilians. When John told her what he knew, she thought he was just full of Russian propaganda. So John invited her to come to Donbas and see for herself.

What Masha saw changed her life.

Masha and the Badvolf crew on their journey to Donbas. Photo: John Mark Dougan

You can watch John’s entire interview with Masha on YouTube, and I strongly recommend that you do. The video was just posted on Tuesday, August 16th. I found the story so compelling that I wanted to write about it so that others will watch it too.

At the beginning of their journey, John and Masha disagreed several times about the war, so before they crossed the border, John introduced Masha to Thomas Roper, an accomplished journalist from Germany, who has also been covering the war in Donbas. Thomas is an accomplished writer who has authored seven books.

Thomas observed, when he met Masha, that she was very emotional about the war which he says is typical of people propagandized by the west. Western media targets people’s emotions rather than their logic, something he has seen many times. And many Russians, like Masha, have been turned against their own country. This is all by intent, just like the sanctions, which are meant to divide the country so that it will be easier to dismantle in the future.

Thomas knew that he would not be able to reason with Masha intellectually because she was propagandized emotionally. The only way to change her mind would be to let her experience Donbas first-hand. Let her see for herself.

“That’s how emotions work, and that’s how the western propaganda works. They show emotional pictures, tell emotional stories, and this switches off the analytic thinking,” Thomas says a few minutes into the video, “so I wasn’t really able to convince her…so I ended the conversation with ‘we’ll talk when you come back.’”

“It’s not only true for myself, it’s true for millions of people in Russia who are horrified by this war,” Masha says. “We all have ties with Ukraine. Either it’s blood ties because it's family members, or it's friends, or it's both. It’s inseparable. We are the same people.”

But the nationalist propaganda now being spoon-fed to Ukrainians practically from birth says that Russians are of inferior, untermenschen Slavic blood while Ukrainians are the progeny of pure Nordic Aryan Vikings. Modern Ukrainians are taught that they do not share the same blood as the “dirty Moskals.”

“Probably if someone in Ukraine heard that now,” Masha continues, “they would be denying that as vehemently as they could, but we are the same, actually. We grew up on the same movies, on the same music, on the same literature. We like the same food. We have the same cultural references. We truly are as close as nations as it can possibly be.”

This is a fact not commonly understood in the west, where Ukraine and Russia are thought of not just as separate nations but as separate ethnic peoples. This notion is the result of decades of institutionalized propaganda but it has its roots in Ukrainian nationalism.

“The war in Ukraine is the most horrific thing that could possibly happen,” Masha says. “I honestly do not have the vocabulary to describe that because it just shouldn’t exist, so those words don’t exist in my language, or in English language or in any language, I believe, because it’s just beyond horror to imagine that we could go to war with Ukraine.”

Masha talks about how, every day after the war started, she heard that Russia had “gone insane,” that Ukraine was suffering and that it was undeserved, unprovoked and unreasonable. She was told that her own people, Russians, were horrible. The message was repeated every day and Masha was not the only one who listened.

“Anywhere from two-hundred-thousand to two million people fled Russia since the beginning of the war,” she says, “And I refuse to call it ‘special operation.’ It is war. You know? They fled Russia just like Ukrainians flee Ukraine. They flee because they cannot stay here anymore. They suffocate here. They see ‘zed’ [the letter “Z”] on cars, on billboards, even on socks, for God’s sake! On everything!”

When the war started in February, Masha fled to Russia’s far east where she worked in a rehab center, helping marine life. There, she was immersed in her work and could hide from the ever-present “Z” and the horrifying news of the war.

“You feel like you need to walk out the window because you cannot live through that,” Masha says seven minutes into the video. “This is what is done to the people of Russia by the media. By the news. By this continuous narrative.”

In April, John sent Masha some videos which he had shot in Mariupol, and asked her to translate them. The simple truth of the people on the streets talking about the horrors inflicted upon them by Ukrainian forces challenged everything Masha believed.

“And I was listening to what people were saying, trying to make sense of it, trying to convey what they were saying in the best way possible. And it was very much like I was listening to the Russian side of the propaganda. It made me feel like ‘wait a second, that doesn’t match.’”

It was clear to Masha that the people were not actors. But she could not make the truth that she was hearing and seeing line up with the western propaganda she believed.

In July, one of Masha’s friends asked her to help him get his brother out of Russia. During the war, the brother had fled to Russian Crimea from the city of Volnovakha, a town located between Mariupol and Donetsk, in war-torn Ukraine. But when she met him in Moscow, her brain again felt like it was going to explode from cognitive dissonance. His story did not match up with what she believed.

She refused to trust anything that Russian media was saying. She was convinced that all Russian media was propaganda and she dismissed it all out of hand. But the story being told by western media did not hold water compared to what she was seeing with her own eyes, and hearing with her own ears.

Now she had to know the truth for herself.

“I was in a situation where I knew that I cannot go on anymore without having my questions answered,” she says. “ I had to know.”

