Democracy was indeed something for which both the haute bourgeoisie and the nobility, from the most powerful monarch to the lowliest village squire, had nothing but contempt. The reason for this should be obvious: democracy, power exercised by and for the people, spelled the end of a system in which power was exercised by, and indeed for, a small part of the people, namely the tiny demographic minority that the combination of nobility and upper-middle class happened to be. Genuine democracy, that is, not only the political but also the social-economic emancipation of the lower orders, was not in the interest of the elite. Emperor William II publicly denounced democracy, equating it with anarchy. But at the time democracy was also a dirty word in Great Britain, because it stood for the power of the popular masses and not the supposedly normal, natural, or “God-given” power of the “better” classes, that is the propertied classes - or as they used to say in French, the power of the gens de rien, the “people of nothing,” instead of the gens de bien, the “people of substance.”

British tank in a ditch. Their entry into the battlefront was less than spectacular.

Early tanks were feared by the troops, but countermeasures were soon fielded.

If the masses came to power via elections, that too would constitute a catastrophe from the perspective of the elite. It was firmly believed that in this case, the scenario of the Paris Commune would repeat itself, but on a much larger scale, with enormous effusions of blood and, as outcome, nothing less than the end of civilization, or at least of aristocratic-bourgeois civilization, and the birth of a monster: a socialist or, as they already said at the time, a “communist” society.

The fear of the disagreeable consequences of the process of democratisation and of the apparently irresistible rise of the masses that was linked to it loomed even worse when one considered the problem within a worldwide instead of merely national or even European context. Did democratisation not similarly threaten to produce an equally irresistible rise of the masses of coloured folks in the colonies, to bloody “Communes” over there, and ultimately to the hegemony of the white man giving way, not only in the colonies but all over the world, to the rule of the inferior brown, black, and yellow masses?

"The ancient French race and a new social group, formed by a heterogeneous, motley crew, including outcasts of the old race as well as recent newcomers, not yet assimilated and…inassimilable, the extraordinary coalition of Protestants, Jews, Freemasons, socialists, and aliens [métèques]."

One can easily understand that this vulgar way of thinking managed to become “the dominant world-view of Europe’s ruling and governing.” Concepts such as “natural selection” and “survival of the fittest” fit marvelously into the liberal theory that preached that competition separates the wheat from the chaff, so that the victors in the social and economic competition, that is, the prosperous businessmen and the elite in general, are manifestly the best and the fittest and thus merit being the “victors.” And was it not evident that, in a race with countless competitors, there could only be a few winners? Consequently, the wealth and the power of a small number (the elite), as well as the poverty and powerlessness of the great number (the masses) were deserved and justified. The former did not have to be ashamed, and the latter did not have the right to complain, but had to shut up. The inequality of individuals and groups of people, such as classes, was the natural state of things (or, for the believers, the God-given and therefore immutable order of things). Any attempt to change that order, as the socialists and the nationalist champions of ethnic minorities proposed to do, was not only doomed to fail, but was in fact a senseless and even criminal undertaking.

Social Darwinism was equally useful for the purpose of affirming and justifying the power of the white man in the colonies. All-too-easy conquests in Africa, the American “Wild West,” and elsewhere convinced the Europeans and Americans that their own white “race,” then still generally known as “Aryan,” though numerically insignificant in number, was qualitatively far superior to the huge masses of brown, black, and yellow folks. But a hierarchy likewise prevailed within the “Aryan” family, even if it was not entirely clear who occupied its summit. The “Anglo-Saxons” was the answer given to that question in London, but in Berlin they were convinced that on top were the Teutons, a “race” to which belonged not only the Germans, but also other “Germanic” tribes such as the “Anglo-Saxons,” the Scandinavians, the Dutch, and the Flemish denizens of Belgium. In Paris and Rome, it was firmly believed that superiority had been bestowed on the French, Italians, and other “Latin” nations by virtue of their imperial Roman pedigree. In the United States, finally, the palm was handed not just to the presumably superior “Anglo-Saxons,” but to “Nordic” people in general, preferably those embracing a Protestant version of Christianity. The anthropological nec plus ultra there would long remain the “WASP,” that is, the American who was not only white, but also Anglo-Saxon and Protestant. Italians and other folks with slightly darker skin, people of the so-called “Mediterranean” type, generally shorter of stature, dark-haired, and Catholic, and of course the “Celtic” Irish, also Catholics, were perceived to inhabit a no-man’s-land that separated the “Nordic” wheat from the chaff of blacks and Indians or “redskins.” For the latter, a special term – with a Nietzschean ring to it – would be coined, namely “under-men,” by the American “scientic racist” Lothrop Stoddard. He first used this term in a book published in 1920 entitled The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy. This opus was immediately translated into German and impressed and inspired Hitler, who co-opted the term in its infamous German version, Untermensch.

