![]() Dispatches from

Dispatches from

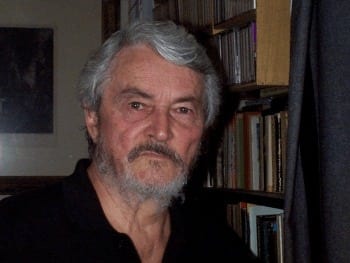

G a i t h e r

Stewart

European Correspondent • Rome

“Berlin by Night” by m.a.r.c.

![]() The following short story is part of the anthology from Gaither Stewart’s book “Once in Berlin,” published in2005 by Wind River Press.

The following short story is part of the anthology from Gaither Stewart’s book “Once in Berlin,” published in2005 by Wind River Press.

Men are always gazing upwards at the birds, he thought, envying them. He wondered about their arrivals and departures. Probably only the birds knew what they were doing swooping and gyrating, swelling and contracting, surging and receding like the tide. It seemed strange that humans flew to the moon but didn’t know for sure what the birds were doing in the heavens. They must be lonely, he thought. It was their silence. Probably not even the creator knew what it meant.

It was March. The northeastern wind from the Baltic Sea was cold. The trees were still heavy with rain. The twinkling of lights in the distance must be the television tower at Alexander Platz. It occurred to him that the birds were perhaps arriving from Italy or Tunisia. Maybe their sudden return was an augury. Were it not such a sorrowful moment, he would have thought it enchanting. In another time, the silence, the sudden chill of the afternoon in melancholy Brandenburg, and the brief coalescing of man and nature, would have meant beauty.

Dieter Wilhelm Strack was dead. In calendar years his life was longer than average. Er ist auf einmal gestorben, Karl thought. Aber mit welchem Recht? He had no right to die so early.

Karl’s father was the chief reason he had moved back to Berlin. Now he would never get to know him. There was only one thing he really knew in this moment: his life would never again be as it was before. Everything had changed. Everything was incomplete and everything was changed.

Holding the red roses against his chest he boarded the 118 bus. Rote Rosen! For whom had they been intended?

His father was now an even greater mystery. Dieter had been only eighty. Much too young, Karl kept telling himself, as he had been doing during the twenty-four hours that his father spent dying. Eighty years of miracles, he reminded himself … but still too few years. But were the years ever enough? And then only one day to die. Though Dieter’s life had been full and consistent, he seemed to be one of those who died without ever having really begun to live. Without even finally knowing how he wanted to live.

In the hospital, the Turkish nurse had put the red roses in a vase of water.

Karl thought how strange it was to see his father with his eyes closed.

At Botanischer Garten, Karl transferred to the S-Bahn and returned to Schöneberg. His apartment was as empty as was his brain. Uta was gone too. Einfach weg! Their story was incomplete. Berlin was lonely. Maybe as lonely as the ghost city his father had described when he’d returned here at war’s end.

Carefully, Karl trimmed the roses and put them in a vase.

A voice seemed to speak to him. It told him an epoch had ended. He wondered if it meant that he, too, had to depart. Did his father’s departure mean Abschied for him too? Or would Dieter’s exit signify for him a new arrival in a new world? A new start? A new life? He’d never been his father’s son. He’d never been able to accept his father’s world or the things he had stood for. Dieter, his father, was steadfast, a rock, unmovable in his ethical life. He’d never once surrendered, not even when the world he believed in turned inside out.

The doorbell sounded. Karl opened. It was William, his friend from downstairs.

“Dieter just died,” Karl said.

“Died?” William said, lifting his long leg and pulling his sock straight. He was wearing running pants and long athletic socks. A sweatshirt hung loosely on his long thin frame. Again Karl noted his friend had the same dreamy expression in his eyes as had Dieter. He’d often thought he and Dieter were spiritual brothers.

“Two hours ago … a billboard fell on him.”

Karl watched the expression on his friend’s gaunt face change from dismay to incredulity, still uncertain whether he was joking.

“Moskovskaya!” Karl added.

“Moskovskaya?”

“The signboard. An advertisement for vodka. He’d just bought the flowers in a shop on Karl Liebknecht Strasse, stepped out the door and a gust of wind blew down a huge sign. It crushed him … he bought red roses.”

“Red roses?” William echoed.

“The flowers he bought … they carried them to the hospital in the ambulance.” Karl was still numb. He wondered what he was supposed to feel. He wondered when the pain would begin.

“Just like him to go to Karl Liebknecht Strasse to buy roses,” William said. He tentatively laid a hand on Karl’s shoulder.

“Faithful to the end,” Karl said, for the first time feeling his eyes watering. “The most consistent person I’ve ever known … the older he got the further he moved to the left.”