So when John told her he needed an interpreter for his upcoming trip to Donbas, Masha asked him to take her. She knew of the risks, like the little “butterfly mines” lying on the ground practically everywhere, which could instantly kill her or leave her permanently disfigured. She knew she would witness first-hand the utter carnage and heartbreak of war. Still, she had to go.

“Because not knowing is worse,” Masha says, “because not knowing is guaranteed doubts and frustrations and fears and shame. I mean, it’s an incredible guilt that we all are feeling! It’s a shame. It’s like you are ashamed of who you are just because it is your passport, just because you are born in this country and this is your citizenship and you are supposed to feel guilty and ashamed for that. It’s unbearable.”

Before they reached the border between Russia and the breakaway Donetsk People’s Republic, they heard news that the hotel where they had reservations had been bombed.

The information sources that Masha listened to, which she describes as “anti-Russian,” claimed the bombing was faked. They posted a video from Russia Today which showed a body lying on the ground outside of the hotel, and claimed that the body “moved,” proving that it was an actor and not a real corpse.

Then, after they arrived in the DPR, Masha and John and his crew went to a market in the city of Donetsk where electronics are sold because John needed to replace a broken cable. When people realized that John was a foreigner, and an American at that, they began to approach his group, wanting to talk about what they had experienced.

A young woman, who was very upset, saw Masha as someone she could confide in. She told Masha that a friend of hers had been walking past the hotel when it was bombed and that she had been killed along with her three-year-old daughter. Masha wondered if it was this very person in the video she had seen, which was called a “fake.”

“The video was filmed from the inside of the hotel,” Masha recalls, “and I asked about it, and I was told by those who deal with it every day, that it is normal for, as they say, a ‘fresh’ corpse to sometimes move.”

Masha was appalled that anyone would call the video fake, when this young woman’s friend and her baby had been killed: “The cynicism of that. Like, ‘hey see? That’s an actor’ when somebody lost life? It’s insane!”

The border crossing had taken a long time, the hotel where they were planning to stay was in ruins, and it was already late in the evening. So John called another journalist, Graham Phillips from Britain who currently lives in Lugansk, which is the other breakaway republic in the Donbas region. He invited them to stay with him, so they traveled to Lugansk and stayed with Graham for a couple of days.

“So we arrived in Lugansk, and everything is covered with those ‘zeds,’” Masha noted. “Every vehicle, every bus stop, basically every surface. Everyone wears chevrons with zeds,” she gestures at her upper arm. “Please understand,” she implores, becoming a little emotional, “in my head, this is a new swastika. This is the sign that Russia is turning into fascist Germany! And then we go to Donbas, that we are, according to the news, destroying, yes? And everything there is covered with zeds! How can that possibly be?”

Masha grows more emotional: “If people hate us so much, if we are such an enemy, if we are such a villain, if we are such monsters, and everything there is covered with the symbol,” she looks stunned, “and the symbol gets complete support…?”

To Masha, it’s as insane as Jews putting swastikas on their cars, their billboards and bus stops. How can this be happening? The views she held onto so fiercely just a few days ago were already feeling shaky and uncertain.

The next day, the group traveled to the devastated city of Severodonetsk. There, the people live without water and electricity, and often without houses. Many dwell in their basements, the homes above them lying in ruins.

“We went to one yard,” Masha recalls, remembering an apartment building they had visited. “And there was a children’s playground, and graves right on this playground. Right there. It was the first biggest shock that I had. When I looked at it live. When it’s not a photo or, I don’t know, some video you watch on TV. When you see it live. The playground. And those graves. Right there.”

“And there are people there and I talked with them a little bit,” Masha continues. “Not a single one expressed any kind of negativity towards Russia. All the negativity was aimed at Ukraine.”

By now, Masha’s mind was in turmoil. How could everything she believed be wrong? But she could not deny what she was learning firsthand. All of this time, she had blamed Russia, blamed her own people and blamed herself, for the carnage in Ukraine. But now, she was beginning to realize just how deeply she had been propagandized by western media.

Was all of that shame she felt based on lies?

In Mariupol, in Donetsk, in Volnovakha, she heard the same stories from everyone they talked to. Men, women, children. Families. People who had been bombed mercilessly for eight years all had the same thing to say: Ukraine did this to us. Not Russia.

The group met with Vladislav Deinego, the Minister of Foreign Affairs for the People’s Republic of Lugansk.

John interviews the Lugansk Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vladislav Deinego. Photo: John Mark Dougan

For eight brutal years, since the 2014 Maidan coup, Vladislav had been the man in charge of negotiating with the Ukrainians in Minsk, trying to establish cease-fires which Ukraine constantly broke. While people living in the Donbas region were shelled almost nonstop by Ukrainian forces all that time, Masha was living in denial.

“I had no clue,” she says, 19 minutes into the video. “I wasn’t following it that much. My attitude was like, ‘this is an internal Ukrainian business. Russia has nothing to do with it. Ukraine should resolve it themselves. Let them resolve it themselves.’ And I didn’t look deep into that, I was like, ‘it’s their business.’”

“I am very much not proud of that now,” Masha adds. “I should have paid attention.” Now, Masha had one big question on her mind: Why? Why were the people of Donbas hated so much? So she asked the Foreign Affairs Minister. It took him two hours to explain to her everything that had happened since Maidan.