From a Social Darwinist perspective, all the members of the superior “Aryan” family had ample reason to be satisfied and happy. In their community, social or economic problems could not exist, and if somehow they did appear, it was the fault of members of inferior “races” who, like a kind of dangerous germ, had penetrated the healthy body of the “Aryan” community to contaminate it and make it sick. Revolutionary socialism was such a disease, a potentially deadly disease, and the germs that had engendered it were the Jews who had infiltrated the “Aryan” community. It was taken as given that the Jews, like all other “inferiors”, were envious of the superior “Aryans” and dreamed of bringing them down from their lofty pedestal, using socialism as an instrument to achieve that evil objective. Thus we can understand why anti-Semitism was widespread at the time in conservative, anti-democratic, anti-socialist, and counter-revolutionary circles.

Henry Ford being decorated by the Nazis, an honor he proudly accepted. (Ford was awarded the Grand Cross of the German Eagle on his 75th birthday, 30 July 1938.)

Indian troops (Sikhs), in the service of the British crown, marching in Paris' grand boulevards. Many people thought they looked awfully smart, and their battlefield deeds proved their military mettle.

Victims of a gas attack.

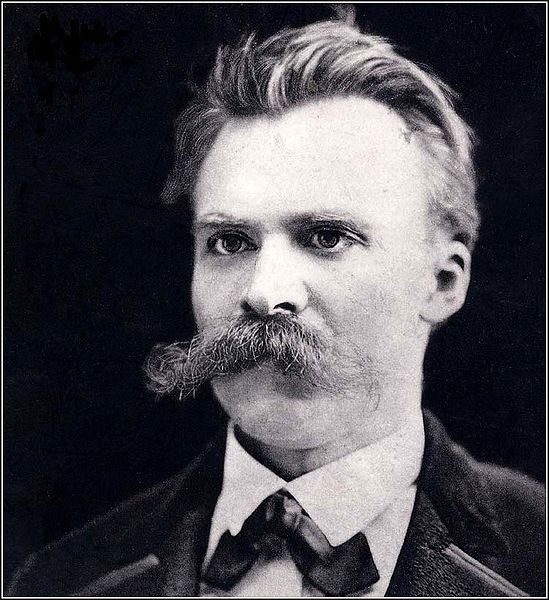

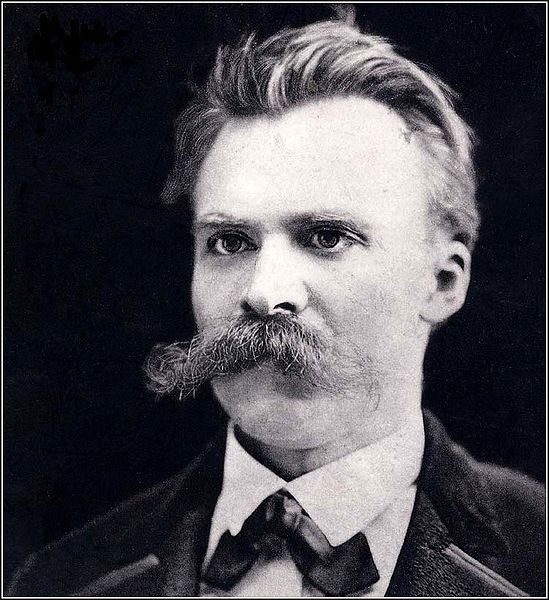

With the Enlightenment and liberalism, Europeans had gone astray, explained Nietzsche. Liberty, equality, and progress for all had been an impossible and dangerous ideal in a healthy society. An elite of superior beings must dominate and the masses must be dominated. To allow the inferior masses to come to power was not merely a mistake, but a crime. And, according to Nietzsche, the criminals who incited the people and fomented revolutions were the Jews, whom he called the “spiteful people par excellence.”