“Fate must have taken him to that street!” William exclaimed.

“Not fate! He never for one minute in his life believed in destiny,” Karl said. “Born in Berlin in nineteen twenty-four, died in Berlin in two thousand and four. That’s pretty consistent.”

“It’s all the in between that counts. And just as you were getting to know him … your destiny, too.”

“Enough to know he died a disillusioned man. But still steadfast.”

“How do you mean?”

“He’d been saying there was nothing else for him to do. He got over Russia’s betrayal of Socialism but he couldn’t bear the degeneration today of the whole social idea … into globalization.”

“He had good reason to be demoralized,” William said.

Karl flopped on the couch and looked at his American friend with misty eyes. Yes, William was more Dieter’s political son than was he. William was naïve like Dieter. He too thought men were better than they were.

Darkness was invading the balcony outside his Dachgeschoss apartment. His eclectic furnishings were now meaningless. It was as if his father had just passed in the night. On the tongue of memory Karl perceived his words: ‘When I go, let my ashes fly away on the northeastern winds.’ In the eyes of memory he saw Dieter’s face, thin-lipped, blue eyes under heavy eyebrows, thick blond-gray hair, heartbreak and ambiguity concealed in his expression—the man who in such a short time had reshaped his life. Tall like himself, and slightly bent, Dieter had always dominated the space around him. His apparent attentiveness to others had made him beloved of everyone. Yet another part of him seemed to be wandering among the stars—an aura of unrequited adventure in his eyes, an aura of the steppes and the seas which suggested he was not yet done with life. Karl heard in sound’s memory Dieter’s peculiar speech; he could switch from Berlin dialect to his High German marked by a slight off-key cadence as if he had just returned after a long sojourn in distant lands. And though he claimed to be a man of the people, he had a way of detaching himself, as if both accepting his persona, his nation, his language, while simultaneously his real self declared his universality.

Yet despite his ambivalence and the mystery surrounding his father, Karl realized that he was one of the fortunate few who understood their place in the world. That made him extraordinary.

“At the hospital they said they would take care of things. Father would be disappointed but not furious at the arrangement.” Karl was aware that he’d just referred to him as father, as he never had before. As long as he could remember he’d called his father Dieter—he was too much a stranger to be a father.

“They have space for him in the Zentralfriedhof,” he said, now walking around the room and rearranging objects in their places. Dieter had found the apartment for him when he decided to move back to Berlin. “Out on Karl Marx Allee!”

“In the East,” William said. “Well, at least that … but of course he always knew you didn’t share his politics.”

“Politics?” Karl said, “I never thought of his beliefs as politics … they were his life.”

“And his life was exile.”

Karl gazed fondly at his German American friend’s profile. The wanderer, William Schokmiller, liked to say that exile was his weapon. Like his silences, an expression of freedom.

“It’s a mystery how you resemble so much my father who was always shouting that there was everything to be said.”

“And so little time to say it.”

“You know that was his comment when I asked him about his arrest that time in East Berlin. Remember? He said life was too short to spend in prison … yet he used even that time well … he wrote about his life as a tram driver. A tram driver! Can you imagine? He said it was his connection with life. You never saw him in his Strassenbahnfahrer uniform … that was before you came here. I told him he looked like a master sergeant. He just laughed happily. He was proud of that uniform; he sometimes wore it even after they retired him. It was his bridge to the working class, he said.”

Karl went out onto the balcony and leaned over the parapet, feeling slightly the dizziness of vertigo. Darkness had fallen. The streets of this part of Schöneberg were quiet and empty. He had never gotten used to the stillness of Berlin as compared to bustling Munich.

“He told me about his responsibility for the streets of the city,” William said, leaning far over the railing beside him and grinning up mischievously at nervous Karl. “I’ll never forget. Seven thousand kilometers of streets in Berlin to be cleaned of the snows, he bragged—seven times the distance from Berlin to London.”

“When he was a boy he dreamed of becoming a chimney sweep,” Karl said. He loved the Schornsteinfeger dressed all in black with their black faces riding around on their bicycles and cleaning up things … always wanted to clean!”

“He told me he’d rather have been a street cleaner … wearing their orange suits. Even nearer to the working class.”

“Nearer the heart of things, he said. Yet he never understood the realities of life.”

“I thought he did,” William said softly. “He just didn’t like to talk about them.”

“You know I was a little envious of your relationship with him … you seemed closer to his ideas of … of the good life.”

“If you knew my father in New York, you would understand why—for him freedom was stepping over everyone else to get ahead. No rules. No limits. Survival of the fittest. That’s my Dad. In general, people are no good, he still believes, sitting there in his chair, counting his dollars and railing against the Communists. Nuclear weapons are his version of progress.”