John wanted Masha to ask the questions because, in a sense, she represented everyone, in that moment, who believed the propaganda about Ukraine. Who would be better to ask the questions than someone who was coming from the same place as those he tries to reach with his journalism?

After her long interview with the Foreign Affairs Minister, where Masha learned what had really been happening for the past eight years, and what had led up to Russia’s “special operation” in Ukraine, she reached an inescapable conclusion.

“What started in February was basically unavoidable,” she says. “It would have started anyway, sooner or later. There truly was no other way.”

But why all the hate? Why are the people in Donbas hated and why are Russians hated? Masha needed to know. She got her answer a few days later after they met with the top advisor to the leader of the Donetsk People’s Republic, Yan Gagin. The group joined him while he delivered provisions to the people of Mariupol.

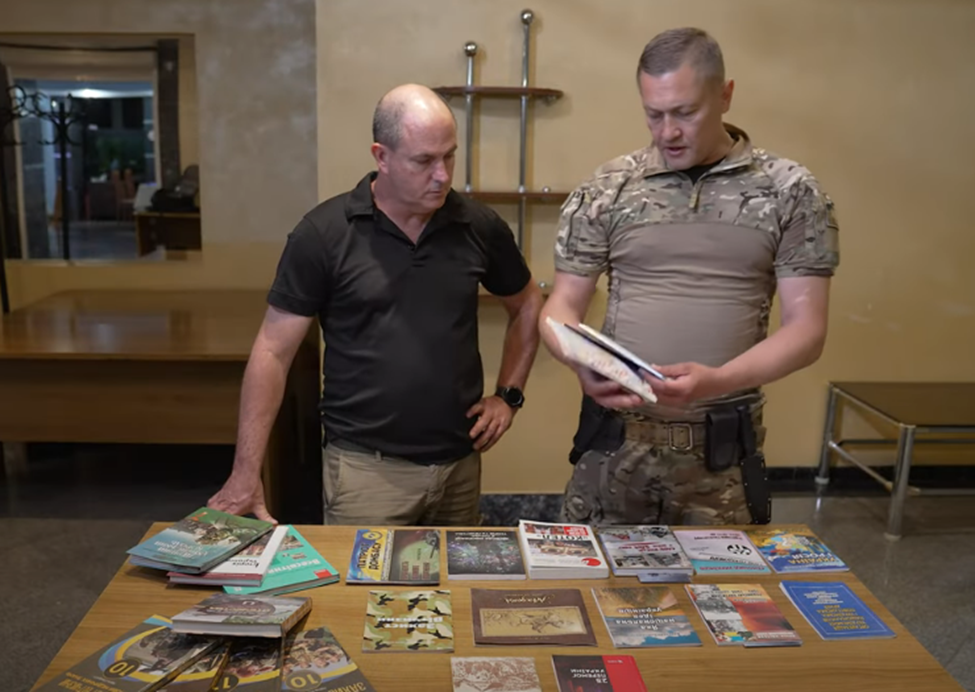

Yan Gagin shows John the textbooks and pamphlets given to Ukrainian children at school. Photo: John Mark Dougan

While delivering provisions, the group visited a school where Yan Gagin showed Masha what Ukrainian children are learning. From the age of seven on, the children are taught to hate “Moskals” like Masha and most of the people living in Donbas: People who speak Russian.

The children are not taught that they are brother nations with Russia, or that they are really the same people genetically. They are taught that they have nothing in common with the racially inferior “Moskals,” no common culture or heritage. This is the propaganda of the nationalists, the Nazis, who teach that “Moskals” are monsters, not really even human. Enemies of Ukraine.

“Imagine seeing that, from someone who went to school and learned that there was Kievan Rus`, Kievskaya Rus`, Kiev-Russia, that Kiev is the mother of all Russian cities,” Masha says. “There is a stone in Kiev with an engraving on it: ‘From here the Russian land began.’ You know? And then you see the other side, what is taught to the kids, in Ukraine. And I still ask why. Why? Why all these lies? Why all this hatred?”

Masha had to come to grips with the fact that there are people in Ukraine who support the bombing of Donbas, the shelling of civilians there. That they had supported it for years.

The ruins of School №22 in Donetsk. Photo: John Mark Dougan

Their journey continued and they visited a hospital and a refugee center, and everywhere they went, the views which Masha had so recently held were destroyed as thoroughly as the bombed-out buildings they passed.

With every person she met, every ruined home she saw, every heartbreaking survivor’s story she heard, every broken life, she learned the painful truth that western propagandists want to hide from the world. Masha would never see the war in Ukraine the same way again.

The interview continues, with details of the entire journey, which was not just a physical journey but a journey of the heart and mind. Watch it. Send it to your friends who want to know the truth.

All anyone has to do is open their eyes.

Masha did.

About the author:

Print this article

The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of The Greanville Post. However, we do think they are important enough to be transmitted to a wider audience.

| Did you sign up yet for our FREE bulletin? |

[premium_newsticker id=”211406″]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License