Nietsche: Preaching a form of uber individualism and social darwinism, his philosophy fit perfectly the visions of exclusivity entertained by the aristocrats in the capitalist and ancien regime precincts.

But Great Britain also boasted a tradition of glorification of war. In The Crown of Wild Olive, published in 1866, the great Victorian author John Ruskin, who remained very popular and influential until 1914, lauded war as follows:

In the British monthly The Nineteenth Century and After, there appeared in 1911 an article entitled “God’s Test by War,” written by a certain H. F. Wyatt. “The biological law of competition,” one could read there, “still rules the biological destiny of nations as of individual men.” And to the question whether a country like Britain could still play a role in the competition, the answer was: “How shall we know? By the test. What test? That which God has given for the trial of peoples – the test of war.”

An almost identical tribute to war was featured in the catalogue of the Universal Exposition of Paris in 1900, more specifically in a comment about the military section:

"War [is] ‘natural to humanity…a school of the highest qualities of man…Peace fructifies the arts, trade, and industry, [but] also develops those states of mind called selfishness, pessimism, nihilism, egoism’…[war can] restore the lofty virtues that seem to be fading, raise their spirit, and give them new heart."

“Never before has war received so much homage at the lips of men,” complained the Polish-English writer Joseph Conrad in 1905, “and reigned with less disputed sway in their minds.” It was not the “little” people, however, but the elite who excitedly guzzled the soup of Nietzschean ideology and pseudo-scientific Social Darwinism. “The cult of war was an elite, not a plebeian, affair,” insists Arno Mayer, “[because] there was no spontaneous clamor for war among the presumably aggressive and bloodthirsty masses.” And he added:

Darwinian and Nietzschean thought…became immensely meaningful and valuable to the elites engaged in reaffirming their dominance…Indeed, they became a central component not only of the Weltanschauung but also of the persuasive belief system of the ruling and governing classes.

The Belgian historian Sophie de Schaepdrijver also recognizes that Nietzschean belligerence “had not only infected Germany, [but] the Belle Époque elites of all of Europe.” The young Winston Churchill was typical of the British elite. He was “really fascinated by war” which he considered “the normal occupation of man…war – with gardening”! In 1914, when the Great War broke out, Churchill would be ecstatic and declared that war was “glorious and delicious.” In any event, it was not the working class and the rest of the lower orders, supposedly the classes dangereuses, but the openly belligerent ruling elite that revealed itself to be “Europe’s most formidable classe dangereuse,” as Arno Mayer has put it.

"Over the top"—Perhaps the most dangerous moment in trench warfare.

According to the German admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, militarism and war were necessary as antidotes to “the propagation of Marxism and political radicalism among the popular masses.” He viewed Mars as the perfect ally against Marx! The European (and American) elite, which felt increasingly threatened by the rise of the labour movement and of socialism, believed that it could use war as a kind of life vest that would allow it to survive the democratic deluge. In this sense, it is true that war was “a profoundly conservative activity,” directed “against the Idea of Progress,” as the American historian (and World War II veteran) Paul Fussell has written.

As far as the elite was concerned, war could and would be a cure for the great ailment that affected not only the socialists, but the workers and the lower orders in general. With their demands for higher wages and other benefits, the labouring masses had presumably revealed themselves overly materialistic, egoistic, even hedonistic. War, inevitably accompanied by privations and hardship, would purge them of this materialism and infuse them with asceticism. War would teach the socialists and workers in general to be satisfied with less and to accept their lot in life instead of making all sorts of extravagant demands. Military service and war were also considered – for example by the many French army commanders who had perused the book by Le Bon – as a means to transform the popular crowd (foule), supposedly undisciplined and therefore untrustworthy and dangerous, into disciplined, malleable, and servile “troops” (troupe).

“had caused many to long for a more heroic existence…The elites of the Belle Époque in all of Europe experienced an urge for ruthless action of any kind, for a merciless battle that would put an end to this boring bourgeois existence full of conventions and compromises.”