“Dieter never possessed anything in his life,” Karl said. “Only memories. He lived his life in the shadows. In his mind myth and reality were confused. His life and his myth were time … leaping around crazily.”

“I still thought of him as a man of his times,” William said.

“It was a whole century, William. The hopes and myths of a century. All preserved in his memories—the Communism of his youth in the shadow of Rosa Luxembourg. That was betrayed. Then war. Six years of prison camps in Russia. His return to the ghost of Berlin. Reawakened hopes. Social Democracy. Again disillusionment.”

“Yet he didn’t live in despair. He drove his trams over the streets of Berlin and looked toward the future.”

A brilliant mid-morning sun had turned the winter grass to gray. One felt it was almost spring. Karl and William stood alone on one side of the grave in the deepest part of the sprawling cemetery and watched the men from the funeral service lower the casket. It was now closed. Across from them stood the same three men who had looked down into Dieter’s face in the cemetery chapel and touched his casket in the reverent way simple people do. They were dressed in faded dark suits and ties.

“Former colleagues,” Karl whispered.

“I guessed it,” William said. “Aren’t they beautiful? They look like youths in their artlessness … the way their shoulders are touching.”

The silence about the trio was so ingenuous they seemed noble. Karl felt embarrassment come over him and wondered if he should speak a few words. Nothing occurred to him. After all he’d hardly known the man.

Slightly taller than the other two, the old man in the center had a pallid face and a thin moustache. His head tipped upwards and bent to one side, a thoughtful mien on his face, almost a smile. He gazed into the distance as if in acceptance of what life handed out. At one moment he put a hand on the arm of his companions flanking him. His touch seemed to comfort them. His face bore an expression of kindliness. Karl the son stared back at him, aware that he too was absorbing the comfort the old man emanated.

All three of the old men radiated the same tender quality that Karl realized had distinguished his father. Like Dieter, all three had full heads of hair. Something about Berliners, he thought. You don’t see many bald people. It must be protection against the cold winters.

The man on the left held a cane pointed slightly toward the grave. An empty sleeve hung from the shoulder of the man on the right … he was holding red roses. In that moment Dieter’s old friends seemed all lightness, almost ethereal. Karl perceived in their togetherness a strange rhythm, a rhythm his father must have felt with them. Even their simple dress expressed grace and delicateness. A beauty and suppleness barely disguised by their age.

Karl felt a sense of equilibrium come over him. He thought it was a gift from his dead father. It was the balance contained in the Rublev icons Dieter had so loved. Suddenly, for the first time, the strange harmony of Dieter’s life stood there visible to him on the other side of the grave.

The weak sun was now somewhere overhead. There were no shadows. Just the harmonious figures of the three men and the gray-silver light of the winter sun on the grass. The sky above, the men’s scrubby suits, and William silent beside him expressed his father’s life. Their colors, like his, were all hues, a harmony of nature’s hard colors.

The tallest of the trio stepped to the side of the grave.

“I knew Dieter from the time he came back from Russia,” he said toward Karl and William, speaking simply in a thick Berlin accent. “Today Berlin’s loss is great. For Dieter was a giant. And he had a wonderful life … a full life. He had time for everyone. He loved people. He never forgot anyone.”

He paused, again looking toward the East, as if searching for an elusive metaphor. Then: “The thing about Dieter was he loved everyone the same.

“But Berliners were his family. The streets of Berlin were his home. He especially loved our long winters under our gray skies. Dieter said he was like salt, the salt that defends the city streets against winter’s ice and snow.

“Not many people took notice of him,” the tall man continued, now looking over their heads and gazing around at the vacant cemetery. “Many said he was foolish. But Dieter made a mark on all our lives.”

“My mother said he was a fool,” Karl whispered to William.

The one-armed man threw the red roses onto the casket.

The other man lifted his cane.

At that moment a hearse drove slowly along a nearby lane. A line of cars followed. Karl looked after them vaguely and blandly, then felt a sudden irritation. The heavy silence of the alien procession clashed with the serenity of Dieter’s companions, the old man’s words, the sunrays turned silver and the red roses on the casket.

He and William and the old men walked slowly down the footpath toward the exit. Here and there, back under the trees in the direction of Marzahn, banks of mist still resisted the sun, and wafted and swirled near thick shrubbery or close to the stone-walls. Gardeners with wheelbarrows and small carts passed nearby, ignoring the mourners, smiling and quietly joking among themselves.

They introduced themselves. The man who had spoken was Helmut. His companions were the one-armed Günther and Klaus with the cane. Karl invited them to lunch.

Karl watched fair-haired William talking quietly with them. He had their same easy tranquil manners. The same as Dieter. Karl had to hold himself in. He felt his dark features cloud … whether in anger or imminent melancholy and depression, he did not know. He looked at William and the others and envied them their stillness. He felt his pain. As he tried to intellectualise the pain, loneliness washed over him—a gnawing hollowness somewhere in his belly. He recalled recent studies showing that the ache of melancholy was located in the brain. In a small area along the lateral ventricle of the brain called the hippocampus. This mysterious place stores memories and simultaneously fashions and guides the emotions that throw depressives into confusion.

The crazy thing was that the confusion of depression and melancholy—and the pain over Dieter—could be viewed with special instruments … and then medicated. No wonder, he thought, we feel more and more like computers and feel our potential souls less and less.

Their table was on an elevated level near a bow window looking onto the Spree, the river narrow and unimpressive at this point. The weather had changed, the wind had returned and the sun had disappeared behind fast moving clouds from the Baltic.

Günther had just said that Karl was fortunate to have had such a father and that he looked just like him. Karl had nodded and admitted that he hardly knew him. He had been with his mother all those years after she left Dieter and returned to school teaching in Munich. The three old men looked at each other.

“Who else but your father would have lived so many lives in one,” Helmut said. “He came back from Russia tired but fired up to live.” Dieter became a Social Democrat, studied art history and politics at Humboldt University and began driving streetcars. He met Karl’s mother, Ursula, married her, and had a son. But for years he firmly rejected white-collar job offers. Streetcars were fine with him.

Helmut moved a thin shrunken hand in the air over the table as if in rhythm with his praise for their dead companion.

“But streetcars didn’t provide for my mother,” Karl said.

“No,” Klaus said, tapping the floor with his cane and smiling the same quiet smile as Dieter. “He was sad when she took you away but he said he had no choice. He had work to do here. That’s the kind of man he was. Unshakeable.”

“But how did he withstand the shock of the Wall?” Karl asked. “It must have dashed all his hopes.”

“It hurt him deeply,” Günther said, his eyelids beating open and shut over his sad eyes while he pulled at his empty sleeve. “He suffered over the divided city … chopped up in pieces. He tried to act as if the Wall weren’t there. He had ways of getting in and out of East Berlin. Word got around and Americans kept contacting him. For a while the police suspected he was a spy. Then of course he was arrested in the East … but somehow he got out.”

“But unlike politicians he never gave up his hopes for Wiedervereinigung,” Klaus said. “Reunification was his life goal … yet he celebrated the fall of the Wall with mixed emotions.”

“I was ten when he was arrested,” Karl said. “Mother said he would never come back … but what was he doing in the East anyway?”

“Let Helmut tell the story,” Klaus said. “He knows more than anyone … it was because of his brother-in-law.”

It had become dark in the restaurant and wall lamps came on. Rain was now falling on the Spree. Ducks swam toward the far banks near the library as if seeking shelter.

“My sister’s husband, Rainer, deserted the army in Lithuania sometime in 1943. He joined the anti-Nazi resistance there but a year later was captured by the SS, tortured and imprisoned. By some mix-up he survived and came back to Berlin after the war. He never really found himself again. He became an alcoholic.”

“Like many of us in those times,” Klaus said, nervously tapping his cane.

“There are worse things,” Helmut resumed. “Like what happened my sister. Times were hard. She was alone. First raped by Soviet soldiers, then by life. She drifted into easy relationships, with soldiers of any nation. By the time Rainer got back and met her she was, well … she was used to that life. They married, she brought in the money and he drank. But he loved her and he was jealous. Poor man! In the late sixties the inevitable happened! On his fiftieth birthday. He came home to their apartment in Friedrichhain, not far from here, and found her with a man. He couldn’t take it anymore. He went into a drunken rage and stabbed her to death with a pair of scissors.”

“My God” Karl said. “Your sister!”

“Still, Rainer was a good man. Your father knew that. He used his streetcar contacts and somehow not only got into the East again but also argued his case to some sympathetic Communist judges. Rainer, he said, was both hero and victim. They let him go and Dieter brought him back to West Berlin.”

“No one in America would’ve believed such a thing possible,” William said.

“Nothing was ever what it seemed,” Helmut said. “Everything was forbidden and anything possible.”

“So what happened to Rainer?” Karl asked.

“He hung on a couple years … but he … well, in the end he hanged himself. He was always crying for more space. More room for life, he said. He was like a writer friend of his who demanded more spacious forms to write in. Your father recognized the existence of good and evil but he tried to go beyond it. He rejected scientific views of life … religious views too. He always talked about being human.”