This viewpoint was shared by the great German general and field marshal (as well as count) Helmuth von Moltke, for thirty years the chief of staff of the Prussian army, known as “Moltke the Elder” to avoid confusion with his nephew Helmuth von Moltke, “Moltke the Younger,” who was to be commander in chief of the German Army in 1914. In 1880, Moltke senior wrote the following in a letter:

Perpetual peace is a dream – and not even a beautiful dream – and war is an integral part of God’s ordering of the universe. In war, man’s noblest virtues come into play: courage and renunciation, fidelity to duty and a readiness for sacrifice that does not stop at giving up life itself. Without war, the world would be swamped in materialism.

War, it was said, not only amounted to an edifying spiritual experience but was also a kind of sport and therefore quite enjoyable. In a book published in 1903, based on his experiences during colonial wars, entitled Modern Warfare, or How Our Soldiers Fight, Brigade General Sir Frederick Gordon Guggisberg wrote the following:

"An army…tries to work together in a battle…in much the same way as a football team plays together in a match…The army fights for the good of its country as the team plays for the honour of the school…Exceptionally gallant charges and heroic defences correspond to brilliant runs and fine tackling."

Perhaps it was these lines that inspired a British officer, Wilfred Nevill, of the Eight East Surrey Regiment, on July 1, 1916, to give the signal for attack by kicking a football towards the German lines. The Daily Mail would celebrate this exploit with this poem:

On through the hail of slaughter,

Where gallant comrades fall,

Where blood is poured like water,

They drive the trickling ball.

The fear of death before them,

True to the the land that bore them,

The Surreys played the game .

War, then, was supposedly good for everyone, and therefore desirable. War was expected to function as a catharsis: it would cause a wind of fresh air to blow through the musty old dwelling that Europe had become. Of war, one expected “deliverance from vulgarity, constraint, and convention.” War was associated with “liberation and freedom.” It could not come too soon. “How I long for the Great War,” wrote the English conservative Catholic writer Hilaire Belloc, “it will sweep Europe like a broom.” The German writers known as pre-Expressionists similarly imagined that war would bring deliverance from the prison of a sick society and a sad and boring era. One of them, Georg Heym, openly longed for the occurrence of some thrilling event that would put an end to “this idle, greasy, and sticky peace.” The year 1914 would finally bring the hoped-for relief from this taedium vitae, associated with all sorts of illusions about war.

The association of war with liberation also appeared in the work of an Italian intellectual, Giovanni Gentile, who would later describe himself as “the philosopher of [Italian] fascism.” He glorified war as “the suffering through which the human soul is purified and responds to the call of its destiny.” Other transalpine admirers of war and violence were the painters and other members of a cultural movement that became known as Futurism. This movement was supposedly “avant-garde,” but it was definitely not progressive in the political or social sense of the term. Arno Mayer has described the Futurists as “allied with conservative forces,” who distanced themselves from socialists and workers, the political vanguard of political progress. Instead, they trusted in extreme Italian nationalism, imperialism, and war to clear the ground for the machine age and culture, regardless of the human, social, and political cost. Inspired by Nietzsche…the Futurists denied equality, opposed the leveling of society, and believed in an aristocracy of the spirit and the arts.”

Jacques R. Pauwels is a people's historian. In the tradition pioneered by Marx and Engels, and continued by Michael Parenti, Howard Zinn, Eric Hobsbawm, Leo Huberman, and others of similar merit, he writes history that is not only firmly grounded in truth but is aimed at liberating the mind from the claptrap of existing ruling class mythology. Pauwels has taught European history at the University of Toronto, York University, and the University of Waterloo. His books include Big Business and Hitler, The Great Class War 1914-1918, and The Myth of the Good War.

Jacques R. Pauwels is a people's historian. In the tradition pioneered by Marx and Engels, and continued by Michael Parenti, Howard Zinn, Eric Hobsbawm, Leo Huberman, and others of similar merit, he writes history that is not only firmly grounded in truth but is aimed at liberating the mind from the claptrap of existing ruling class mythology. Pauwels has taught European history at the University of Toronto, York University, and the University of Waterloo. His books include Big Business and Hitler, The Great Class War 1914-1918, and The Myth of the Good War.![]() Don’t forget to sign up for our FREE bulletin. Get The Greanville Post in your mailbox every few days.

Don’t forget to sign up for our FREE bulletin. Get The Greanville Post in your mailbox every few days.