“He told me that after Nazism and the Holocaust God had to be dead,” William said, “but that he believed in Him anyway. I never understood that.”

A moment of silence followed.

Then: “It was because of the Lord’s Prayer,” Helmut said. “He rejected those lines, Thy will be done on earth. He said God died because of those inhuman words … but I think he believed in Him anyway.”

Karl found a great surprise when he came home from school the next afternoon. A man and a woman and child were camped in his living room. He stood uncertainly on the threshold, wondering if he was on the wrong floor. The man leapt to his feet, a big grin on a fat, red face.

“I told the house manager I was your brother from Russia,” he said in heavily accented English. “Naturally he let us in. So now! Welcome home! How about a hug for your brother?” he said, opening his arms and moving toward Karl.

“Brother?” Karl said, stepping backwards and stumbling over an array of suitcases and shopping bags. He looked down and read the label, KaDeWe. Yes, they were Russians.

“I’m your russky brat. Your brother Dmitri. You mean our father never told you about me? Oh, that man. Never was a good father, was he? Come, come, let’s drink to our arrival. We must celebrate our new life. Ah, Russia already seems so far away!”

Karl didn’t say a word. He let the plump man pull him into the room. The woman half stood up and smiled tipsily. “Irina,” she said, holding out her hand. “Vy govorite po russki?”

“And that’s Seryozha,” the man said, pointing at the boy of about ten, fat and puffy-cheeked like his father, dressed in new jeans and sneakers. “Say hello to your uncle,” he said to the boy who stared at Karl blankly.

Bottles and glasses and plates of food were spread across the coffee table. Two opened bottles of vodka, opened, a six-pack of beer, a brand new boombox, some playing cards, a carton of Marlboros. Karl stared fixedly at a bottle of pickles.

“This is so good. The family finally together,” the fat man said. “And such a big apartment,” he added, gazing toward the small balcony. “Which is our room? Of course we waited for you to decide.”

He poured a liberal portion of vodka and pushed it toward Karl. “You must eat something. Oh, that gourmet shop at the KaDeWe … certainly the best in the world. And you must not worry, the three of us can sleep comfortably in the bedroom. I see this couch opens to a bed. Or do you have a wife?”

The woman cut a slice of salami, ate it together with a pickle, and took a drink of beer. “Seryozha!” she said, pointing at a plate of cake in the middle of the table.

The kid leaned forward, grabbed a piece of cake and stuffed in his mouth, still staring at Karl.

The woman and the fat kid began speaking in Russian while the man continued his monologue about their new life. Karl shut his ears. What pigs!, he thought. Like the money-grabbing Russians you see around Berlin’s markets. This was a bordel scene from Dostoevsky or a session of madness in Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov’s drinking room.

Carefully he placed his glass on the table, examined closely the orange-haired mother in the tight dress and the fat boy, turned toward their baggage near the door, and decided.

Slowly he stood up. The aliens fell silent and watched him. He walked to the door, opened it, and said in a low voice, “I want you to take your things, all your things, and get out of my house.”

“What? What …” began the man.

“Out! Get out of my house. Brother or no brother, get out of my house. Or I will call the police now.”

“But brother, the immigration papers! Our father signed for us. You are my brother. This is a family reunion. Fa-mi-ly re-un-i-on! Finally … all of us together.”

“My father is dead,” Karl said coldly. He felt he was behaving differently from the way Dieter would have. “I know nothing about yours.”

“You mean you know nothing about your father’s Russian family? My mother, Dasha, is your father’s Russian wife. His only legal wife! Your father, Dieter Wilhelm Strack, is my father. I am Dmitri Dieterovich Strack!”

Karl stared at him in disbelief.

“How?” he murmured. “When? He’s always been in Berlin.”

“At the end of the war they let him out of the POW camp … for some reason!” Dmitri said the last meaningfully, a sneer on his fat face. His tiny eyes almost disappeared among heavy eyebrows and his puffy cheeks glittered.

“The usual reasons, I’m sure,” he said, now almost gleefully. “He met my mother in a hospital … in Smolensk. She was a nurse. They married. And here I am with you in Berlin. Your half brother!”

“He died three days ago … an accident,” Karl said.

The usual reasons, the man had said. Yes, his father had boasted he’d been a secret Communist then. Was that the reason? But being a German Communist in Stalinist Russia was certainly no protection. In fact, it meant certain death. He was a German. A soldier. A prisoner of war. They didn’t just let them go. Unless … he hated to think it. Unless what? Unless Dieter was an informer? Was that what he meant? But he was only twenty-two when he went to war. His father, a traitor? Could he have become an informer in the POW camp? A spy against his own people?

“Dead? He’s dead? He sponsored our immigration. He gave this address. And you, Karl Friedrich Strack, as co-sponsor. Your signature is on the documents. You are a teacher, you earn well, and you generously agreed to guarantee for us.”

Karl felt he was going mad. What was happening couldn’t be happening in reality. This was pure folly. He was surrounded by unreality. His father’s folly. A forged signature. First abandoning one family, then the other. His mother had been right. She had sensed something was wrong. She always said he was falsch und trügerisch. A phony! Karl had thought it was just a spurned woman’s reaction. But it had been more. So that’s what Dieter meant when he said, “Things are never what they seem.”

And Helmut and Günther and Klaus? Had they never understood him? In all those years? And William too? But William was an American! Naïve. How could he grasp these German matters, things of the soul, concealed somewhere in our mysterious language and mystical culture. In a culture capable of Einstein and Marx and Hegel and Nazism and extermination technology? No, William could never grasp the nuances of Dieter’s world.

He looked over the shambles of his living room, shrugged and without a word walked downstairs to William’s apartment. Maybe they would understand and simply leave. His brother!

That evening William went upstairs to check. He reported party noises from the apartment, loud music and laughter and dancing. Karl decided to stay away.

In the following weeks Karl was to speak of the events of those days as historical landmarks. Post-war Europe was in shambles, he told his high school students in an attempt to explain the hopelessness in the literature of the early post-war period. Millions of uprooted people wandered around Europe aimlessly. Displaced persons—DPs. Homeless vagrants, stateless derelicts, the shipwrecks of a generation, victims of the failed promises of the century’s isms in which good was evil and evil, good. It was as if life were beginning again after a planetary holocaust. Though similar fates had struck Berliners of East and West, he realized—of fathers returning from the dead, of strange ancestors resurrected, of double and triple lives—it was as we think of terrible traffic accidents, great tragedies or even death itself. Such things happen to other people.

Early the next morning, after listening at the door to the foreign noises coming from inside his apartment, he sighed and started down the stairs for his school. If he wanted to he could tell his literature students some real Berlin stories. Oh, how innocent they were! How theoretical! How far removed from real life. He could tell them unbelievable stories that covered a century. But, he thought, the truth would be only more fiction to their ears. Better stick to Goethe.

Karl stepped out onto the sidewalk and bumped into a man running his finger down the names alongside the doorbells. He said he was looking for Karl Strack.

“Ich bin Strack,” Karl said. “And there’s no need to ring that bell.” Crazily, he was tempted to blab the wild story to the first stranger who came along.

The man was about Karl’s age. A journalist. His name was Horst Zimmerman.

“I read about your father’s accident,” he said, handing Karl his business card. “Please accept my condolences. It’s about him that I wanted to speak with you. Maybe it’s still too early.”

“I don’t mind at all,” Karl said, thinking that getting it all off his chest with a journalist would be more effective than seeing a shrink. “But in thirty minutes I have my first class. What about this afternoon?”

On the S-Bahn to Zehlendorf the name Zimmerman kept buzzing through his brain. He knew the name. It was well-known. Some sort of celebrity, he was certain. Hadn’t he seen a book by him or read a review of his work? Dieter too was quite a personality but hardly a VIP. What public interest did his passing create? Or, he asked himself over and over that day while speaking to his classes of Goethe and Dostoevsky, was Dieter really what he had pretended to be? Was he not more than he pretended? He was an actor in the play of his own life. One day, the true Berliner … or the ardent Socialist. The next the belated father’s role. His potential roles now seemed countless. His father’s words kept racing through his mind—things are never what they seem.

Horst Zimmerman was famous in his way. An investigative journalist at the Berliner Tagespost, he had made a career studying the obituaries. His interest was Dieter’s generation. The generation of his own father. He wanted to pinpoint the individuals of that generation and dissect them. He wanted the truth about actual people—he wanted to establish what individual persons had really done during the bad times.

His system was simple. In the years since reunification secret files of the former DDR had become public. Dry details in bureaucratic language about who did what in Germany arrived from the archives of the former East German secret police, the STASI.

It was in the order of things that from time to time the names of well-known public figures emerged … they quickly made the headlines. That was not for Zimmerman. It was the lesser known, the little men of the times, who excited his curiosity. Who were the thousands of agents in those secret lists, the as yet undiscovered informers, who had made the STASI so efficient? And so feared. But he was not a sheriff. He did not want to accuse them. Nor was he searching for notoriety. He just wanted to know what kind of people they were. And why they chose a path so different from other West Berliners? Were they Communist militants or just cynics, dedicated idealists or ambitious politicians, upright or unscrupulous, good or evil? Over and over in his reportages Zimmerman had posed the questions—were they traitors? And if so, traitors to what? Whom in fact did they betray?

He checked the names of a dying generation against available STASI lists … and then spoke with their surviving relatives. Astounding stories emerged. He was writing a new history of Berlin.

Potsdamer Strasse that afternoon looked and sounded like Turkey. Karl tried reading aloud the signs on the shops and the newspaper headlines at the newsstand. People passed him, entered the shops, bought the newspapers. They were all speaking Turkish. He understood nothing. Whole city districts were Turkish. As far as he could see up and down the avenue everything was Turkish. After Istanbul, Berlin must be the biggest Turkish city in the world.

Yet, he thought, either they were cut off from him or he from them. Or were they all isolated, new and old Berliners, alienated one from the other? Was multiethnicity only a meaningless sociological word? Was this the new world?”

In the Turkish coffee house the journalist asked what his father had done during the war. Karl told him about the Russians occupying his apartment—about his father’s Russian family.

“It’s not as incredible as you might think,” the journalist said. “Our soldiers were so young. Most soldiers are so young. But they were men too. For most of them Russians were not the enemy. They just wanted to live. How long was your father there … in Russia? Seven years? Eight years? That can be a lifetime at that age.”

“Do you think it’s that simple?” Karl said. “Dieter Strack was different. He was an idealist. Could he … could he have become an informer? Just to survive?”

“I think to live. It’s like you said, he wanted to live many lives. It’s not the same thing. Maybe he too regretted it later. On the other hand maybe he was more consistent than you imagined,” Zimmerman said.

Then he told Karl about Dieter Strack’s name in the STASI files—he was listed there as an informer in Germany.

Karl held his breath. Confirmation! He felt first disgust, then hate rise up from his guts. In a flash, years of happenings, pain, unknowing, abandonment, crossed his mind. A lifetime as an informer! While he had put on such airs. He told Zimmerman about Dieter’s friends who adored him, about his funeral, about his dedication to his city, about his social involvement, about his boasts of special contacts to go in and out of East Berlin, about his relationship with William. And how he abandoned his families and wore his silly tram driver’s uniform and preached about the rights of the people—

“Das Volk! Das Volk! Always what was best for das Volk.”

“Yes, but Karl, he was an unpaid informer. That changes things, doesn’t it? It’s written in his files—idealist. I’ve learned that intelligence people trusted idealists less. They never knew when they might change their minds. They preferred to pay them. That’s the way their world works.”

“So was he hero or scoundrel? For his sacred ideals maybe he was a hero. But for my mother, for his Russian family too, he will always be a scoundrel. How did his dedication help us? How did his dedication and commitment to the people help those he informed on?”

“I’ve encountered incredible behaviors in the most ordinary people … but the Dieter Strack you describe is not an ordinary person. He was capable of extraordinary acts. Some people last century committed the most hellish crimes. But sometimes even those same people performed superhuman acts of goodness … near godlike acts. Your father seems to have been one of those who believed everyone is right. He was no judge. Listening to these stories over the years I have come to suspect that transcendence happens often in the trenches.”

“But Dieter Strack was a traitor to himself and to his people,” Karl said.

“Was he? The question is, who were his own people? You told me he loved everybody the same. Maybe he did. Was that a crime? Or a sin? What was his real crime? That’s what we want to know.”

“I once thought his libido drove him from home … and his wife and child to Munich … and to do the things he did. But I was wrong. It was something incurable. Maybe his overweening pride. An excess of his German Stolz. After his first taste of pride there was no turning back. After turning informer, how could he ever be innocent again? I don’t know if his pride was the result of the life he lived or if the life he lived was a result of his self-assured pride. Did he become that way when he felt for the first time his power?”

“I’m a journalist, not a psychologist. But I know how hard it is to understand the real motives of others. And Karl, what do you think was his overall purpose?”

“I once thought it was simply to promote his city … Berlin. But then there was his ideal of the planetary community, as he called it. But it was even more than that. Maybe it was a war against evil. For him the ruins of Berlin were the incarnation of that evil. But all the time I had the sensation he didn’t really see evil when it stood before him.”

“Maybe he stood above particular evils.”

“I think so. Above good, too. He never felt inferior to the French as we Germans do, nor superior to the Slavs. His standard answer to life was simply that ‘man is man.’”

“What do you think he meant?”

“He asked me once—he looked perplexed when he said it as if he hoped someone would give him the answer—he asked which is best: life in a society where each is free to do as he likes and yet which ignores the welfare of the unfortunates? Or a society that feeds you and takes care of you and keeps you warm in the winter … but that demands total conformity?”

Karl continued to live downstairs with William while waiting for the bureaucracy to evict the Russian squatters from his apartment. The warranty to which Dieter had forged Karl’s name was serious business. Handwriting experts had mixed opinions. Immigration officials favored first Karl’s version, then the uprooted Russians. Police and immigration and housing officials were meanwhile disappointed when Dmitri signed a statement that he and his wife were Russians … had they been Russian Jews the decision in their favor would have been simpler. Yet because of Dmitri’s German father—not completely established because Dieter had left that point cloudy—they had preferences as German Russians seeking resettlement in the fatherland.

William had begun thinking of his return to New York. Afternoons, walking together over their favorite parts of the city, their thoughts returned to Dieter and his city. Some places they felt his presence strongly. In others he was predictably absent. His spirit accompanied them uneasily from Potsdamer Platz to Pariser Platz at the Brandenburg Gate, down Unter den Linden and through the Tiergarten to Schloss Park. More at ease up and down Friedrichstrasse, Dieter then delighted in the hike to the top of Prenzlauer Allee and back down Schönhauser. William noted Dieter’s miffed absence as they walked through the former West Berlin center out Kurfürstendamm. But he returned in all his pride to visit the old and new rail stations, the landmarks of the public transportation system that also fascinated William: Anhalter Bahnhof, Bahnhof am Zoo, Lehrter Bahnhof and the Ostbahnhof—formerly the station for Paris – Berlin – Moscow trains, now the terminus for ICE high speed trains—and Karl’s favorite, the Alexander Platz Station.

One warm day in May they were sitting at a sidewalk table at the Cafè Istanbul that Karl had begun frequenting since the interview with Zimmerman. He felt an inexplicable belonging among the people speaking a language of which he didn’t understand a word. He had begun thinking he would take a total immersion course in Turkish—he wanted to know who these people were.

“Spring is finally here,” William said, “and the mosquitoes will soon return.”

“William, how many times do I have to tell that there are no Mücken in Berlin?” Karl chuckled, aware that his friend could go on for hours about the mosquito threat. The summer before he had actually used a mosquito net, right in Berlin.

“That’s a fiction … propaganda spread by tourism and city PR people. What do you think I do with all my sprays and ointments.”

“Well, I’ve never seen a mosquito in Berlin.”

“You’re like your father in that. He bragged there were no mosquitoes west of the Oder River. He claimed they were as big as birds in Russia.”

“He exaggerated a bit in that.”

Karl enjoyed speaking about his father, about his quirks and strange convictions, more than he had speaking with him in life. But he had concluded that on a moral level there was no restoration for Dieter. No rehabilitation. His life was over. Finished. Dieter was wrong. And Zimmerman was wrong, too. For there was a basic human element common to all. An ethical instinct. A limit you didn’t surpass. Dieter had. Though his father had seemed to live in accordance with some self-imposed monastic rule, he had in reality lived a carefree life—‘capering and cavorting outside the walls of the City’.

What buffoonery, his life!

His determination to live diverse lives! Who did he think he was?

And poor William, his spiritual brother. Karl had thought of him as Dieter’s true son.

Some days later Zimmerman telephoned to tell Karl he shouldn’t worry—the majority of the names in STASI lists resulted from denunciations by others. Everybody in those years, he said, was denouncing everybody.

Karl sighed and whispered to himself that for Zimmerman, too, it was a case of ‘if everyone was guilty then no one was guilty’. Precisely what Dieter had opposed.

Karl felt Dieter’s and his own severity rise up in his belly. The journalist’s escape clause was too easy. Yet he knew he would never condemn his father.

Dieter’s planetary community would never work. It was too intellectual, it always went wrong, some people would always believe they were better than others … and that conviction led to Auschwitz.

Karl and William agreed that Dieter’s unexpected truth was that ‘man is man’. Yet neither of them understood how he had acquired such humanism in his generation of ideologies when it was considered good to kill your enemies.

Dieter Wilhelm Strack, his son Karl said, was a son of Berlin.

And also a victim of his epoch.

![]()

Our Senior Editor based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

Our Senior Editor based in Rome, serves—inter alia—as our European correspondent. A veteran journalist and essayist on a broad palette of topics from culture to history and politics, he is also the author of the Europe Trilogy, celebrated spy thrillers whose latest volume, Time of Exile, was recently published by Punto Press.

=SUBSCRIBE TODAY! NOTHING TO LOSE, EVERYTHING TO GAIN.=

free • safe • invaluable